As a young dancer with recurring back spasms, I sought relief with various physical therapies. Around 1971, Sandra Neels, a longtime Merce Cunningham dancer, told me about Elaine Summers’ approach to somatic healing. Teaching only a few people at a time, Elaine would pay deep attention to our physical tendencies and give us time to sprawl out on the floor, with rubber balls placed underneath areas of tension or pain. With her pleasant face and gentle voice, she could almost talk our clenched muscles into letting go. She was always delighted by our discoveries about our own body holdings. When I started dancing with Trisha Brown in 1975, I was happy to see that she used the balls also. Trisha once told me that one of the reasons she invited me into her company was that she knew I’d studied with Elaine. Only later did I learn of Elaine’s artistic innovations. And only after digging into this research did I realize how much her multi-faceted work influenced the trajectory of the groundbreaking Judson Dance Theater.

“You should not make an effort to ‘see,’ but to let everything flow to you. I feel the choreographer and the dancers are having [a] conversation with the audience.” —Elaine Summers [1]

Elaine Summers was a founding member of Judson Dance Theater, the historic band of renegades that re-routed modern dance into post-modern dance. But she did not make her name as a choreographer like her peers Yvonne Rainer, Trisha Brown, and Lucinda Childs. Rather, she became a leader in somatic practice while also becoming a key player in the new field of Intermedia (investigating the space between defined media) Her healing system, Kinetic Awareness, which uses rubber balls to target tension, is used by many dancers today, usually in diluted form. She also one of the first to combine experimental film and dance. In everything she did, she applied John Cage’s principles of art and life being inextricable and of chance as a method of composing. Her enduring contributions to the dance and art worlds were filmdance (where film and dance are necessary to each other), Intermedia, and Kinetic Awareness. To these three, I would add a fourth: Summers actively brought people of color into the Judson fold of early post-modern dance.

Summers was born in Perth, Australia, as Lillian Elaine Smithers. The family moved to Boston when Elaine was 5, and she started begging for dance lessons at 6. While she was attending the Academy of the Assumption in Wellesley Hills, one of the nuns teamed up with the janitor to teach an Irish jig—a memorable treat for the young Elaine. She went on to ballet lessons at Miss Hall’s School in Pittsfield, where she encountered Senia and Regina Russakoff. This married couple had been Russian ballet dancers in Saint Petersburg; Senia had performed in Pavlova’s company and also on the American Vaudeville circuit. Because her parents did not support her dance fervor in any way, Elaine earned the money for classes by babysitting and selling hats on weekends. Nor did her mother encourage her to go to college, but two good friends urged her to apply to the Massachusetts School of Art (now the Massachusetts College of Art and Design). There she encountered a teacher who was important to her—Priscilla Nye. Nye believed that everyone has uniqueness within them, an idea that became a cornerstone of Kinetic Awareness. Nye also introduced Elaine to the teachings of psychologist Carl Jung.[2]

After graduating with a degree in art education in 1947, Elaine married a student named Warren (sometimes Dan) Spaulding, who was going to school on the G.I. bill. The couple moved to St. Louis, where she taught art and continued taking ballet lessons. In the summer of 1952 she went to Alfred University to take an advanced ceramics course. There she met visual artist Carol Summers, who became her second husband. They came to New York, where Summers studied at the Martha Graham school and then attended Juilliard as an extension (non-credit) student. There, she took ballet with Antony Tudor, modern dance with members of the Martha Graham Dance Company (mostly Yuriko), and composition with Louis Horst.[3] Among her classmates were the choreographer Paul Taylor, the exquisite Cunningham dancer Carolyn Brown, and Donya Feuer, who later collaborated with Paul Sanasardo. She studied with dance artists outside of Juilliard too, most notably Janet Collins, who, in 1951, became the first Black ballerina to perform at the Metropolitan Opera House. Collins had been in Lester Horton’s company in Los Angeles. Her technique was equally dazzling in modern dance and ballet, inspiring younger Black dancers including her cousin, Carmen de Lavallade, and Alvin Ailey. In 1949, Dance Magazine named Collins “The Most Outstanding Debutante of the Season.”[4] Collins headed a short-lived touring company in the mid-50s that included Elaine. According to Summers’ friend Daryl Chin, it was her experience with Collins that gave her the awareness that a dance company could/should be racially integrated.[5]

While training intensively at Juilliard, Summers developed osteoarthritis in her right hip—“sheer agony,” she said.[6] She told her psychotherapist, a Jungian named Renée Nell, about a dream she had of being able to dance pain-free. Nell suggested she consult with Charlotte Selver, a disciple of Elsa Gindler.[7] A leader of somatic practice or “physical re-education” in Germany, Gindler countered the mechanistic nature of traditional calisthenics by encouraging students to shed their habits of tension. She guided them to investigate movement with a sense of discovery, bringing consciousness to the “experiments.”[8] For Summers, learning Gindler’s approach was “revolutionary to me…It was especially difficult for me to give up cultural body images and the ballet dancer’s body image.”[9]

After two years with Selver, Elaine studied with Carola Speads, another Gindler master student, for about five years. (Both Speads and Selver, being Jewish, had fled Germany.) About her first class with Speads, Summers said, “Satori! I realized I was a dancer but didn’t know anything about the body except what to tell it to do.”[10] From Speads, she learned to slow down and listen to the body, to be aware of “how our body loves to move… to feel the deliciousness of being in touch with all the senses of our kinetic self.”[11] To understand Selver and Speads’ work in context, she started reading books like Mary Ellsworth Todd’s The Thinking Body (1937) and Wilhelm Reich’s Character Analysis (1933), in which he introduced the concept of body armor.

When speaking about Selver (who was a Buddhist), or Speads, Summers could wax mystical: “Those teachers are part of this wonderful underlying overhead magic that there is more than we can see, but the evidence is there. I love the idea that what we do as teachers and artists is we make evident the invisible.” [12]

In developing her own healing system of Kinetic Awareness, Summers combined the subjective experience of sensing the body with an “objective” knowledge of anatomy and physiology. “I would read anatomy as if it was candy,” she recalled.[13] Her goal, as quoted by her disciple Ellen Saltonstall, was “to move every part of the body all the ways it can go, easily, any time you want, with as much or as little tension as you want, at any speed.”[14] Thomas Körtvélyessy, who manages the Elaine Summers Dance and Film site, says, that KA has been “a tool for training our bodies, enabling us to also incorporate teachings from other kinds in a very safe, self-empowered way.”

Summers never promoted one way as the way. As dancer/choreographer Juliette Mapp remembers, Elaine was open to other sources of information. She wanted the students to collect their own array of sources, to follow their curiosity.[15]

During the late ’50s, she continued taking and teaching dance classes. She was studying with modern dance heavies like Mary Anthony (she liked the breathing exercises) and Don Redlich (for his attention to alignment). She took Merce Cunningham’s classes, including his weekend workshops in repertory. In her own teaching gigs, she encountered widely divergent student bodies. At the Hawthorne School in Westchester County (probably the Hawthorne Cedar Knolls School, which shut down in 2018), she was dealing with students plagued by mental health and substance abuse issues, while at a school in Roslyn, Long Island, the students were from privileged families. With her eternally curious nature, she absorbed all of the problems and learned from them.

