The pandemic has been good for dance books. Many are being published, and we’ve had more time to read them. I tend to gravitate toward stories by or about dancers (as opposed to how-to manuals, technique methodology, or theoretical treatises), so this list is obviously subjective. By chance, this year unleashed a profusion of memoirs about Balanchine and New York City Ballet. This ever-present magnet in our field is counter-balanced by stories about major Black ballet dancers.

Note that Florida University Press, which happens to have five (!) books on this list, offers a holiday discount code of XM21.

To my list of notables, I’ve added three more categories: Books Received or Announced, New Editions of Existing Books, and Children’s Books.

— + —

Notable Books:

Dancing Past the Light: The Life of Tanaquil LeClercq

By Orel Protopopescu

University Press of Florida

She was beautiful, smart, witty, dedicated, and one of the best ballerinas of her time. She was a muse and wife to Balanchine while also being cherished by Jerome Robbins. And then tragedy: At just 28 years old, she was struck down by polio and never walked again. But here’s what is equally awesome as her talent: She lived past that moment with style and resilience.

Writer and poet Orel Protopopescu tells this story in a way that allows you to feel “Tanny’s” stellar qualities, as both a dancer and a person, from the age of 11. She had studied with Mikhail Mordkin and, on advice from Balanchine, also went to the Katherine Dunham School (directed by Syvilla Fort). Along with Black dancer Betty Nichols, she performed with Merce Cunningham’s when they happened to be gallivanting in Paris at the same time. Beguiled by her dreamlike style, Balanchine made La Valse on her and Jerome Robbins made Afternoon of a Faun on her. And there were many more roles. She delivered them all with aplomb, or with sass, with melancholia—whatever was needed. She did get nervous before performances; whenever she had to dance Swan Lake, she would throw up.

LeClercq was as mystified as anyone at Balanchine’s inventiveness. Living with him at home and dancing in the studio with him, she saw his choreography pour forth with no apparent planning except listening to the music.

In 1956, on their way to a European tour while the polio epidemic still raged, all the City Ballet dancers lined up to get their polio vaccine. Tanny grew impatient and ditched the line. That tour turned out to be particularly exhausting. In Copenhagen, she came down with polio and had to be put in an iron lung. Balanchine—and the whole company— was devastated. He stopped choreographing for a year, devoting himself to her care. With great optimism, he devised exercises to stretch and activate her lifeless legs. His remedies never worked, but they gave him material for his groundbreaking 1957 ballet Agon.

Her letters to friends before, during, and after treatment reveal a quicksilver mind and playful intellect. She joked about the silver lining of her catastrophe: She never had to dance Swan Lake again.

When Balanchine’s obsession with Suzanne Farrell became painfully, publicly clear, LeClercq broke off their marriage. That was a rocky time. But she eventually regained her equanimity—and her witty self. Finding new outlets for her creativity in the 1960s, she produced two books: Mourka: The Autobiography of a Cat, filled with her own photographs; and The Ballet Cook Book, a collection of recipes from many other dancers. She later spent eight years teaching at Dance Theatre of Harlem, valiantly directing from her wheelchair.

Balanchine and Le Clercq remained devoted to each other till the end. In his will, he left her more ballets than anyone else.

Dance Theatre of Harlem: A History, a Celebration, a Movement

Dance Theatre of Harlem: A History, a Celebration, a Movement

By Judy Tyrus and Paul Novosel

Kensington Publishing Corp, Dafina Imprint

The glory of DTH, as told by former company dancer Judy Tyrus and archivist Paul Novosel, stretches over 304 pages and more than fifty years. This book illuminates the mission of Arthur Mitchell and Karel Shook to prove that Blacks could master ballet—and to bring beauty to theaters all over the world. A bounty of luscious photographs celebrates the technical, dramatic, and artistic abilities of the dancers up and down the decades. From Arthur Mitchell’s days as a star of New York City Ballet to opening a school in Harlem, to DTH’s rise on the world’s stages, to the revolutionary decision to dress the dancers in flesh-toned tights and pointe shoes, to premieres that stretch the repertoire and the dancers’ abilities, we get the inside story. Punctuating this saga are lists of what was happening in Black cultural life at the time.

This book includes a welcome section on DTH co-founder Karel Shook, who had danced with the Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo and taught at Katherine Dunham’s school. Shook was the first person who saw a future for Mitchell as a ballet dancer.

