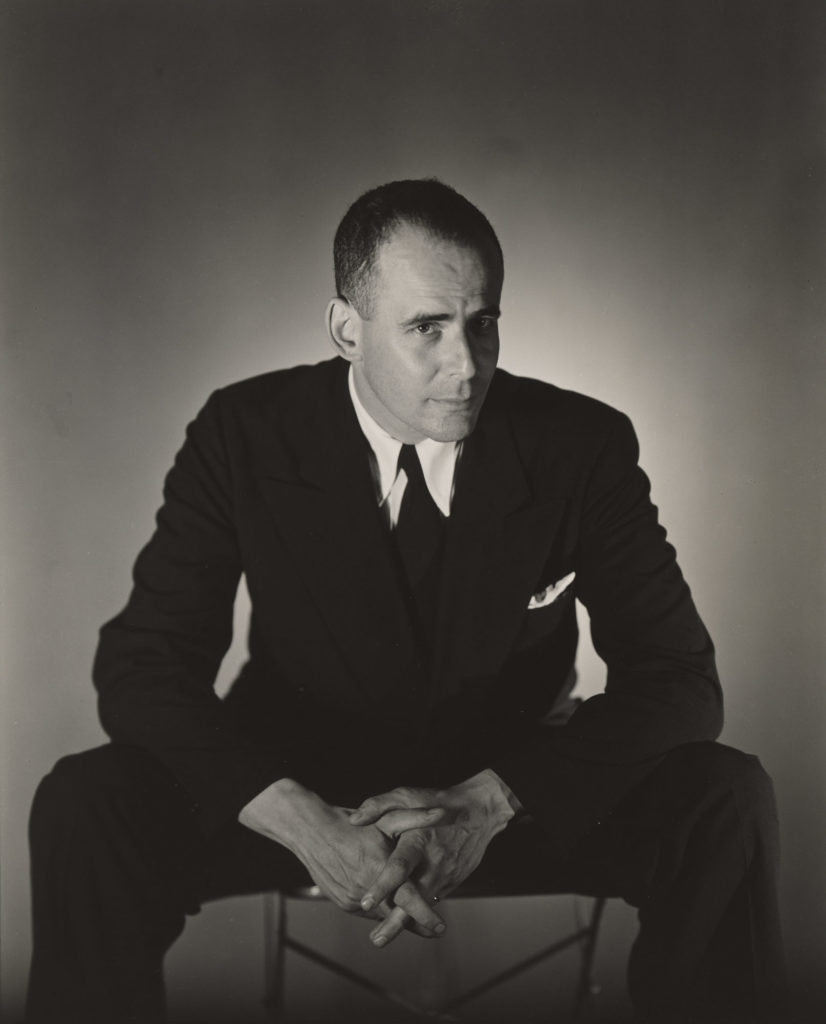

Lincoln Kirstein (1907–1996) was a remarkable man, a champion of American art as well as a purveyor of classical ballet. A Diaghilev of his time, he was an impresario, curator, patron, and more than that—a brilliant writer. In the current exhibit at the Museum of Modern Art, Lincoln Kirstein’s Modern, many of his accomplishments are on view: He helped develop the Museum of Modern Art’s collection; he wrote the scenarios and produced some of the first American-themed ballets; he co-founded the School of American Ballet and New York City Ballet with George Balanchine; and he was an early advocate for photography as art.

Kirstein c. 1948, photo by George Platt Lynes, MoMA

Behind the scenes he helped jump-start Dance Theatre of Harlem by procuring major funding; he brought budding choreographer David Vaughan over from England (who became a beacon for dance archivists); he founded the scholarly publication Dance Index (1942–49). He also marched in Selma during the Civil Rights movement, protested the war in Vietnam, and aligned himself with other social justice movements.

But one of his endeavors that is not on display, either in the galleries or in the catalogue, is his long and nasty crusade against modern dance.

