This list is subjective; it reflects my taste as well as that of the writers represented here. It is not in any particular order. Please feel free to comment below or suggest your favorite dance book of the year. Btw, sometimes a books is released too late in the season for me to catch up, in which case I try to consider it the following year…. Enjoy.

Edges of Ailey (exhibition catalog)

Edited by Adrienne Edwards; contributions by Horace D. Ballard, Harmony Bench, Kate Elswit, Aimee Meredith Cox, Thomas F. DeFrantz, Malik Gaines, Jasmine Johnson, Joshua Lubin-Levy, Uri McMillan, Ariel Osterweis, J. Wortham, CJ Salapare, Kyle Abraham, Claire Bishop, Masazumi Chaya, Brenda Dixon-Gottschild, Jennifer Homans, Judith Jamison, Sylvia Waters, Jamila Wignot, and Jawole Willa Jo Zollar.

Whitney Museum of American Art, distributed by Yale University Press

Reviewed by Robert Johnson

Though it threatens to up-end the coffee table, the catalog of the Edges of Ailey exhibition at the Whitney Museum of American Art is a handsome volume that every fan of the late choreographer and his Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater will be proud to own. Looking gold-plated in its foil dust jacket, this tome also contains a plethora of gorgeous illustrations. It supplements the checklist of the exhibition with exciting dance images not displayed at the Whitney, with commissioned essays, a list of Ailey’s own choreographies, an annotated chronology (up to 2014), and a rollcall of company dancers through 1989.

Editor and curator Adrienne Edwards and a team of researchers have plunged into the company’s archives and have retrieved amazing documents that illuminate the choreographer’s dreams, his personal struggles, and his success. Yet the magnitude of Ailey’s achievement becomes apparent, when we realize that this scholarship still falls short. Neither the exhibition nor the catalog provides a comprehensive account of the AAADT’s repertoire. While complaining that dance critics have not always recognized this repertory’s worth, the curators themselves slight the dances at the heart of this enterprise. Strangely, the catalog also fails to acknowledge the AAADT’s achievements after the founder’s death. Do not search the chronology for subsequent milestones like the opening of the company’s state-of-the-art home, or the premiere of Ronald K. Brown’s Grace.

Edges of Ailey also illustrates the curious position of American artists and intellectuals in a democratic culture that prioritizes material success. Our intellectuals and the public regard each other with mutual disdain. In his foreword to the catalog, Whitney Museum director Scott Rothkopf acknowledges that AAADT’s “broad popular appeal” delayed the troupe’s recognition by high-brow institutions like the Whitney. Does this elitism explain why the current exhibition sidesteps the dances?

Status anxiety erupts spectacularly in the catalog’s use of language. While the exhibition’s text panels address the public lucidly in English and Spanish, readers will find most of the catalog essays written in the hieratic style of a caste of scholar-priests. Don’t forget to bring your Phd decoder ring! Among the best of these essayists, Ariel Osterweis analyzes Ulysses Dove’s ballet Episodes. Intensity underscores the value of each passing moment in Episodes, where the dancers’ virtuosity suggests bravado and defiance in the midst of AIDS. In an affecting memoir, dancer Aimee Meredith Cox describes her personal growth, finding her identity in the abstraction of Ailey’s Streams.

Evidently, the Great Man theory of history is out of fashion; so, Edges of Ailey portrays the choreographer through the filter of Black and Queer society. Yet Ailey’s colleagues recall him as a hero. Pursuing what he described in his notes as a “romantic vision,” and cannily attuned to the taste of the American public, this exceptional artist embraced a life of risk and sacrifice to bring Black bodies and Black culture into the mainstream. He carried hundreds of his fellow artists on his broad shoulders. Now the museum crowd wants to hitch a ride, he’ll carry them, too. Mr. Ailey can carry them all.

