In 2018, Brooklyn Academy of Music celebrated 35 years of its interdisciplinary Next Wave Festival with a lavish book. The festival had become so essential to New York art-going that it helped revitalize downtown Brooklyn. I was commissioned to write the essay on dance. I had performed at BAM in 1976 with Trisha Brown, and I had seen most of the dance works in the festival for those decades. To prepare for writing this, I made frequent trips to the BAM Hamm archives on Dean Street in Brooklyn to watch videotapes of works I had not seen as well as those I had seen long ago. This immersion reminded me how much I loved, really loved, so many of these works. Since the book, BAM Next Wave Festival, is not easily available, I decided to repost this essay here, with thanks to editors Steven Serafin and Susan Yung, Archivist Sharon Lehner, Archives Manager Louie Fleck, and all the photographers. Reprinted with permission from BAM and Print Matters Production.

In 2018, Brooklyn Academy of Music celebrated 35 years of its interdisciplinary Next Wave Festival with a lavish book. The festival had become so essential to New York art-going that it helped revitalize downtown Brooklyn. I was commissioned to write the essay on dance. I had performed at BAM in 1976 with Trisha Brown, and I had seen most of the dance works in the festival for those decades. To prepare for writing this, I made frequent trips to the BAM Hamm archives on Dean Street in Brooklyn to watch videotapes of works I had not seen as well as those I had seen long ago. This immersion reminded me how much I loved, really loved, so many of these works. Since the book, BAM Next Wave Festival, is not easily available, I decided to repost this essay here, with thanks to editors Steven Serafin and Susan Yung, Archivist Sharon Lehner, Archives Manager Louie Fleck, and all the photographers. Reprinted with permission from BAM and Print Matters Production.