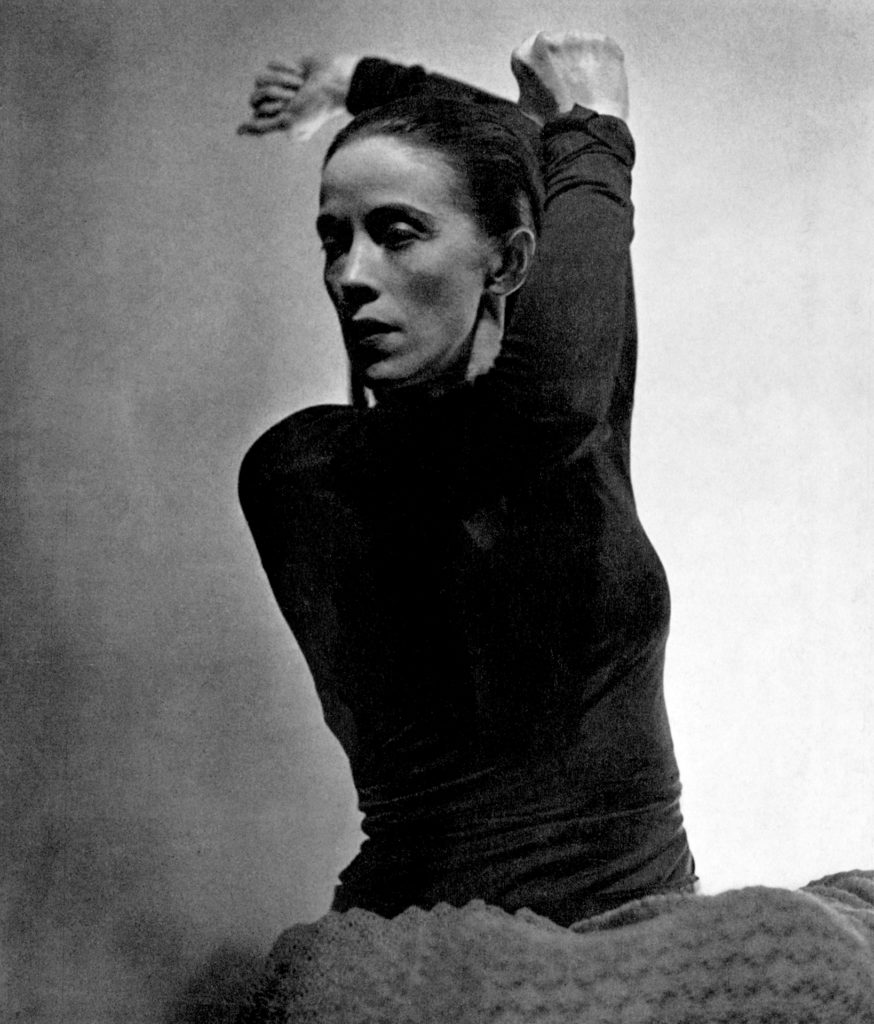

As the wall text at MoMA states, Kirstein had “omnivorous interests.” Early on, modern dance, which he sometime called free-form dance, had been one of those interests. He was “magnetized” (his word) by Martha Graham and they became good friends in the mid-30s. He called her “one of America’s greatest artists” and waxed eloquent about her choreography. In a 1937 article he wrote, “She has created a kind of candid, sweeping and wind-worn liberty for her individual expression at once beautiful and useful, like a piece of exquisitely realized Shaker furniture or homespun clothing.” In 1942, Kirstein devoted the first issue of his Dance Index to Isadora Duncan. (This edition is on display at MoMA.)

Graham in Chronicle (1936) Courtesy Martha Graham Resources

Sometimes, however, these interests turned into targets for Kirstein’s shooting practice. In a 1986 tirade in The New York Times titled “The Curse of Isadora,” he wrote that while ballet is “a three-ring circus; free-form dance is a side-show with its oddballs, freaks and phonies.” The same year, in an interview in The New Yorker, he said that the post-Graham dance artists either glommed onto ballet (e. g. Tharp) or were minimalist, in which case “There is nothing to look at.” Further, he claimed that “there was never any interest in training children” among modern dancers. The ignorance, voiced authoritatively, is quite stunning.

