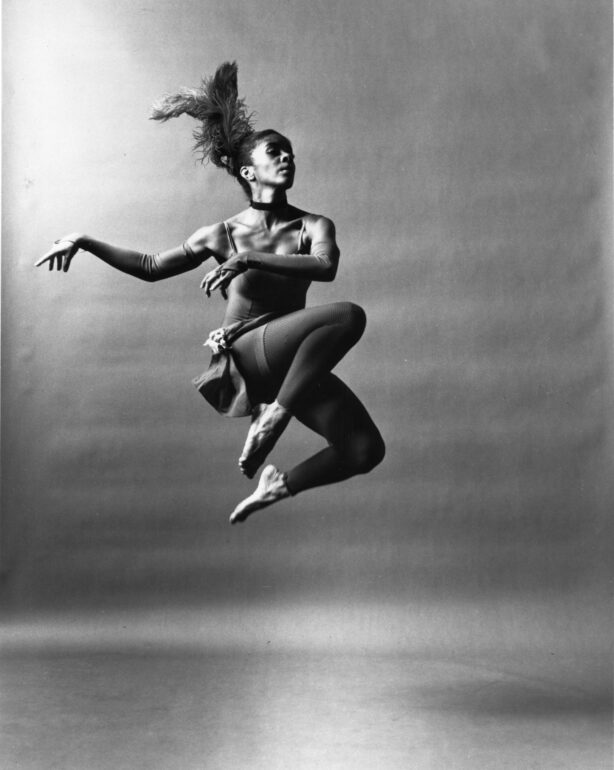

I wrote this preview of the PBS documentary “Free to Dance” for the New York Times, which published it on June 17, 2001. The passing of Charles Reinhart has prompted me to post it now because “Free to Dance” came out of a larger program that Charlie and his wife Stephanie launched called The Black Tradition in American Modern Dance. It was also made into a book written by Richard A. Long with annotated photos by Joe Nash. Charlie and Stephanie were executive producers on “Free to Dance,” which is now available on YouTube. The Reinharts received a joint Dance Magazine Award in 2003, she posthumously. Looking back at what I wrote, I see it as not only a preview, but as a brief overview of Blacks in twentieth-century concert dance. I’ve inserted photos (mostly from the Joe Nash collection), links, and phrases in brackets that supply relevant material. The headline given by the NY Times editors was “The Struggle of the Black Artist to Dance Freely.”

“Free to Dance,” a richly resonant new documentary from PBS, shows how Black dance artists honor their heritage and transform their responses to society into glorious dancing. It also challenges the conventional wisdom that modern dance was a creation of white choreographers.

One of its revelations is the heartbreaking correspondence between Edna Guy and Ruth St. Denis. Guy, a Black teenager ardently dedicated to dance, appeals to ”Miss Ruth,” icon of ”aesthetic dancing,” for advice on how she can become an artist. St. Denis, who begins her letters ”Dear Girlie,” at first denies Guy access to classes at the Denishawn school, but later, in 1924, opens the doors. [Edna Guy worked closely with Hemsley Winfield before he died at 28 years old.]

Instead of graduating into the company like the other girls, however, Guy is relegated to the job of seamstress. Discouraged, she creates dances with her friends to Negro spirituals and gets ousted from the company altogether. On the rebound, Guy immerses herself in the Harlem Renaissance and eventually invites Katherine Dunham to perform in New York in 1936, becoming a key link in the history of Blacks in dance.

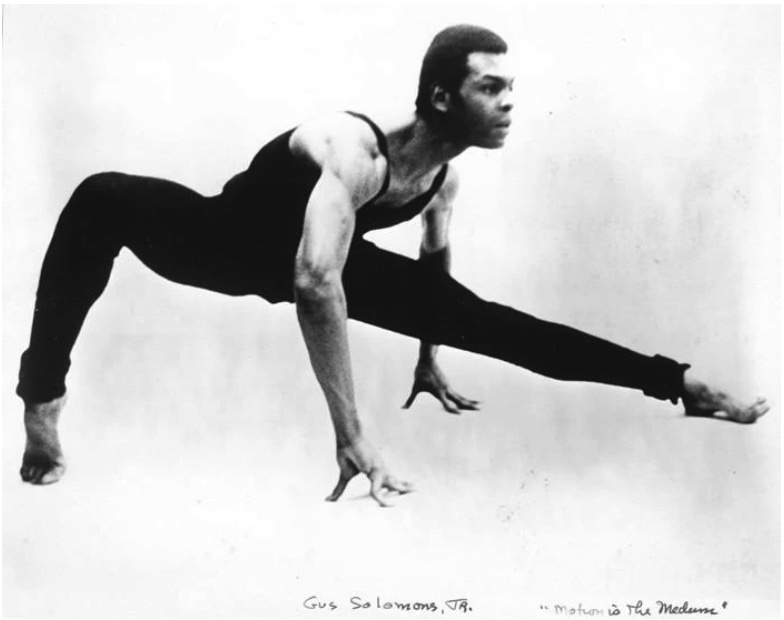

A sense of freedom gained through struggle permeates the dancing on the screen as well as in the words of the performers interviewed in ”Free to Dance,” which will be shown as part of WNET’s Dance in America series next Sunday [June 24, 2001]. From Ms. Dunham, the ground-breaking dancer and anthropologist, to the Cunningham-influenced Gus Solomon’s jr, we see the wide array of choices that Black choreographers have made about how—or whether—to draw on their cultural heritage.

