The book cover features Suzanne Miller in “Needle and Thread,” reflecting dance as memorial, Ph Daniel Paquet.

The far-reaching Oxford Handbook of Jewishness and Dance is both a culmination of decades of scholarship and a new look into the intersection of dance and Jewishness. No longer an obscure, occasional practice, Jewish dance scholarship has arrived. It has been accumulating for years, with Judith Brin Ingber, to whom the book is dedicated, leading the way. Researchers like Dina Roginsky, Henia Rottenberg, and Nina Spiegel have carried the torch. Young scholars like Hannah Kosstrin and Rebecca Rossen have recently given us provocative books and essays, laying the foundation for this new phase of investigation.

This anthology of thirty essays, published by Oxford University Press, was sparked by a stimulating conference held at Arizona State University in 2018. Titled “Jews and Jewishness in the Dance World” and organized by Naomi Jackson, it attracted hundreds of dance artists and educators from all over the world. It was a warm gathering—emotional at times—crammed with talks, demonstrations, and workshops. At the end of three days, we were treated to an evening of performance of inspiring works by Sara Pearson, Ephrat Asherie, Adam McKinney, Jesse Zaritt, Nicole Bindler, Maggie Waller, and Hadar Ahuvia. David Dorfman and Dan Froot topped it off with a rollicking ride, complete with sly Yiddishisms and dancing for all. (Full disclosure: I co-curated the concert with Liz Lerman, who was a co-organizer of the whole conference with Jackson.) Happily, the companion website connects to resources like video clips, so I’ll be giving specific links along the way.

The scope and depth of this 737-page tome are invigorating, evoking pride, joy, sorrow, outrage and all kinds of mixed emotions. Kudos to the editors—Naomi Jackson, Rebecca Pappas, and Toni Shapiro-Phim—for stretching us in many directions. The contributions of young dance-makers like Hadar Ahuvia, Jesse Zarrit, Adam McKinney, and Yahuda Hyman are each brilliant in articulating a broken-ness that needed to be repaired… internal tikkun olam that engages with the world through art. What you won’t find is a lot of coverage of Israel’s flagship company, Batsheva Dance Company, or the development of Israeli folk dance. The reason, as explained in the Introduction, is that these areas are amply covered elsewhere. So when these topics appear in this volume, it is usually through the lens of a critique.

Although it’s clear from the choice of the word “Jewishness” rather than “Judaism” that the thrust is toward a cultural rather than religious definition, a few chapters do swing toward religion. Examples are Jill Gellerman’s essay on inclusiveness in Hasidic dance, Efrat Nehama’s “My Body Is My Torah,” and Talia Perlshtein, Reuven Tabull, and Rachel Sagee’s chapter on dance in the religious sector of Israel.

First-Person stories

I tend to gravitate to personal stories, so I will touch on six inspiring tales, told with complexity and intensity. Four of them are by young firebrands, and two are by respected elders Judith Chazin-Bennahum and Ze’eva Cohen. They have all found ways of integrating their passion for dance with their Jewish heritage. They’ve reimagined their identities to arrive at who they have become and are becoming.

Hadar Ahuvia, who grew up in Israel and the U. S., questions the Zionist legacy in her essay “Joy Vey: Choreographing a Radical Diasporic Israeliness.” When she learned about the Nakba (the Palestinian word for the disaster of the birth of Israel and expulsion of Palestinians), it shattered the anchor of Zionism as a “grounding force.” She wrestled with her old beliefs, utilizing Israeli folk dance—her attachment to, and yet interrogation of—to embrace multiple identities. She articulates her inner, political struggle in the bracing solo Joy Vey, with a bit of guidance from Jeanine Durning’s method of Unstopping. In it she skims the earth with folk dances learned as a child, while hearing an incantatory voice (her own on recording) in a litany imagining another reality. (“And maybe they never fled because they were never there, Maybe we didn’t shoot at them as they left to make sure they never returned.”) I add here that her performance of an excerpt of Joy Vey was a powerful, mesmerizing contribution to the final concert of the conference.