Although Kirstein invited Martha Graham to collaborate with Balanchine on Episodes (1959), he said privately that he did so because it was “politically useful.”

At a meeting with the Ford Foundation in the 1960s, to which several dance companies were invited, he said something like, “All Martha’s works are about elimination. She dances about shit.” (This was an out-loud variation of what he’d written in his diary after his first view of Graham in 1931: that her work was “a cross between shitting and belching.” But this particular quote comes direct from a recent conversation with former Graham dancer Stuart Hodes.) You could guess how much money the Graham company was awarded as a result of that meeting.

Kirstein’s contempt for modern dance was not a fluke. He’s part of a lineage, a tradition if you will, in the ballet world of throwing shade on modern dance. Michel Fokine had referred to Graham and Harald Kreutzberg as “the horror.” (This is not hard for me to believe. As a teenager, I showed my ballet teacher, Irine Fokine, Michel’s niece, a brochure from the concert I’d seen the night before: a Martha Graham program. She looked at the pictures and said, “How can you like something this ugly?”). The New Yorker critic Arlene Croce, who became a leader of the Balanchine-above-all circle, periodically went slumming and took random potshots at downtown choreographers. She pretty much toed the Kirstein line of celebrating Balanchine ballet while questioning the legitimacy of modern dance.

Walker Evans’ Roadside View, Alabama Coal Area Town. 1936. MoMA. Evans was one of the photographers championed by Kirstein.

In the wall text, MoMA refers to Kirstein’s “expansive view of what art could be.” But this simply did not apply to dance. For him, ballet was the supreme form while modern dance was a passing trend. In his preface to the Balanchine Foundation Catalogue, he calls Balanchine ballets a “paradigm of perfection.” Like the choreographer, he referred to ballet dancers as angels. So lovely, so innocent, so close to heaven. . . So obedient. Balanchine’s steps came mostly from ballet’s codified vocabulary, a.k.a. “the academy,” and the dancers executed these steps. Graham, on the other hand, had the temerity to create her own movements. So, although Kirstein was initially “addicted” to Graham’s work (according to Agnes de Mille), he later denigrated it.

The irony is that Kirstein’s earlier company, Ballet Caravan (1936–1941), had found a warm welcome in the modern dance world. The company debuted at the Bennington School of the Dance (the stronghold of early modern dance), and his booking manager, Frances Hawkins (also Graham’s agent), booked the company into the college circuit laid down by Graham and Doris Humphrey. He favored specifically American themes; according to Sally Banes, he shared with Graham and Humphrey “an urgent search for national identity.” Kirstein himself, in Thirty Years: New York City Ballet, wrote, “In an important sense, Modern Dance may be said to have launched Ballet Caravan.”

Another point made in the wall text at MoMA: When Kirstein traveled to South America to acquire works for MoMA, he was looking for artists who “have attempted to declare independence from traditional European expression.” Of course, this is exactly what Martha Graham was doing: breaking away from European ways of dancing and staking out a distinctively American terrain.

Primitive Mysteries (1931) by Martha Graham. Photo by Barbara Morgan. Courtesy Martha Graham Resources.

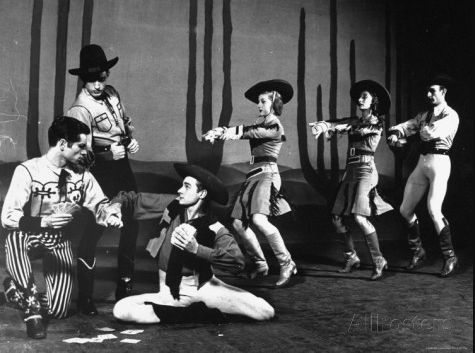

On large screens, the MoMA exhibit shows short clips (shot by Ann Barzel) of several of the ballets Kirstein commissioned for his Ballet Caravan, and they look pretty corny. In Lew Christensen’s Filling Station (1938) and William Dollar’s A Thousand Times Neigh! (made for the Ford Pavilion at the World’s Fair, 1940), the characters are broadly drawn. We see literal, almost pantomimic portrayals, and plots that are often excuses for multiple jumps and turns. To me, these ballets (granted, brief clips without music do not tell the whole story) look like children’s theater. Even Eugene Loring’s Billy the Kid (1938), which did have an afterlife, looks hokey now.

