It wasn’t a dance performance. It wasn’t a music concert. It wasn’t an art exhibit. But Work/Travail/Arbeid combined elements of all three to create a rousing, immersive experience.

Anne Teresa De Keersmaeker took her magnificent Vortex Temporum, to the late Gérard Grisey’s gorgeously textured music of the same title, and stretched it out over five days, six or eight hours a day, for the installation at the Museum of Modern Art from March 29 to April 2.

Work/Travail/Arbeid, MoMA, photo © Julieta Cervantes

Her original Vortex Temporum, which was a smash hit at BAM’s Next Wave Festival last fall, sent dancers and musicians careening around in crazily intersecting orbits. It was such a tour de force that it topped my “Best of 2016” list.

I was skeptical that this choreography, now broken up into many parts, could generate the excitement of the original stage piece. But it did—even more so because of the unpredictability of being in the museum environment. Grisey’s “spectral” music, as performed by seven members of the band Ictus, filled the second-floor Marron Atrium. On entering the museum, one could hear the plaintive sighs, the ominous washes of sound, the fairytale plucking sounds, coming from above.

Rosas dancer, MoMA, photo © Julieta Cervantes

Once inside the Atrium, you were swept up at peak moments by dancers from Rosas, De Keersmaeker’s company, dashing around, activated either the chalk circles on the floor or by the soundings of a specific instrument. Or you might be sitting in the path of the piano as it came rolling along its arc.

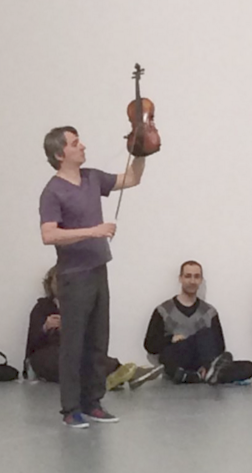

Violinist of Ictus, at MoMA, photo by WP

In quieter moments, you could see the curiosity of the dancers and the musicians about what their instruments could do. A single male dancer seemed to be impulsively speeding up and slowing down, winding into and out of intricate knots of movement, loosely following the circles drawn on the floor. Meanwhile the violinist reversed the usual action: He held the bow steady while lifting and lowering his instrument to contact the bow. Sometimes the wind players just blew into their reeds.

Grisey wanted to both expand and condense the experience of time and space. He wrote that his three temporal modes were “the time of humans…the time of whales…and the time of the insects.” The MoMA brochure explains these as “relating to breathing and heartbeat…a sense of expanded time…a sense of contracted time.” Likewise the dancers expanded and contracted space. Sometimes they loped around in large, carefree circles, other times they made circles within their own bodies, corkscrewing in place with flashes of furious energy.

The interplay between dancers and musicians became more intimate, more in-you-face, than it had been at the opera house at BAM. I’ve never felt the heartbeat of dance in a museum the way I did with Work/Travail/Arbeid.

Rosas dancers re-drew the chalk circles every hour at MoMA, photo @ Julieta Cervantes

The stimulating crossover of sound and movement, listening and watching, caught people’s attention. As curator Ana Janevski said while introducing a talk between De Keersmaeker and MoMA’s associate director Kathy Halbreich on March 29, an exhibit’s success is too often measured by the numbers of viewers who show up. But a better measure may lie in the quality of attention paid. And for Work/Travail/Arbeid, people were captivated.

From above, MoMA, photo © Julieta Cervantes

The sense of interdisciplinary contagion, of energy whipping through the dancers’ circles and musicians’ circles, and the visibility of fellow visitors as part of the configuration, part of the show, contributed to the attraction. So did the knowledge that these dancers, who sometimes had to thread their way through the crowd, have been at it for hours.

Endurance has long been a signature of De Keersmaeker’s work. As she said at the MoMA talk, doing something for a long time changes the body. Halbreich described the endurance of the dancers this way: “Exquisite precision gives way to exquisite fragility.”

De Keersmaeker dedicated the MoMA performances to Trisha Brown, who died just before the run. (Here is my farewell to her.) It’s easy to see the affinity. They both have a faith that formal elements can stand alone, without the overlay of narrative, character, or theatricality. And Trisha’s work has always fit comfortably in museums, in terms of both artistic milieu and design. One could say Trisha did lines and Anne Teresa did circles. Both of them have taught us how to see. And with Work/Travail/Arbeid, we also learn about hearing.

Featured Leave a comment

Leave a Reply