We get photographic glimpses of dancers Stephanie Dabney, Lorraine Graves, Virginia Johnson, Andrea Long, Alicia Graf Mack, Ashley Murphy, Laveen Naidu, Carolene Rocher, Eddie Shellman, Ingrid Silva, Ramon Thielen, Donald Williams; choreography by John Butler, Glen Tetley, Geoffrey Holder, Valerie Bettis and John Taras; and luminaries like Josephine Baker, Lena Horne, Marian Anderson, and of course, Mitchell s good friend, Cicely Tyson.

DTH has been called “a miracle,” and this book reveals the elements that made up that continuing-but-changing miracle. It includes the 2004–2012 hiatus due to financial issues, and the changing of the guards with Mitchell’s successor: the former DTH ballerina Virginia Johnson.

Although I wish there were an index, this book is a gift for ballet lovers, and is essential to understanding the ongoing issue of Blacks in ballet.

Onstage With Martha Graham

Onstage With Martha Graham

By Stuart Hodes

University Press of Florida

This high-spirited memoir was so much fun—and so essential to our understanding of Martha Graham— that I couldn’t resist writing about it when it came out in April. See 13 “Gems from Stuart Hodes’ New Book on Martha Graham.”

Dancing with the Revolution: Power, Politics, and Privilege in Cuba

By Elizabeth B. Schwall

University of North Carolina Press

Alicia Alonso reigned as the queen of ballet in Cuba for decades, and Elizabeth Schwall helps us understand how that happened. The ballerina had been a star with (American) Ballet Theatre, and her husband Fernando, who had danced with Mikhail Mordkin as well as with Ballet Theatre, oversaw ballet training throughout the island of Cuba. Together they created Ballet Alicia Alonso, which became Ballet Nacional de Cuba when Fidel Castro took power in 1959. Fernando’s brother Alberto set up his own company in opposition.

But Cuban dance is more than just the Alonsos. Troupes like Ballet Teatro de la Habana and Danza Abierta and their relationship to political actions are also discussed.

Schwall doesn’t shy away from contradictions. While ballet in Cuba is an art form of the people—famously, the cab drivers know who’s starring in Swan Lake on any given night—dancers of darker hues are not welcomed into ballet. While Castro’s position was anti-racist, the white supremacy of ballet was as ingrained in Cuba as it was in Europe and the U. S. So, as Schwall points out, ballet in Cuba fostered elitism and populism simultaneously. Modern dance there is more racially diverse. But the folkloric companies, mainly black, face racism from white choreographers. Also, the male dancers were expected to be hyper-masculine. All these complexities fuel an ongoing debate about which form fulfills the revolutionary ideal best.

Schwall argues that, whatever the government edicts at the time, dance artists themselves have created the multi-faceted field in Cuba, that dance itself has the power to transgress.

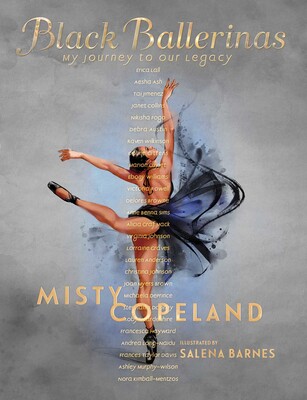

Black Ballerinas: My Journey to Our Legacy

Black Ballerinas: My Journey to Our Legacy

By Misty Copeland

Aladdin Books, Simon & Schuster

Although this book is aimed at ages 10 and up, it would be inspiring for any dancer. Each of the twenty-seven women named on the cover have blazed a path as a Black dancer in a white form. Copeland gives each one of them a full page of love and respect. The names are alphabetical, but it’s fitting that the list starts with Lauren Anderson, whose image on the cover of Dance Magazine in 1999 gave the young Misty Copeland hope. As Copeland writes in the introduction, this is not a comprehensive list, but a group of ballerinas she has felt a personal connection to. Also in the introduction she brings up the issue of colorism, admitting her own privilege in being bi-racial and light-skinned.

When she writes about her fellow luminaries—Aesha Ash, Virginia Johnson, Ebony Williams, Andrea Long-Naidu, Ashley Murphy-Wilson, Alicia Graf Mack, Tai Jimenez, and many more—she waxes eloquent about their unique qualities and the obstacles they overcame. A special place is reserved for Raven Wilkinson, who broke the color barrier back in the 1940s and, decades later, mentored Misty. The younger dancer’s connection to Wilkinson, both personal and historical, provides one of the most powerful moments: “Raven is my angel, and her wings help me take flight every day and on every stage.”