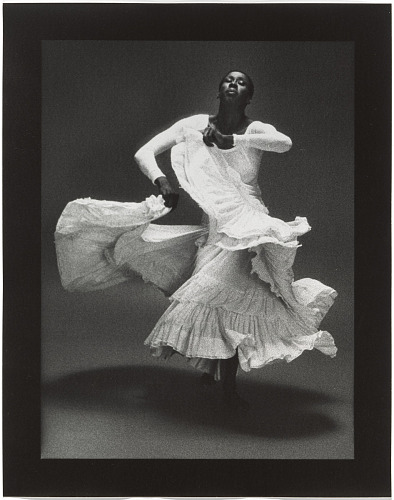

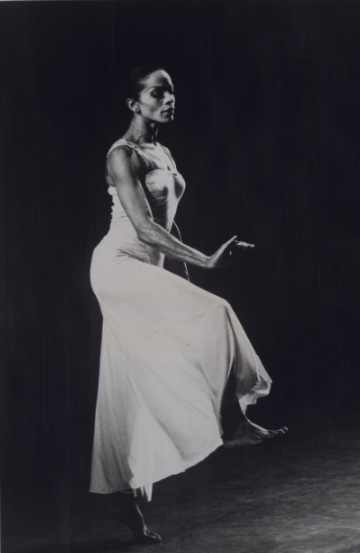

The connection of dance to daily life is kept in focus throughout the three-hour program. Ms. Dunham says of her research in the Caribbean, ”I could not learn the dances without knowing the people.” Just as Ms. Dunham participated in spirit-possession rituals in Haiti, Pearl Primus picked cotton in Alabama. Modern dance is not something remote and fantastical but connected to real lives, from the chain gangs of Donald McKayle’s ”Rainbow Round My Shoulder” (1959) to the domestic worker portrayed in Alvin Ailey’s ”Cry” (1970) to the young people dancing in clubs in Talley Beatty’s ”Stack Up” (1982).

Political awareness is inevitable. The dancer Jacqueline Goldman says, ”I heard Alvin Ailey’s dream before I heard Martin Luther King’s dream.” The issue of police brutality crops up as a child’s rhyme in Mr. McKayle’s ”Games” (1951).

The communal spirit of the circle, as seen in the clapping and stomping ring-shouts of plantation dances and the Black Bottom of the 1920’s, threads through the evening. Juxtapositions between the old and the new affect us on a subliminal level. Bill T. Jones, dancing his 1987 solo ”Etudes,” repeats a twisting movement, body low, arms swaying side to side in response to swiveling hips—a lyrical version of the twist.