For Adam McKinney, being Jewish is only part of a difficult yet sometimes joyful multiple identity. His writing in “HaMapah/The Map: Navigating Intersections” reveals a sweetness and vulnerability, and yet a determination to uncover his tangled roots. As he plays with words, he answers to “boychick” in the Yiddish sense, but also claims his feminine side in the “chick” portion. When tracing his family history, some of it violent, he calls himself “GayBlackNativeJewish.” He doesn’t want his multiple identities to be wedged into “otherness.” You can see his powerful, soulful dancing and storytelling in these clips.

Jesse Zaritt, who teaches at Philadelphia’s University of the Arts, wrote about how being gay was definitely outside his Jewish upbringing. A sharp, painful clarity on his outsider-ness informs his essay send off, which is about his piece of the same title. Send off harks back to ancient biblical stories with a stinging sarcasm. After an immersive journey in dance, Zaritt has arrived at a place that is somewhat of a tortured elegy but also fluidly himself:

In send off my whole body at once reaches forward toward a fantasy of queer potentiality and backward toward an imaginary erotics of ancient Jewish embodiment …I am a man who is still a boy… I am the caretaker betraying and betrayed by those he loves. I am the divine feminine…And I am an animal about to die. In collapsing four unruly beings into one, I find myself uncomfortably, impossibly, in a willful, passive, wise, and wild body. I am trying to create a new being made of the parts these four characters have played.

If you want to catch an excerpt of Jesse Zaritt’s send off, accompanied by Israeli playwright Hanoch Levin’s hilariously sarcastic yet powerful dialog riffing off of Abraham’s willingness to murder his own son, click here.

Dege Feder, an Ethiopian Jew, came to Jerusalem from her small village in northern Ethiopia, where she herded goats at age 6. She would sing while minding the goats, but music and dance as performance were nonexistent. At 8, she walked barefoot to Jerusalem, with a group of people who sometimes left her behind. (The Ethiopian government would punish anyone caught trying to emigrate with prison or death, so refugees could only walk at night. The courage of this child is staggering.). When she arrived in Jerusalem, she eventually taught dance to the Ethiopian community. At the University of Haifa, she encountered Ruth Eshel, the Israeli dance maven who engaged with Ethiopian communities with the notion of dance as a cultural bridge. Feder joined Eshel’s Eskesta Dance Theater, which centered on the percussive Ethiopian shoulder dance called eskesta—first as a drummer and then as a dancer. The company broke up and then resumed under the name Beta Dance Troupe. Feder became its soloist, and then, in 2013, its director. This enchanting music video, titled Amaweren’ya (2017). shows her singing (sheer charisma), dancing that crazy shoulder dance (parts of the upper body jutting in different directions), and activating a multi-generational community.

Stories of Two of Our Elders

For Judith Chazin-Bennahum, dance was so central to her early life that it crowded out Judaism. But in her mini-memoir, “The Nearness of Judaism,” she takes us through her transformation from a ballet girl to a dance historian, increasing her commitment to Jewishness along the way. While performing with the early Joffrey company and the Metropolitan Opera Ballet, she took note of Jewish dance artists like Melissa Hayden, Bruce Marks, Doris Rudko, Pearl Lang, and Judith Dunn. Eventually, as expressed in her final sub-section, “My Body and Soul Merge,” she finds a way to balance dance with family and Judaism. She writes of the common ground she found in ballet and the Torah:

I loved the sense of inevitability, that one thing followed another and that movements needed to be accomplished the same way pretty much all the time, only better. Dancing in tune with others was thrilling, and keeping together reassuring. I found out later that the rigor of studying the Torah required a similar obsession with learning, with knowing what came next, with a joy in the ritual of habit.

Today Bennahum is a foremost dance scholar who has written books on pivotal Jewish figures, namely René Blum and Ida Rubinstein.