In 1959, at Haystack Mountain, an experimental School of Crafts in Maine, she met avant-garde filmmaker Stan VanDerBeek, who had been at Black Mountain College when Merce Cunningham and John Cage were bubbling up with different ways of organizing performance. He experimented with collage and with creating immersive film environments, both modes that can be seen in Summers’ later work. Also that summer, Elaine recalled, “Somebody was giving a talk about John Cage’s chance method, which I, of course, thought was really ridiculous.”[16] (Needless to say, she reversed her opinion with what came next.)

In the fall of 1960, Robert Dunn, at the bidding of John Cage, offered classes in dance composition at Merce Cunningham’s studio in the Chelsea neighborhood. Among the first five students were Yvonne Rainer, Steve Paxton, and Simone Forti. Word spread. To understand Dunn’s approach and how fertile it was, I offer these thoughts from Dunn himself, which he wrote while looking back twenty years later:

My general attitude in teaching was influenced by several somewhat disparate factions. I was impressed by what I had come to know of Bauhaus education in the arts, particularly from the writings of Moholy-Nagy, in its emphasis on the nature of the materials and on basic structural elements. Association with John Cage had led to the project of constantly extending perceptive boundaries and contexts. From Heidegger, Sartre, Far Eastern Buddhism, and Taoism, in some personal amalgam, I had the notion in teaching of making a ‘clearing’, a sort of ‘space of nothing,’ in which things could appear and grow in their own nature. Before each class, I made the attempt to attain this state of mind, with varying success of course…[17]

At that time, when young dancers perceived Graham’s emotionality and Limón’s noble groundedness as old hat, Dunn’s approach opened up a fresh avenue of creativity. Students felt freed by Dunn’s openness and lack of judgment. Instead of declaring whether a study was good or bad, he would ask the students, “What did you see?”[18]

Summers had just started experimenting in film with VanDerBeek. For her, film was a logical outgrowth of dance: “Exploration of light and movement naturally led me to filmmaking. Film to me is another form of dance: Camera movement and editing are another form of choreography.” She felt that film gives the eyes a certain power. When interviewed by Tony Carruthers of the Bennington College Judson Project, she said, “Film gives you as the audience, or you as the choreographer, wild eyes, like an animal that can come up to you [going right up to Carruther’s face] and see your whiskers in your beard.”[19]

She was also entranced by the light of a film projector. “What’s magical about film is that … you don’t see [its light] until an object goes in front of it…a floating image you don’t see until you put your arm through it.”[20] She started shooting pedestrian traffic and manipulating the footage—changing the speed, the angle, the framing. “Filmmaking allows me to exploit the motion within the image and edit the film as if it were a dancer.”[21]

By the time Summers enrolled in Bob Dunn’s classes, the roster included Trisha Brown, Lucinda Childs, Ruth Emerson, Deborah Hay, and others. The assignments were not only chance procedures, but other approaches too, like Make a Dadaist cut-up, where you cut up something old to make something new, or, Do a dance that is stripped down to utter simplicity—“one thing.”[22]

Dunn encouraged students to value the ordinary, rather than dressing things up to be fancier or more “interesting” than necessary. They were going for natural movement, rather than trained or stylized movement. Part of the rebelliousness of Judson Dance Theater was they didn’t want to “reassure the audience”—Summers’ words—that they would provide the conventions of professionalism.[23] Shedding ballet mannerisms, which was a goal in the sensory awareness work, was also a goal at Judson. Using chance mechanisms, like rolling the dice and making a chart of corresponding actions, helped make that happen. You might be assigned to move a body part in a way you’ve never done before. For Summers, “It was an expansion of how you thought about dance and ways of structuring dances that would help open the prison of your mind.”[24]

Summers remembers the feedback for her first dance, which she had made as part of a film project:

I was working on my first film with Eugene Friedman and I made a dance for it based on the legend of Ondine. Steve Paxton said very kindly—not unkindly—to me, “Well, I didn’t like that much,” … It was my first dance. I got puzzled, so I went home and thought about how I could change it. I thought: I like it, and I like what I’m thinking about in this piece. So, I did it again—fixing a little but not much. When I finished, Steve said, “Well, I don’t like the dance any better, but you sure danced the hell out of it.” Wasn’t that a lovely thing to say?[25]

Elaine, having been involved in Christian Science growing up, always put a positive spin on things.[26] Paxton, on the other hand, made it his practice to dispense with the veneer of societal decorum.

Summers appreciated the environment that Bob Dunn fostered: “How could a man of such a gentle elusive presence be so direct, cutting to the core of our imaginations? Explaining, lighting pathways, with no effort to control, only to expand our consciousness.”[27] In terms of the Cage-inspired method Dunn was teaching, she connected it to her arts training at Mass College: “He was teaching us the chance method, an extraordinary teaching method. It makes you lay out in front of you all of the elements—what is possible for you to choose from. I had art school training, where you tried to deal with elements, the Bauhaus tradition. If you were dealing with ceramics, you tried to deal with the clay itself. With all creative work, you need to understand the elements.”[28]

After about a year and a half, the students felt they had enough work to show to the public. (The Cunningham studio was on the top floor of a building owned by the Living Theatre, so they occasionally showed their work downstairs in that studio. But it was a small space and they needed something larger, though still intimate.) For more on how they auditioned for the 92nd Street YM-YWHA—the 20th century’s bastion of modern dance—and how they arrived at Judson Memorial Church, see my account of all that.

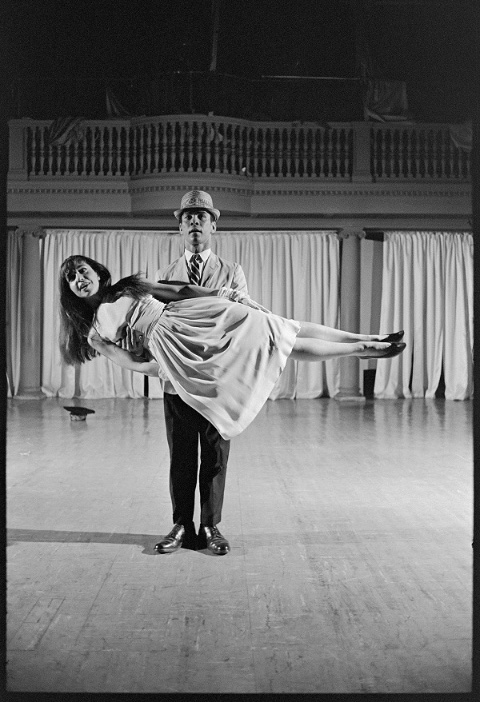

Contact sheet of photo shoot, c. 1962, of Elaine with Rudy Perez, the beginnings of Take Your Alligator With You, found on Rudy Perez Dance, gift of Elaine Summers, photographer unknown.

