In light of this being the 50th-anniversary year of Twyla Tharp’s choreographic life, we asked Sara Rudner, who was deeply involved in Tharp’s early dancing-making, to come to NYU Tisch Dance (where I am an adjunct) to talk about working with her. Rudner, who is now the director of dance at Sarah Lawrence College, imbued her dancing with light and depth and helped create the Tharp style. Rudner’s talk, which focused on Tharp’s work but also touched on her own choreography, took place in one of the NYU Tisch Dance studios on September 25, 2015. Luckily, one of our sharp grad students, Donald Shorter, turned on the voice memo of his cell phone and recorded the event. I transcribed his recording and edited the interview slightly, then got Sara’s input to clarify some sections. To learn more, go to the Tharp website.

Wendy: How did you first start working with Twyla?

Sara: My friend Margy Jenkins was working with her. We were neighbors on Broome Street. Twyla was doing a show and she needed another dancer, and Margy said, “I know someone.” And Twyla wanted to see who I was before she didn’t pay me—before she didn’t pay me. [laughter] No one was paying anybody, there was no money, but I did receive $50 for the first performance of Re-Moves.

Wendy: The NEA [National Endowment for the Arts] didn’t start till later in the 60s.

Sara: There was no New York State Council on the Arts. Anyway, so Margy took Twyla to see a performance I was doing at Judson Hall. Barbara Gardner had done a piece and someone got injured and I stepped in and I learned the piece. Margy said that Twyla came in [to see me dance] and stayed for a few minutes and said, “She’ll do.” [laughter] That was the beginning.

Wendy: And boy did she do! Sara defined Twyla’s work for 20 years.

Sara: We came from very different backgrounds—I was a New York City kid, born and raised in Brooklyn. I had no art training. I ran around and swam.

Wendy: And you didn’t do ballet training.

Sara: I had a little bit of baby ballet. I knew what that was, and then nothing. But our energy was very similar. So one of the first times we met [in the studio], I saw her rubbing her hands, saying Ah, you’ve got a lot of energy.

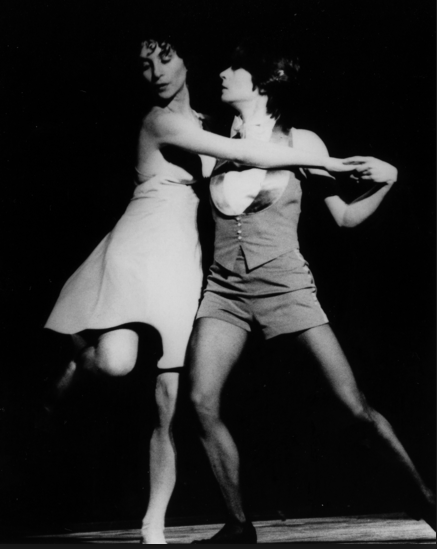

Sara Rudner and Twyla Tharp in “The Bix Pieces” (1972), photo by Tony Russell

Wendy: She was probably thinking, Ooh what I can do with this girl!

Sara: I was really almost a blank slate. The first time Margy told me that she was studying with Merce Cunningham, I said, “Who’s she?” I had no idea. I had a degree in Russian studies from Barnard College, I was 20 years old and I knew nothing. So it was a perfect opportunity because I was a blank slate and had a lot of energy. I’d been a swimmer and a runner, so I was strong and well coordinated.

Wendy: That’s so interesting because now, one of the people she likes is John Selya, who was a surfer. Twyla always liked someone who looks like a person onstage rather than a dancer with this kind of I’m-dancing-for-the-balcony-seats projection. And you were definitely that person.

Sara: In the beginning experimentations she chose to work with Margy Jenkins, who’s a statuesque woman, and then with me and then with herself. So she was not into the cookie-cutter thing, she was experimenting with the kinds of people. When I say experiment, I mean she experimented like crazy. We did all sorts of things that most people if they look at them now they would say, That’s not dance. The first thing I ever did with Twyla was with a stopwatch; it was at Judson Church. My part was [gets up and walks a straight line, the long side of a rectangle]. Then I got to a corner and I returned to where I began to give the stopwatch to Margy, maybe Twyla, and she walked the diagonal; and Twyla, or maybe Margy, walked the short side of the rectangle.

