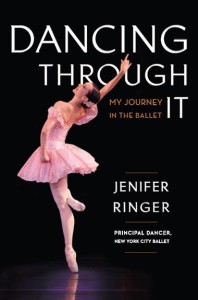

There’s a moment in Jenifer Ringer’s book, Dancing Through It: My Journey in the Ballet, when she is so desperate that she contemplates suicide. She’s tried again and again to solve her eating disorder, which led to losing her job at New York City Ballet, and she feels like an utter failure. What saved her, in that dark moment, is the awareness of the pain her death would bring to her parents and sister. Needless to say, one of the reasons to read her terrific book is to learn how she pulled herself out of that abyss.

I know, from the suicide attempts of people close to me—both successful and blessedly unsuccessful—that what goes out the window in those darkest moments is any thought of one’s loved ones. (Or, in temporary twisted thinking, the notion might be, “They’d be better off without me.”) Every thought crowding around the person is simply, and only, about how to release themselves from a life that has become unbearable.

Philip Seymour Hoffman

In Michael Feingold’s recent column in Theater Mania, he comes to a similar conclusion. Prompted by the death of actor Philip Seymour Hoffman, he is trying to understand the addictive personality. He contrasts that type of person with artist in the theater who have lasted a long time, giving the example of the 90-year-old lyricist Sheldon Harnick. Of course, addiction is complicated and an overdose such as Hoffman’s may be accidental. But in general, Feingold sees that, at the other end of the tunnel, there needs to be some feeling that you matter to those close to you. If there is a secret to survival, he says, it is “the simple awareness of others’ concerns.” Sadly, that awareness is sometimes beyond the reach of someone who’s been pulled into a downward spiral.

Depression has long been a hazard for artists. I found this in Tchaikovsky’s letters, from 1876:

Tchaikovsky

“Sometimes for hours, days, weekends, months, everything looks black; it seems that you are abandoned by everyone, left alone, and no one loves you. But I explain my state of despondency, my weakness and sensitivity, by my bachelor state and absolute lack of self-denial. To tell the truth, I live following my vocation as well as I can, but without being of any use to individual people. If I should disappear from the face of the earth today, maybe Russian music would lose something—but surely no one would be made unhappy. In short, I live the egoistic life of a bachelor. I work for myself, think only of myself, aspire only for my own welfare. This is very convenient, but it is dry, narrow, and deadly.”

Featured 1

I was very, very moved reading this thoughtful reflection.

With regard to Tchaikovsky’s statement that his despondency occurred as a result of “my bachelor state,” I could not help but wonder if this depression was brought about by a society that had taught him to hate himself for being gay. (Perhaps this is too much of a 21st-century read on a 19th century attitude….but never underestimate the ability of internalized homophobia as an insidious force driving self destruction. )