The church gave the young dancers performance space, rehearsal space, and help with mailings. Summers felt like the Church was giving them a grant, and the icing on the cake was their emotional support. (It seemed to Elaine that Carmines and Moody actually liked the dances.) For the first concert, held on July 6, 1962, the fourteen participating dance artists created twenty-three pieces, and Dunn oversaw the whole sequence.

The opening number on that first evening, “A Concert of Dance” (later named Concert #1), was not actually a dance. It was Elaine’s film collaboration with composer John Herbert McDowell and filmmaker Eugene Friedman. Titled Overture, it tossed together 16 mm images that McDowell had collected from old W. C. Fields films with footage Friedman and Summers had shot. “We put bits and pieces of film in a brown paper bag and used a telephone book as a ‘chance’ mechanism.”[29] The film collage was projected onto a curtain that the audience had to walk through in order to get to their seats. Dance scholar Sally Banes observed, “So from the moment the concert started, the irreverent trespassing of artistic boundaries was present.”[30]

The New York Times critic Allen Hughes wrote that “The overture was perhaps the key to the success of the evening, for through its random juxtaposition of unrelated subjects—children playing, trucks parked under the West Side Highway, W. C. Fields, and so on—the audience was quickly transported out of the everyday world where events are supposed to be governed by logic, even if they are not.”[31]

Also on the program were two live dances by Summers. The first, Instant Chance, was a loving, though possibly too-cute, spoof of the chance method. Noticing that sometimes a chance score was hidden, or not legible, Summers wanted to make her score really obvious. The seven dancers threw bulky foam “dice” into the air, each one about the size of a beachball, and when they landed the dancers would get their cues for what task to do. The color determined the speed and the number governed the rhythm—say a 2/4 or a waltz. Later iterations included options of types of actions, for example tensing, or swinging, or rippling.[32] For the second, The Daily Wake, Summers used the front page of The Daily News as a map for the dance. She taught the dancers (including one non-dancer, the composer John Herbert McDowell) positions she saw in the paper. These included “swimming, an umpire, soldiers, a handshake, Rockefeller, a bride, graduation, and a Panino advertisement.”[33] She also gave them numbered phrases and a floor pattern similar to a newspaper layout.

Other choreographers that first night included Yvonne Rainer, Steve Paxton, Ruth Emerson, David Gordon, Fred Herko, and Deborah Hay. It was a long program, but the choreographers, dancers, and the audience, who had crammed into the church in ninety-degree heat, felt it was the beginning of something new. In her memoir, Feelings Are Facts, Rainer described the elation:

We were all wildly ecstatic afterward. As the audience enthusiastically applauded at the end, I clasped Judy [Dunn] around the waist, hoisted her in the air as we both exclaimed, “It’s a positive alternative!” The church would become our home, its basement gymnasium available for weekly workshops and additional performance space, an alternative to once-a-year hire-a hall mode of operating that had plagued the struggling modern dance before. Here we could present things more frequently, more cheaply, and—most important of all—more cooperatively.[34]

The high after that first concert generated energy for the next two years. Elaine had been teaching at the Turnau Opera House in Woodstock, New York, and she decided to bring a bunch of her dance pals up there for “Another Concert of Dance” (later called Concert #2). This concert comprised Overture, The Daily Wake, and works by Ruth Emerson, Liz Keen (a Paul Taylor dancer whom Elaine met in Speads’ class), and Summers’ new Suite. This last was a takeoff on Louis Horst’s course in Pre-classic Forms, which he developed in the 1930s in order to impose structure on the messy new genre of modern dance. She followed his format, choosing as her pre-Classic dances the Galliard and the Saraband—and the Twist. It was a brilliant decision to claim a current social dance as a hallowed court dance, thereby democratizing the forms. To further democratize, she invited the audience to twist along with the dancers.[35]

Theatre Piece for Chairs and Ladders, 1960s, with Al Hansen and Phoebe Neville. Ph Terry Schutté in Dance Magazine

Dunn taught the weekly sessions for two years, sometimes assisted by his wife Judith (Goldsmith) Dunn, who was a dancer in Cunningham’s company. Then there was a hiatus, during which the students continued workshops and discussions in Yvonne Rainer’s new loft.[36] When the basement of Judson Church became available on Monday nights, they held workshops there. At that point, Dunn dropped out as a teacher and the group was on its own. Now a leaderless collective, they adopted Ruth Emerson’s suggestion of making decisions by consensus, Quaker-style.

The democracy of the feedback sessions appealed to Summers: “One of the rules was that there was no president. We were all equal and we sat in a circle.”[37] She described how each week a different person was responsible for the method of critiquing. During Paxton’s week as facilitator, she recalled, “Steve said, ‘You may each say one thing you actually saw take place in the dance and it will be one sentence long and that’s it.’ ”[38]

Although Summers had been developing Kinetic Awareness since the 1950s, it wasn’t until Concert #6, in June 1963, that she made a dance based on her practice. In Dance for Carola, she simply moved from standing to squatting—taking almost ten minutes to do it. Carola Speads had taught her the benefits of slow motion, and Dunn had given the assignment of “one thing.” Summers thought her colleagues would hate it, but they surprised her with their enthusiasm. Rudy Perez, who had danced duets with her, sighed, “Ah, that is so beautiful.”[39] He said he liked it so much it could have gone on longer. (In another interview, she said Rudy was jumping up and down.[40]) When Perez created his extraordinary solo, Countdown (1966), in which he rose from a chair in slow motion to the Songs of the Auvergne, he may well have been influenced by Summers’ slow-motion Dance for Carola. (The haunting Countdown was later performed by the Ailey company—probably the only Judson dance ever taken into a major company’s rep.)