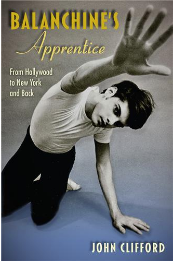

Balanchine’s Apprentice: From Hollywood to New York and Back

Balanchine’s Apprentice: From Hollywood to New York and Back

By John Clifford

University Press of Florida

This book starts off with sheer exuberance, deepens as it goes, and on the last page, articulates a beautiful devotion. John Clifford, a dancer with a rambunctious flair, reveals a whole other funnier, raunchier side of his mentor than is usually presented. Balanchine, who seemed bemused by this impulsive, extroverted, Hollywood kid, took him under his wing at New York City Ballet. In this memoir, Clifford is plenty plucky about his own abilities, but he’s even more colorful when writing about other dancers. He reports that he’s fast at picking up steps, and Balanchine liked that, but Suzanne Farrell is even faster. Apparently she could replicate the tiniest detail and inflection. “It was uncanny how she could do that,” he writes, “as if they shared the same brain.”

Clifford, who was a member of NYCB from 1966 to 1974, soaked up everything he could as a dancer and choreographer. He ultimately made eight ballets for City Ballet, and about twenty for other companies. In 1974, with Mr. B’s blessing, he left City Ballet to start the Los Angeles Ballet. His company, very active but often in financial peril, lasted for ten years. But Clifford keeps the focus here on Balanchine.

During Clifford’s spirited account of his apprenticeship, we get vivid descriptions of Anton Dolin, Maya Plisetskaya, Allegra Kent, Edward Villella, Peter Martins, Merrill Ashley, and Gelsey Kirkland (No, Mr. B did not give her amphetamines.) He tells us what Balanchine meant when he said “Don’t put your heels down,” and why the master approved of Clifford’s impulse to “entertain.” Clifford’s devotion to Balanchine is boundless, and the ways that Balanchine treats him like a son are quite moving.

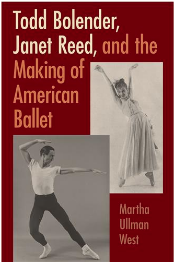

Todd Bolender, Janet Reed, and the Making of American Ballet

Todd Bolender, Janet Reed, and the Making of American Ballet

By Martha Ullman West

University Press of Florida

This double biography focuses on two feisty dancers who helped build ballet in America: Todd Bolender, who danced and choreographed for many companies, and Janet Reed, who preceded Maria Tallchief as the darling of New York City Ballet. By all accounts they were both irresistible and very funny — onstage and off—and had a delicious camaraderie. Close friends for fifty-eight years, the two were also close with legendary figures like Jerome Robbins, Tanaquil Le Clercq, and Melissa Hayden.

Based on massive research, Martha Ullman West chronicles the endless rehearsals and freelance stints. She delves into the making of iconic ballets like Robbins’ Fancy Free and Balanchine’s Agon. But she also gives accounts of lesser known ballets like Balanchine’s Renard and Bolender’s Mandarin and Still Point.

Bolender choreographed for Katherine Dunham, Jerome Robbins’ Ballets USA, the Joffrey Ballet, and countless other groups, often while dancing for either Balanchine or Robbins. His choreography, influenced by Austrucktanz leader Mary Wigman, spanned modern dance and ballet, and American and European ballet. His last long-term position was artistic director of Kansas City Ballet from 1981 to 1995.

A strong coach as well as performer—Doris Hering described her as having a sense of “the serious salted with the ridiculous”—Reed helped seed dance companies in other cities including Seattle, Portland, and San Francisco. Lincoln Kirstein felt that Reed was so lively that she attracted better known dancers like Nora Kaye and Diana Adams to NYC Ballet, where she served as ballet master in the 1960s.

The surprising moments include Bolender being almost knocked unconscious onstage by a super energized 17-year-old named Jacques d’Amboise, and Bolender’s admission that he never understood Balanchine’s counting system. Pleasant revelations include that Balanchine’s process was more collaborative than is usually described. An unpleasant one was that Lincoln Kirstein, whose dream of NYCB made it happen, habitually denigrated female choreographers.

Gratitude to Martha Ullman West for showing that dance artists who are not superstars have contributed mightily to the forging of ballet in America.