###

Ze’eva Cohen, a harbinger of the current trend in cultural identity dances, grew up as a Yemenite Jew in British Mandate Palestine, later to become Israel. Her story is a must-read for anyone interested in the connection between Israeli and American dance. Her insights about Gertrud Kraus (lots of improvisation), Sara Levi-Tanai (channeling her Yemenite heritage into Inbal Dance Theater), and Margalit Oved (muse of Levi-Tanai and star of Inbal) are compelling. Not to mention her work with Anna Sokolow, who brought Cohen to Juilliard. Cohen’s breakthrough at Juilliard was dancing in Doris Humphrey’s rippling Ritmo Jondo. (I saw her perform in this work in the 1960s and have never forgotten her light-giving, sensual magnetism.) As a solo performer touring with her own rep, she crossed many cultural barriers. While being true to her Middle Eastern heritage, she also found “otherness” within herself as a performer working with contemporary choreographers like Rudy Perez, Viola Farber, and James Waring. When Cohen started to choreograph, she unconsciously circled back to her Yemenite background. (At the conference, Ze’eva gave a workshop in which she taught the deceptively simple Yemenite step that appears in Israeli folk dance.)

Ze’eva Cohen as Rebecca in “Mothers of Israel” by Margalit Oved, 1979, Pd John Lindquist © Harvard Theatre Collection.

Cohen points out that Inbal, the first internationally touring dance company of Israel, was populated with Yemenite immigrants who were perceived to be “authentic,” meaning close to biblical times, but not “professional” modern dancers. When, years later, she commissioned Oved to choreograph Mothers of Israel for her, she felt that “I became my grandmothers.” You can see a number of clips of Mothers of Israel and Ze’eva’s own choreography here. (There is more about the remarkable, captivating singer/dancer/storyteller Margalit Oved in Nina S. Spiegel’s chapter, “Mapping a Mizrahi Presence in Israeli Concert Dance.”)

The Ever-Present Holocaust

The Holocaust is addressed with all the weightiness needed. One of the most intense personal connections with Holocaust history is related in Yehuda Hyman’s “Dancing on Smoke: A Dance Action in Germany.” Hyman visited a reflecting pool in Freiburg designed as a commemoration of a synagogue that had been burned to the ground during Kristallnacht in 1938. When he saw the casual, party atmosphere of people around the pool—and no visible plaque to mark the atrocity—he became upset. Not speaking German, he felt an absolute necessity to take physical action. He stepped into the pool with his challis and yarmulka, took out his tallis and recited a prayer. He walked, he moved, he screamed. As he recalls,

My body is summoning up a story about the destruction that lies below me…I start to…embody what I am discovering in the pool and executing every Jewish gesture I know. So I’m doing ‘The Wise Jew,’ I’m doing ‘The Happy Jew,’ I’m doing ‘The Sad Jew’ and then…the traumatized displaced Jew whose body is in shock and can’t move at all.

Hyman’s action became known as “Jew in the Pool.” He reprised it a year later, this time dancing for three days in the pool. It inspired a vigil, some protests, and finally, the installment of signs showing the burnt synagogue and pictograms forbidding certain actions. This did not entirely stop the disrespectful behavior. But for Hyman, he’d been through something: “For me the pool represents the body of the Jewish people and the act of defaming that body feels like a violation of my body…I danced on tragedy, beauty, and community.”

###

Marion Kant brings up Primo Levi’s statement, “There is Auschwitz and so there cannot be God.” His follow-up question is the title of her essay, “Then in What Sense Are You a Jewish Artist?” Levi’s answer is, “The racial laws and concentration camp stamped me the way you stamp a steel plate… They made me Jewish.” Kant goes into the history of German culture in which she mentions that the plot of Giselle (1841) draws on a narrative by the Jewish Heinrich Heine as “a tale of the Jewish struggle for emancipation.” There’s lots more complex history, which I don’t entirely grasp. But I did pick up one surprising point: Based on Heine and the integration of Jews at the loftiest levels of German culture, Kant contends that ballet in the 19th century was more open to Jewishness than German Modern Dance in the 20th century (e.g. Laban, Wigman), which tended to be nationalistic. She concludes that a sense of responsibility is necessary to reach “the emancipation of all humanity.”