Summers asked Bob Dunn to create music for a dance she was making during the summer of 1963, when four Judson performances were held at Gramercy Arts Theater. (These concerts, #9–#12, were also organized by Elaine.) Treating the theater a site-specific opportunity, she made a piece about entrances and exits, with dancers entering from the audience, from a trap door, or from a ladder connecting a side balcony to the stage. Dunn decided that the music would be lines from Oscar Wilde’s plays, spoken by the dancers. The title, Country Dances, came from one of these lines. For a trio section in which one woman, held in the air by two men, her feet never touching the ground, was saying lines like “Love changes one.” Her brazen exploration of the theater spaces, plus the chance element of Dunn’s “music” created a certain frisson. John Herbert McDowell remembered that “there was a lot that happened up in the air. Ruth Emerson saying something about German grammar while hanging from the ceiling.”[41] (In journalist McDonagh’s memory, she was hanging upside down.[42])

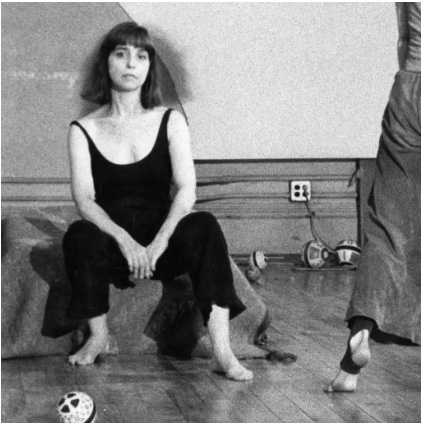

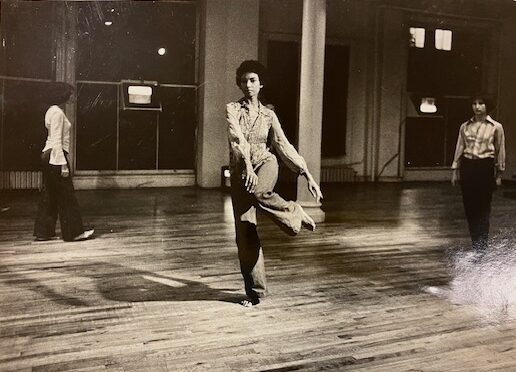

Fantastic Gardens,1964. From left: Sally Gross, Carla Blanc, Tony Holder, Ruth Emerson, Sandra Neels. Ph Dan Budnik.

Short pieces were the order of the day at Judson. The idea was to experiment, not to make a masterpiece. However, Summers spent three years planning for her evening-length Fantastic Gardens (1964), combining dance, film, sculpture, and music‑—and mirrors. (Until that point, the only other single-choreographer evening at Judson had been Yvonne Rainer’s Terrain in 1963.) The everything-at-once extravaganza deployed sixteen dancers, two composers, five visual artists, eight 16-mm projectors, four Super-8s, three projectionists, five photographers, and a tree made of metallic junk. She wanted to spell out the non-hierarchical relationship was between choreographer and dancers, so she wrote on the program notes, “Elaine Summers is the choreographer of the dances. She has provided the dancers with a framework—movement scores—within which they are able to improvise, as individual dancers.”[43] Among the photographers was Billy Linich, who was also painting everything silver at Andy Warhol’s Factory.[44] More than a year in advance, Elaine asked Sarah Stackhouse, a beautifully expressive member of the Limón company, to dance in a film that would appear next to her dancing life. In Fantastic Gardens, Stackhouse danced in front of the film to create a meshing of live and filmed body parts.

Summers was delighted when the audience took her mirror idea and ran with it:

We gave the audience little tiny mirrors. I had discovered if you put a mirror at the lens of a projector and you move the mirror, you…can move the image.…The film projector was on the floor. They were supposed to…use the mirrors to light the way to their seats. Then they caught on, and they started signaling each other across the space, which was absolutely gorgeous.[45]

This was a typical reaction of Elaine’s. She loved when a chance occurrence opened the possibility for something else to happen. Another example was when she noticed that the apartment across from hers had a neat row of garbage cans out on the fire escape, which gave her the idea of watering the cans to become a “fantastic garden.” She created a recurring story within the otherwise random collage of film. It involved Fred Herko, a trained ballet dancer (with a face that is eerily reminiscent of Rudolf Nureyev’s) periodically emerging from that apartment to water the garbage cans as if they were a garden. He was clothed differently each time—jeans, a fur coat, a bikini. Finally, with the last watering, a bunch of huge plastic plants popped out of the cans. Springtime in a fantastic garden!

Jonas Mekas, the Village Voice film critic and experimental filmmaker, raved about the performance:

Fantastic effects were produced by using a split screen, a screen made of several dangling strips of white material which moved and separated, and there were human figures appearing through the partings, moving into and out of the screen, submerging, disappearing into it, participating in it, so that at times one didn’t know…what was the photograph and what was the real live presence. Actions of images overlapped or repeated or extended actions of dancers and people—the same figures, often, appearing on the screen as in the dance arena or around the balcony.

All this worked as an artistic unity…there was an attempt here made to produce an aesthetic, soul experience consisting of a variety of feelings, motions, and emotions. It came close to an audiovisual-spatial symphony that moved us and involved us in strange and beautiful ways, new ways, never before experienced ways, something that contained amazement and glimpses of not yet familiar beauty.[46]

With multiple projectors, the filmed images spilled out onto the walls, ceiling, and floor. There was so much going on that one couldn’t possibly see or hear it all. Jill Johnston, the Village Voice dance critic at the time, got into the groove: “Not straining to get it all, one could bask in the total atmosphere, which was off-beat and romantic, like an elegant garden party gone somewhat haywire… Miss Summers’ mélange was an unusual and provocative affair.”[47] Years later, Jennifer Krasinski, an editor at Artforum, called Fantastic Gardens “a watershed moment in the evolution of intermedia art.”[48]

One of the people influenced by Fantastic Gardens was Trisha Brown, who later became perhaps the most well-known American post-modern choreographer. She had been studying with Elaine and the two were close friends. Trisha not only absorbed Elaine’s teachings about body awareness as a lifelong practice, she also admired Elaine’s techno experiments. Two years after Fantastic Gardens, Trisha created, Homemade (1966), a solo for which she wore a projector on her back, the encumbrance being a collaboration with theater artist Robert Whitman. Her movement splashed the filmed images all over the house—the walls, ceiling, floor, and audience. As art historian Susan Rosenberg has pointed out, Homemade had a lot in common with the Fantastic Garden’s mode of images spilling out everywhere.[49] In fact, I would wager that Brown’s famous series of equipment pieces (1968–1974) might not have happened if she hadn’t witnessed Summers’ experiments.

The cross stimulation that happened at Judson is something Summers particularly enjoyed. Another example: Summers was amused when she saw Paxton’s Flat (1964), in which he disrobed and hung garments, one by one, on hooks that he had affixed to his skin. It made her think about “our bodies as holders of clothing”—and about technology:

I made a dance called To Steve With Love, where people were actually dressing and undressing and had little speakers. One had a speaker on her forehead, another on his belly button, and another had a radio beside him because I was also intrigued with the coming of the portable radios. We were all playing with media. Like Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers, dancing [with] music in the park, now everyone could have a full orchestra when they danced in the park.[50]

She was ahead of her time. Now, of course, most Broadway performers wear tiny microphones on their foreheads. Summers was always thinking of ways that dance could partner with technology.