Michael Kidd and John Kriza of ABT in Billy the Kid, 1944.

By contrast, Graham’s works like Chronicle (1936) and Primitive Mysteries (1931) have stood the test of time. The all-women’s group in Chronicle, now being performed at the Joyce by the Martha Graham Dance Company, gathers force as it welds design and emotion together. Each movement, whether rooted or springing upward, is essential to this ode to human power in the face of growing fascism. Graham’s signature works of the 30s broke new ground in the dance wing of modernism, while most of Kirstein’s ballets of the period were insignificant, except for his insistence on using American composers.

Xin Ying in Chronicle, photo by Melissa Sherwood

Considering the artistic flimsiness of Ballet Caravan’s rep, Kirstein’s verbal darts aimed at Graham were not only cruel but preposterous.

Regarding other modern dance figures, Kirstein was hardly more charitable than he was with Graham. When he invited Merce Cunningham to choreograph for Ballet Society (the precursor to NYCB) in 1947, he was ready with clever put downs for Cunningham and John Cage, who wrote the score: He called them “minor anarchs.” Not surprisingly, he also had words for Alvin Ailey (“tasteless vitality”).

To put these put-downs in context, he flip-flopped on many people in the arts, applying superlatives one week and degrading remarks the next. (This was true of his treatment of ballet icons Arthur Mitchell and Jerome Robbins as well as of Duncan, Graham, and Cunningham.) Diagnosed with manic-depression, Kirstein was first institutionalized in 1967. Martin Duberman, his biographer, even implies that his more outrageous slurs were caused by manic phasees. Jacques d’Amboise describes occasions when Kirstein viciously insulted an artist soon after praising him or her. (The way d’Amboise tells it, these tales of Kirstein’s uncontrollably boomeranging opinions can be very funny.) I sometimes think that most of the ballet world considers it rude, or at least indelicate, to point out the unhinged ravings of such a respected figure. But these “fulminations,” to use Sally Banes’ term, had damaging effects, and one of them was to deny funding to modern dance. Another was, as I’ve mentioned, to give permission to treat modern dance as an inferior art form.

Today ballet and modern dance are less polarized. One of the qualities of the latter that most appalled Kirstein—the earthbound mode (as opposed to the airiness/loftiness of ballet)—has seeped into the work of current ballet makers. For both Justin Peck (NYCB resident choreographer) and Alexei Ratmansky (artist in residence at American Ballet Theatre), the floor sometimes exerts a magnetic pull. Another sign of the closer relationship between the two genres is that, in this centennial year of Cunningham, the master’s works are being performed by companies like Ballet West and The Washington Ballet. And of course, it’s thrilling that NYCB invited (post)modern dance artist Kyle Abraham to contribute to its repertory—and that The Runaway, with music by Kanye West and Jay-Z, was such a runaway hit.

But there is still a privileging of ballet that pervades dance training, performances, and criticism. Perpetuating that hierarchy, The New Yorker has just appointed Jennifer Homans as its new dance critic. Homans, author of Apollo’s Angels (meaning of course, Balanchine’s dancers), has established the Center for Ballet and the Arts, a well-funded project at NYU that announces the primacy of ballet in its very title. And so the privileging continues.

Sources:

• Lincoln Kirstein’s Modern, MoMA exhibit.

• The Worlds of Lincoln Kirstein, by Martin Duberman.

• By With To & From: A Lincoln Kirstein Reader.

• Ballet: Bias and Belief, Three Pamphlets Collected and Other Dance Writing of Lincoln Kirstein, Dance Horizons, 1983.

• I Was a Dancer, by Jacques d’Amboise.

• “Lincoln Kirstein, Modern Dance, and the Left: The Genesis of an American Ballet,” by Lynn Garafola, Dance Research Journal, v. 23, no. 1, Summer 2005.

• “The Curse of Isadora,” by Lincoln Kirstein, The New York Times Archives, Sunday, Nov. 23, 1986.

