With the farewell of Ashley Bouder last month, I realize that she is the last of a cluster of brilliant ballerinas I admired at NYCB some years ago. I happened to come upon this review that I wrote of the Winter Season in the May, 2007 issue of Dance Magazine. As I look back, I see that all the principals I describe here have gone on to leadership positions, and the soloists I named at that time have stepped up to be NYCB royalty.

Winter Season, NYCB, Jan. 3–Feb. 25, 2007

Dance Magazine, May 2007

In a season of 38 ballets, the dancing of NYCB’s women came to the fore. In both familiar and new roles, the female principals blossomed into their full ballerina glory. Janie Taylor gave Robbins’ Afternoon of a Faun an outsize sensuality that was mesmerizing…

Ashley Bouder, every inch a creature of impulse, put the fire back in Firebird. She exuded power, she shimmered and shattered the demons. And yet at the end she revealed a certain sadness…

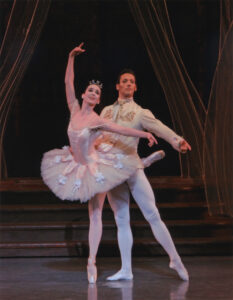

Jenifer Ringer was a burst of innocent joy as Aurora in Sleeping Beauty, and oozed glamour as the woman in black in Balanchine’s Vienna Waltzes …

Wendy Whelan, slow as a floating cloud, light as air, imbued Balanchine’s Mozartiana with a celestial presence…Jennie Somogyi, jazzy and juicy, had a thrilling physicality in the master’s Symphony in Three Movements. Her Lilac Fairy ruled Sleeping Beauty with such expansive benevolence that I wished she could come and bless my household too…And there was something inexorable about the swooping and soaring of Sofiane Sylve, as dazzling as her crown in Balanchine’s Tschaikovsky Piano Concerto No. 2.

Among the men, Damian Woetzel was superb, more than superb, in A Suite of Dances, the solo Robbins made for Baryshnikov in 1994. He graciously communed with Ann Kim, the onstage cellist playing Bach. Mischievous and nonchalant, he slipped slyly from earthy folk steps into whizzing multiple turns. He was a welcoming host, virtuoso technician, and wise-guy adolescent all at once.

The soloists, who danced lead roles as often as the principals, were less dependable. We saw a lot of Teresa Reichlen, Sterling Hyltin, Abi Stafford, and Tiler Peck. Hyltin tends to overdo and is weak in her center but was fun and flirty in Martins’ Jeu de Cartes and elegant in Feld’s Intermezzo No 1. Stafford tends to have more determination than flow; however she loosened up in Walpurgisnacht Ballet. In Mauro Bigonzetti’s In Vento, Peck was gutsy in a brazen broken-limb solo and duet, but in Martins’ Friandises, she was a bit brassy. Reichlen’s lovely gentleness and fluidity graced many roles, but she could have used more crispness in the Agon clicking solo and more authority as the Lilac Fairy.

The sprightly Daniel Ulbricht and the full-bodied Sara Mearns were the most consistent soloists. One of the best technicians in the company, Ulbricht bounded with unforced eagerness in all his roles. Mearns had warmth and allure in all of hers.

And some corps members stood out. Wide-eyed Tyler Angle breathed fresh air into classical roles with his ease, smoothness, and line. Stephanie Zungre teased and snapped her paws with expert comic timing as the White Cat in Beauty. Sean Suozzi boldly extended into space with strength and assurance, exemplifying the drama of black and white in Agon. And Kathryn Morgan was achingly lovely as the ingenue in Wheeldon’s Carousel (A Dance).

Choreographically, the highpoint of the season was Jorma Elo’s Slice to Sharp. One of four ballets repeated from last spring’s Diamond Project, it takes NYCB’s non-narrative tradition and rockets it into the future. With its sheer momentum, veneer of anarchism, and a semaphoric code language that lent a touch of mystery, it blows away the orderly lines of both Petipa and Balanchine. Using centrifugal force, it sends the dancers spinning and hurtling through space off-kilter. There are daredevil slides along the floor, windmilling arms, jutting pelvises, big wheeling lifts, a lot of “open sesame” hand moves—the whole piece is a magic carpet ride. The motif of touch-reaction—or rather near-touch-guess-the-reaction—makes it seem like invisible strings tie one action to another. A man touches a woman’s waist and her knees knock inward. A woman whips her leg and just misses the chest of a man in a backbend. Facing upstage with her hand behind her neck, Maria Kowroski slithers her head sideways and back into place behind her hand. It’s a bit of fun voguing, one of many small surprises that spill out and make you keep your eyes peeled. The men dance to the hilt, especially Edwaard Liang and Joaquin De Luz, who dive into their partnering and crazy pirouettes.

The one premiere, Christopher d’Amboise’s Tribute, in honor of Lincoln Kirstein, has clear structures, a gentle humor, and old-time chivalry (lots of bowing and curtsying). Embedded in it are quotes from famed Balanchine ballets, like the sudden opening into first position of Serenade, and the bent-knee jump the men do on the first notes of Agon. It ends with a beautifully spooling pas de deux for Bouder and Tyler Angle. She dances with delicacy and authority, and he really seems to care about her. Twice, she leaps and he assists her mid-leap before taking her for a big lift. You can hear a collective sigh from the audience when they go whirling off.

The major revival was Robbins’ Dybbuk (1974), which seems to be about a wronged couple facing society—or at least a posse of rabbis. (A dybbuk, in Jewish folklore, is a lost soul, a spirit of the dead whose voice enters the body of a living person.) Seven men in black with caps could be cousins of the bottle dancers in Fiddler on the Roof. However, the hieroglyph-like backdrop by Rouben Ter-Arutunian gives it a mystical tinge. The Bernstein score, with its vocal sections à la Stravinsky’s Les Noces, emphasizes community and ritual. The high-point is an entwining duet for Ringer and Benjamin Millepied, as though to get under each other’s skin. But never does the ballet have the power of the original play, The Dybbuk, by S. Ansky, in which the voice of Leah’s dead lover possesses her—two tormented souls in one body.