Jill Johnston in Motion: Dance, Writing, and Lesbian Life

Jill Johnston in Motion: Dance, Writing, and Lesbian Life

By Clare Croft

Duke University Press

The Essential Jill Johnston Reader

The Essential Jill Johnston Reader

By Jill Johnston, edited by Clare Croft

Duke University Press

Reviewed by Elizabeth Zimmer

These are just such good books; I am boggled by them.

Born in 1929, Jill Johnston was the oldest of the phalanx of female dance writers who turned the field into a matriarchy beginning in the 1960s. Clare Croft, a professor at the University of Michigan, has clearly fallen in love with both Johnston and what she meant to the feminism of the period. Her two recent books document the story of a transformation, of an era Johnston spent in a “bewilderness,” recording and communicating the ripest work of the “dance boom” now behind us, and strategies for living as an “out” lesbian.

As a youngster Johnston, born out of wedlock as a result of an affair her mother had at sea, was sequestered in Queens with her grandmother while her embarrassed mom worked as a nurse in Manhattan. She began dancing in college and came to New York City to study with José Limón, but a broken foot diverted her into writing, first for Martha Graham’s collaborator Louis Horst and then originating dance coverage at the city’s fledgling alternative weekly, the Village Voice.

I basically owe Johnston my career; she carved a niche for dance at the Voice that Deborah Jowitt filled when Johnston moved on to writing about her own life and the political moment. I inherited the editorship of Jowitt and other Voice dance writers at the death of Burt Supree. Johnston’s observation in a 1970 Voice column, quoted on page 35 of The Essential Jill Johnston Reader, shaped my decision to enter the field: “…I never actually realized that dancing is the only organized cultural institution in which women are preeminent; nor that the reason for this is rooted in attitudes toward the dance as a frivolous entertainment in which a lady is encouraged to exhibit her charms, her grace and deportment, her bodily attributes, her seductive powers, in the formally sanctioned theatre of a man’s license for approved general voyeurism.” This sentence comes at the top of a column that occupies more than three entire pages in the Reader, and consists of one paragraph.

Johnston was as enraptured with contemporary art and artists (and poetry: a whole section of Jill Johnston in Motion is devoted to her identification with the work of surrealist Guillaume Apollinaire) as she was with dance. Croft compares her place in American culture with that of Susan Sontag, who was much more circumspect about her sexuality than Johnston.

Anyone who dances, thinks about dance, or writes about dance should read Croft’s book, and simultaneously take to bed the Reader, a collection of Johnston’s legendary pieces. As well as containing in full most of the work that Croft can only reference in JJinM, it has a 31-page appendix listing everything Johnston published from 1957 until 2007, including eleven books and hundreds of articles in places like Louis Horst’s Dance Observer, ARTnews (as many as 18 reviews a month!), Art in America, and the American Poetry Review. Johnston wrote during the golden age of print journalism, when it was possible to earn a decent living with your pen. A literary star who once described herself as “an asteroid,” she was also a political pioneer, a feminist annealed in the ferment of the ’60s and ’70s. Her prose, like her body, was in constant motion; she paid attention to the size and shape of sentences and paragraphs, and her ideas galloped down the page. She’d visit you and hang from the rafters in your loft, interrupt a boring speech by jumping into your pool. At every level, she made news.

Errand Into the Maze: The Life and Works of Martha Graham

Errand Into the Maze: The Life and Works of Martha Graham

By Deborah Jowitt

Farrar, Straus and Giroux

Reviewed by Ellen Graff

In this exciting and evocative new biography, Deborah Jowitt takes us into the maze of Martha Graham’s world. She begins with the earliest influences of family and continues through her experiences with Denishawn, performances in the Greenwich Village Follies, early experiments at the Eastman School, and her first independent choreography. She chronicles the arc of Graham’s choreography, beginning with works inspired by American themes such as American Document and Appalachian Spring, the turn towards literary themes with Deaths and Entrances and Letter to the World, the Greek cycle with dances such as Night Journey, Cave of the Heart, and the epic Clytemnestra, and finally her own role as a creator in the playful Maple Leaf Rag.