The term Intermedia was popularized by Dick Higgins, who, like Robert Dunn, had been a student in John Cage’s famous course in Experimental Music at the New School. That course blew open existing definitions of the separate disciplines. In his first Intermedia newsletter, Higgins declared, “Much of the best work being produced today seem to fall between media.”[51]

Embracing the term, Summers formed the Experimental Intermedia Foundation in 1968. It provided organizational support for her own productions as well as those of others genre-defying artists including Trisha Brown, composers Malcom Goldstein, Philip Corner, Carman Moore, and composer/filmmaker Phill Niblock, who took the helm in 1985.[52]

One of Summers’ first productions under EIF was the three-hour version of Energy Changes at the Museum of Modern Art in 1973. The dance traveled through several stages that started very small internal movements and gradually worked up to a commotion of interaction—as slow as Dance for Carola. Corner had hung objects like cymbals and gongs along the path for the audience to play with. Summers had given the audience instructions, asking them to stand near one dancer and quietly move to another dancer. Don McDonagh of the New York Times found the prolonged event pleasant but underwhelming: “The only problem was that the movement invention did not sustain constant interest. Perhaps it was not meant to.”[53]

To the point. One wonders how rambling Summers intended it to be. Her purpose was certainly not to produce a good artwork. Perhaps, like Kinetic Awareness, the idea was to look at the inner and outer landscape with fresh eyes. She would probably agree with her collaborator, the composer Pauline Oliveros, who has said, “I have never tried to build a career. I’ve only tried to build a community.”[54]

Undaunted by middling reviews, Summers organized the first Intermedia Arts Festival in 1980. The schedule of eight performances at the Guggenheim Museum was augmented by seminars, workshops and an international symposium at other venues. It was a way to extend the 1960s fervor for defying categorization. The artists included Summers, Higgins, Allan Kaprow, Kenneth King, Joan Jonas, Meredith Monk, Ping Chong, and Nam June Paik, the “father of video art.”

LIVE Performance Art magazine (an offshoot of Performing Arts Journal), celebrated the ten-day series by printing statements from some of the artists. Elaine used her space to say that women had not been recognized for their role in this pioneering field. Dick Higgins, pointing to forms that erupted in the 1960s such as “visual poetry” and “happenings,” asked, “Between what two media does this work lie?” Joan Jonas, one of the few women who achieved prominence in the field, wrote that, “the desire to move suddenly from one space to the next, continuously breaking the spell (illusion)” allowed her to create alternative identities. Kenneth King, who called his dance-and-text pieces “transmedia,” predicted that “the computer will be able to deal with many different channels or tracks of information simultaneously.” (Remarkably, King had been predicting the centrality of the computer since 1974 with his piece The Telaxic Synapsulator—which I danced in.) Meredith Monk wrote, “By placing one thing against or with another makes each element become more mysterious and the whole more luminous.” Allan Kaprow, the “father of happenings,” dismissed the term intermedia as nostalgic.[55]

Not included in this compendium of definers was Hans Breder, who had left New York in 1966 for a job at the University of Iowa. Determined to replicate the downtown ethos of defying boundaries, he started an Intermedia program in Iowa City. Breder defined intermedia “not as an interdisciplinary fusing of different fields into one, but as a constant collision of concepts and disciplines.”[56] (Among his most famous students were Ana Mendieta and Charles Ray.) He was important to Summers in that he invited her for residencies and made space avaiable to her, specifically a large loft with a ladder in it. And his students were available to her for some of her films. This included the captivating, dreamlike Iowa Blizzard (1973), where clusters of black-clad students are tromping through the snow. On closer inspection, one sees that each cluster is actually one person with overlays—a four-way superimposition that Breder’s students, with Summers’ encouragement, came up with in the lab.[57]

During that first Intermedia festival at the Guggenheim, Summers premiered Crow’s Nest, a collaboration with avant-garde composer Pauline Oliveros, who had studied with her. What Oliveros and Summers shared was an idea of deep listening and a love of nature. Sites that were captured by Summers’ camera included Lake Placid, Jupiter Island, and Joshua Tree, making for a beautifully lush two-dimensional environment—which appeared three-dimensional because fluttering strips of white fabric created an environment that dancers could enter. For Alexandra Ogsbury, longtime Summers dancer in the ’70s and ’80s, Crow’s Nest was her favorite piece to perform. “It really came together in terms of all the different things she had been experimenting with. The dancers moving in and out of the silk panels, I thought was brilliant.”[58] Crow’s Nest actually started, unofficially, in Summers’ loft in 1979, then went to the piazzas of Italy before reaching the Guggenheim. It was later repeated at the Hunter Museum in Tennessee in 1998 and again in Boston’s Cyber Festival in 2006.

Another work that relied on the visuals was Solitary Geography, a large piece specifically for the Performing Garage in 1983. (Solitary Geography began as a dancefilm solo in 1977.) The Village Voice critic Deborah Jowitt described the extraordinary performers Min Tanaka and Suzushi Hanayagi, but felt the overall action was formless. Instead of condemning it, however, she drew on her past insights about Summers to say, “If this piece is about anything, it’s about Summers’ love of kinetic images in inanimate nature and the power that resides in sensitive human movers.” New York Times critic Jack Anderson praised Pepón Osório’s set that suggested a natural landscape, Jon Gibson’s music that also hinted at nature, and the overall “harmonious mingling of art forms.” The only choreography he commented on was when Min Tanaka “crossed the stage on a sputtering motorcycle.”[59]

In 1984, Summers returned to the Guggenheim for the Second Intermedia Festival, with Skydance/Skytime, which continued the open-air event Skydance from 1982, again collaborating with German artist Otto Piene. A huge red flower atop the museum’s roof alerted tourists that something funny or absurdist was going on. Indoors, Carman Moore’s ensemble of musicians, complete with a gong and wind sounds, played as another Piene contraption—a large snaky inflatable—puffed up, uncoiled, and rose upward. But the hooks and wires kept getting stuck along the way and had to be hurriedly fixed by a team of workers. Jowitt wrote that the performance had an “aura of magic that no technical hitches dispel.”[60] Jennifer Dunning went so far as to call the technical crew the “real heroes of the evening.”[61]

Meanwhile, Summers work as a somatic teacher continued to deepen. To give an idea of how her approach could help heal the whole person, I quote Merián Soto, a notable dance artist who studied and danced with Summers from 1978 to 1983:

“In my memories of Elaine, she is a guide leading her students toward inner realms, where, like archaeologists on a dig, we explore in fine detail the mysteries of our bodies. In her role as guide, she is free of all agendas save a generous, listening presence. She exudes a deep respect for our uniqueness as individuals, sitting beside and supporting us as we delve into the aliveness of our moving bodies. Through her words and quality of presence, she guides us in a practice of noticing: our emotions, memories, and the evolution of ideas within our flesh…I trusted her completely, and because of this, I learned to trust the truth of my body, senses, and movement…. as a Puerto Rican woman …I was on a quest to decolonize my body/mind/psyche from assumptions and patterns…of thinking, being, and moving that blocked inner knowledge.”[62]

Summers’ interest in body awareness and her interest in choreography started to flow into one river. Advanced students like Soto became her dancers. As they were concentrating on breaking habits to free their bodies, they were also developing ways to participate in Summers’ spectacles. One of the scores she gave, according to former student and current multi-media dance artist Frances Becker, was “1 + 1 + 1 + 1,” which meant you could never repeat a movement but always had to come up with new movement.Becker explained this score in an article in CQ Unbound. [63] In both chance procedures and Kinetic Awareness, the goal was to expand consciousness.

