This was the first year that Dance Magazine Awards has given posthumous awards. After all, there are many worthy dance professionals who never were recognized in this way. (The list of past recipients is here.) For the 2023 awards event at the 92nd Street Y on Monday, December 6, I was asked to “present” these honors. This is what I said (with added links):

I’ve been so immersed in dance history, both in my teaching and in my writing, that for me, these four artists, are still very much alive.

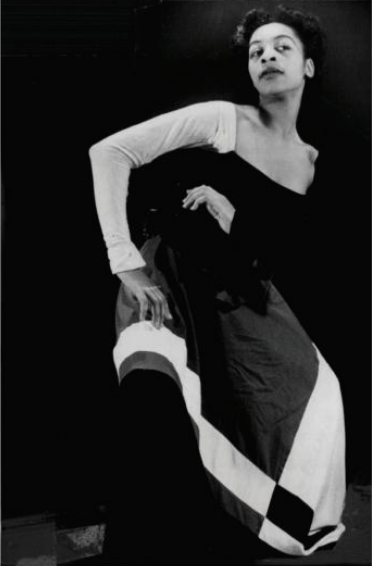

Syvilla Forte (1917-1975)

Like many Black girls who fell in love with ballet, she could not find a teacher in Seattle who would accept her into a class. But at 15, she was given a full scholarship to the Cornish School of Allied Arts, where she encountered a fellow student named Merce Cunningham and a music teacher named John Cage. When she asked Cage to compose music for her with an African inflection, his solution was the prepared piano—which developed into one of his most famous compositions.

After graduating, Syvilla went on to dance with Katherine Dunham—and you can see her for a split second in this clip of Stormy Weather (go to 2 mins, 10 seconds in). Because she’d been turned away from ballet schools, she had a dream of a school where everyone was welcome. So when Dunham opened her school in New York City in 1945, the role of director and top teacher naturally went to Syvilla. She taught the Dunham technique, but when she opened her own school, she evolved it into what she called Modern-Afro Technique, which she felt was a freer form. She became such a beloved teacher that the Black Theatre Alliance organized a gala tribute to her in 1975, when she was ailing with cancer. Harry Belafonte, whose wife Julie had been Syvilla’s student, said, “More graciously than almost anybody else I know…she made one of the most powerful contributions to the field of dance, to the field of theater.” Alvin Ailey called her “our inspiration.” There’s more on Syvilla Fort here.

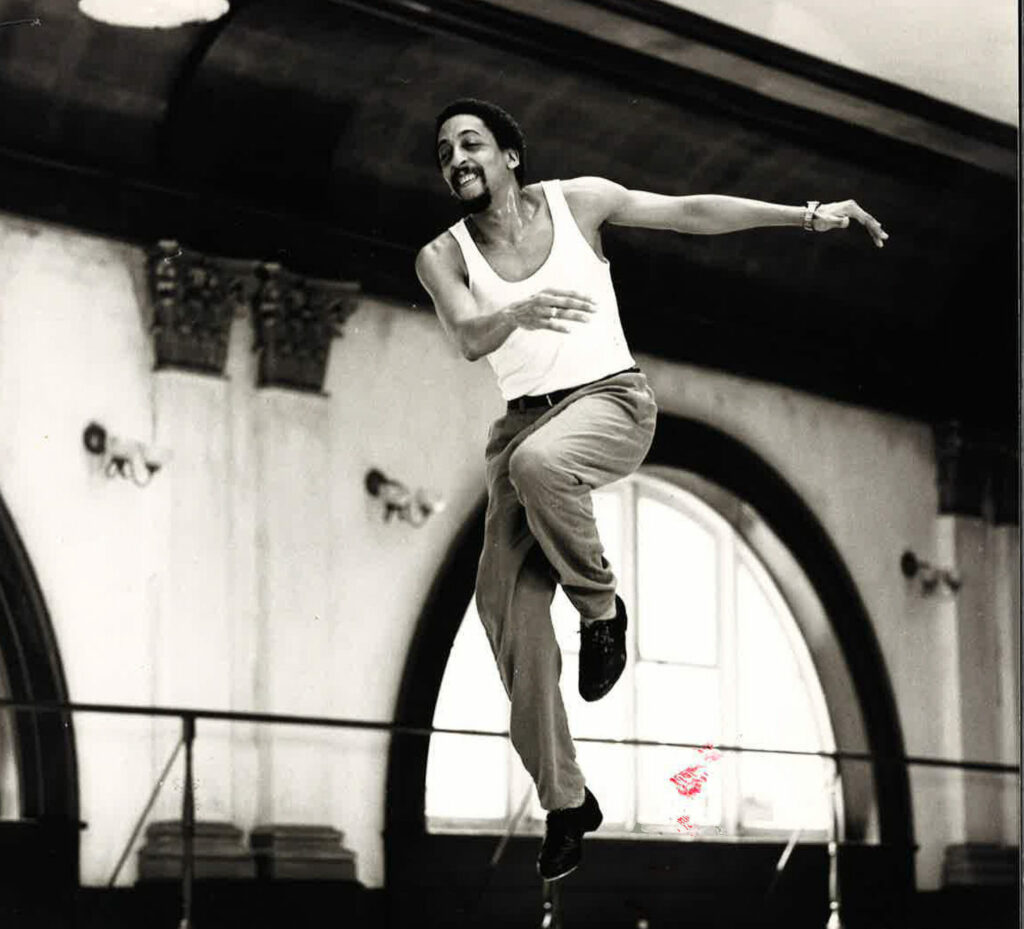

Gregory Hines (1946-2003)