Her descriptions reveal a deep understanding of the richness of Graham’s movement, in its force, in its evocation of feeling, and its connections to memory. Describing Letter to the World, she writes, it was “the first dance in which Graham tried to portray in a group work the inner landscape of her protagonist, the first time her heroine relived events or sensations in memory.” With Letter to the World, she continues, “Graham experimented with mingling past and present, the real and the imagined, and [Emily] Dickinson and herself as dedicated artists.” Jowitt has time for humor, too, as she recounts Graham playing Miss Hush on the radio show “Truth and Consequences” and being lampooned in an illustration for a 1934 issue of Vanity Fair.

Errand into the Maze takes the reader on a journey through the cultural landscape of the twentieth century as Graham explored the depths of her own creativity. Through Jowitt’s clear and insightful writing, we come to understand Graham as a force within a wider cultural world, influenced by changing constructs at the same time that she is instrumental in creating change.

Note: Ellen Graff, a former Graham dancer and author of Stepping Left: Dance and Politics in New York City, 1928-1942, once danced with Deborah Jowitt in a work by Pearl Lang. In the 1980s, Graff was a student of Jowitt’s in NYU’s Department of Performance Studies.

The Swans of Harlem

The Swans of Harlem

By Karen Valby

Pantheon Books

Reviewed by djassi daCosta johnson

In Invisible Man, Ralph Ellison’s novel about the ways that racism has colored the Black experience, he writes “I am invisible, understand, simply because people refuse to see me.” The new book, The Swans of Harlem: Five Black Ballerinas, Fifty Years of Sisterhood and Their Reclamation of a Groundbreaking History, is one of the many recent attempts to make visible the unsung accomplishments of Black artists within American culture.

In 2020, writer Karen Valby became privy to a gathering of five Black women in Harlem who began meeting weekly as the 152nd Street Black Ballet Legacy Council. Prompted by the pandemic and the Great Uprisings following the killing of George Floyd, they gathered to remember, share, and celebrate their lives as unsung pioneers in the ballet world.

The women— Lydia Abarca, Gayle McKinney-Griffith, Sheila Rohan, Marcia Sells, and Karlya Shelton-Benjamin—were founding members of the Dance Theatre of Harlem (DTH), the groundbreaking company co-founded by Arthur Mitchell in 1969 as a haven for Black ballet dancers. Grateful for the roads they paved but frustrated by the labeling of Misty Copeland as the “first Black principal ballerina,” they came together to resurrect their stories and ensure that future internet searches for Black ballet dancers would include their accomplishments.

These women have collectively accomplished an epic number of firsts. Abarca, who shone in Balanchine’s Bugaku and Jerome Robbins’ Afternoon of a Faun, was the first Black ballerina to grace the cover of Dance Magazine. Sells was the youngest founding member in the company at 15; after DTH she earned her BA at Barnard, obtained a law degree, and was recently the first chief diversity officer for the Metropolitan Opera. At the age of 17, Shelton-Benjamin was the first Black dancer to represent the United States in the Prix de Lausanne. McKinney-Griffith, an admired lead in Balanchine’s Concerto Barocco and Louis Johnson’s Forces of Rhythm, became the first ballet mistress for DTH. (Sadly, she passed away a few months before the book was published.) Rohan was a mother of three when she was accepted into the company, a fact she kept secret from Arthur Mitchell for a whole year before he found out, telling her, “If I’d known you had mouths at home to feed, I would’ve paid you more!”

Valby respects each of the women’s achievements while uplifting their friendship and sisterhood. We get to feel their pride in being part of a movement larger than themselves, while not sugarcoating the difficulties faced, including the misogyny and verbal abuse under Mitchell that is characteristic of the patriarchal ballet tradition.

Swans lifts the veil of invisibility in a way that makes us ask, “How many more stories have gone untold and undervalued?” The author, along with the Swans, has given birth to an engaging read that brings long overdue attention to these pioneering Black ballerinas.