To give you an idea of how KA could consume time, Becker tells of her first visit to a KA class in 1978: “Elaine very cheerfully told me to lie down and take 45 minutes to warm up and then take half an hour to stand up. She would come and see who made it up in time. She disappeared behind a door.”[64] Becker then proceeded to spend five years studying with Elaine before being asked into her company.

While entering into Kinetic Awareness with Summers was a rich, transformative experience, being involved in rehearsals could be frustrating. About working with her on The Illuminated Workingman in the ’70s, Soto wrote, “While Elaine was wildly enthusiastic, her process was chaotic. She would change unison movement for a large group section moments before the show, leaving dancers confused and unable to achieve the intended unison. But it was enormously fun.”[65]

What wasn’t fun, as I’ve hinted, was the sexism in the art world. Summers felt women were under appreciated in the field of Intermedia, and that she had to ignore “the ‘put-downs’ women often experience in the male-dominated world of technology.”[66] Men like Dick Higgins, who had his own printing press, seemed all powerful, making her feel that “I didn’t have a chance.” Summers also talked about psychological demons, like the inner critic demanding that you raise your leg higher or tighten the structure of your choreography. “Unconsciously in your mind, those demons are nibbling away at you and you’re quietly trying to do the dance that you have to do and be in touch with yourself.”[67] She was aware, too, of another set of demons, specifically about our bodies. In a profile in Ms. Magazine, she said, “I want to get rid of the built-in criticism about our bodies that we all carry around with us, the accumulations of negative body attitudes and tensions that are no longer appropriate.”[68]

Rehearsal for Illuminated Workingman in Buffalo. Elaine at right, Robert Coe in center. Found in clipping file, Jerome Robbins Dance Collection, Library for the Performing Arts.

Yet she always presented an optimistic picture. Playwright and journalist Robert Coe, who performed in The Illuminated Workingman (1979) in Buffalo, likened Summers to a “buoyant innocent kindergarten teacher.”[69] The language she used to describe her work was often cheerful. Mapp recalls a flyer posted on Summers’ door with a schedule for weekly classes. The first week focused on “Your Fabulous Head and Neck,” the second week on “Your Great Shoulders & Arms & Hands,” the third week on “Understanding Your Incredible Spine,” and so forth.[70] While Mapp was charmed by this cheerful language, she sensed it would lead to a deeper mission.

Ogsbury, who danced with Summers from around 1969 to 1984, felt by the end of that period, that there was a disconnect between what she called the “flamboyant” language, which she felt was “unreal,” and the actual work of Kinetic Awareness, which she called “real, real, real.”[71] And Summers wasn’t always so sweet and flowery. Coe had this memory: “Elaine had a laugh that came in soft bursts, and she was always smiling, but just as The Illuminated Workingman was ending that last night in Buffalo, she got into one of the greatest angry screaming matches I have ever been privileged to witness. Elaine literally got nose to nose and toe to toe with one of the dancers she had brought in from New York.”

Although Summers did not write a lot—except for endless grant applications—she sometimes use language that revealed her observational powers. This is clear in her descriptions of a few of her students who became prominent dance artists.

Each dancer is an entire universe. I think of Suzushi Hanayagi, whose dance energy and imagination is powerful, intense and daring. She seems a samurai warrior let loose. Dana Reitz who is a laser beam of sheer LIGHT. Eva Karczag, a vertical brook, she contains all the possibilities of white water rapids, and still pools. Then there is the hummingbird vibration of Min Tanaka’s high tension, and Trisha Brown’s silky ambiguity and complete innocence concerning the existence of gravity.[72]

This generosity of spirit cut across racial lines too. Summers was “ahead of her time” in that she was a white woman who actively sought out people of color as dancers, musicians, collaborators. Her experience with Janet Collins in the 1950s brought into focus how important it is that Black people and other non-whites have opportunities. She hired and/or nurtured a number of artists of color at different points in their careers. Elaine met Rudy Perez, who was from a Puerto Rican family in the Bronx, at a studio she rented in midtown. She invited him to perform in her piece The Daily Wake on the first Judson program. Perez started making works himself, notably, the much-photographed duet for himself and Elaine called Take Your Alligator With You (1963). She also cast him in Fantastic Gardens, pairing him with Cunningham dancer Sandra Neels. He went on to become a major post-modern choreographer in New York and Los Angeles.

She hired Edward Barton (later spelled Bhartonne), who had some gymnastics training, probably after seeing him in James Waring’s ballet class (Barton is visible in the section of Judson Fragments where Waring is teaching a ballet class) or in a large piece by John Herbert McDowell, Elaine’s frequent collaborator, in Concert #6. Then in Concert #10, he performed his own spiffy novelty act, Pop No. 1 and Pop No 2, which were each about two minutes long. He simply blew up a balloon, tied it to his waist, did a back flip, and popped it when he landed. For the second edition, he landed, flipped over, and then popped the balloon. After performing in Summers’ Country Dances, he continued as a member of the Elaine Summers Film & Dance Company for years.

After Judson, Summers pulled in Pearl Bowser, whom she knew from Janet Collins’ company, to perform in her piece Dance for Lots of People (1963) at Judson Church. With Elaine’s encouragement, Bowser turned toward film. This began when Summers asked Bowser to help edit the film recording of Trisha’s Walking on the Wall.[73] Bowser became a prominent historian/curator of Black films.

In 1977, Elaine made a solo for the stunning dancer Matt Turney, who had retired from the Martha Graham’s company, for her film and performance called Windows in the Kitchen. (The film part of it is posted here.)

Summers’ most frequent collaborator was African American composer Carman Moore. He played live with his group of musicians for Energy Changes, Illuminated Workingman, and countless other projects. Moore has become a legendary artist who defies musical categories.

Summers’ commitment to diversity was one aspect of her vision of collectivity, which ultimately manifested in her many iterations of the Skydance idea. As Juliette Mapp said Summers’ last decade, “She was inspired by the Internet, the possibility for collectivity, that we’d all be looking at the sky at the same time.”[74] An early version of Skydance was produced by Hans Breder at the University of Iowa in 1982. The performance was outdoors in a meadow, with many students ferrying inflatables that shot up to the sky. Recently, with the coming of the Internet, her dream became more doable—or maybe just more dreamable:

“I want to have an ongoing web piece, artwork, that continues and pays for itself.… My dream…is to have the real whole Skytime being done all over the world all the time, continually, making money by doing the thing you want to do.”[75]

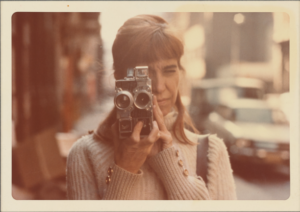

Mapp also pointed out that Summers used her camera to document the work of her peers—another form of collectivity. She shot Yvonne Rainer’s Room Service in 1963 at Judson; Steve Paxton’s Deposit (1964) in upstate New York; Trisha Brown’s Planes (1968), her first equipment piece; and Brown’s Walking on the Walls at the Whitney in 1971. It was her way of sharing, of participating in the collective, of preserving the work of her peers, so these are now valuable archives.