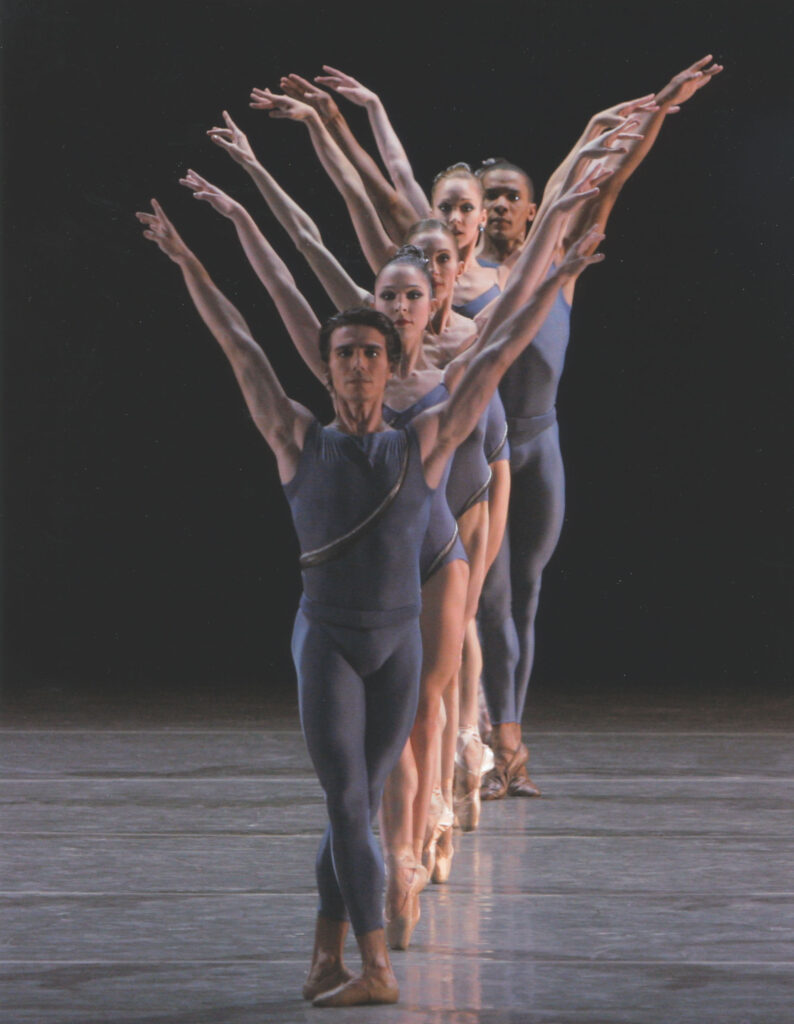

Russian Seasons with Albert Evans, Rebecca Krohn, John Stafford, and Rachel Rutherford, ph John Ross

Another popular holdover from the Diamond Project was Alexei Ratmansky’s Russian Seasons. With long, bright-colored dresses, it has a folksy charm. There is a wonderful twisty solo for Albert Evans (it’s good to see him move), and for Sean Suozzi a fine solo with sudden jumps. There are funny touches, as when two crouching men, their shirts riding up in back, pull their shirts down in unison. Jenifer Ringer has a nice playful solo and a poignant scene where she walks on a path in the air made by the men’s hands. But some moments are hokey, like dancing in a line-up that looks like a bunny hop. It has the quaint feel of a work from long ago, like, say, Sophie Maslow’s The Village I Knew (1949). More intriguing was Ratmansky’s Middle Duet, performed only once, on opening night. In that brief sketch, with haunting music by Yury Khanon, Maria Kowroski’s elegant attention to simple tendues was somehow transporting.

Mostly, the Balanchine ballets provided the perfect setting for the dancers to shine. But a few of them, for example, Monumentum pro Gesualdo, Duo Concertant, and Stravinsky Violin Concerto, may be losing some of their appeal. There are those who argue that these ballets are no longer performed well by City Ballet. However, I feel that choreographically they represent a time gone by, a time of orderliness and politeness. Ballets that slice through that remoteness (other than Slice to Sharp) are the atmospheric ones: Robbins’ Afternoon of a Faun, Martins’ staging of Sleeping Beauty, Wheeldon’s darkly glamorous Klavier, the Balanchine/Robbins Firebird, Bigonzetti’s In Vento, and Balanchine’s Vienna Waltzes. These ballets pull you into a different world and make you care about the characters. When they are over, you feel nourished by the art, sated with the fullness of people dancing.

Some updates, as of March 1, 2025: Wendy Whelan is Associate Artistic Director of NYCB; Janie Taylor is Artistic Director of Colburn Dance Academy in L.A; Jenifer Ringer (the previous director of Colburn), now teaches at SAB; Maria Kowroski is at the helm of New Jersey Ballet; Edwaard Liang is Artistic Director of The Washington Ballet; Joaquín De Luz stepped down after five years as Artistic Director of Compañía Nacional de Danza. Benjamin Millepied is founder/director of L.A. Dance Project. Jennie Somogyi runs the Jennie Somogyi Ballet Academy in Pennsylvania. Sofiane Sylve leads Ballet San Antonio. Damian Woetzel is President of Juilliard. All this makes me wonder where Ashley Bouder will land in the near future.

Featured Leave a comment

Leave a Reply