What I’m noticing these days is the quality of attention that is invited (or demanded) by any given performance. Other than that very subjective standard, this list is, of course, limited by what I’ve actually been able to see this year.

Ailey’s 60th Knocks It Out of the Park

The company has stretched in many directions under Robert Battle while still preserving its heritage. During this 60th-anniversary season, they struck it rich with world premieres from Rennie Harris and Jessica Lang and a company premiere of Wayne McGregor. Ronald K. Brown made his seventh luscious ballet for the company, and the Robert Battle evening showed what how powerful Battle is as a choreographer—and witty too.

Rennie Harris’ Lazarus rises from utter despair to infectious joy. Hints of lynchings are rendered subtly, eliciting feelings that linger. The vocabulary seems to draw from a wide range of black vernacular—I thought I saw more gumboot than hip hop.

Lazarus by Rennie Harris, Daniel Harder in center, photo Paul Kolnik

In Jessica Lange’s EN, a circle is an eclipse, a moon, a pendulum, a gathering point, and a symbol of life cycles. Jacub Ciupinsky’s percussive score has unexpected spare moments that allow reflection, time for breathing and listening amidst the symphonic choreography.

Jessica Lang’s EN, photo Paul Kolnik

Wayne McGregor’s Kairos: If you could picture watching human fireflies through a musical staff, that’s the opening. This is a softer look for McGregor. The women are strong and the men are affectionate with each other. The choreographic flow is entirely engaging.

Kairos by Wayne McGregor, photo Paul Kolnik

More than that, this anniversary gave us a chance to reflect on the long-term effects of Ailey’s success. The company tours extensively, spreading seeds of inspiration all over the world. (At the recent Dance Magazine Awards, both Ronald K. Brown and Crystal Pite told stirring stories of how Ailey was the spark that made them want to dance.) The company continues to cultivate fantastic dancers, and the audiences are more racially integrated than at any other dance event. These are huge, ongoing gifts. Thank you.

Jane Comfort: Still Telling It Like It Is

The 40th-anniversary program at La MaMa showed that she’s been dealing with issues of race and gender—with directness and humor—for decades. A vibrant cast performed superb selections from her oeuvre, with co-direction by Leslie Cuyjet and Sean Donovan. Bravo for the artistic power of a woman of a certain age!

Magic Realism from France

Compagnie Accrorap in The Roots, choreographed by Kader Attou, at the Joyce: We’re in a funny nightmare where the timing is uncanny and everything is askew. The chair and sofa are tilted, the lamp twirls of its own accord. The choreography is sly, spectacular, sullen, sneaky, allowing the male cast to spin out hip hop and tap dancing feats in a surreal world.