Wendy: Was that Re-Moves?

Sara: Yes, Re-Moves, 1966, was task-based. Twyla was looking at stuff from the bottom up. She had done all this dancing; she had done a lot of ballet. There are pictures of her in a tutu, wearing a tiara.

Wendy: Do you think she was influenced by the other stuff going on at Judson? Yvonne Rainer and Trisha Brown and Lucinda Childs were also very task-based.

Sara: Yes, task based. She was also very influenced by the minimalist painters.

Wendy: Of which her husband, Robert Huot, was one.

Sara: Yes. Those early pieces had props, objects, were spatially very structural. They were circles, squares, oblongs. They [minimalist painters, sculptors and dancers] were all hanging out together. Twyla was in that group of people who went to Max’s Kansas City and drank a lot and ate ice cream. That’s what I remember about Max’s Kansas City is the ice cream sundaes Sundays. But eventually—Twyla’s a dancer. She loved movement; she loved complicated things, she loved a great physical challenge. And the physical challenges in those early pieces were really intense. In the same piece, Re-Moves, there’s a balcony at Judson and she hung a ladder, a rope ladder down, and I climbed down the rope ladder backwards. I was wearing black leotard and tights—we all were—and a white felt hat.

Wendy: Yeah, you looked like nuns in the photos.

Sara: The hat was a triangle, and the tip was in the middle of the forehead.

Wendy: And Robert Huot probably designed it.

Sara: He designed it, yeah. The thing she asked me to do was to walk backwards on relevé after coming off the ladder and make zig-zag patterns. So if the ladder was there, the pattern was [demonstrates in the space] zig-zag zig-zag all the way down till I ended on the floor. The entire time I had to slowly lower my arms and head, flex my spine, bend my knees until I was lying supine on the floor. It took about 10 minutes.

Wendy: Were there other people doing other things, or that was it?

Sara: I was supposed to give a cue in performance but I went so slowly that the cue I was supposed to give was late. Technically I was not so great, and the task took a lot of control and concentration. It might have been easier if I had gone faster.

Wendy: Most of these pieces were in silence, right? Was there music?

Sara: No but she would choreograph to music. We would dance to Beethoven, Mozart. We didn’t perform to music until Three Page Sonata for Four (1967), with music by Charles Ives. She was extremely musical, even to the point of translating musical scores to lines. She would set up a straight line, I followed the rhythm of one musical line, she the other. We would take the rhythms and go back and forth on the lines. Something like that [demonstrating]. It never looked like music; it was just us translating those musical phrases.

In Judson gym, rehearsing for “Three Page Sonata for Four” (1967); left to right: Theresa Dickinson, Rudner, Tharp, Margery Tupling; photo by Robert Propper.

Wendy: In her later work, one of the things she’s known for is her range of music—classical, rock, jazz.

Sara: Wide ranging, big appetite for dance art. Huge. Huge energy; questioning all the time. Very intense intellect. She brought extreme passion into our work together. She was also a monster mover. This woman …she was unbelievable,…watching her dance was really extraordinary.

Wendy: My eye always went to Sara, because Sara, in addition to being an incredible mover, has a kind of sweetness. [To Sara:] Your whole body was in every movement. Whereas Twyla gave off a different energy like, “I’m getting through this.” It was more belligerent.

Sara: She was fierce. She was hyper-mobile in her joints. She had strong muscles so could keep all that together and she had great power and reach. She also had a personality. What happened was, because we had a range of personalities and physicalities, it gave the work a more everyday look, less like a corps de ballet.

Wendy: Rose Marie Wright was six feet tall. She told me in one interview, “When I was dancing in Pennsylvania Ballet, they didn’t know what to do with me. They just couldn’t cast me in anything.”

Sara: In toe shoes, she’s like 6 foot 3 inches.

Wendy: And she said, “When I got to Twyla, Twyla knew what to do with me.” And Twyla put her to work. It was the three of them: Twyla, Sara and Rose were like the three goddesses for years.