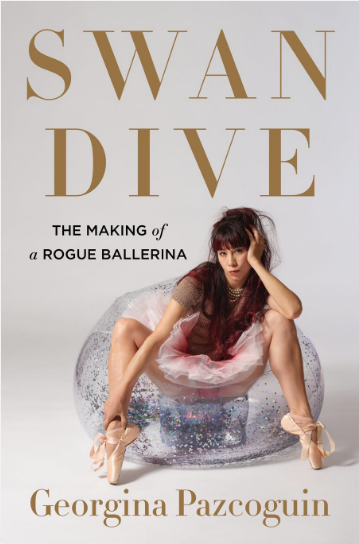

Swan Dive: The Making of a Rogue Ballerina

Swan Dive: The Making of a Rogue Ballerina

By Georgina Pazcoguin

Henry Holt and Company

Georgina Pazcoguin’s transformation from an introverted trainee to a fearlessly frank soloist at New York City Ballet makes this book a page-turner. With a swag you can’t miss, she describes her passion for dance, her chutzpah in confrontational talks, and her defiance of what she calls “ballet toxicity.” She’s shocked by her first “fat talk” when her boss, Peter Martins, tells her that her thighs are too heavy—oh, and he also questions her commitment because she asked for a day off to attend her brother’s wedding.

She never gets to play the Swan Queen, or even Sugar Plum, but she does get plum roles on Broadway in On the Town and Cats. She also starred in iconic Broadway numbers with American Dance Machine of the 21st Century: She performed a nude duet from Oh! Calcutta! by Margo Sappington and worked with Chita Rivera on the Jack Cole number “Beale Street Blues.”

Pazcoguin weighs the differences between Broadway and ballet: For musicals, you have to audition for every role, whereas a ballet company gives you security. But in a company you are dependent on one boss who can play games and be abusive. NYCB has changed leadership since Martins stepped down under a cloud of allegations, and Pazcoguin expresses hope that the NYCB dancers will now be treated with respect.

The most hilarious moment was the time in Nutcracker when the toy soldier doll didn’t show up, and Robbie La Fosse as Drosselmeyer had to improvise up a storm. Her description of his spontaneous eruption is so full of life that you feel like you are there, with the dancers backstage, gobsmacked by La Fosse’s brilliant improvisation that saves the day.

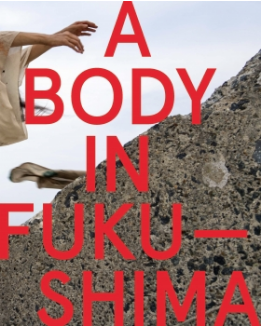

A Body in Fukushima

A Body in Fukushima

By Eiko Otake and William Johnston

Wesleyan University Press

This beautiful/tragic book moved me so much that I wrote about it here when it first came out.

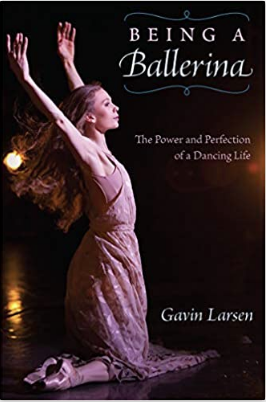

Being a Ballerina: The Power and Perfection of a Dancing Life

By Gavin Larsen

University Press of Florida

For readers who are curious about the training and the day-to-day life of a ballet dancer, this book has a lovely lilt to it. Gavin Larsen, who trained at the School of American Ballet, spent seven years at Pacific Northwest Ballet before she found a harmonious home at Oregon Ballet Theatre. From the beginning of her training to her farewell performance, she describes her experiences with sensitivity and profuse detail.

Her range of emotions is wide. Slogging through a single Nutcracker season, she hits a low as a “crumpled mess of tears in my dressing room.” Then later, in the Sugar Plum pas de deux, “suddenly at the height of the lift and on that one magnificent note, everything was crystal clear: this is the apex of life. This is the happiest a person on earth can be. This is perfection.” (The pairing of ballet with “perfection” has become so automatic that I confess I almost lopped off that part of the quote.)

The chapter on “Tumey” is bracingly real. Antonia Tumkovsky, who taught at SAB for decades, deploys the old-school style of correction by humiliation. Like all of the chapters on training, Larsen refers to herself in the third person, but it’s clearly she who falls into disfavor. For one moment, she loses her concentration, sending Mme Tumkovsky into a fury. The girl is now “the One Who Had Lapsed,” and Tumey continues tormenting her until the end of class. But how the Lapser keeps her cool is impressive. And maybe Tumkovsky is not just being petulant but is testing to see if Larsen can match her fury with her own. Larsen rises to the occasion.