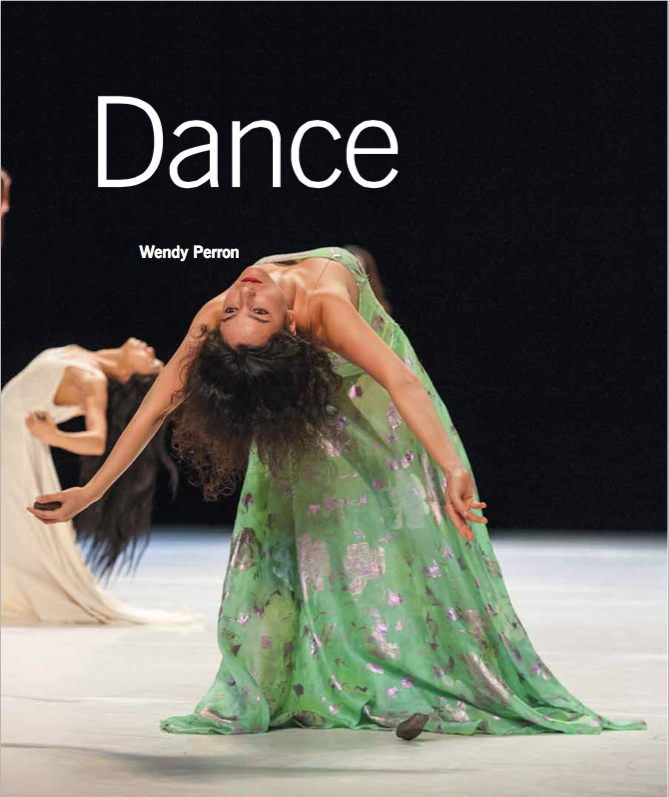

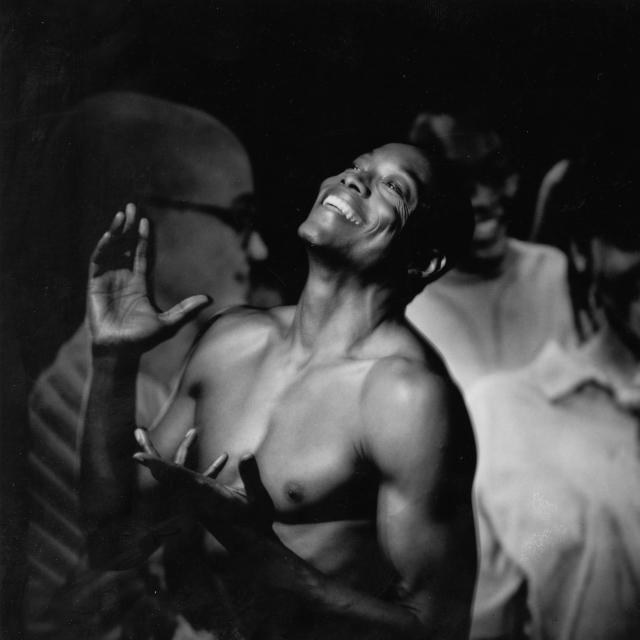

Original frontispiece of my chapter on dance, showing Morena Nascimento in Pina Bausch’s “Como el musguito, en la piedra, ay si si si …,”, Ph Stephanie Berger.

If you have followed any part of the Next Wave Festival over the course of its 35 years, you’ve witnessed some of the great minds of modern dance: Merce Cunningham, Trisha Brown, Bill T. Jones, Mark Morris, Pina Bausch, William Forsythe, and Ohad Naharin. These artists and many others have been nurtured and developed by legendary BAM impresario Harvey Lichtenstein and his chosen successor, executive producer Joseph V. Melillo. We have watched each of them grow and change. We have been close enough to be swept away by their beauty or staggered by their audacity. They have engaged us in the issues of our time: race, gender, the environment, the relation of art to life. Whether their aesthetic places them in the category of minimalism, tanztheater, epic narrative, or dances of cultural identity, they have all alighted in one spot: BAM. Although many new dance presenters have sprouted up in the last 35 years, the Next Wave continues to be a beacon of forward-looking dance.

These dances do the traditional work of art. They educate, edify, and entertain, but they also unleash. They unleash the individual imagination, experimental ideas, collaborative alchemy, and altered states in both performers and viewers. Some notably memorable moments: Molissa Fenley charging across the Lepercq Space, sculpting the air with her arms to the jazz music of Anthony Davis in Hemispheres (1983); or Bill T. Jones as a wobbly pre-verbal “fabricated” man in Secret Pastures (1984); or Tanztheater Wuppertal’s Julie Shanahan yelling to her two suitors to throw tomatoes at her in Palermo Palermo (1991). You might have seen Dana Caspersen enacting a ferocious split personality, her seething body animated by the exaggerated voices of two opposite characters in William Forsythe’s I don’t believe in outer space (2011).

Not only has the Next Wave cultivated these individual artists over decades, it has also cultivated audiences. The festival has accustomed us to the unaccustomed, the unconventional, and the unpredictable. It has raised the standards for interdisciplinary work and it has raised our curiosity for dance around the globe. It’s given a home for experimental work that may or may not eventually expand into a proscenium space.

But before there was a Next Wave Festival, there was a Next Wave Series. Initiated as a pilot project by Harvey Lichtenstein for two seasons, in 1981 and 1982‒83, the series gave experimental American artists an opportunity to play for a broader audience. Dance was in the forefront of the Next Wave from the beginning, guided by Lichtenstein, who had danced professionally with modern dance greats Pearl Lang and Sophie Maslow. Innovators Trisha Brown, Laura Dean (with a young Mark Morris in her company), and Lucinda Childs were all featured in the Next Wave Series as well as Bill T. Jones and Arnie Zane. The overwhelming success of the series enabled Lichtenstein to expand into an annual festival.

Interdisciplinary collaborations that came to define the Next Wave were encouraged from the start, illustrated by two productions that served as artistic landmarks in American dance: Trisha Brown’s Set and Reset, performed in the inaugural season, an acknowledged masterpiece by a mature artist; and Secret Pastures from the second season, a provocative work by emerging young mavericks Bill T. Jones and Arnie Zane. Both pieces utilized rigorous postmodern methods of problem-solving to mount a fully elaborated creative vision. Both were distinctly American, yet the two visions were almost opposites of each other.