Sara: We did a lot of work together, a lot of hours. What I learned from Twyla besides the amazing experiences she gave me, was how to work, how to be in a studio and just focus on what I was doing. Let’s do it again. Let’s do it again. Oh, maybe we should do it again. One more time—17 more times later—one more time. Let’s do it one more time.

Wendy: Because the work was so intricate.

Sara: It was very intricate, and to put that into your muscle memory so that you could then be fairly accurate. There were pieces I never did correctly. I never did it the way it was written. We were a team so we could pick up and be where we needed to be.

Wendy: But she also wanted a little freedom in there, didn’t she?

Sara: Not in The Fugue.

Wendy: How much movement did you contribute? The Fugue (1970) had certain variations; did you make your own variations?

Sara: No, that was a set piece. The time we started doing things individually was in Medley which was created before The Fugue. Medley was danced outdoors in 1969 on the great lawn and at American Dance Festival when it was in New London, CT, and this was a real experiment for her. We were all working down in Kermit Love’s studio on Great Jones Street. There was a studio and she’d take us in one by one and she would do something, and the others didn’t know what she was doing in there. She would say, Don’t tell the others what we did. She had made some phrases and then she just did them and said, What do you remember? So we each came up with something different. She started working more improvisationally with us. She also worked with each of us separately in different ways. She wrote down words that were prompts, and then she’d string whatever we did together. That’s the first piece she didn’t dance in. So that piece led me to be an individual dancer.

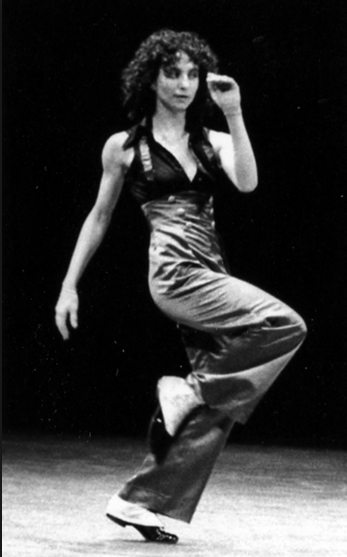

Rehearsing at the Metropolitan Museum for “Dancing in the Streets of London and Paris, continued in Stockholm, and Sometimes Madrid,” 1970. Rudner at left with braid.

Wendy: How were you earning a living? You were spending hours and hours in the studio with Twyla, not getting paid very much. What else were you doing?

Sara: I worked for a slumlord in his office. In 1965–66, I worked for the Free Southern Theater. It was an integrated group of actors who went down south and blew everybody’s mind. And then I started working for Merce Cunningham, in Merce’s office at Brooklyn Academy of Music. I did clerical work; I typed. (I learned typing in my high school.) Rose babysat. Theresa Dickinson did administrative work for arts organizations and proofreading for science textbooks. Margery Tupling had her own source of money. I could work for half a day; I could leave work at noon and take a class, then go to rehearsal.

Wendy: When did you start choreographing yourself?

Sara: The first thing I did was the program with Douglas [Dunn] in 1971 at Laura Dean’s place. I started with Twyla 65-66 and then I stayed with her until ’74. In the early ’70s I started working with you guys [Wendy Rogers, Risa Jaroslow and Wendy Perron] and I started doing other things on my own. Twyla was amazing because she insisted at some point that the dancers she was working with get paid 52 weeks a year. We didn’t have a lot of money. Part of my curiosity about being in dance was Let’s take responsibility for your artistic ideas: Rehearsals, going on tour, the bus, the airplane, whatever. I wanted to learn more about the business of making dances, putting them on, working with dancers. So in 1974 I said I think I need to do other things,, and she said, Are you gonna have a baby? [laughter] What could you possibly wanna do…and she was right in many ways. (I did have a baby many years later.) But I was hanging out with other dancers, and people were talking about what they were doing. I was 30 years old and I was thinking, Yah maybe I should find out about other things. So I went off and made a couple solos, and danced with Wendy P. and Risa and Wendy Rogers, we did marathon dances. Five hours at St. Mark’s Church.