Gregory Hines was a child tapper, professional by the time he was 5. He and his brother Maurice worked up a vaudeville act that took them around the country. The brothers practically grew up at the Apollo, where they saw tap greats like Honi Coles, the Nicholas Brothers, and Teddy Hale. Their childhood act led to television appearances and roles for Gregory in the musicals Eubie! (1978), Sophisticated Ladies (1981) and Jelly’s Last Jam, (1991) for which he won a Tony. He was in many films, and you can see the Hines brothers dance together in this great scene from The Cotton Club (1984). And who can forget the exhilaration of Hines and Baryshnikov, two competing virtuosos, in White Nights?!? (1985)

Dance historian Sally Sommer wrote the best description of his dancing in the New York Times: “Gregory Hines was a gracious and charming performer onstage… But he was also a dance revolutionary who took the upright tap tradition, bent it over and slammed it to the ground…. He recast the image of the black male tap-dancer and roughed up the rhythms…He obliterated the tempos, throwing down a cascade of taps like pebbles tossed across the floor.”

Hines was an influence on many tappers including Savion Glover, Dianne Walker, and Jason Samuels Smith, all of whom have received Dance Magazine Awards. He was also a lifetime advocate, lobbying in Washington to help establish the National Tap Dance Day.

In this interactive essay for Jacob’s Pillow, Brian Seibert discusses why Hines never smiled when he danced, how improvising was a mode of conversation, and his musical mind. Best of all is a clip of him dancing/entertaining at the Pillow Gala of 1996.

Pearl Primus (1919-1994),

The Trinidad-born dancer/choreographer, anthropologist, and educator, was a magnetic performer with a fantastic jump. She debuted her choreography here, at the 92nd Street Y in 1943 and performed here every year for the next decade. She also appeared in nightclubs, rallies in Madison Square Garden, union meetings, and colleges, and later, she picked cotton with sharecroppers in the South. Her trip to Africa in 1948 was transformative for her. Especially in the villages of Nigeria and Liberia, she was welcomed as an ancestral spirit and learned their dances.

She spoke out against the racism of the Jim Crow South and danced for leftist and communist organizations, incurring the watchful eye of the FBI, which at one point confiscated her passport. But she never wavered from her mission to present Black heritage onstage with dignity.

Before all that, she went to Hunter College, and her first modern dance teacher was actually another student at Hunter who had started a modern dance club. This other student spotted her talent immediately and told her, You should go to the New Dance Group. The reason I know this, is that that other student was my mother.

When interviewed in Dance Magazine, November 1968, Primus said she wanted to “reach beyond the color of the skin and go into people’s souls and hearts and search out that part of them, black or white, which is common to all.” Primus’s legacy lives on with Philadanco, which holds in its rep, her solo Strange Fruit (one of my choice of Iconic Short Solos), depicting a horrified response to a lynching. And Urban Bush Women have paid tribute to her with Jawole Willa Jo Zollar’s intense, overwhelming work, Walking with Pearl.

Read John O. Perpener’s interactive essay on Primus in Jacob’s Pillow’s Dance Interactive here.

Helen Tamiris (1905–1966)

A force in the New York dance world from 1927 to 1964, was a bold, sensual dancer who choreographed more than 90 pieces for the concert stage. Her performances had a warmth and accessibility that were different from the works of her more strictly modernist peers. Always community minded, in 1930 she organized a cooperative venture with Martha Graham, Doris Humphrey, and Charles Weidman so that the four groups could perform on Broadway at an affordable cost. During the Depression, when President Roosevelt established the Works Progress Administration to keep people working, it included the Federal Theater Project, and Tamiris lobbied for dance to be part of it. Her signature work How Long Brethren (1937) was the longest running show to come out of the Federal Dance Project. Performed to Black spirituals, it depicted scenes of Black oppression and poverty— (usually with a white cast, and that has fostered some current controversy.)

Tamiris also choreographed 18 Broadway musicals, including the 1946 revival of Showboat in which the top dancing role went to…Pearl Primus.

In her last decade, Tamiris teamed up with her husband, Daniel Nagrin, to direct the Tamiris-Nagrin Dance Company. During that period she choreographed Memoir, about her Jewish roots; and Women’s Song, about women’s roles in society and the devastation of the Holocaust. You can find out more about Tamiris in the Jewish Women’s Archives here.

The Dance Magazine Awards honor these four dancestors who continue to inspire us.

Historical Essays Leave a comment

Leave a Reply