Accrorap in The Roots, photo ©João Garcia

Most Drastic Storytelling

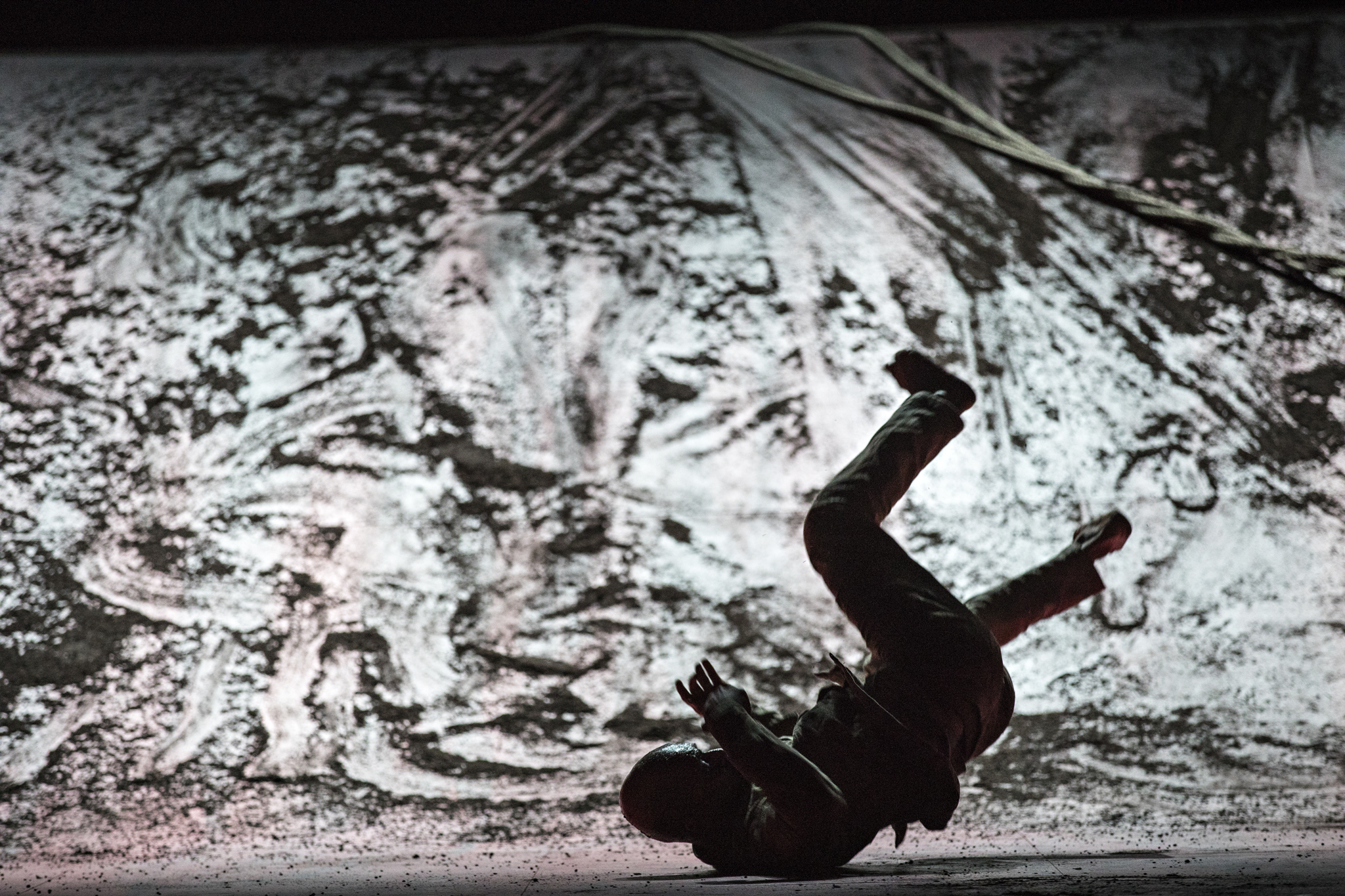

Akram Khan’s Xenos, at the White Light Festival: The terror of fighting as a colonial soldier, rendered with poetic swiftness. Khan’s final full-length solo (say it’s not true!), with the help of lighting, set design, story, and music, imprints on the memory. In a program note, he asks, “How can we, as humans, have such ability to create extraordinary and beautiful things from our imagination, and have, equally, our immense ability to create and commit violence and horrors beyond our imagination.”

Akram Khan in Xenos, photo Jean-Louis Fernandez

Best Religious/Military mix

Ka’et Dance Ensemble in Heroes, choreographed by Ronen Izhaki, at the Marlene Meyerson JCC Manhattan. The four male dancers are Israeli yeshiva teachers and students who have served in the Israeli army. Splicing between interior moves and madcap aggression, the rough-edged Heroes shows the tug between the spiritual man and the fighting man. Their timing with each other is scarily precise, which makes the blessings, where one’s head seems to melt beneath another’s hands, so touching.

Most Poetic Minimalism

Latitude, by Dana Reitz, presented by Lumberyard at The Kitchen, is an exquisite distillation of three women entering into swaths of light and motion. Its painterly quality lets your eye rest on the images. The careful placement of sticks, the dancers’ patience in waiting for each other, and how they steer us to see specific light and shadows, create an oasis. During one duet, the soft humming made it feel celestial.