###

Laure Guilbert studied the rare incidents of dancing amidst the hell of the death camps. In “The Micro-Gestures of Survival: Searching for the Lost Traces,” she retains an elegant balance between theory (e.g. Kafka, Bettelheim, Adorno, Deleuze) and encompassing the enormity of evil and suffering. The prisoners were considered “mere shadows without names or faces,” and yet a few of them managed to reclaim their souls through some kind of dance. She tells of the harrowing bravery of Tajana Barbakoff, Yehudit Arnon, Helen Lewis, and Catherina Frank. Dance played a role in the imagination that kept their minds alive, and sometimes dancing for SS officers kept them physically alive. Guilbert calls these moments of dance “the final act of life amidst their own death sentence. In a larger sense, they also embody and condense the final gasp of German-Jewish and Eastern European Yiddish cultures.”

She also calls them “a testament to the human impulse to save humanity even in the very moment of its radical destruction.” The inner life, amidst the hunger and humiliation, can be preserved in memory or movement. Hella Tarnow, trained in Indonesian dance, used the sense of touch to bring back physical sensation to prisoners. Miraculously, Helen Lewis was able to forget the freezing cold, the pain, and the hunger when her fellow campmates asked her to dance to Delibes music. Although these brief moments could not put a dent in the infernal Nazi machine, they are “the very ethical and poetic support structure, that makes survival possible in those places.”

Yehudit Arnon, an Auschwitz survivor included in Guilbert’s account of prisoners’ bravery, became one of the giants of Israeli dance. Gdalit Neuman, in “From Victimized to Victorious,” studies Arnon’s project in Budapest right after the War, when Arnon worked with young women to strengthen their bodies and spirits, thus changing the gender balance. Arnon went on to establish the International Dance Village at Kibbutz Ga’aton and the award-winning Kibbutz Contemporary Dance Company. (If you want to know more about the seminal Arnon, see Judith Brin Ingber’s entry on her in Jewish Women’s Archive.)

###

Rebecca Rossen focuses on The Ivye Project (1994), the magical, site-specific work that Tamar Rogoff created in a forest in Belarus. When Rogoff first visited Ivye, she learned that twenty-nine members of her father’s family perished in the massacre of May 12, 1942. To mourn them, she has to know them, and to know them, she has to spend time there. She gathered more than a hundred people—very few of them Jewish for the simple reason that most Jews had been murdered—to take part in a time-travel work that depicted Jewish shtetl life in Belarus while also marking the Nazi massacre. Scenes included a seder, a man putting his daughter to bed, a couple feeding each other, a game of cards, and a Sabbath celebration with live music by Frank London and the Klezmatics. Luckily, the companion website gives glimpses of The Ivye Project that allow you to feel you’re in the forest experiencing Rogoff’s wondrous version of Jewish life at the time.

Rossen discusses the after-effects on the town and the performers, some of whom were children of survivors. She quotes the cast historian saying,

People needed to see that Jews used to live in Ivye. That there were artisans, tailors, shoemakers, that there were also lazy bones and there were saints. All of us were involved, we didn’t act in the performance, we lived it.

There was a realization that what was lost was not only 2,524 lives, but a whole way of life. As Rossen’s writes, “The Ivye Project resurrected a suppressed Jewish history and invited a diverse group of people to witness and actively participate in reviving and narrating it.”

###

Anna Halprin in “My Grandfather Dances,” NYC, 1999, Ph Julie Lemberger.