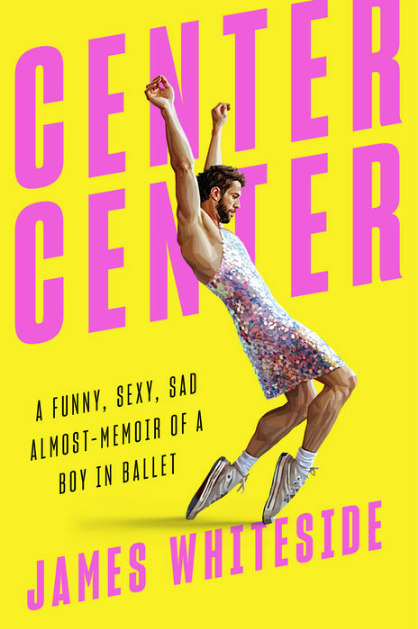

Center Center: A Funny, Sexy, Sad Almost-memoir of a Boy in Ballet

Center Center: A Funny, Sexy, Sad Almost-memoir of a Boy in Ballet

By James Whiteside

Viking

This funny, sexy, sad almost-memoir starts with James Whiteside’s mother, a strong woman who let little James be whoever he wanted to be. Family, friends and hard work are what this story is all about. Whiteside becomes painfully torn when he’s about to go onstage as the Prince in The Sleeping Beauty and he’s just received a text saying his mother is dying. He describes his unbearably conflicting emotions poignantly and powerfully.

The exhilaration of dressing in drag and other antics with friends are liberating. Meanwhile Whiteside struggles to attain the perfect boy ballet body, and his goal is to get past that obsession to work on his technique. But don’t expect any details about his ten years with Boston Ballet or his nine years with American Ballet Theatre. Center Center is mainly about claiming the right to flamboyance and feeling centered in your chosen way to express yourself.

Dance Spreads Its Wings: Israeli Concert Dance 1920–2010

Dance Spreads Its Wings: Israeli Concert Dance 1920–2010

By Ruth Eshel

DeGruyter

Batsheva Dance Company is the tip of the iceberg in this dance-rich country. Former dancer/choreographer and critic Ruth Eshel unfolds a wealth of dance going back to before Israel was even a country. She follows pioneers like Gertrud Kraus, who fled Austria at the peak of her dance career and started Israel Ballet Theatre; Sara Levi-Tanai and her sublime muse, Margalit Oved, of Inbal Dance Theater; Bethsabée de Rothschild, who started both Batsheva and Bat-dor Companies; and Tamra-Ramla Dance Theater (co-founded by Zvi Gotheiner). Eshel ties each new wave of creativity to political developments. Americans who came to nurture the Israeli dance scene included Jerome Robbins, Anna Sokolow, Talley Beatty, and later Lisa Nelson and Simone Forti. Chapter headings like “Israeli Expressionist Dance Meets American Dance” and “To Dance in Holy Jerusalem and Socialist Haifa” reflect investigations into ongoing questions.

Eshel highlights independent choreographers like Yasmeen Godder, Arkadi Zaides, Roy Assaf, Hillel Kogan, and Sharon Eyal. It’s illuminating to read about the evolution of major companies like Rami Be’er and the Kibbutz Contemporary Dance Company, Inbal Pinto and Avshalom Pollak, and Noa Wertheim and Adi Sha’al of Vertigo. And of course, Ohad Naharin and Batsheva Dance Company. Eshel also touches on community efforts to bring Arabs and Israelis together in Haifa and the international dance festivals in Ramallah. She herself met the influx of Ethiopian Jews with dance workshops and helped them develop their choreographic voices based on their folk dances. Whether you read this 500-page volume from start to finish or keep it on your shelf for reference, you are sure to get a sense of the global dance activity in Israel over the years.