Bottle-hurling Sport Dance

Twelve by Jorge Crecis gave Acosta Danza’s debut at NY City Center an exhilarating closer. Hurling bottles of water around in game-like formations, sometimes jumping up to catch a bottle in the nick of time, the 12 (or was it 13?) men and women had the astonishing coordination of jugglers or acrobats. It’s a new form of sport/dance that was terrifically exciting. For the final scene, they all freed themselves into gaga-esque buggying that stole our hearts.

Acosta Danza in Twelve, photo Johan Persson

Art as Healing

Meredith Monk’s Cellular Songs at BAM is mostly voice and film with bursts of dancing here and there. At 70+ she’s only slightly brittle, but still has the ability to project spiritual ecstasy. While singing the song “I’m a happy woman,” she radiates an intelligent happiness, as well as sorrow, anger, and fatigue. The film component gives the illusion of hands coming from all dimensions, making you feel you are held by the hands of a goddess. Only Meredith Monk can make peacefulness and cooperation into a major theatrical event.

Pointe Shoes as Percussive Instruments

Michelle Dorrance’s pièce d’occasion, Praedicere, for American Ballet Theatre’s Spring Gala, got the ABT dancers to concentrate completely on rhythm. This burst of purposeful sound making—pointe shoes jabbing the floor—had more impact than Dorrance’s more picturesque premiere later in the season. Praedicere (does it mean “before language”?) deserves a second run; it’s a refreshing break from the lavish, European-based ancient ballets that are produced by ABT.

Fabulously Funny Duos, Redux and New

David Dorfman and Dan Froot were at it again, with their physical comedy that is both hilarious and touching. This time, at the Jews and Jewishness in the Dance World conference at Arizona State University, they produced So You Think You Can Schmooze: Post-Future Jewishness in a Dancing World, where the conceit was that it’s the year 2030 and they are the grandsons of entertainers named named David Dorfman and Dan Froot. This one idea triggered a cascade of jokes, both verbal and physical, ending in a waltz around the stage for everyone.

Dancenoise’s Lock ’Em Up at NY Live Arts: Lucy Sexton and Annie Iobst are as bawdy, transgressive, and chuckle-inducing as they were 35 years ago. With a cast of seven ready-for-anything helpers, they poked at issues like fracking and gun violence. Why is all that bright red blood smeared on their slips liberating? Why are they so damn comfortable, even now, in their 60s, sitting around chatting in the nude? I don’t know, but I am glad they exist and persist.

Lock ‘Em Up by Dancenoise, photo Ian Douglas

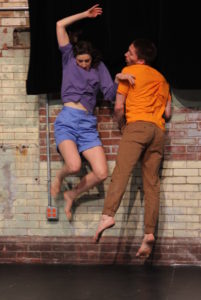

Show No Show, photo Hallie Martenson

Fab Funny NEW Duo

Show No Show at The Flea Theater: Gabrielle Revlock, from Philly, and Aleksandr Frolov from Russia, make a giddy cross-cultural pair. (You know that Russians never smile, right?) Discovering new and delightful ways to torment each other, they splice awkward not-quite-seductive encounters with scrappy movement jokes.

Orchestrated Chaos

Boris Charmatz’s 10,000 Gestures at NYU Skirball made me smile right away. Johanna-Elisa Lemke’s opening solo was like Rainer’s Trio A on speed amplified 20 times. Later I saw a sliver of the real Trio A done in an upstage corner, by Frank Willens, while 19 other crazy things were going on. I understand the objection some had to the in-the-face tromping over the audience. But at that moment, I was digging the brazenness of them clambering over the heads and bodies of us spectators. (Photo below by Tristram Kenton.)

Dipping Ballet into Black Culture

The Runaway, Kyle Abraham’s first piece for a ballet company, used music by Kanye West, Jay-Z and Nico Muhly to superimpose Abraham’s hip-hop–influenced ripples onto the bodies of New York City Ballet dancers. The Runaway cracked open the pristine whiteness of ballet to receive a bit of the black culture that is all around us. It was remarkable how well it all fit together.

The Poetry of Protest

Hadar Ahuvia performed an excerpt of Joy Vey at the Jewishness conference. She was skimming the earth with folk dance shapes turned liquid. On recording, we heard her voice speaking a poem… “and maybe we didn’t shoot at them and maybe there is a people as righteous as us.” It slowly dawns on us that she is dancing to unwind the nightmare on the other side of the border with Palestine, to unwind all she has learned as an Israeli-American. (Disclosure: I co-curated the concert she was in.)

