I had grown up studying—and loving—both modern dance and ballet. But they were two separate worlds. When I saw the Robert Joffrey Ballet in Central Park in 1963, it was love at first sight. Their repertory was contemporary within classicism: The dancers cut sharp angles in Brian Macdonald’s Time Out of Mind (1963), and they stretched and curled on the floor (the floor—in a ballet company!) in Gerald Arpino’s Sea Shadow (1962). So I started taking classes at their school in Greenwich Village and kept that up for my last two years of high school. In those days you either committed to a ballet company by 18 or you forsook ballet and went to college. I was torn. For months. Finally I decided to go to Bennington College.

After graduating in 1969, I was on scholarship at the Martha Graham school and dancing with the nexus of choreographers at Dance Theater Workshop—Rudy Perez, Deborah Jowitt, Kathryn Posin, Jack Moore—and was making dances too. I was also taking Maggie Black’s ballet class. Maggie’s studio was the only place where modern and ballet dancers were in the same room. (Attending Maggie’ classes was also Kevin McKenzie, who had seen Deuce Coupe when he was with the Joffrey and is now director of ABT.)

When I saw The One Hundreds (1970) I was enthralled. I’d never seen dancing that was so polymorphous. My eyes were glued to Sara Rudner, Twyla and Rose Marie Wright as they powered through (or poured through) impossibly complex movement skeins. These were 100 eleven-second segments done in unison and in silence. The sheer inventiveness of the movement — within the ebb and flow of advancing forward while dancing and walking back upstage—was overwhelming.

So, in January of 1972, when Twyla formed the farm club in Tribeca (this was her second one, the first was on a real farm in Vermont), I was totally up for it. The melding of full-out movement with ordinary gesture, the constant shifting of where an impulse would spring from, the conscious physicality that was demanded—these were just the stimulation I needed. The rest of that year I choreographed, danced, and taught.

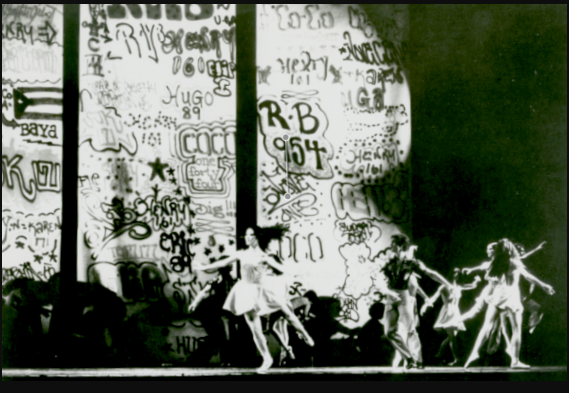

And then Deuce Coupe happened. That much pleasure onstage seemed like it must’ve been illegal. It broke all the rules, starting with the separation of ballet and modern dance. Twyla’s six amazing dancers mingled onstage with the eleven Joffrey dancers. The Beach Boys music was sensuous, fun, and sassy—a bold choice, given that choreographers were cautioned against using popular music because of its familiarity. The set design was a group of graffiti writers from the Bronx spraying their memes—with names like Coco 144, Snake 1, Stay High 149, Riff 170, and Bug 170—on a scroll upstage. We tend to forget how revolutionary this was, both for the fact that live people were creating the set and part of the set (although Robert Rauschenberg, collaborating with Merce Cunningham, had devised a set of living, moving people, and Charles Ross had done that at Judson Dance Theater as well as for Anna Halprin) and for challenging the privileging of ballet for and by the elite. Graffiti was not widely considered art those days, but Twyla was an expert at rupturing the status quo.

The original Deuce Coupe in 1973

The vivid personalities of Twyla’s dancers emerged despite their nonchalant style. Twyla herself tore through space with unstoppable determination. Sara’s luscious, intelligent sensuality was heaven-sent. Rose towered above all with a good-natured athleticism.

The Joffrey’s Erica Goodman at left, Tharp’s Isabel Garcia-Lorca at right.

The Joffrey’s Erica Goodman played the part of a beacon of “purity,” executing tendues and other steps in the ballet alphabet with precision.

In the “Cuddle Up” finale, all these elements mingle, eventually forming one ribboning line of movement. At this point the graffiti canvas has scrolled upward, filling the upper regions of the stage with dense and chaotic design. Tharp made all the parts flow together, and because, in my world they had been separate, it was moving to behold. Ballet, modern, pop music, and the urban form of graffiti all mixed together. It was, I believe, the first of Twyla’s everything-all-at-once endings—and a vision for a possible ideal world.

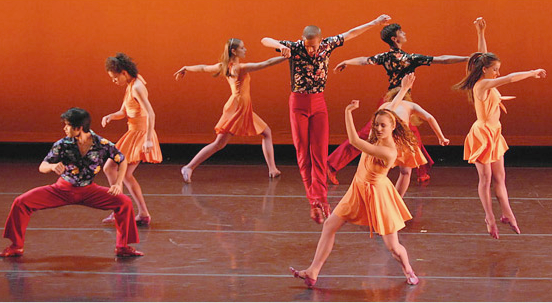

The Juilliard production of Deuce Coupe in 2007

This week American Ballet Theatre is performing its first Deuce Coupe. Back in 1973, it wouldn’t have gone near this little rock’n’roll ballet. Deuce Coupe was a specialty of the Joffrey, part of what made that company so American. Later it migrated to Kansas City Ballet, where artistic director William Whitener brought it to life. (Bill was one of the Joffrey dancers in the original cast who was so beguiled by this new way of moving that he soon joined Tharp’s company.) It’s also been done by Juilliard students and other companies. But all the later versions had to be practical: only a static backdrop and a cast of only ballet dancers.

Deuce Coupe is still a landmark ballet. You can see how Tharp creates harmony from very different elements. Gia Kourlas has a nice interview with Twyla, Sara, and two of the ABT principals who will perform it. But, to my eyes, the 1973 version, with the frisson of ballet and modern dancers together onstage and the live graffiti-in-the-making, was the most exciting version.

Featured 4

I thoroughly enjoyed reading your tour through ‘Deuce Coupe,’ intertwining personal history with dance history. Thank you for writing this, Wendy.

So looking forward to reading this marvelous new book by Wendy Perron, and remembering the delighted shock of learning “Continuous Project Altered Daily” in a summer workshop in D.C.by Yvonne Rainer while home from college. Not to mention the great privilege of dancing in a 24 hour performance in NYC directed by Wendy in the mid-seventies when I was on the dance faculty at Cornell. Such a thrilling mix of embodied practice and intellectual and affective responsiveness! The book will no doubt capture this mix perfectly as only Wendy’s writing can. Thank you for all the hard work writing and researching that went in to this book–a critical contribution to dance studies–we need these visions of creative inspiration especially now!

And I remember the great conversations you and I had while working on that crazy 24-hour piece for the Winter Solstice.

Thank you Wendy. Your writing* is a treasure to savor. Wait, can you savor a treasure?

It’s * art in and of itself.