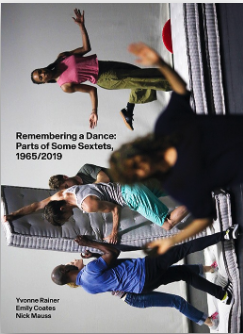

Yvonne Rainer’s epic task dance from 1965, Parts of Some Sextets, was given new life in 2019 when Emily Coates decided to reconstruct it. And now it has been given a third life as a luminous book collaboration between Rainer, Coates and designer/performer Nick Mauss. Remembering a Dance: Parts of Some Sextets, 1965/2019, was just published by Performa, Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art, and Lenz Press. It invites the reader to dive deep into Rainer’s many-layered work and the ideas that generated it—and the feelings stirred up by the reconstruction 54 years later.

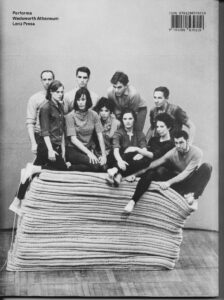

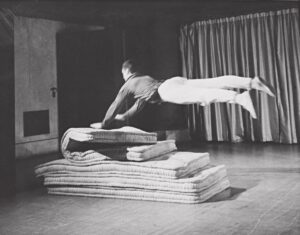

Coates, a dance artist, researcher, and Yale professor who has danced with Rainer for more than 20 years, got the idea that Parts of Some Sextets was “the missing piece in the puzzle of Yvonne’s thinking.” She flew to the Getty Research Institute in Los Angeles, where Rainer’s archives are stashed. Coates’s journey of searching, finding, not finding, emailing with Rainer, is the (re)birthing story of the second iteration of what Rainer calls My Mattress Monster. With some puzzles still unsolved, Rainer and Coates gathered a new, more diverse group of eleven dancers and non-dancers. Commissioned by the Performa 2019 Biennial, they performed the new version at Gelsey Kirkland Academy of Classical Ballet in DUMBO. This version was a bit longer, had only ten mattresses instead of twelve, and gave the dancers more freedom in the second half. But it kept the 31 tasks (e.g., bird run, bent-over walk, fling, rope duet, crawl through below top mattress) as much as possible. Curiously, it was more warmly received than 54 years earlier, perhaps because seeing a full-evening work by Yvonne Rainer has become a rarer event than in 1960s downtown.

Rainer and Emily Coates studying xeroxes of archival photos. Mary-Kate Sheehan at right, Baryshnikov Arts Center, 2019, Ph Simon Gérard.

The book Remembering a Dance is both an archive and an art object. It contains Rainer’s original essay about Parts of Some Sextets (PoSS), her notes and charts, detective work by Coates, five pithy essays, Jill Johnston’s summary of Rainer’s oeuvre up to 1965, archival photos, and—for a perverse kind of balance—a negative review from Jill Johnston. As an art object masterminded by Mauss; it offers gorgeous new photos mostly by Paula Court, a three-way conversation between Rainer, Coates, and Mauss; and inspired juxtapositions and overlappings of color photos with vintage photos.

Yvonne’s nature is to resist the status quo. The very title of her original essay, reprinted here in full, flouts the conventions of a title: “Some retrospective notes on a dance for 10 people and 12 mattresses called ‘Parts of Some Sextets,’ performed at the Wadsworth Atheneum, Hartford, Connecticut, and Judson Memorial Church, New York, in March, 1965.” She is-hell bent on undermining the usual virtues of grace and fluidity in dance. Just as John Cage, a big influence on her (and almost everyone in the art world at the time), rejected melody in favor of noise, she rejected flow in favor of bluntness. Cage didn’t want his pieces to be easy to listen to; she didn’t want hers to be easy to watch. She wanted changes to be “as abrupt and jagged as possible…So I resorted to two devices I have used consistently: Repetition and interruption.…both factors were to produce a ‘chunky’ continuity, repetition making the eye jump back and forth…” In case her dissenting voice was not perfectly clear, she added a brief postscript: “NO to spectacle no to virtuosity no to transformations and magic…” You know the rest. In the recent interview toward the back of the book, Yvonne explains that she never expected this list of refusals to stick. It was intended to be provisionary, “never meant to be a set of principles to live or create by.”

Rehearsal, 2019. From left: Nick Mauss, David Thomson, Shayla-Vie Jenkins, Rachel Bernsen, Emily Coates, Liz Magic Laser, Patrick Gallagher, Ph Paula Court.