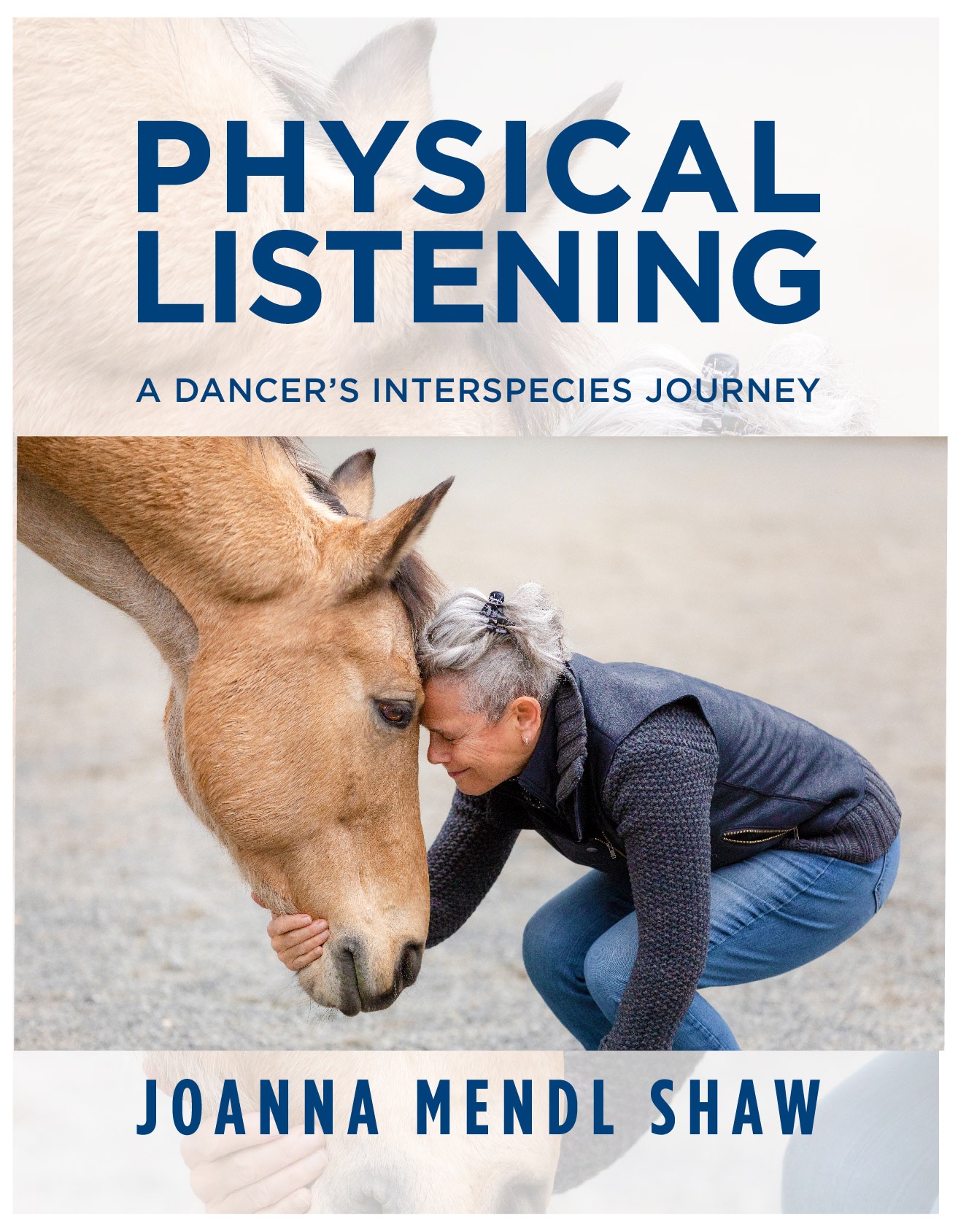

Physical Listening: A Dancer’s Interspecies Journey

Physical Listening: A Dancer’s Interspecies Journey

By JoAnna Mendl Shaw

Arnica Press

As educators, we know that listening is crucial, and that listening leads to imagining. JoAnna Mendl Shaw has extended and developed these intuitive knowings into her multi-faceted practice of physical listening.

A child of Jewish refugees, Mendl Shaw learned to ski at 3 years old. It was exhilarating, and she excelled. “The mountain,” she writes, “was where my physical intelligence flourished.” Although she wasn’t immediately thrilled by dance classes, she grew to love them.

The book gives a detailed account of her life’s work as a dancer, educator, Laban Movement Analyst, and mastermind of mixing species in performance. With great lucidity, she explains how each phase led to the next in her creative life. Thus we hear about the doodle game she played with her father, her resolve to make dances that leave a visual tracing, and origami folding for Zoom workshops.

An invitation from Mount Holyoke College to make a site-specific piece unleashed Mendl Shaw’s equestrian imagination. She started working with horses and never looked back. Although, in these performances each horse is controlled by a professional rider, the dancers concentrate on a dialogue, “giving and taking leadership” with the horses. In one episode, a horse nestles close to a dancer’s shoulder, and Mendl Shaw imagines the animal is whispering to the dancer.