Behind the Screen: Tap Dance, Race, and Invisibility During Hollywood’s Golden Age

Behind the Screen: Tap Dance, Race, and Invisibility During Hollywood’s Golden Age

By Brynn W. Shiovitz

Oxford University Press

Reviewed by Elizabeth Zimmer

On her book-signing tour, Brynn Shiovitz lectured on the book’s nominal subject, “a theory of covert minstrelsy.” But her actual subject is racism in American popular culture, from the earliest days of sound films until the mid-1950s. A small proportion of her material actually engages tap dancing, mostly revolving around Bill Robinson, who managed never to don blackface.

Shiovitz anatomizes the phenomenon of blackface as it migrated from the stage to the screen and from live performance to animated cartoons. She points out that the original “minstrels” were white men in blackface. Black people, often forced to “black up” by theatrical promoters, got into it to make money. She shows how blackface is associated with a kind of nostalgia that denigrates African Americans.

The author grew up tap dancing, studied at NYU and UCLA, and teaches in Southern California. She spent years screening 230 films to demonstrate the way that Bing Crosby and Fred Astaire coasted to fame, replacing the true Black masters of the Africanist esthetic. Also under her microscope are brownface, yellowface, redface, and Jewface, all strategies Hollywood used to “other” immigrant groups (as well as Native Americans). The denigrating aspects of blackface, which reduced an entire group of people to caricature, slipped under the radar of the Hayes Code of 1930, which was supposed to regulate the moral tone of popular entertainment.

The Catholic Church, the engine behind the Code, aka Motion Picture Production Code, demonized Black art forms like jazz and swing. This allowed white people to rip off the Africanist esthetic while Blacks were often deprived of credit, even when they appeared onscreen. Jazz music was painted as a slippery slide in the direction of sin. Blacks incarnated these things, were “tricksters,” and needed to be kept separate from white wives and daughters.

Both the visual and the sonic—and the animated as well as the “real”—were environments to be carefully monitored for implications of racial mixing. As Shiovitz notes, this rendered whites “the celebrated ventriloquists of an Africanist esthetic,” providing American audiences with a “close but safe encounter with the Other.” It also suppressed any representation of gayness (“pansy flavor”) and much female sexuality, but gave a pass to figures like Al Jolson and Eddie Cantor, Jewish men who accrued fortunes and fame pretending to be Black.

Dance and film scholars and others awake to the damage of racism will find much value here. Those of us who escaped graduate school before the theory bomb exploded might find the proportion of her analysis devoted to tap dance a bit wanting, but younger readers might appreciate her deep dive into Bugs Bunny’s “techno-dialogic feats for the animated bestiary.” Animation technology, she asserts, replaces blackface in live action films of the early ’40s: “Much of what the [Hays] Code deemed unacceptable in live action film for the censors was excused when the representation was not ‘real.’” Shiovitz’s flaying of the racist content of American popular art forms in the 1930s and ’40s will change the way these works are viewed in the next millennium.

A longer version of this review appeared in 2023 here.

Simone Forti: Improvising a Life

Simone Forti: Improvising a Life

By Ann Cooper Albright

Wesleyan University Press (discount code Q301 for 30% off)

Reviewed by Wendy Perron

This “review” is based on my endorsement blurb on the back of the book:

Simone Forti is a pioneering dance improvisor who crosses genres in ways that have opened up new possibilities. Ann Cooper Albright brings her own poetic insights to her subject in this beautifully written book, giving a deep sense of the deceptively simple, shape-shifting artist. It’s also a celebration of the kind of category-defying dance artists that abounded in the 1960s. The author has witnessed many Forti performances around the country, and she has quoted from Forti’s essential writings as well as from other sources (including my own essay). The reading experience is a contemplation that connects mind, body, and spirit. Many revelations, small and large, await the reader.