• “Profiles: Conversations with Kirstein — 1,” interview with W. McNeil Lowry, The New Yorker, Dec. 15, 1986.

• “Sibling Rivalry: The New York City Ballet and Modern Dance,” by Sally Banes, in Dance for a City: Fifty Years of New York City Ballet, edited by Lynn Garafola with Eric Foner.

Great article Wendy 👍. Did not know he was hospitalized.

One thought that crosses my mind after reading this strong essay, Wendy, is that modern (or ‘contemporary’) dance should adopt Graham’s habit of referring to her ‘works’ or ‘pieces’ as “ballets.” That might make Kirstein roll over … in a good way. Go the other direction! Refer to a ballet by Steve Paxton or Merce Cunningham. There is nothing inherent in the word that precludes such a use, and maybe the word itself is reinforcing the silos you describe.

ballet (n.)

“theatrical, costumed dance and pantomime performance telling a story and representing characters and passions by gestures and groupings,” 1660s, from French ballette from Italian balletto, diminutive of ballo “a dance,” from Late Latin ballare “to dance,” from Greek ballizein “to dance, jump about” (see ball (n.2)).

I’d like to find out if Martha Graham herself decided to call her works ballets, or if it was Ron Protas’s idea. In any case, I think “ballet” as a noun has an elitist ring to it. And it would be hard to call a work by Steve Paxton a ballet, or a tap or hip-hop work for that matter.

Yes, I’ve wondered about that too- that dances, works of art are called “ballets”. I was surprised by this delineation.

I believe Graham referred to her works as ballets long before Protas came along. I can hear her voice saying the word, so perhaps in the film that was made in the late Fifties, “A Dancer’s World.”

And to shift the subject a bit, I think this is a thought-provoking essay indeed, but Kirstein was such a large figure in American cultural life, and such a complicated man–he was bipolar before decent drugs were developed to deal with what is a biochemical disease–we have to be careful and thoughtful in our assessments of both the good that he did and the damage. The first certainly in my view outweighs the other. I must first point out about A Thousand Times Neigh that this was a work, by William Dollar, that was intended to sell cars, and much more important, provide paid work for dancers, which it did for six months. Ballet Caravan, which in part was founded for the same reason, had nothing to do with it; it had been disbanded before the World’s Fair I believe. To group this overtly commercial work with Billy the Kid and Filling Station is both unfair and inaccurate I’m afraid. And those two works have endured, incidentally. I’ve seen the Joffrey Ballet, Pacific Northwest Ballet, and the Dance Theater of Harlem dance Billy the Kid, which choreographically could conceivably be characterized as post-modern for its mixture of pedestrian movement, classical ballet, and modern movement. It is moreover a reflection of American popular culture (I forget when the first film about B. the K. was made, but possibly in the Twenties) with an anti-hero as its leading character. Like some of Graham’s work, it has Freudian undertones (Billy becomes a killer after his mother is stabbed to death). Yes, it has hokey and dated details, but Loring has been seriously underrated as a choreographer and someone (not me) needs to write a book about him. As for Filling Station, this is an anti-elitist ballet, in which a member of the working class is the hero, executing grand jetes and pirouettes, a Rich Couple, drunk, gets robbed, truck drivers do a vaudeville turn, and such social dances as the Big Apple are incorporated into the choreography. Virgil Thomson wrote the score, Paul Cadmus did the stage design, Lew Christensen the choreography, all of them American artists. As for Kirstein’s hostility to all modern dance, whoa! He has to have known that Todd Bolender had been a student of Franziska Boas and Hanya Holm when he recruited him from Muriel Stuart’s class at SAB for Ballet Caravan in 1938. Bolender used some of that modern technique in the role of Alias in B. the K. Moreover, Kirstein (and Balanchine) supported Bolender as a crossover choreographer, the former particularly for The Miraculous Mandarin, Kirstein’s indeed nasty letter to someone quoted in Duberman’s biography notwithstanding. The Still Point too is laced with modern movement, reminiscent of Holm’s. I’ll say no more here; in a few months (I hope) those who are interested can read more details in a book I’m finishing about Todd Bolender and Janet Reed and their roles in the flowering of American ballet.