Naturally, the Holocaust crops up in many other places, for example, in the interview with Anna Halprin by Ninotchka Bennahum. (Ninotchka is the daughter of Judith Chazin-Bennahum.) A dance pioneer who claimed her Jewishness both as religion and as moral philosophy, Halprin says that her early solo The Prophetess (1947), about a powerful woman judge in the bible who protects her people, was also meant as “a way of fighting back against the Nazis.” Halprin is represented on the companion website by her poignant/funny solo My Grandfather Dances (2003) and her landmark performance piece, Parades and Changes (1965). (These works are discussed in the interview’s prelude, which is based on Bennahum’s research for Radical Bodies, an exhibit and book that Ninotchka and I were, along with Bruce Robertson, co-curators on.)

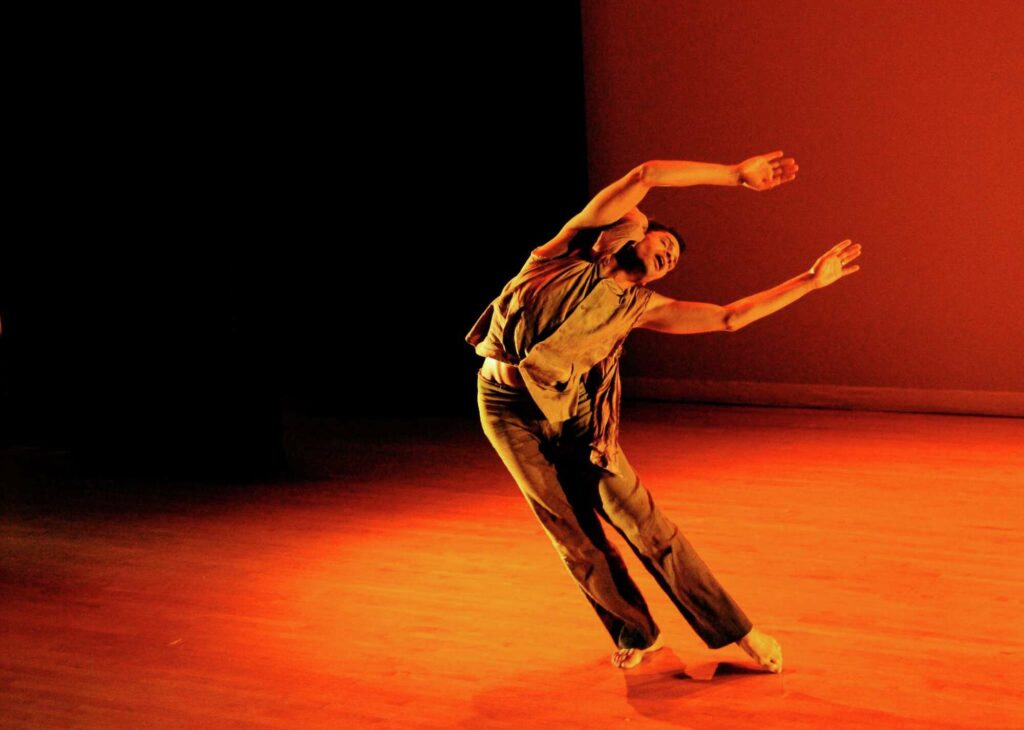

Others who wrote about Holocaust-related projects include Rebecca Pappas, Alexx Shilling, and Suzanne Miller.

Tying Modernism to Jewishness

Douglas Rosenberg offers an art-historical underpinning to Jewishness in modernism in his essay “It Was There All Along: Theorizing a Jewish Narrative of Dance and (Post-)Modernism.” He frames it as a ghost history, saying that the recognition of Jewishness in dance means it’s no longer veiled. He sees Jewish identity as familiar, historical, and tribal. One of the principles is tikkun olam (repairing the world), a value that runs throughout this book. Rosenberg makes a connection between Dada, Susan Sontag, Clement Greenberg, and “hidden Jews” of the Avant-garde.” Referring to Tristen Tzara, born Samuel Rosenstock, and Man Ray, born Emmanuel Radnitzky, he invokes other Jewish artists, like Mark Rothko and Allen Kaprow, to draw parallels. In terms of dance, he talks about the contribution of Jewish women to modernism, invoking Meredith Monk, Sally Banes, Liz Lerman, and Sally Gross, to whom this landmark essay is dedicated. He refers to all these artists as examples of “the ecosystem of Jewishness that traverses modernism.” He compares Sally Gross, one of the Judson Dance Theater experimenters who is not often mentioned, to painter Mark Rothko in creating a “sacred Jewish space.”