The 2019 performance certainly had that “chunky” continuity. A mashup of task-with-objects, robust dance phrases, and various mattress pilings, the actions changed every 30 seconds. This haphazard-looking commotion coexisted with the sound score of Rainer’s monotonous reading of 18th-century New England minister William Bentley’s diary. In the book too, people and mattresses look randomly scattered on the page. (Rainer has said that she liked to compose dances with the look of randomness.) And yet there is form and shape: One person might be hurtling toward a mattress, another tying a knot with rope, a foreground figure too blurry to distinguish, but there’s a cogency anyway. (You may notice that the cogency of the cover image has been knocked sideways…as in, perhaps, “No to uprightness.”)

While digging into the archives at the Getty, Coates leaves no stone unturned. But she becomes “addicted” to the archive and starts reading other notes of Rainer’s, written under the influence of hallucinogenics. The words were so sensual, so much about the body, so unguardedly poetic that Coates admits to falling in love with the 30-year-old Yvonne’s trippy prose. Perhaps Coates’s wildest idea is the proposition that “we accept these reflections as another kind of theory. And why not? They are as revealing of her artistic production as her published writing.” As someone who is often frustrated by overly academic theories of dance, I second that emotion.

Rehearsal, 2019. Foreground: Shayla-Vie Jenkins, Brittany Engel-Adams, David Thomson. Background: Mary-Kate Sheehan, Liz Magic Laser, Timothy Ward, Patrick Gallagher, Emily Coates, Nick Mauss, Ph Paula Court.

The most grippingly relevant theme is broached by David Thomson in his raw and articulate essay “It Takes a Village.” A longtime Rainer dancer (and freelance dancer/choreographer), he writes unflinchingly from both the inside and the outside, refusing to ignore the racial gap. Calling Parts of Some Sextets 1965/2019 “an ephemeral memory palace,” he reacts sharply—twice—to the presence of race in Bentley’s tale of mundane life in 18th-century Massachusetts. “Hearing the word Negro in his diary reverberated within me. It named me, called me out, and threw my body back into a difficult historical frame…And yet, simultaneously, it comforted me, in knowing that a person of color was noted in the archive in a benevolent way.” In the second instance, just as Thomson was performing a gestural solo downstage right, a Black servant named Jack surfaced in the recorded narrative. Bentley was lauding Jack, a wholly honorable person who had unexpectedly died. Thomson writes, “All at once, the past and present merged. I was locked in him and history. I became a living avatar for Jack… His life became tangible, and, personally, I embraced this meeting, feeling the power and necessity of the moment. I became his ghost manifest.”

The book is full of ghosts. Looking at the black-and-white images of a time gone by, we might recognize some of the people in the original PoSS (listed below). Paula Court’s vibrant color photos bring it back to this century. Occasionally the recent photos are converted to greyscale, nicely blurring the distinction between the two eras. For a moment, 1965 and 2019 merge.

While chunky discontinuity reigns in some of Rainer’s works, there is continuity in her work over time. For example, mattresses appeared in her previous piece Room Service (1963) and her later work Carriage Discreteness (1966). Her idea of interruption can be seen in many works. Jill Johnston, in her 1965 summary of Rainer’s oeuvre, identifies “irresponsible noises” as a kind of interruption: “Barking, grunting, mumbling, stammering, wailing.” One of the interruptions in the 2019 version (when Rump was still in office) was Rainer’s recorded voice suddenly calling out terms like “F^%#ing moron!” “Shameless demagogue” or “Cynical asshole.”

Back when Yvonne Rainer was saying “No” to all those things in the postscript-turned-manifesto, what was she saying “Yes” to? In the images in Remembering a Dance, one can glean hints of Rainer’s “Yesses”: intimacy, effort, community, the unadorned physicality of functional movement, awareness of one’s environment, a challenge to the audience’s way of seeing/absorbing, and the readiness to accept change. All time-honored aspects of life and art…and yet also an invitation to look at the ordinary with fresh eyes.

* Front cover, bottom to top: David Thomson, Emily Coates, Timothy Ward, Patrick Gallagher, Liz Magic Laser, Shayla-Vie Jenkins, Ph Paula Court, 2019.

** Back cover: Back row from left: Robert Morris, Steve Paxton, Tony Holder, Robert Rauschenberg. Front row from left: Lucinda Childs, Yvonne Rainer, Deborah Hay, Sally Gross, Judith Dunn, Joseph Schlichter, Ph Peter Moore, 1965.

Featured 2

Love those yeses – intimacy and connection is what’s important now more than ever.

Enjoyed this so much. Now to find the book.