One of the most exciting periods of the Merce Cunningham Dance Company was the late sixties and early seventies. Cunningham himself was still dancing magnificently. Composer/philosopher John Cage was still driving the Volkswagen mini-bus on tour. And the company was making and performing some of the most iconic works of contemporary dance.

One of the most exciting periods of the Merce Cunningham Dance Company was the late sixties and early seventies. Cunningham himself was still dancing magnificently. Composer/philosopher John Cage was still driving the Volkswagen mini-bus on tour. And the company was making and performing some of the most iconic works of contemporary dance.

Luckily, during part of that period (1967 to 1972), the young photographer James Klosty chronicled the company, which was an ensemble of highly individual dancers. In the introduction to his original 1975 book, Merce Cunningham, Klosty wrote that although Cunningham worked with musicians and visual artists, the dancers were his “only true collaborators.” This became less and less true, as the age gap between Cunningham and his dancers widened—which is why the visual evidence of this period is to be cherished.

For the Cunningham centennial last year, Klosty re-issued and augmented his book, now titled Merce Cunningham: Redux, published by powerHouse Books.

With 140 pages of additional photographs, in alluring, rich duotones, the new version is even more of a treasure chest of images and essays, shedding light on a bold development in contemporary dance—the tectonic shift from modern dance to postmodern dance.

Rainforest w Mel Wong & Meg Harper, decor by Andy Warhol

During those five years, Klosty had an intimate relationship with Carolyn Brown, Cunningham’s most frequent partner. With his spouse-of-dancer status, he traveled with the company everywhere. That intimacy spills over into the studio and backstage. We see Cunningham and Brown work together, laugh together, quibble together. We see dancers reflecting on their next or last move. We are privy to relaxed moments of camaraderie as well as intense moments of striving to embody Cunningham’s vision—which included the dancers being totally themselves.

Cunningham famously broke with the narrative tradition of modern dance—specifically the psychological drama of Martha Graham. But he created his own brand of drama. The photos capture a sense of spontaneity within a rigorous structure. These images are so magnetic that we feel like we are right there with the dancers. The taut leg muscles, wide open eyes, and flesh-to-flesh comfort of the dancers have a sensual quality. Each dance has a different look, depending on whether the visual artist is Robert Rauschenberg, Robert Morris, Jasper Johns, Beverly Emmons, Bruce Nauman, Marcel Duchamp, or Andy Warhol.

Merce and Valda Setterfield in Second Hand

A particular elegiac moment captures Merce leaning back with Valda Setterfield’s head resting on his chest in a rehearsal of Second Hand in Paris. Another moment finds Viola Farber, while partnered by Merce in Crises (1960), in partial contraction with leg extended, looking tortured. A shot of Merce thrashing around in a big plastic bag in Place (1966), looking like he’s drowning, is atypically grainy.

In keeping with the Cunningham/Cage entwinement of art and life, the book commingles performance with the everyday. We see the dancers onstage in works like the absurdist Antic Meet, the darkly alarming Winterbranch, and the playful Tread; we also see them hard at work in rehearsal. Klosty follows the group from the peeling walls of the Third Avenue studio to the light-flooded, open space of the Westbeth studio, where the company moved in 1972.

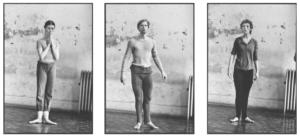

Sandra Neels, Douglas Dunn, Valda in Third Avenue studio

While archivist David Vaughan’s essential book Merce Cunningham: Fifty Years, encapsulates almost every finished work by the choreographer, Klosty has caught a myriad of candid moments of the dancers at work and at play in a particularly fertile five-year period. For the everyday, we see the dancers napping in the sun, Viola Farber gleefully giving a haircut to artist Jasper Johns, and Merce reaching through a cluster of passengers to grab a suitcase from a luggage carousel. And for the site-specific, we see a number Events (Cunningham’s way to recombine pieces of pieces for a particular setting) in Paris, Grenoble, and Belgrade.

It’s hard to imagine how Klosty gained such continual access. I asked choreographer Douglas Dunn, who was in the company at the time, about his memory of Klosty’s presence. In an email, he wrote, “Jim on tour and in NYC managed to be a delightful presence and an invisible photographer. I don’t recall ever seeing him take a snap. He was friendly with anyone (like me) who wanted to convene, but, without seeming nervous, kept a distance based, I’m guessing, on what he sensed Merce (and the rest of us, each different in degree of self-consciousness) would accept. Once in a while, during the lull between the day’s preparation and the show, you might find him playing the grand piano in the pit—with considerable virtuosity.”

Carolyn Brown and Merce at Westbeth studio

The essays and reminiscences about Cunningham have been kept intact. We can recognize Carolyn Brown’s essay as the seed for her revelatory book, Chance and Circumstance: Twenty Years with Cage and Cunningham. She describes the choreographer with great vividness: “His own dancing is suffused with mystery, poetry and madness—expressive of root emotions, generous yet often frightening in their nakedness . . .He moves with leopard stealth and speed and awareness and intention.” She also talks about his challenge to the dancers: “Merce requires…that the rhythm come from within: from the nature of the step, the nature of the phrase and from the dancer’s own musculature, not from without, from a music that imposes its own…rhythms.”</span>

Other entries are by Yvonne Rainer (who was influenced by Cunningham but was never in his company), Douglas Dunn, and Viola Farber as well as composers John Cage, Gordon Mumma, Earle Brown, Pauline Oliveros and Christian Wolff.

Also included is a letter that ballet mogul Lincoln Kirstein wrote to Klosty, with his usual belittling of modern dance. He deigns to say that he likes Cage and Cunningham personally but not their work. He contends that without 400 years of the ballet academy behind them, their work cannot possibly last. To my mind this reveals how ultra-conventional Kirstein was, while posing as someone in the know. (Kirstein is revered in ballet circles as the person who brought George Balanchine to the U.S.; he was also instrumental in the founding of the Museum of Modern Art.) Kirstein’s vitriol against modern dance has been aired on many occasions. I suppose it provides a frisson of controversy, but I felt at the time of Klosty’s original book—as I do now—that his screeds against modern dance were irresponsible.

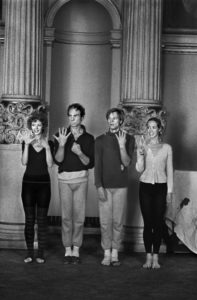

Valda, Merce, Douglas, Susana Haymen-Chaffey in rehearsal of Signals

Some of the written entries reach back in time. The great American dance critic Edwin Denby reviewed an early Cunningham concert in 1945, saying, “Mr. Cunningham reminds you there are pure dance values in pure modern technique. He is a virtuoso, relaxed, lyrical, elastic like a playing animal . . .He has a . . . drive and speed which phrases his dances; and better still, an improvisatory naturalness of emphasis which keeps his gesture from looking stylized or formalized.”

Those who have studied with Merce often think of him as a Zen master. And many of these photos possess a kind of tranquility. But he also brought a bracing edge to his work that rubbed off on his dancers. The whole enterprise during the Klosty years was marked by precision, purpose, and a readiness for abandon.

In the foreword to the Redux version, Klosty writes, “Images of Merce’s dances performed when he was in his prime have acquired a poignancy and power I didn’t anticipate forty-five years ago.” D’accord. Whether or not you saw the original 1975 version of this book, the beauty of these photos have accumulated over time.

Note: This article was commissioned by Tanz magazine and first appeared in German in its April issue.

Featured Leave a comment

Leave a Reply