Video stills from Steve Paxton’s Deposit, Kutsher’s Country Club, Thompson, NY, 1965. Deborah Hay and Steve Paxton, filmed by Elaine Summers, used in “Judson Fragments” (1965). Courtesy of the heirs of Elaine Summers and the Jerome Robbins Dance Division, NY Public Library for the Performing Arts.

Elaine met video art pioneer Davidson Gigliotti, who became director of video at EIF—and her third husband. (Carol Summers had moved to California in the 1970s.) Elaine and Davidson worked on many projects together, including a stint in Florida (Elaine loved the beach) at the Sarasota Visual Art Center in the 1990s.

Summers produced many other works than those named above, with titles like Hidden Forest, Dance for Lots of People, Secret Dancers, Theatre Piece for Chairs and Ladders, and Galumphing. There were more than thirty over all, but it’s hard to count them because she recycled pieces and titles. Her influence seeped into Judson Dance Theater in both of her two main areas: Kinetic Awareness and Intermedia. In terms of the first, Judson choreographers like Trisha Brown, Yvonne Rainer, David Gordon, and Meredith Monk all studied with her. They wanted not only to heal their bodies, but they were looking for an escape from presenting the self in a theatrical way, a way that performers called “selling.” They were forging, as a collective and as individuals, a more intimate way of coexisting with the audience, sometimes inviting the audience in. What came out of this was a more interior, sensing-the-self kind of presence, animated by a more experimental attitude. And this new aesthetic opened the door for post-modern dance to walk through and thrive.

Elaine kept her creative juices going even in her last years. In 2009, Elaine Summers Dance & Film presented an evening of her films at Anthology Film Archives called “Making Rainbows.” Summers was fond of saying, “The best intermedia effect is the rainbow because it’s a combination light and water, and it exists only when those things combine in that particular way.”[76] It included films from the 1960s and ’70s like Illuminated Workingman, Walking Dance for Any Number, and Crow’s Nest. And she participated in the Danspace Project “Platform 2010: Back to New York City,” curated by Mapp. I love this quote from Elaine that appeared in the platform booklet: “Ideas are out there, waiting for someone to make them visible. The world is full of ideas. You get your instructions, but if you don’t act on them, it’s just a dream.” Included in that program was Two Girls Downtown Iowa, which showed two women rushing to greet each other on a sidewalk, shot in slow motion. Roslyn Sulcas, writing in the New York Times, called it “a remarkable conflation of kinetic effect and almost painterly moment-by-moment composition.” In the fall of 2014 Elaine’s films were shown in Berlin and Amsterdam.

Summers’ plan for Skydance was the most utopian vision of all. The last iteration of Skydance was Skytime 2014/Moon Rainbow. Presented by Solar One in Stuyvesant Cove Park, it involved Kiori Kawai as co-choreographer and dancer and two of her favorite composers—Carman Moore and Pauline Oliveros. Among the dancers was the Dutch dancer and impresario Thomas Körvélyessy, who has brought Kinetic Awareness to the Netherlands.

Screen shot of Kiori Kawaii and Thomas Körtvélyessy in an improvisation with Summers film footage, Berlin, 2023.

I conclude with a memory from dance artist Douglas Dunn, who lived in a SoHo building near Elaine’s. He recalled a moment when he saw Elaine, fallen on the street, close to where they both lived. In her 80s, she was weakened by osteoarthritis. He stopped to ask if he could help her up:

“Don’t touch me!”, with ardent fury she shrieked. There was a toughness, a profound autonomy in the tone of her screech. (There was a grit that underlay her always upbeat radiant friendliness; or, more accurately, her always upbeat radiant generous lovingness. It was impossible for me ever to be in her presence without feeling that I had been appreciating life far too little, and that I should work harder to emulate her unabashed, big-hearted joie de vivre.)[77]

¶¶¶

Special thanks to Thomas Körvélyessy, who, as executor of Summers’ estate, manages the website Elaine Summers Artistic Estate. Also thanks to Dan De Prenger and Bill Crowley, who were grad students of Hans Breder, and to Juliette Mapp.

¶¶¶

Selected Bibliography

Banes, Sally. Democracy’s Body: Judson Dance Theater, 1962–1964. Durham: Duke University Press, 1993.

Eddy, Martha. Mindful Movement: The Evolution of the Somatic arts and Conscious Action. Chicago: Intellect, 2016.

Saltonstall, Ellen. Kinetic Awareness: Discovering Your Bodymind. New York: Kinetic Awareness Center, 1988.

Notes

[1] Quoted in Anna Kisselgoff, “Elaine Summers, Who Meshed Dance and Film, Dies at 89,” New York Times, January 15, 2015.

[2] Martha Eddy, Mindful Movement: The Evolution of the Somatic arts and Conscious Action (Chicago: Intellect, 2016), 55.

[3] Elaine talked about the Juilliard training often, and her short stint as a Juilliard student is mentioned in all her biographical material. But neither her maiden name nor either of her married names shows up on the enrollment lists. The name Elaine Weil appears on the list of extension students, for the fall of 1952. She had already separated from her first husband, Warren Spaulding, and had just met her husband to be, Carol Summers, so I’m wondering if she made up a surname at random.

[4] Yaël Tamar Lewin, Night’s Dancer: The Life of Janet Collins (Middletown: Wesleyan University Press), 137.

[5] Email to author from Daryl Chin, December 20, 2014.

[6] Oral History Project Interview Transcript, 168.

[7] Ellen Saltonstall, Kinetic Awareness: Discovering Your Bodymind (New York: Kinetic Awareness Center, 1988), 16.

[8] Saltonstall, Kinetic Awareness, 19-24. By the way, a new book on Gindler, by Rebecca Loukes, has just been published.

[9] Quoted in Eddy, Mindful Movement, 57.

[10] Bennington College Judson Project interview. This Project was initiated by me and co-directed with Tony Carruthers, who conducted this interview, c. 1980. Jerome Robbins Dance Division, NYPL. “The Judson Project” NYPL Digital Collections. 1983. *MGZIDF 5872.

[11] Quoted in Eddy, Mindful Movement, 56.

[12] Eddy, Mindful Movement, 176.

[13] Eddy, Mindful Movement, 191.

[14] Quoted in Saltonstall, Kinetic Awareness, 27.

[15] Interview with the author, December 10, 2014.

[16] Oral History Project Interview Transcript, Jerome Robbins Dance Division, NY Public Library for the Performing Arts, *MGZMT 3-2626, 139.