Within each chapter are sections on practical thinking, poetic sensing, and scores. The scores—for example, an obstacle course, a blind learning score, a folding score, walking score, touch and weight sensing—are a valuable resource for anyone teaching dance composition or improvisation.

This book is a testament to what you can do when you break through the conventions of performing. It’s also a compendium of ways to engage in a life-art-reflection process.

— + —

Before we move on to the other categories, I want to register an objection to a trend I’m seeing. Three of the ballet books above represent the dancers with drawings instead of photographs. Maybe it’s my background in journalism, or my respect for photographers, but I feel this choice does not do the dancers justice. If I’m curious about a dancer, I want to see what kind of spirit that person brings to their dancing. I want to see the artistry created by that dancer onstage, or in the studio. So, to my eye, Center Center, Being a Ballerina, and Black Ballerinas would be more exciting if they were illustrated with photographs rather than drawings.

— + —

Books Received or Announced:

Baring Unbearable Sensualities: Hip Hop Dance, Bodies, Race, and Power

By Rosemarie A. Roberts

Wesleyan University Press

Co-director of the Cultural Traditions Program at Jacob’s Pillow, Rosemarie Roberts asks the question, “Can a body be both singular and collective at the same time?” While dipping into Katherine Dunham’s 2002 interview at the Pillow, the author also interviews dance artists Rennie Harris, Mr. Wiggles, and Moncell Durden as well as scholars like Thomas DeFrantz, Ananya Chatterjea, and Brenda Dixon Gottschild.

It Could Lead to Dancing: Mixed-Sex Dancing and Jewish Modernity

By Sonia Gollance

Stanford University Press

Even though it was forbidden for Jewish men and women to dance together in 19th-century Europe, people still danced. Sonia Gollance traces social dancing in taverns, ballrooms, weddings and dance halls and the shift in sexual mores as the waves of immigrants came to these shores. The appendix defines about forty genres of social and folk dances from bolero to Charleston to the Hora, to the Kazatsky to Mambo, the German Cotillon to polonaise, the mazurka to the merengue.

Tandem Dances: Choreographing Immersive Performance

By Julia Ritter

Oxford University Press

A scholarly treatment of immersive dance including Punchdrunk’s Sleep No More and Third Rail Project’s Then She Fell.

My West Side Story, a Memoir

By George Chakiris with Lindsay Harrison

Lyons Press

The brooding sensuality and sexy dancing of George Chakiris’ Bernardo was felt all over the world. Here the charismatic dancer/actor tells us about his career leading up to and away from his Oscar-winning swirl as Bernardo.

Love Dances: Loss and Mourning in Intercultural Collaboration

By SanSan Kwan

Oxford University Press

SanSan Kwan, a dancer/scholar at UC Berkeley, focuses on duets that bridge East and West sensibilities.

The Oxford Handbook of Contemporary Ballet

Edited by Kathrina Farrugia-Kriel and Jill Nunes Jensen

Oxford University Press

This massive collection includes essays by Kyle Bukhari on Twyla Tharp, Anna Seidel on Hans Van Manen, Ann Nugent on William Forsythe, Laura Cappelle on Jean-Christophe Maillot, Tanya Wideman-Davis on Dance Theatre of Harlem, Apollinaire Scherr on Alexei Ratmansky, Gia Kourlas on Mark Morris, and lots more—over 1,000 pages worth.

The Ballerina Mindset: How to Protect Your Mental Health While Striving for Excellence

By Megan Fairchild

Penguin Random House

From this sparkling New York City Ballet principal dancer’s Instagram page: “It’s part self-help, part autobiographical, and I’m super excited to share the nuggets of wisdom that I have learned throughout my career. One of them being: DO NOT READ YOUR REVIEWS.”

Funding Bodies: Five Decades of Dance Making at the National Endowment for the Arts

By Sarah Wilbur

Wesleyan University Press

This is a behind-the-scenes look at how the National Endowment for the Arts, established in 1965, has affected dance communities across the country.

Renegades: Digital Dance Cultures from Dubsmash to TikTok

By Trevor Boffone

Oxford University Press

This book is about the interplay of social media and hip hop. Chapter headings include “Gone Viral: Creating an Identity as a Hip Hop Artist” and “When Karen Slides Into Your DMs: Race, Language, and Dubsmash.”