Hadar Ahuvia in Joy Vey

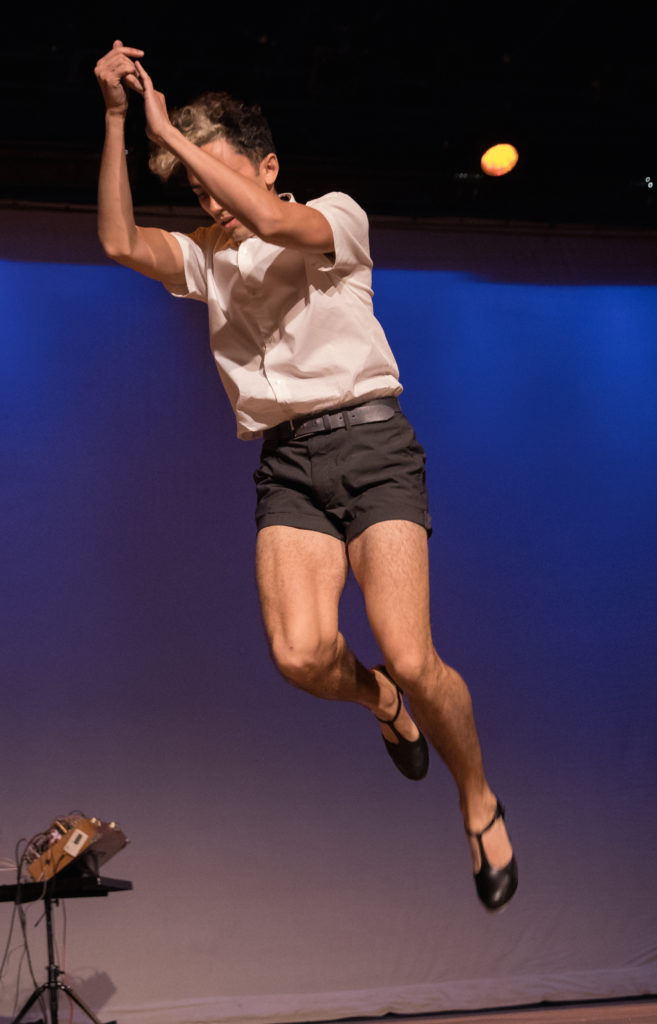

Caleb Teicher in Great Heights, photo Amanda Centile

Caleb Teicher Hits It Twice

At Tap City’s “Rhythm in Motion” program at Symphony Space, Caleb Teicher went from morose to clownish to draggish to poignant in his Great Heights solo. Wearing high heeled tap shoes and short shorts that reveal gorgeously muscled legs (costume by Marion Talan), he tapped up a storm on top of a narrow bar stool. Then, in Fall for Dance, he premiered Bzzz, again blasting us awake, this time with a kind of call and response with his group.

Taking the Improv Challenge

Timothy Edwards, photo Yi-Chun Wu

Timothy Edwards improvised split-second changes of intersecting, intercepting deep gesture for Nicole Wolcott’s This Man at Dance Now at Joe’s Pub. Emotionally exhausting and exhilarating, the solo is billed as a collaboration between Wolcott and Edwards.

Michelle Boulé’s quicksilver wanderings in Bebe Miller’s In a Rhythm at NY Live Arts captivated me. Her energy follows a naturally unpredictable path that is pretty exciting.

Switch, by Rashaun Mitchell + Silas Riener, in collaboration with six improv-savvy dancers, devised a score that was mysterious in its portions of observing and doing, orneriness and wit. In its wayward impetuousness, it reminded me of the legendary ’70s improvisation collective Grand Union. Performed as part of Quadrille, Lar Lubovitch’s reconfiguration of the space at the Joyce.

Reconstructions and Revivals

Merce Cunningham’s Signals (1970), part of Stephen Petronio’s Bloodlines series at the Joyce. Serious, spunky, playful. Sustained lines, solid balances, dancers holding up fingers to signal the choice of sequence. The Merce character is a magician who emits odd groans.