Pilobolus: A Story of Dance and Life

Pilobolus: A Story of Dance and Life

By Robert Pranzatelli

University Press of Florida

Reviewed by Robert Johnson

Dartmouth College, where Pilobolus debuted in 1971, was an unlikely birthplace for a dance company. Yet the unsettling spirit of the 1960s had infiltrated the Great North Woods. The radical times, as much as the place, enabled three youngsters in Alison Chase’s dance composition class—initially Moses (Robert) Pendleton, Stephen Johnson, and Jonathan Wolken—to pursue a wayward artistic vision. If Martha Graham’s dancers are the acrobats of God, then Pilobolus’ are the children of a peculiarly American Eden.

Robert Pranzatelli tells this tale well in Pilobolus: A Story of Dance and Life. At times, this author’s allegiance to the company gets in the way of objectivity, and he seems unaware of Pilobolus’ relation to the rest of the dance world. Yet he has made excellent use of unpublished material and has conducted many interviews enabling the artists to share their perspectives.

Given Pilobolus’ collective decision-making, the narrative often revolves around the dueling personalities who left their imprint on the work and left emotional bruises on each other. Yet Pranzatelli also describes those wonderful creations Alraune, Shizen, Pseudopodia, Untitled, and Day Two. A wise editor might have advised the author to cut the fan-boy passages and write more about the choreography.

Though he gamely signs up for movement workshops, Pranzatelli isn’t really a “dance person,” so it would be difficult for him to explain why Pilobolus ever felt the need to prove its pure-dance credentials with Sweet Purgatory (1991). He does not seem to appreciate that collaborating with Butoh artist Takuya Muramatsu is qualitatively different from collaborating with commercial choreographer/filmmaker Trish Sie; and Pranzatelli doesn’t see how the company’s technological experiments dovetail with larger trends. Enchanted by the company’s calendar art, he finds its essence in “wit and physical sensuality,” not in movement or design.

More happily, sparked by Pendleton’s idea that the history of Pilobolus is the history of America, Pranzatelli emphasizes the role of 1960s counterculture in shaping the company’s aesthetic. We read of free love, encounter groups, and “buttery baked soy logs.” Waving fields of marijuana plants give way to teddy bears stuffed with sacramental vegetables, and the dancers frolic naked in the rain. More could be made of the parallels between these hijinks and the tradition of American utopianism. The estrangement of the company’s founders is the fate of Hawthorne’s fictional Blithedale colony with bare asses.

What happened next is cautionary. Within a single lifetime, the America of “Alice’s Restaurant” gave way to the America of The Big Short, and Pilobolus seems to have become greedy. Techno-chic and vapid commercialism threatened to supplant the heroic, human-centered art of the early years. Yet the company’s core values were not so easy to discard. Pilobolus failed when it tried to sell out; and, since then, as executive and co-artistic director Renée Jaworski says, the troupe has been obliged to consider “where to hold onto…the quaintness of not being part of a giant, corporate entity.”

Five Ballets from Paris and St. Petersburg

Five Ballets from Paris and St. Petersburg

By Doug Fullington and Marian Smith

Oxford University Press

Reviewed by Mindy Aloff

Before “less is more” took hold as the mantra for art in the twentieth century, there was the goes-without-saying assumption that, as in Nature, more is more. The spectacles of nineteenth-century ballet, especially in France and Russia (whose ballet traditions were developed under strong French influences, imported by French choreographers going back to Jules Perrot, in the early 1850s) were built on this elemental basis.

In addition to actual body-to-body and brain-to-brain transmission of a ballet’s identity, the indispensable aide-memoires that made it possible for one or two individuals to transplant, say, Giselle’s medieval Germanic world onto the post-Romantic imperial theater of the tsar—and for régisseurs in ensuing decades to preserve at least enough of the work to maintain the just use of the title as new casts and crews came in—were written languages of notation. It is the contention of the authors of this astounding volume—a treasury of research, observation, and reasoning—that those languages not only can be read today in archival documents but must be for anyone who seeks to comprehend what made nineteenth-century ballet both magnetically popular and great art. This book—well-spoken, logically structured, gracious, and most experienced—will function as the sherpa for readers who even contemplate learning how to read and compare Stepanov’s notation against Justamant’s notebooks and then apply what they have learned to current productions of nineteenth-century ballets.

