Note: Cunningham, the 3D film, opens in theaters in the U.S. on December 13, 2019. This posting is adapted from my preview appearing in the December 2019 issue of the Berlin-based journal, Tanz.

Merce Cunningham was never interested in a linear path of beginning, middle and end—in time or in space. He liked to make dances where you experienced everything at once, where the movement, sound, and visual design rushed at you—seemingly unrelated. He wanted the dancers to move through a field of space, not just the stage with its two-dimensional proscenium setting. In this centennial year, the 93-minute film Cunningham, directed by Alla Kovgan, indulges that wish.

Alla Kovgan,, photo by Martin Miseré

With his groundbreaking ideas and quicksilver choreography, Cunningham ushered in the American phenomenon of post-modernism in dance. No longer was a story necessary to hang the choreography on. No longer was the center of the stage the center of attention. Dance could exist anywhere, and any kind of movement could be dance. “No fixed points” was a phrase he coined, meaning the dancing does not need to have a single front. This was part of his pledge to expand the possibilities for dance. It’s a particularly American exploration, parallel to composer John Cage’s idea that any sound can be music.

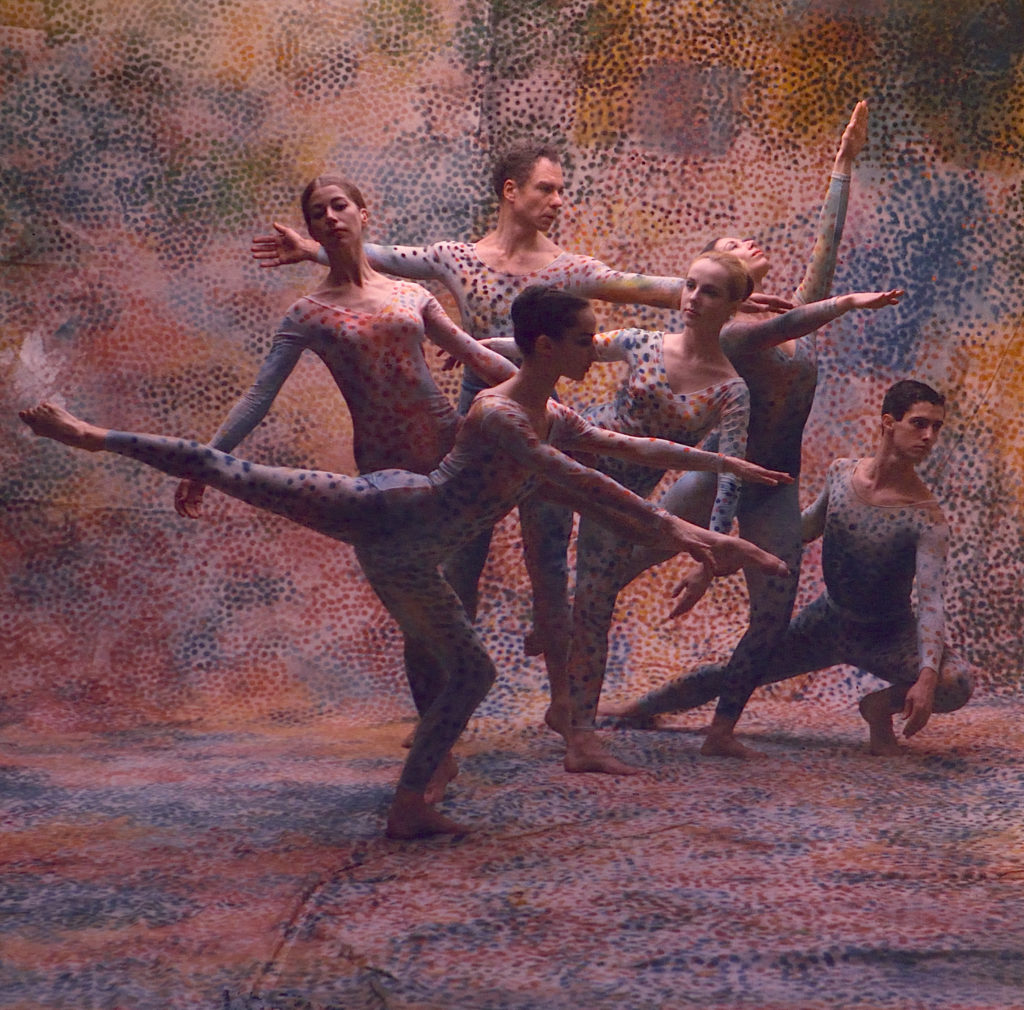

Thus it is surprising that a young filmmaker from Russia—that land of classical ballet—has produced such an illuminating film on Cunningham’s life (1919–2009) and work. Kovgan has dug deep into his vast output—vast in amount of choreography, and vast in the distance he traveled away from the theatricality of early modern dance. Kovgan, who considers herself a “formalist at heart,” was inspired by a photo of Summerspace (1958) with the no-center, pointillistic décor by Robert Rauschenberg, in which Cunningham tried to create an immersive environment.

Summerspace with, from left: Viola Farber, Carolyn Brown in arabesque, Merce Cunningham, Shareen Blair, Judith Dunn looking up, and Steve Paxton, photo by Richard Rutledge c. 1961

The film interweaves black-and-white archival footage with a series of new reconstructions in several sumptuous sites, shot in 3D. In the opening scene, you feel you are inside a long tunnel, slowly approaching a sole dancer. It doesn’t matter what the dancer is doing; what matters is the eerie, telescoping sensation conjured by the 3D camera. Other environments, all for current dancers directed by Jennifer Goggans, include a pine forest, a clearing near a pond, a ballroom, and the Westbeth rooftop next to the Hudson River. Each new setting floods the senses; the 3D effect envelops you in the space, illustrating the point that Cunningham envisioned dance in a field as opposed to a flat space. The camera moves in such a kinetic way that you feel you are inside the action. In the reconstructed Rainforest (1968), you feel as though you could almost tap Andy Warhol’s silver pillows away.