Molissa Fenley’s Mix (1979) at Danspace, in which four dancers clap and stomp their way into a manic euphoria of driving rhythms and geometric patterns. The street-wear costumes help to make it feel like today.

Kei Takei, Solo from Light, Part 8 (1974) at Lumberyard: She’s a cheerful madwoman determined to tie herself into knots. And you cannot look away as she does the inevitable.

Ishmael Houston-Jones, THEM (1985) at P.S. New York: slippery entanglements, self-punishing escapades…danger at every caress. Can you trust the person you’re attracted to?

David Gordon’s The Matter, begun at Oberlin College in 1972 as part of a Grand Union residency, has gone through various versions. This one, part of MoMA’s “Judson Dance Theater: The Work Is Never Done,” is layered with start-and-stop actions, talking, and films, giving a sense of overlapping time lapping up on the shore. Wally Cardona and Karen Graham re-enacted the love-and-loss duet of David Gordon and Valda Setterfield, giving just the right touch of melancholy within precision.

Best Performers

Marta Ortega of Acosta Danza in Mermaid by Sidi Larbi Cherkaoui at City Center: Liquid, as though she were both the mermaid and the water, she more than held her own beside the still charismatic Carlos Acosta.

Marta Ortega with Carlos Acosta in Mermaid, photo Johan Persson

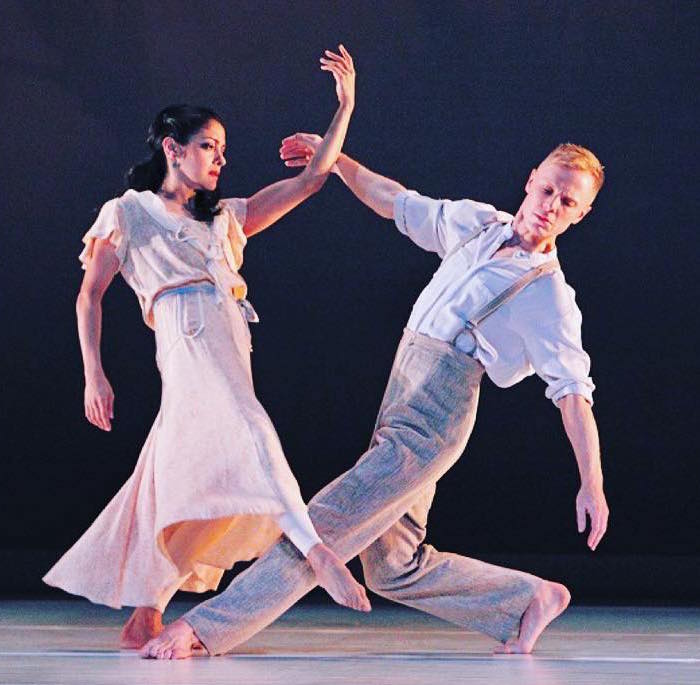

Michael Trusnovec and Parisa Khobdeh in Paul Taylor’s Eventide: a controlled slowness expressing infinite tenderness. (Trusnovec just received a well deserved Dance Magazine Award.)

Parisa Khobdeh and Michael Trusnovec in Taylor’s Eventide, ph Paul B. Goode

Taylor Stanley, who is great in everything, ran away with Kyle Abraham’s Runaway, his spine swerving between upright ballet positions and the pelvic swagger of hip hop.

As Isadora Duncan, Sara Mearns danced with dignity, arms floating, body swirling. Staged by Isadora authority Lori Belilove, this version appeared on Paul Taylor’s American Modern Dance as well as in Fall for Dance. Even if Isadora was earthly, Mearns was heavenly.

Rakeem Hardy was transfixing as the man climbing a mountain in (C)arbon by Andrea Miller and Gallim, at the Met Breuer. Totally exposed, he committed to every ounce of the trembling, staggering choreography.