The five examples, all once choreographed in whole or in part by Marius Petipa—the Frenchman whose legacy overwhelms the story of ballet in Russia—are Giselle (on whose history Smith is considered to be an authority), Paquita, Le Corsaire, La Bayadère, and Raymonda. Fullington, mentored by Smith during his doctoral work at the University of Oregon, is a practiced reader of Stepanov notation. He and Smith collaborated with Peter Boal on Pacific Northwest’s Ballet’s historically informed production of Giselle and on PNB’s upcoming new production of The Sleeping Beauty. Fullington has also collaborated with Alexei Ratmansky on productions of the other four ballets, all recorded in Stepanov.

In the course of Five Ballets, Fullington and Smith make passionate cases for bringing back pantomime, character dancing, minor characters, faster tempos, and the tiny beaten and skimming steps those tempos once served, and, most of all, stage recreations of Nature in all its haunting and mysterious guises. Their book also acknowledges aspects of nineteenth-century productions they would prefer not to restore—racism, anti-Semitism, mocking of the aged. It’s a surprise to discover that August Bournonville—Petipa’s great contemporary in Denmark—is not even mentioned in the index, since his ballets—also spectacular and bursting with petit allegro, character dancing and so forth—appear to have evaded some of the more disagreeable aspects of ballet in the nineteenth century. The subject of another volume, perhaps?

Dance History(s): Imagination as a Form of Study

Edited by Thomas F. DeFrantz and Annie-B Parsons

Wesleyan University Press

Reviewed by Morgan Griffin

They say, “Don’t judge a book by its cover,” but forgive me, because before I have even unpacked this set of books I already love them: a collection of pastel booklets, with contrast colored string binding, parceled together by a thick bright turquoise rubber band. The introduction by Thomas F. DeFrantz outlines the proposal at hand, which he introduces as seemingly impossible. “After all,” he writes, “We make dances that vanish even as they materialize.” How to collectively decide what histories and stories matter most? How to write down something that is indescribable, maybe even forgotten?

In the following short stories, thirteen choreographers, dancers, movers, humans outline their versions of “dance history.” Each takes a different approach and form, yet almost all arrive at very similar conclusions. DeFranz describes a futuristic world, where dance and human connection live only via virtual platforms. Ogemdi Ude writes exclusively of her relationship with majorettes. Mayfield Brooks tells a fable about the beginning of time, and the early connections between plants, animals and humans as it relates to dance. Creating a kind of Lord of the Rings of dance, Annie-B. Parsons shares a pictorial chronicle of her dance history. Keith Hennessy’s account broke my heart and simultaneously healed it. Bebe Miller writes on personal moments in time that have shaped her, while struggling with how to “remember remembering.” I find each little book captivating, in both its writing and its form. The words and images are like choreography, and as a reader my eyes and fingers move in a dance across the pages. I find myself clutching my heart, nodding my head, exclaiming out loud…dancing.

Despite their differences, there are many ideas that recur throughout the series: dance as ritual, dance since the beginning of time, the dance of nature, the idea of memory, lists of choreographers who inspired each author (many overlapping), the importance of human contact, human gathering, community, and the passing down of dance through embodied practice. The most striking similarity perhaps is the inability to capture the history of dance at all. Maura Nguyên Donohue writes that “The struggle with writing a dance history is a struggle with time.” And there seem to be even more struggles to follow. Who decides what is important? Andros Zins-Browne rightfully claims that dance histories are inevitably more about the authors who write them, than the dances themselves. How can you write the unwritable? After seeing an influential performance, Okwui Okpokwasili writes, “I can’t find a single word for what I am witnessing or what is happening in my body.” How can you capture a history that is ever evolving? History is now. Similarly, “dancing is living.” And so the task at hand remains beautifully impossible. These small pastel books are more like love letters to dance, to our dancestors, to our dance community, to the never-ending struggle, to the magic, to the impossibilities, to the now. Dance history remains indeterminable. Memory is fleeting and fickle. Dance is extremely personal. Dance is inherently universal. Dance is impossibly indescribable. And yet dance is forever.