And More

There isn’t space here for everything. But I want to mention the chapter on Felix Fibich (by Naomi Jackson, Joel Gereboff, and Steve Lee Weintraub), the early modernist who defined the Jewish soul as marked by both joy and sadness, thus creating a torque in the body. And Dana Shalen’s chapter on Arkadi Zaides, the radical Belarus-born choreographer who brought Israelis and Arabs together. In his tremulous quartet, Quiet, two Israeli and two Arab men broke cultural barriers by tenderly or violently touching each other. (When I saw this in Tel Aviv, a lightbulb shattered above their heads; although it wasn’t intended, it was a perfect metaphor for shattering cultural taboos.) An innovative workshop dreamt up by Victoria Marks and Hannah Schwadron led to their essay “I, You, We: Dancing Interconnectedness and Jewish Betweens.” Miriam Roskin Berger, Marsha Perlmutter Kalina, Johanna Climenko, and Joanna Gewertz Harris write about the Jewish roots of dance therapy. There are more stories about various aspects of Israeli dance by Melissa Melpignano, Dina Roginsky, and Joshua Schmidt, and a politicized view of Ohad Naharin’s Gaga practice by Meghan Quinlan. And interesting entries by Philip Szporer, K. Meira Goldberg, Liora Bing-Heidecker, Christi Jay Wells, Avia Moore, and Eileen Levinson. So sorry to lump all these chapters in one paragraph.

In the book’s conclusion, Kosstrin cherishes every contribution (as do I) but also nudges us toward confronting gnarly dilemmas. She suggests a more feminist language and a less European (Ashkenazy) lens through which to investigate the interconnectedness of Jewishness and dance. For non-Ashkenazy lineage, she gives the example of the hand mudras used by both Margalit Oved and her son Barak Marshall. These gestures migrated from Yemen to Israel to the States. She advocates scholars “grappling with the entangled aesthetics and politics embedded” in choreography. She wants us to notice “the tension between Jewishness and Israeliness” (which, I would say, is more keenly felt by the younger generation). And she situates Jewish dance scholarship in the context of other cultural dance studies: Black dance studies, Latinx, South Asian, native and queer dance studies. Kosstrin ends with a series of questions. For example, when talking about the aggression of Israel’s government toward Arab communities, “How do we engage in dance in ways that show empathy and vigilance?” Nu…what could be more Jewish than asking questions?

It takes time to absorb the diverse and deep views in the Handbook. Time to sort through the chapters, return to some of them, make connections. Time to allow oneself to evolve, to gain or lose or reclaim different aspects of the intersection of Jewishness and dance. Spirituality and art. Culture and choreography. History and the contemporary world. What it means to be a Jew, to be a Jewish dancer, and how that changes at different times of one’s life (as anti-Semitism continues to rise and fall). A final note: “Handbook” is a misnomer. This book is a treasury of gems of courage, creativity, storytelling, and research. L’chaim.

¶¶¶

Featured 4

I thoroughly enjoyed reading your review of the book. I found that your introductory and conclusive remarks, and your comments on the six personal stories written by culturally diverse artists (me included), captured so well the purpose of this expansive book. The book places Jewish dance in global cultural context, which is refreshing, welcome, and much needed.

Wow! What an incredible documentation of the many dimensions of this cultural, political, creative, dance legacy. Congrats and bravo to Wendy Perron, Naomi Jackson and all!

I want this book.

It is definitely a book to cherish. The link is where I wrote Oxford University Press.