Wendy: You had a whole philosophy about that, so talk about that.

Sara: As far as I was concerned, dancing happened whether someone watched you or not. Dancing was always going on. So the idea behind this was, we were dancers and this is what dancers do – dance. I had initially asked for seven hours, but Barbara Dilley [director of Danspace at the time] and the people at Danspace, said six, five maybe. So we bargained. But the idea was, we’re just gonna keep on dancing. You [the audience] can come and go whenever you want. We started at 5:00 pm and we ended at 10 pm. We worked our way up methodically. We created all this basic material that we all danced together, the phrases we made together then we set up improvisations. “Brain Damage,” one of the sections, was the hardest concept to realize.

Wendy: I can’t forget “Brain Damage.”

Sara: “Brain Damage” was one pattern in the arms and another pattern in the legs, it was like a five against a seven, so nothing fit together.

Wendy: And there was running in circles, and slightly different versions of it, which I extricated myself from because I didn’t have the stamina to run. [This clip from “Running” section, as performed in 1975 at Oberlin (without Sara), is mostly with Wendy Rogers and Risa Jaroslow.]

Sara: We were running around, and did some improvisation, we didn’t have music.

Wendy: Didn’t we have a fan making noise?

Sara: Yes, we had a backdrop, which was painted with floral designs by visual artist Robert Kushner; it was hung across the altar at St. Mark’s. At that point, St. Marks’ Church had fixed pews, a big wooden cross, and a red linoleum floor. Bob hung curtains in panels, and he had fans that blew these panels. When we weren’t dancing we were hiding behind the panels.

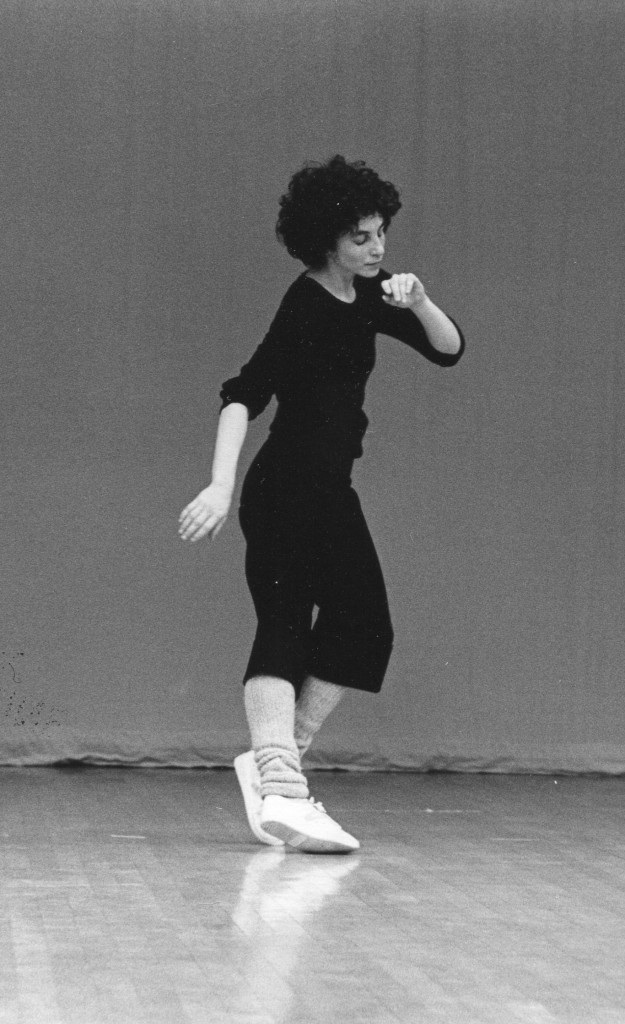

Rudner in her own solo, “33 Dances on her 33rd Birthday,” 1977, photo by Nathaniel Tileston

Wendy: There were just four of us.

Sara: Just four of us for five hours. It was intense. And my mother asked why we didn’t shave under our arms. [laughter] We were making a statement. “It’s not nice,” she said. But she came and watched. And people did come and go.