Westbeth Rooftop, photo by Mko Malkshasyan

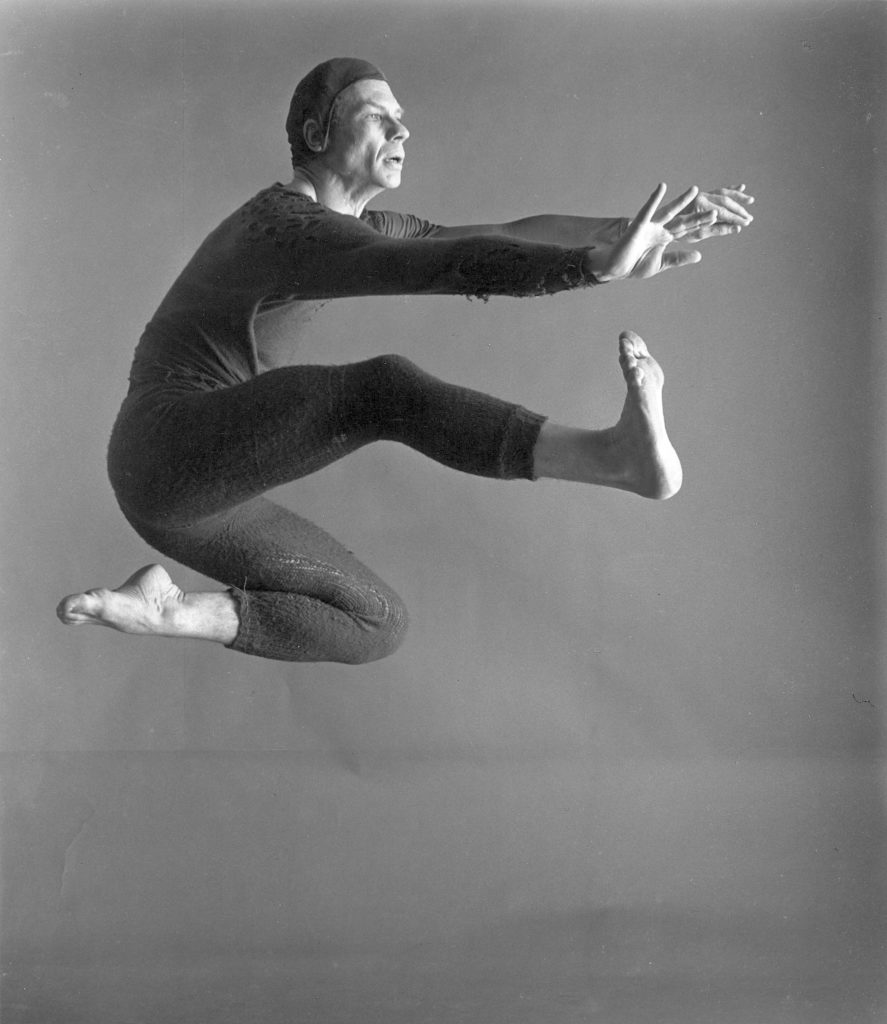

The early footage of Cunningham dancing solo reveals the explosive quality of his dancing. He threw himself into odd, chance-derived movements that were both wild and precise. His fervent energy was unstoppable. In the 60s, when the work was still new, his dancers were distinct individuals. I found the archival close-ups of Carolyn Brown, Viola Farber, Sandra Neels, Barbara Dilley, Gus Solomons, jr, and Valda Setterfield to be especially poignant. Dilley comments that Cunningham left space for them to be themselves within the choreography. (That became less true as the age gap between Cunningham and his dancers widened.)

The soundtrack includes comments from Cunningham and Cage that reflect their philosophy. For example, we hear Merce saying to a journalist, “We don’t interpret something. We present something, we do something, and then any kind of interpretation is left up to anybody looking at it in the audience.”

Merce Cunningham in Changeling (1957) photo by Richard Rutledge ,Courtesy_Magnolia

The different modes of archival footage, the 3D reconstructions, portraits, and interviews coexist, sometimes simultaneously. As with Cunningham’s choreography, you are encountering several modes at once so it feels like all your neurons are firing as you watch. Even though the reconstructions include only dances between 1944 and 1972, for example Septet (1953), Antic Meet (1957), and Winterbranch (1964), all these elements come together to form a complete picture of Cunningham’s oeuvre. The variety of modes invites us to experience his work rather than to categorize it. And we get to hear about his own subjective experience: “Inside of all that is an ecstasy, brief perhaps, not always released, but, when it is, it is like a moment in balance when all things great and small coincide.”

It took years before Cunningham’s work was accepted, and it is still considered controversial. Replying to a journalist asking about the negative reactions in the early days, Merce says, “No matter how dire the situation was, how desperate, I would wake up one day and start to work and suddenly realize that it was just as interesting as it always had been.”

Poster outside Walter Reade Theater in Lincoln Center

Schedules and tickets in NYC are available at Film Society of Lincoln Center and Film Forum. To see the trailer and schedules in other cities, go to Magnolia Films.

Featured 1

This film on Merce has just opened in Tel Aviv and so I am VERY glad with my tight schedule (of what to do with whom during my remaining days and nights here) to read Perron’s perspective with all-firing-nerons-needed to watch what she says is clearly a commendable film about Cunningham’s amazing output.