[17] Robert Dunn, Movement Research Performance Journal #14: “The Legacy of Robert Ellis Dunn,” guest edited by Wendy Perron, 1997, originally published in Contact Quarterly, 1980.

[18] Quoted in “Why Dance in the Art World?” Performa.

[19] Bennington College Judson Project interview. Posted here by Elaine Summers Artistic Estate.

[20] Bennington College Judson Project interview.

[21] Quoted in Susan K. Berman, “Four Breakaway Choreographers,” Ms. Magazine, April 1975, 40.

[22] Sally Banes, “Choreographic Methods of the Judson Dance Theater,” Moving History/Dancing Cultures: A Dance History Reader, eds Ann Dils & Ann Copper Albright (Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press, 2001), 353.

[23] Bennington College Judson Project Interview.

[24] Bennington College Judson Project interview.

[25] Samara Davis, “Judson at 50: Elaine Summers,” Artforum online, 2012, accessed October 4, 2024.

[26] Oral History Project Interview Transcription, with Elaine Summers, MGZMT 3-2626 Pages 1-99, Jerome Robbins Dance Division, NY Public Library for the Performing Arts, 89.

[27] Elaine Summers, Movement Research Performance Journal #14, guest editor Wendy Perron, “The Legacy of Robert Ellis Dunn (1928-1996),” 1997, 3.

[28] Bennington College Judson Project interview.

[29] Elaine Summers, “Infinite Choices: Improvisation in Choreography & Filmmaking,” Contact Quarterly, Fall 1987, 34.

[30] Sally Banes, Democracy’s Body: Judson Dance Theater, 1962–1964 (Durham: Duke University Press, 1993), 40.

[31] Quoted in Banes, Democracy’s Body, 41.

[32] Banes, Democracy’s Body, 47

[33] Banes, Democracy’s Body, 53.

[34] Yvonne Rainer, Feelings Are Facts (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, paperback edition, 2013), 223.

[35] Quoted in Banes, Democracy’s Body, 72–76.

[36] Elaine Summers Interview, OHP Library, transcript, p. 222.

[37] Bennington College Judson Project Interview.

[38] Bennington College Judson Project Interview.

[39] Quoted in Oral History Project Interview, 157.

[40] Um, I forget where I read this.

[41] Quoted in Banes, Democracy’s Body, 156.

[42] Don McDonagh, The Rise and Fall and Rise of Modern Dance (New York: New American Library, 1970), 276.

[43] Program notes for Fantastic Gardens.

[44] Billy Linich designed lights for many Judson dances. Known as Billy Name in the Warhol milieu, he was the person responsible for furnishing The Factory with stuff found in the street and for covering the inside in silver—either tin foil, mylar, or silver paint, causing Warhol to comment, “It was the perfect time to think silver.” Source: Andy Warhol and Pat Hackett, POPism: The Warhol ’60s (New York: Harcourt Brace, 1980), 63-65.

[45] Bennington College Judson Project interview.

[46] Jonas Mekas, “Movie Journal,” Village Voice, February 27, 1964.

[47] Jill Johnston, “Summers Gardens, Village Voice, March 12, 1964, Clippings file, *MGZR.

[48] Jennifer Krasinski, “Royal Flux: A book captures the creative impermanence of the Judson Dance Theater,” Bookforum, accessed December 6, 2024.

[49] Susan Rosenberg, Trisha Brown: Choreography as Visual Art (Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press, 2017), 38.

[50] Bennington College Judson project interview.

[51] Dick Higgins, “Intermedia,” The Something Else Newsletter, Vol. 1, No. 1, February 1966.

[52] Niblock started a concert series under EIF in 1973. Since 1985, when he took the helm, EIF has presented numerous American and international artists and created many recordings. Niblock died in 2024.

[53] Don McDonagh, “Summers Dance Joined by Audience in Museum Garden,” New York Times, September 23, 1973, 62.

[54] Daniel Weintraub, dir. documentary film, Deep Listening: The Story of Pauline Oliveros (2023).

[55] All statements about the Intermedia Festival, made in LIVE Performance Art #3, 1980, 12–17.

[56] Quoted in William Grimes, “Hans Breder, Who Broke Artistic Boundaries, Dies at 81,” New York Times, June 23, 2017.

[57] The complete film (twelve minutes) by Elaine Summers, camera and special editing by Bill Rowley, dancers: students of the department of Intermedia, Iowa University, ©1973, 2015 (renewed) Artistic Estate of Elaine Summers, the Jerome Robbins Dance Division, NYPL, accessed January 13, 2025.

[58] Interview with the author, December 17, 2024.

[59] Jack Anderson, “Dance: Solitary Geography, Mixed Media Ode to Nature,” New York Times, July 16, 1983.

[60] Deborah Jowitt, “Heat Record,” Village Voice, July 10, 1984, 71.

[61] Jennifer Dunning, “Dance: Mixed-Media Performance,” New York Times, June 10, 1984.

[62] “How Does This Body Want to Move?: Dancing the Legacy of Elaine Summers,” by Merián Soto, Contact Quarterly, Vol. 44 No.2, summer/Fall 2019

[63] Frances Becker, “Remembering Elaine,” CQ Unbound, accessed December 22, 2024.

[64] Becker, “Remembering Elaine.”

[65] Becker, “Remembering Elaine.”

[66] Maria Harriton, “Elaine Summers: New Forms, New Ideas!” Dance Magazine, September 1970, 66.

[67] Bennington College Judson Project Interview.

[68] Susan K. Berman, “Four Breakaway Choreographers,” Ms. Magazine, April 1975, 39.

[69] Email to author, November 13, 2024.

[70] Juliette Mapp, “Stardust to Stardust: Learning from Elaine,” Movement Research Performance Journal #46, April 2015, 18.

[71] Interview with the author, December 17, 2024

[72] Elaine Summers, “Infinite Choices,” 35. To identify these dancers: Suzushi Hanayagi was a classical Japanese dancer who came to NYC with a scholarship to the Graham school, then got involved in Judson, and went on to choreograph for fourteen productions by experimental theater director Robert Wilson. Reitz is a solo improvisor and faculty member at Bennington College. Eva Karzcag, an extraordinarily fluid dancer in Trisha Brown’s company in the 1980s, is an educator who incorporates Kinetic Awareness in her teachings. Min Tanaka was a Butoh improvisor with an international reputation.

[73] Email from Thomas Körtvélyessy, artistic executor of the Elaine Summers estate, December 19, 2024.

[74] Phone interview with the author, December 10, 2024.

[75] Oral History Project Interview transcript, 307.

[76] Quoted in Anna Kisselgoff, “Cooking with Intermedia,” New York Times, February 18, 1977.

[77] Douglas Dunn, “In Celebration of Elaine Summers,” February 20, 2021, accessed December 12, 2014.

Unsung Heroes of Dance History 1

This is an absolute joy to come across such an extensive sharing of Elaine’s life. I studied and then danced with Elaine in the mid 1970’s.