Cailtin Scranton as Ursula, photo Andrew Jordan

Caitlin Scranton, luminous, mysterious…austerious, if you will, as Ursula in an excerpt of Christopher Williams’ Ursula and the 11,000 Virgins at Cathy Weis Project’s Sundays on Broadway. Her lethal-looking claws hovered near her tender, exposed flesh.

Megan Wright of the Stephen Petronio Dance Company, in Steve Paxton’s Goldberg Variations (1986–92) at MoMA’s Judson series. Sudden, quirky dynamics emanating from the center of the body. She applied whiteface, mimicking a mime in the sense of invisible forces pulling and pushing her, surprising her. She was led by the force of her body reacting to Glenn Gould’s recording of Bach.

Megan Wright in Paxton’s Goldberg Variations, photo Paula Court

Three Crucial Exhibits

Arthur Mitchell with Allegra Kent in Balachine’s Agon, 1962, photo Fritz Peyer

The Arthur Mitchell exhibit, Harlem’s Ballet Trailblazer, at Columbia University gave space to the many roles of the groundbreaking dancer/activist/leader. He broke the color bar at New York City Ballet and he started Dance Theatre of Harlem, which met with wildly enthusiastic audiences all over the world. The exhibit opened and closed last winter, just in time for Mr. Mitchell to enjoy it at the end of his life. The extensive online component, with interviews, photos and video clips, is hugely educational and inspiring.

The Museum of Modern Art’s current exhibit, Judson Dance Theater: The Work Is Never Done, covers a wide swath of the milieu surrounding the break from modern to postmodern dance. The hundreds of items include rare films of work by Lucinda Childs, Steve Paxton, Yvonne Rainer, Robert Rauschenberg, and Elaine Summers. Currently the exhibit is showing a slew of archival videos of Trisha Brown.

Concert #13, A Collaborative Event, Judson Dance Theater, 1963, photo Peter Moore

In conjunction with New York City Ballet’s Robbins centennial, The NY Public Library for the Performing Arts has mounted Voice of My City: Jerome Robbins and New York. It reveals this monumental choreographer as a sensitive observer of life, a gatherer of material from the streets of New York. There are video and film clips of West Side Story and Dances at a Gathering that I never tire of. The surprise is Robbin’s overflowing creativity on the page—in writing and drawing. Luckily, the exhibit is up until March 30.

Most un-heralded racial reversal on Broadway

King Kong falls in love with . . . not a blond white woman but a young, street-wise black woman, played with great moxie by Christiani Pitts. Directed and choreographed by Drew McOnie. Throughout movie history, it’s always a white woman who is the tantalizing object of adoration for men and animals. They roar for the pinnacle of sexual privilege. To cast the character of Ann Darrow as a person of color changes our assumptions about cultural desire. And Pitts has the charisma to pull it off.

Most Heartening News

Kyle Abraham decided that he will only agree to have his work performed on a shared program if a woman’s choreography is also on that program. Kudos to a male choreographer for having the consciousness to advocate for women in dance!

Most Disheartening News

Hearing that Amar Ramasar, one of the most humane dancers on the ballet stage, allegedly participated in a mindless activity that was demeaning to women.

In Anticipation

We await two announcements that could change the dance world: The appointments for new artistic director of New York City Ballet and new chief critic of The New York Times. In a field where women are routinely passed over for leadership positions, I’m hoping…

Good Reads

It was a good year for dance books, as you can see from my list of “11 Most Notable Dance Books of 2018.”

Featured Leave a comment

Ballet for Life: A Pictorial Memoir

Ballet for Life: A Pictorial Memoir Ballet Matters: A Cultural Memoir of Ballet Dreams and Empowering Realities

Ballet Matters: A Cultural Memoir of Ballet Dreams and Empowering Realities

William Forsythe: Choreographic Objects

William Forsythe: Choreographic Objects Judson Dance Theater: The Work Is Never Done

Judson Dance Theater: The Work Is Never Done

Honest Bodies: Revolutionary Modernism in the Dances of Anna Sokolow

Honest Bodies: Revolutionary Modernism in the Dances of Anna Sokolow Jerome Robbins: A Life in Dance

Jerome Robbins: A Life in Dance Gravity

Gravity The Next Wave Festival

The Next Wave Festival