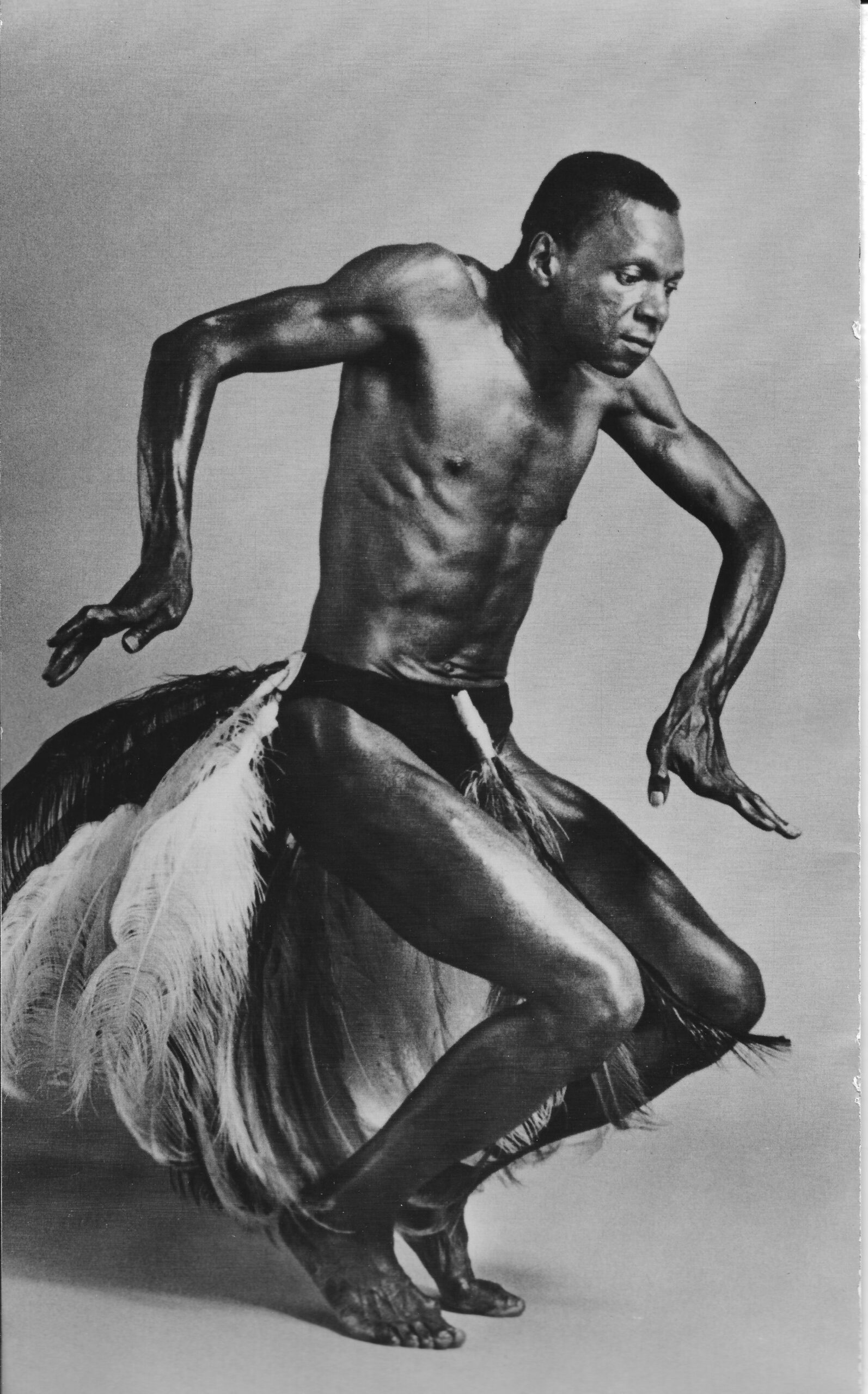

Similar motions surface in the footage of ring-shouts of former slaves and the movements of the West African choreographer Asadata Dafora in the 1930’s. Moments like these reinforce the idea of an ”African cultural continuum” set forth by the art historian Richard Powell.

For a pure dance high, there is Primus’s forceful amalgam of African and modern dance accompanied by African drummers, Eleo Pomare’s alarming portrayal of a junkie with the shakes in ”Blues for the Jungle” (1966), Blondell Cummings’s feisty gesturing in a television adaptation of ”Chicken Soup” (1988) and Mr. McKayle’s and Ron Brown’s individual versions of the rumba, seen in a rehearsal of their collaboration, ”Children of the Passage” (1998). Other gems are clips of the young Alvin Ailey with Carmen de Lavallade in a duet by Lester Horton; Mr. Jones and Arnie Zane giddily bouncing off each other’s energy; Gary Harris’s spiraling arms and percussive chest in a reconstruction of Dafora’s ”Ostrich Dance” (1932) (click here for an excerpt of Ronald K. Brown performing this dance); Tommy Gomez (unidentified in the film) coiling fiercely in Ms. Dunham’s ”Shango” (1945); and Maia Claire Garrison’s tough pelvic moves in Jawole Willa Jo Zollar’s ”Batty Moves” (1995). The documentary also includes stirring clips from Talley Beatty, Garth Fagan and Ulysses Dove.

Missing are Black dancers who did not choreograph but who left their marks. Who could forget Mary Hinkson, who brought her etched lines and womanly power to Martha Graham’s roles? Or Carolyn Adams, who infused Paul Taylor’s dances with a joyous buoyancy over a 20-year period? What was their influence on the white choreographers they danced for? And what about Syvilla Fort (seen fleetingly in a ”Stormy Weather” excerpt), the Dunham principal who led her thriving school? Also missing are many of the Black choreographers who have emerged in the last 10 or 15 years. Another frustration for the curious: some of the footage is not identified.

But these are quibbles. The result of a 10-year project initiated by Gerald Myers of American Dance Festival, ”Free to Dance” is a gift to modern dance and a moving addition to the field of cultural studies. By showing a glimpse of the mighty contributions of Black choreographers, the program, produced and directed by Madison Lacy, questions the accepted notion that modern dance was launched by the four white ”pioneers” Martha Graham, Doris Humphrey, Charles Weidman and Hanya Holm. Certainly Katherine Dunham and perhaps Pearl Primus could be added to that list of elders. Anyone interested in dance as an art will savor every minute of this ambitious and illuminating program.

Historical Essays 3

Thank you for reminding us of these wonderful contributions that enhance our understanding of Black dance artistry in the 20th century.

Thanks for your comment. Some of the sections of Free to Dance are on YouTube.

Yes. I have often shared excerpts from the series with students and now since they have become available on youtube, I have linked them as resources in curricular materials I created for the Ailey organization and Dance Theatre of Harlem.