Wendy: Carolyn Brown stayed the whole five hours, and so did Kenneth King. The whole thing was to have dance be a continuum [to the students] not like a thing that had a beginning, middle, and end. You guys read the Merce Cunningham essay “The Impermanent Art.” Very much along those lines: Dancing is as impermanent as breathing.

Sara: It’s just what we do. [to the students] I know you guys have the same experience. You come here in the morning and you work all day. So we just put it all together. I couldn’t get to do that kind of thing with Twyla because her aesthetic was really to be in theaters and make those pieces and that’s what she wanted to do.

Wendy: And she changed more towards the theatrical. The things you were describing with the stopwatch, in the beginning…

Sara: That was open spaces. That was very simple. And then we had our hair done, and put on beautiful costumes.

Wendy: The haircutting was a big deal. In 1972 all dancers, whether ballet or modern, had their hair in a bun. And all of a sudden, Twyla and her two main dancers had their hair cut at Sassoon and they were stylish-looking. And then everyone went, Why do we have to have our hair in a bun? For women in downtown New York, it was a landmark influence; we started wearing our hair in more the way we might want to rather than like ballet girls. Onstage it made it even more that thing of They’re people rather than “dancers.” It made the performers closer to the audience somehow.

Sara: They could identify more. Especially during the ’70s, in hippie land, and feminist land. And we all were different. Twyla had a blunt bowl cut. Rose had longer hair, shaped, and my hair was layered into curls.

Wendy: And this was during the feminist time, and it had to do with what Twyla was doing onstage because her women were very athletic, they could do a lot physically. The first company was just women, and they were so strong and they didn’t have to relate to a man. It’s the way Martha Graham’s company started too: it was all women at first.

Sara: And then things progressed. Wendy and I were talking about the dichotomies of Twyla’s work: the Apollonian and the Dionysian. There were these very methodical pieces, and then there was a piece called Jam. Jam was premiered at Barnard College in 1967 and we were just throwing fits. We wore thick plastic costumes, full body suits and if you just blew on them, they made a horrible noise. You know those lights when you’re driving and you need flashers because your car is breaking down? One side is a spotlight and the other side is the flasher. So these spotlights were in our faces and we were in these noisy costumes. We had these fits and we would shake. Twyla choreographed it to James Brown. We would stop while Margy was doing something very serene. It was really pretty wild.

Wendy: But that sounds like Deuce Coupe. She had the ballet person being serene and then all you guys were doing crazy stuff. [To the students] Deuce Coupe was in 1973, and it’s when she brought her own dancers to the Joffrey’s ballet dancers. The music was the Beach Boys, so that was already a kind of sacrilege. In the first version, what she had for a set was about five kids who were already doing graffiti on subways. There was a scroll upstage, and they would come in spraying the graffiti, and the scroll would go up and they’d spray graffiti on the new stretch of paper. So she had two kinds of dancers, Beach Boys music, and the graffiti kids, and the whole thing made a statement of smashing high art and popular art together.

Sara: And this tour [Tharp’s 50th-anniversary tour] is Bach and Yowzie.

Wendy: Apollonian and Dionysian, two different halves.

Sara: She started that with Bad Smells and Sinatra Songs (both 1982). Bad Smells was everybody wearing rags. It was an intense dance. That was the first time she used a big screen. SONY had this big screen and Tom Rawe was filming it while it was going on. No one was using video that way. She was pushing the envelope early and hard.

Wendy: That takes a lot of courage. Where do you think she got that courage from, or how did that manifest in your work with her?

Sara: When we got in the studio we just worked. Twyla never came in and started talking about “It was a horrible review, I don’t know what I’m doing, I’m feeling lousy today.” Nothing like that. If you read her book, Push Comes to Shove, she had an early childhood full of schedules. Wake up. 6:30: Work on my English composition. 6:45: Practice my viola. All through the day. In her family, she was the first child; she was the genius child. She did it with hard hard work. As hard as we thought we worked, she worked twice as hard. I can remember being on our first tour in 1967. We were in Germany and we were dancing on some crap floor, and she cut her foot and I went up to her and said, “Twyla your foot,” and she said [loud, stern voice], “Go back to the dance!” It was just another world for me, being in the presence of that kind of energy and ambition and determination. Thank god she had the brilliance to carry this on. In seven years she made 35 pieces.