Martha, thanks for all this info. If A Thousand Times Neigh was made just to sell cars at the world’s fair, then MoMA should not have displayed it along with more serious pieces. I guess the film evidence was limited by what Ann Barzel happened to capture with her camera. I remember that Gloria Fokine, who grew up in Cuba, was delighted by Filling Station when it came thru, mostly because of the nifty cellophane costume and American content. Btw, I did say that Billy the Kid had an afterlife. As for the nasty letter quoted by Duberman, that would be plural, as there were many nasty letters, only some of which appear in Duberman’s excellent biography.

A Thousand Times Neigh received glowing reviews from multiple critics, including Gilbert Seldes and John Martin. By all accounts it used serious technique and was as demanding as any other work put on by Ballet Caravan. And it was indeed presented by American Ballet Caravan – it was the last project they mounted before disbanding – although it did employ many other dancers since it was double cast to allow dancers time off. Twelve performances of it were presented each day.

It did have a commercial patron and occasion, but it was still regarded as a non trivial work. There is every reason in the world to include it in the MoMA exhibit.

I heard Graham refer to her works as “ballets” in an onstage speech in 1979. She also referred to “contemporary dance”.

Thanks for that date cuz several people have been asking about when that changed. As for the word “contemporary,” the plaque in front of her school, at least as of 1963 when I started studying there, read “The Martha Graham School for Contemporary Dance.” It struck me as odd, since she was the icon of modern dance, and contemporary dance was Merce’s territory.

Right on, Wendy!

I do not have anything to add other than my admiration for the clarity of what Wendy has written. I was completely engaged. I sensed her being hot under the collar by it all but it did not spill out as tirade but rather as clear and level headed thinking. Thank you.

I was “hot under the collar” the first time I read one of Kirstein’s drive-by shootings of modern dance in the 70s. It was in the NY Times Arts and Leisure, a precursor to his “Curse of Isadora” essay that I quoted here. Maybe I’ve taken all that time to cool down a bit. But I was glad to have an occasion to look into this a little bit further.

Wendy, you’ve written a fine piece. But on the matter of using “ballet” to refer to modern dance: When I moved to NYC in 1964, I attended the American Dance Festival program at Connecticut College in honor of Louis Horst. There were pre-performance speeches by Martha Graham and Jose Limon, and during the course of her remarks (AS I RECALL! — memory is fallible, but I’ve always remembered this), Graham referred to her dances as “ballets,” then turned to Limon and said something to the effect of “You don’t mind if I call them that, do you?” AS I RECALL, Limon simply shrugged and changed the subject. But Graham’s term impressed me then, as it might now: Why shouldn’t an example we of Western theatrical dance be called a ballet. I ALSO RECALL that when she led the National Association for Regional Ballet Doris Hering referred to ballet as any form of dance “raised to a theatrical level.”

OK, so she was calling her works “ballets” as early as 1964. I wonder if Erick Hawkins was an influence in that usage.

For those of you who want to know more about the Horst memorial or anything else in the the summer of 1964 at ADF, I recommend Jack’s book “The American Dance Festival” (Duke U Press, 1987). It’s a great account of those summer intensives in modern dance from 1948 to 1985. I have burrowed into it many times.

Dear Wendy,

Kirstein was often excessive, Intemperate. He enjoyed blasting at various targets; he still deserves to be blasted for some of his excesses. Take care, though, that the same may not be said of you.

1. The climate in which Kirstein discovered American dance was quite different than ours. John Martin, the “New York Times” dance critic, held that modern dance was an American dance genre, and that ballet was European. He, Martin, praised Russian ballet when it seemed Russian, foreign, exotic. When Frederick Ashton had a success here in 1934 with the avant-garde triumph of “Four Saints in Three Acts” (with its all African American cast), Martin nonetheless advised him to return to Europe; it took Kirstein over fifteen years to win Martin round to admiring Balanchine. Under Martin, modern dance was where the “New York Times” was on home ground; and during the long subsequent regime of Anna Kisselgoff at the “New York Times”, during which Kirstein wrote his 1986 “Times” diatribe against modern dance, Graham was probably sanctified more than Balanchine in that newspaper. Kirstein seems mightily influential to us; but he was often fighting against the current. His “Blast at Ballet” is still worth reading: he’s blasting the establishment (Russian ballet, critics, the Met Opera), not modern dance.