The Oxford Handbook of Jewishness and Dance

Edited by Naomi M. Jackson, Rebecca Pappas, and Toni Shapiro-Phim

Oxford University Press

This anthology overflows with subjects that interest me, but it comes too late for me to give it the attention it deserves. With contributions from foremost dance scholars Naomi Jackson, Marion Kant, Hannah Schwadron, Douglas Rosenberg, Hannah Kosstrin, Rebecca Rossen, and Laure Guilbert, and dance artists Liz Lerman, Ze’eva Cohen, Victoria Marks, Hadar Ahuvia, and Jesse Zaritt, this volume broadcasts that Jewish dance scholarship is here in a big way. I look forward to diving into this book and writing something about it in the near future. (Disclosure: the book is based on a conference at Arizona State University that I participated in as a curator and learner.)

Memories of Rudolf Nureyev

By Nancy Sifton

Arnica Press

A collection that draws from more than a thousand performances of the superstar Soviet defector attended by traveler/archivist Nancy Sifton. The memories included transcriptions of many interviews.

— + —

New Editions of Existing Books:

No Fixed Points: Dance in the Twentieth Century

By Nancy Reynolds and Malcolm McCormick

Yale University Press first published in 2003, now in paperback

A thorough, masterful history of twentieth-century concert dance, this 900-page volume covers a vast stretch of American and European dance from minstrelsy and vaudeville on up through current choreographers. An invaluable resource.

Moving Through Conflict: Dance and Politics in Israel

Edited by Dina Roginsky and Henia Rottenberg

Routledge, first published 2020, now in paperback

The nine chapters include Henia Rottenberg on “artistic activism” in the works of Rami Be’er and Arkadi Zaides and Naomi Jackson’s analysis of maverick dance artist Jesse Zaritt’s work. An appendix lists many Dabke groups in Israel and in the Palestinian Authority.

This Very Moment: teaching thinking dancing

By Barbara Dilley

Originally published by Naropa University Press in 2015.

Digital edition from Contact Editions

Master teacher-founder of contemplative dance practices and past member of Merce Cunningham Dance Company, Barbara Dilley created this multi-faceted contemplation of her dance experiences. She weaves her influences— John Cage, Yvonne Rainer, Tibetan Buddhism, and the anarchism of Grand Union—into her unique approach to teaching at Naropa University. A poetic collage of observations and practices.

— + —

Children’s books:

My Story, My Dance: Robert Battle’s Journey to Alvin Ailey

By Lesa Cline-Ransome

Foreword by Robert Battle

Simon & Schuster

or through Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater

My Daddy Can Fly

By Thomas Forster with American Ballet Theatre

Penguin Random House

Grand Jeté and Me

By Allegra Kent

HarperCollins

— + —

— + — + —

Featured 7

Again my thanks for the marvelous review of my book, as well as Stuart Hodes’, and John Clifford’s. I would like to recommend as well another University Press of Florida book, K. Mitchell Snow’s A Revolution in Movement, released last year, subtitled Dancers, Painters and the Image of Modern Mexico (and forgive me if this was on last year’s list), of interest to people like me who are fascinated by the ways in which dance and visual arts so frequently intersect, as well as the far-reaching influence of the tours of Pavlova and her company and the Ballets Russes.

No, I didn’t know about that book, so thanks for telling us about it. There should be more books about the alliance between dancers and visual artists.

Thanks for this overview. I’d like to suggest “Poetry of Movement: Modern Dancers NYC 1979-80”. Check out Amanda Kreglow’s long-overdue glimpse via her outstanding photos into an era of dancers who bridged the great modern dance legacies with their efforts to declare their own artistic autonomy.

Thanks much for this suggestion.

https://www.teneues-boeken.nl/free-a-life-in-images-and-words-by-sergi-polunin-p.html

Free, A Life in Images and Words, Sergei Polunin

FREE is an intimate encounter with the enfant terrible of ballet. This beautiful book contains an extensive selection of photos from the life of Sergei Polunin on and off stage and tells his life story.

With a foreword by Dame Helen Mirren and Albert Watson.

Thanks. I didn’t know about this one.

Wendy: just took a look at this extraordinary list of current publications on dance. What a diverse and remarkable inventory! It is so heartening to see the variety and depth of the sujects of these books. Dance has truly spread its wings and delved into areas of social and political importance that would never have been discussed years ago. Thanks so much for your cogent analyses as well!