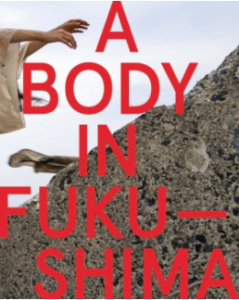

It’s a strange, unsettling thing, but disaster can be visually beautiful. In a monumental new book called A Body in Fukushima, Eiko Otake is photographed in Fukushima, the site of the 2011 tsunami-prompted nuclear meltdown, by William Johnston. These images of a lone figure in irradiated danger zones are imbued with an elegiac quality. Containing 160 color photos, the book traces the long-term collaboration between Eiko, the dancer of Eiko & Koma fame, and Johnston, the photographer who teaches history at Wesleyan. From 2014 to 2019, the two made five trips to Japan, visiting a total of 26 once-populated places in and around Fukushima, some of which are now ghost towns. I am writing now, during the week of commemorating the 1945 bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, to say why this book haunts me.

It’s a strange, unsettling thing, but disaster can be visually beautiful. In a monumental new book called A Body in Fukushima, Eiko Otake is photographed in Fukushima, the site of the 2011 tsunami-prompted nuclear meltdown, by William Johnston. These images of a lone figure in irradiated danger zones are imbued with an elegiac quality. Containing 160 color photos, the book traces the long-term collaboration between Eiko, the dancer of Eiko & Koma fame, and Johnston, the photographer who teaches history at Wesleyan. From 2014 to 2019, the two made five trips to Japan, visiting a total of 26 once-populated places in and around Fukushima, some of which are now ghost towns. I am writing now, during the week of commemorating the 1945 bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, to say why this book haunts me.

In these photographs in the evacuation zone, Eiko’s body absorbs the desolation of these places. One can read sadness, fear, loneliness, courage, protectiveness, resistance, or resignation in her face and body.

Eiko in Yamadahama Seawall, all photos by William Johnston

Visually, she is inseparable from the landscape. She blends in with the rocks at Yamadahama. She clutches her waist amidst big plastic bags full of radioactive debris in Namie Town. She kneels, perhaps in prayer, on Shinmaiko Beach. She stands huddled against the wind in front of a shuttered Yamaha store in Namie Town. Among the tangled wires of Tomioka Sanitation Plant, she grabs her red silk cloth (re-sewn by her mother and herself each time it rips from her dancing). She reaches upward for a hanging bell rope at Shiogama Shrine. Each scene opens a window into the possibility of story.

At Shiogama Shrine

The book also contains essays by Eiko that are eloquent, pained, and brilliant in their determination to understand suffering. In a piece called “Movement,” she connects body movement to the movement of a virus to political movements like Black Lives Matter. She’s a thinker/writer/artist who has been studying atomic bomb literature for twenty years.

In Hittachi Benten

The gravitational pull Eiko feels toward Fukushima is explained in a letter to her deceased friend, Kyoko Hayashi, a survivor of the Nagasaki bombing and author of From Trinity to Trinity (translated by Eiko). There is some part of Eiko that seeks to be in sisterhood with Hayashi, to understand what it feels like to be a hibakusha, a survivor of the nuclear holocaust. In Eiko’s dancing for Johnston’s camera, she wants her body to know and remember, and to share that knowing with us.

The aim here is to resist forgetfulness — and you see that in Eiko’s body. You see how her body is weighed down with remembering. In these god-forsaken locations, she exudes a fully alive response to place. And yet, as Eiko said in the recent Poetics of Aging panel, “Part of my work is preparing to die, or at least practicing to die . . . improvising.”

In the “Afterword,” Eiko compares the disaster of the current pandemic to the disaster of Fukushima: “A nuclear plant or a great city—everything humans make is breakable. We are breakable. All are fragile. We know this now more clearly than ever.”

When I used the word “monumental” earlier, I meant it in several ways: A Body in Fukushima, published by Wesleyan University Press, is artistically, emotionally, historically, globally, environmentally huge. It is monumental not only for positing grieving as a source of art, but also for recognizing the colossal recklessness of human civilization. This beautiful book, which is available at an affordable price due to funding from the Duke Foundation, is a warning.

Shinmaiko Beach

Note: To mark the anniversaries of the bombing of Hiroshima (August 6, 1945) and Nagasaki (August 9, 1945), Eiko performs a site-specific work, They did not hesitate, in association with the Art Institute of Chicago, on Aug. 7.

Featured Leave a comment

Leave a Reply