I don’t condone his more misguided remarks in later years. (It’s dangerous to quote his unpublished remarks, many of which reflected his glee in sounding outrageous off the record. I only met him properly once, but I recall that his many negative remarks were largely directed at ballet; I dimly remember him even swiping at one Balanchine ballet performed that evening, “Brahms Schoenberg Quartet”.) But his larger point against modern dance was that it tended to promote idiosyncrasy, whereas ballet’s impersonal tradition and academy were more selfless and enduring. He himself exonerated Paul Taylor and (sometimes) Graham from this charge; he found their best work exemplified classical values – not ballet’s classicism but one he admired. We may disagree about his “idiosyncrasy” point, but it’s an interesting one to consider and debate.

2. When Balanchine went off to work in musicals, Kirstein kept his ballet project going with such ballets as Lew Christensen’s “Filling Station”. Contrary to what you say, this has stood the test of time. It’s worth reading what Marcia B. Siegel wrote about that and other Ballet Caravan Americana in her important survey, “The Shapes of Change”. “Filling Station” was revived by San Francisco Ballet in 2008, while you were editor of “Dance Magazine”; more than one New York critic attended.

3. “The ignorance, voiced authoritatively, is stunning.” Those are your words about Kirstein; so again, be careful – you don’t do credit to Arlene Croce. She too was controversial, but she was by no means a card-carrying Kirstein acolyte. I quote you: “The New Yorker critic Arlene Croce, who became a leader of the Balanchine-above-all circle, periodically went slumming and took random potshots at downtown choreographers. She pretty much toed the Kirstein line of celebrating Balanchine ballet while questioning the legitimacy of modern dance.”

Yet when I thumb through her “Afterimages” (1977), I find positive “New Yorker” reviews written by her of Graham, Cunningham, Taylor, Tharp (whose “Sue’s Leg” she traveled to see in St Paul), Laura Dean, Senta Driver, Merle Marsicano, Kathryn Posin, Annabelle Gamson, and others. In her Marsicano review, I note she has bothered to research a 1954 “Dance Observer” review by Richard Lippold. You, by contrast, didn’t even pay attention to the credits to the 2017 “Radical Bodies” exhibition of postmodern dance at the New York Public Library for the Performing Arts, where Yvonne Rainer’s contributions to “Ballet Review”, specifically commissioned by Croce before her “New Yorker” days, were shown.

To accuse her of “questioning the legitimacy of modern dance” is drastic on your part. Can you provide a single example of this questioning of hers? In her twenty-five years as chief dance critic of “The New Yorker”, Croce only published three profiles (in the days when that magazine published extensive profiles, some of which became the basis of book-length biographies). Only one of these was about a Balanchine subject, Edward Villella. Her first was of David Gordon and Valda Setterfield: it addressed not only those two but the whole field of postmodern dance. Though she, Croce, did not love Trisha Brown as a choreographer of group dances (until 1989), she certainly praised her in very high terms as a soloist. And, when noting how little inroads postmodern dance had made into mid-America, she, referring positively to Sally Banes’s “Terpsichore in Sneakers”, wrote wittily and sympathetically that at this rate Terpsichore would be in carpet slippers by the time she made it to Arkansas. She’s very far from questioning its legitimacy; and she disagrees with Kirstein more than once.

She also refers to two Balanchine ballets as “junk” (see p.309 of “Afterimages”). And she ends one 1969 essay on the young, pre-ballet, Tharp by saying “I know only two other choreographers who give the same effect, and they’re Mr. B. and Merce.”

During the course of the 1980s, Croce wrote a series of Mark Morris reviews that were widely considered to have put him on the map. She went on reviewing Taylor and Cunningham, mainly positively; in 1989, she came round to Trisha Brown to the extent of writing “this was the season I fell in love with ‘Opal Loop.’”