Wendy: When I met you, you had that same kind of determination in work, and that was a new world for me. The focus: just keep working working working.

Sara: That’s what we do. Things do shift as you get older. I would hear her coaching dancers, going back to Deuce Coupe, I would hear her saying things to them that she never said to us.

Wendy: Probably because you just did them intuitively.

Sara: And she also then thought about her work. Sometimes you make something and don’t know what you’re doing until you perform it, and finally you start understanding what was coming out, what that intuition was.

Wendy: I remember one thing she said, when I was in one of her “farm clubs,” which is when she had a bunch of people working, when we were doing almost like a tendu, and she said, “You must feel personally about every move.” I understood that because I already felt that and I loved hearing that from her. It’s a really simple statement but instead of saying “You must do it correctly,” she said, “You must feel personally about it.” I think that’s a key to how she brought personalities out.

Sara: Twyla was extremely generous in the studio, fun and intense to work with, so you wanted to meet the challenges. And she did it herself; it wasn’t like she was sitting back. It was great because you didn’t have eyes on you so you could do what you had to do. You weren’t being scrutinized by a master. She is fun to work with. She’d say, “What can you do?” and she’d laugh and giggle. She takes what the dancers can do and pushes them to do more. I think that’s why people love working with her. After I took time off—for three years I went out and had a company and did all kinds of things—I went back, which was a real gift to me because I had an injury, a detached retina. At that time in the early 80s when you have a detached retina, they didn’t do laser surgeries yet. You were in bed on your back for weeks on end. I had a lot of time to think, to think about who I was: I was about 37. What do I want to do now? I’ve had a company, I’ve done this touring thing. Managers wanted me to do things I don’t want to do. They would never let me do big open pieces.

Wendy: They’re gonna force you to be on a stage!

Sara: Yeah, to be on a stage, with three pieces on a program, and this and that. So I went back. As a dancer I could appreciate all the work that went into creating the choreography, creating the touring schedule, the company structure. It was like, “Oh, you’re gonna do all that for me and I can dance?!?! Fabulous!” So I truly appreciate how hard it is to make those structures and make them work.

Wendy: What pieces was she making then?

Sara: Baker’s Dozen (1979). She made Catherine Wheel (1981) during that time; she made Sinatra Songs. She made Bad Smells.

Wendy: [to the class] If you see the video of The Catherine Wheel and the “Golden Section,” Sara is really the goddess in it. You just can’t imagine anyone moving more beautifully.

Sara: Well that whole section of the dance was about transcendence/heaven. Like In the Upper Room (1986), it was the aspirational, heavenly place as opposed to the hell that was the main body of that dance. Saint Catherine was martyred at the wheel, the human family was fighting with each other, the father fucking the cat; it was horrible stuff. She meant it to be hell, malicious. Then came “The Golden Section.” It was all early David Byrne, the Talking Heads. He made the score for this piece.

¶¶¶ Questions from the students were not recorded. ¶¶¶

Featured Uncategorized 4

Dear Wendy, thanks for this illuminating interview with Sara Rudner. When I play back the dancing I’ve seen, Sara’s spellbinding movement remains fresh in my memory. She is a unique individual, full of grace and taught through example. Performing alongside her opened infinite possibilities.

Love this interview Wendy!

Still, to this day, there is not another person on the planet that moves like Sara Rudner.

Wonderful article. As a student in Ireland in the early 1980’s I used to watch videos of Twyla Tharp with this divine Goddess, Sara Rudner – it gave me such a buzz and was one of the reasons I persisted and became a choreographer. Thank you and Sara for talking about those amazing early days and opening up the mystery and genius of Twyla Tharp

Wendy – there is an error in the caption for the photo of Three Page Sonata.. The woman on the left is Theresa Dickinson (my exwife) and I think the woman on the right is Tupling.