Books received or announced

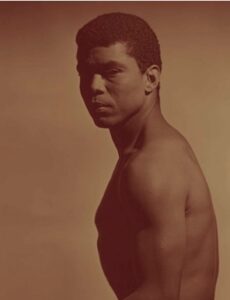

Body Impossible: Desmond Richardson and the Politics of Virtuosity

By Ariel Osterweis

Oxford University Press

Body Impossible theorizes the concept of virtuosity and queer Black masculinities in contemporary dance through a study of the career of dancer Desmond Richardson.

The Simonson Legacy

By Jeanne Donohue

BookBaby

A coffee table biography of Lynn Simonson, creator of Simonson technique, which incorporates somatic practice in the teaching of jazz dance.

Meredith Monk: Calling (exhibition catalog)

Edited by Anna Schneider, Beatrix Ruf, Peter Sciscioli, Haus der Kunst, München, Hartwig Art Foundation.

Essays about the work of national treasure Meredith Monk. Contributors include Hilton Als, Bonnie Marranca, Meredith Monk, Louise Steinman, Björk, Carla Blank, Theo Bleckmann, Ping Chong, Ellen Fisher, Katie Geissinger, Ann Hamilton, Lanny Harrison, Pico Iyer, Joan Jonas, Alex Katz, John R. Killacky, Ralph Lemon, Bobby McFerrin, Bruce Nauman, Shirin Neshat, Ishmael Reed, Alex Ross, Peter Sciscioli, Anne Waldman, and John Zorn

Hatje Cantz

Dancing the Afrofuture: Hula, Hip-Hop, and the Dunham Legacy

By Halifu Osumare

University of Florida Press

Osumare’s earlier memoir, Dancing in Blackness, was chosen as the lead book in our Notable Dance Books of 2018. About the current book, Library Journal says this: “Osumare gives readers a deeply personal look into her world as a dancer, choreographer, scholar, professor, activist, and all-around powerhouse. . . . Part self-reflection and part love song to Dunham, this book is a triumphant look at a dancer’s second act as a scholar.”

Artists on Creative Administration: A Workbook from National Center for Choreography

Edited by Tony Lockyer

University of Akron Press

Core Connections: Cairo Belly Dance in the Revolution’s Aftermath

By Christine M. Sahin

Oxford University Press

“Investigates marginalized women’s corporeality as a complex site of power as it takes readers through a diverse dance landscape spanning from Nile cruising tourist boats to Pyramid Street cabarets.”

Balanchine and Me: Be Relevant, Not Reverent

By Peter Martins

Academica Press

Fraught Balance: The Embodied Politics of Dabke Dance Music in Syria

By Shayna M. Silverstein

Wesleyan University Press

From the back of the book: “The author shows how dabke dance music embodies the fraught dynamics of gender, class, ethnicity, and nationhood in an authoritarian state.”

Kinethic California: Dancing Funk & Disco Era Kinships

By Naomi Macalalad Bragin

University of Michigan Press

From the website: “Explores the making of black social and vernacular dance in the 1970s, precursor to today’s global hip hop/streetdance culture.”

Performing the Greek Crisis: Navigating National Identity in the Age of Austerity

By Natalie Zervou

University of Michigan Press

Quoting Ann Cooper Albright: “The beginning focus on the ‘body in crisis’ is a powerful entry point into a discussion of contemporary Greek dance, a topic that warrants more exposure within an international context.”

Leave a Reply