Apart from the Gordon/Setterfield profile, all this (unlike a 1955 copy of “Dance Observer”, say) is easily found today. Yet you chose not to find it. I’m afraid it reads as if you prefer to be prejudiced against Croce than to check the facts. Sure, she disliked plenty of postmodern dance; she disliked a great deal of ballet too, and blasted it in equal measure.

It’s worth remembering that ballet and modern aren’t the only two dance genres. Croce never made that mistake. Her first book, a classic, was about Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers; her most recent published writing (“New York Review of Books”, February 2016), about American tap dance and Brian Seibert’s book, showed her long devotion to tap, not least to its foremost African American exponents.

4. Kirstein’s handwritten 1930s diaries, now in the New York Public Library for the Performing Arts, show that he sought out a wide variety of modern dance. He was dismissive of Doris Humphrey, derisive of Ted Shawn, seriously interested by Hanya Holm; he enjoyed the company of Jane Dudley, with whom he liked arguing about various dance forms and whose left-wing politics appealed to him. Writing in private, he was sometimes rude about Martha Graham (January 18, 1935: “phonier than I even thought; a lot of repetitious, unimpulsive Romanticism”), but, remarkably, he was contradicted on Graham (February 10, 1935) by Balanchine, who disliked her choice of music but thought her talent “superior to Massine’s”. (Balanchine also “liked her body & hair & wd. like to baise her.”)

You can tell that Kirstein, Balanchine, and Pavel Tchelitchew (their companion that evening, and Graham’s keenest defender in the group) all enjoyed discussing Graham. Sure, Kirstein is the one who resists Graham most; but it’s fascinating to see how he’s prepared to reconsider and to report what others said to him. He’s one of those people who are more interesting to disagree with than many others whose opinions are less exceptionable.

Best

Alastair

Alastair, I am not as fascinated with Kirstein’s opinions as you are. Once one knows that he liked the military and liked order (a twin preference that often crops up in his writings), it follows that he didn’t like dance artists (with the exception of Mr. B) to be spontaneous or creative. Too much hint of chaos for him. Another aspect is the supposedly spiritual thing. The good angels are Balanchine’s dancers, and the “black” angels are comparable to modern dancers whose “sin” is to not respect tradition (page 201, By With To & From: A Kirstein Reader.) These are simplistic opinions. I am more concerned with his power. People who have power often use their opinions as weapons without even realizing it. This is what is damaging and the reason I’ve written about his opinions.

In seeking to demonstrate that Kirstein wasn’t the only one who voiced what I would call ballet supremacy, I mentioned Arlene Croce. I admit it would have been more accurate if I had specified the downtown subsection of modern dance as a target rather than all of modern dance. Over many years my strong impression—and that of many of us downtown—was that she would periodically group a bunch of downtown dance-makers together and write very dismissive things. In the June 30, 1980 edition of The New Yorker, she proposed a genealogy of downtown dance that was reductive and off-base, claiming that Robert Wilson was as influential as Cunningham. This column prompted letters from Yvonne Rainer, Meredith Monk, and Kenneth King, who himself had influenced Wilson, all trying to give credit where it was due. Nevertheless I thank you for pointing out that Croce “was by no means a card-carrying Kirstein acolyte.” My apologies go to her for making that assumption from afar.

I stand by my claim that Kirstein was ignorant about the training of modern dance. Certainly the techniques of Graham, Humphrey, and Cunningham, though not requiring as long an apprenticeship as ballet, are also rigorous. I know this not from any quotes but from my own long years of serious training (including two intensive summers at the School of American Ballet). After Kirstein’s momentous decision to bring Balanchine here, perhaps he was, in a sense, protecting his investment by making this unfair claim. It’s true that there is not a single, agreed-on training method in modern dance, but the individual approaches add to the richness of the field. Martin Duberman, his biographer, said that Kirstein basically felt that ballet had replaced modern dance after the 30s. Again, this, to me, is not an “interesting” opinion but a destructive one, considering how close Kirstein was to the funding establishment.