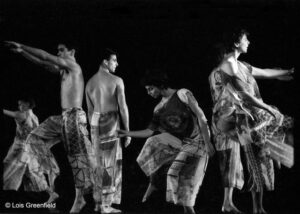

Set and Reset 1983 From left: Diane Madden, Randy Warshaw, Stephen Petronio, Vicky Shick, Eva Karczag. Ph Lois Greenfield

Trisha Brown, along with visual artist Robert Rauschenberg and composer Laurie Anderson, crafted an exhilarating mind-body synergy in Set and Reset. The piece seemed to levitate, fueled by the illusion of spontaneity: the sense of flying high, a connection to air, decision-making on the spot, was palpable. More than any other previous work, Set and Reset showed how a collaboration of basically formal approaches could blossom into a fully blown opus. Anderson’s music, with a tango-like beat, propelled the dance in many directions, mostly away from center stage. And Rauschenberg’s set, which started as a light-filled sculptural form on the floor and then rose upward, lent a sense of liftoff. Adding to that was the riddle of the transparent wings: When the dancers were visible behind those wings, were they still performing?

For the performers, momentum of body coincided with momentum of mind. In making the dance, they had treated specific dance phrases with suggestions like “Play with being visible and invisible.” For the audience, you had to sit on the edge of your seat to catch even a fraction of the interaction. When dancer Diane Madden curves over with an arm extended outward, Trisha Brown rushes in from stage left, grabs her arm and flings her across the space—to land in the arms of Stephen Petronio, who has appeared out of nowhere. Split-second timing is the name of the game. The six ready-for-anything dancers are all aiding and abetting each other’s recklessness. Another time, Petronio―who would soon found his own company―slowly leans on one dancer and when he’s just about to fall, a different dancer is suddenly visible underneath him. Conceal and reveal, deflect and proceed. For all of minimalism’s supposed disregard for the audience, Brown captures the audience’s attention with near crashes, clever escapes, and playful dares, all embedded in her dreamy fluidity and Anderson’s syncopated score.

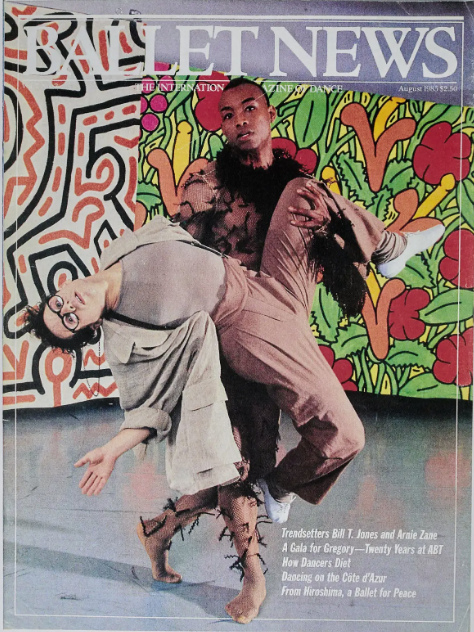

If Set and Reset leaned toward abstraction, Secret Pastures hinted at narrative. They were the two halves of the new collaborative postmodernism. In Secret Pastures, for which Keith Haring designed sets, Willi Smith designed costumes, and Peter Gordon’s Love of Life Orchestra made the gorgeously quirky music, each element lent its own fabulousness. Gordon once commented that he as well as Jones and Zane all had “a desire for sensual answers to formal questions.” Arnie Zane as “The Professor” sported a lab coat, glasses, and a Mohawk haircut. Janet Lilly sauntered in a fur coat made of white Afro wigs sewn together, and Seán Curran skipped and skittered in blue hair. As “The Fabricated Man,” Jones was curious, innocent, open to learning but also vulnerable. He moved like an underwater animal, wandering and wondering despite the added lumps to his costume. Anna Kisselgoff described him in the New York Times as fusing “a pantherine grace with a massive power.”

Beatriz Schiller’s photo of Arnie Zane and Bill T. Jones in Secret Pastures, with Keith Haring designs, appeared on the cover of Ballet News.

The most moving scene was where the Professor tries to teach the Fabricated Man how to behave. The magnetism between Zane, with his near-pantomimic sharpness, and Jones, in his feigned awkwardness was poignant. The Professor circles the Fabricated Man, who accidentally lurches at the Professor. Although the characters were cartoonish, the process consisted of solving tasks—at a wondrous level of virtuosity. Perpetually buoyant, Curran―whose own company would later perform in the Next Wave―nimbly performed an Irish jig overlaid with a series of Jones’s arm gestures while also inserting ballet beats.

The giddy Secret Pastures astonished some, provoked others. Esteemed critic Deborah Jowitt wrote that it “may be the first dance work of any consequence to acknowledge the influence of MTV on our perception.” Some critics felt the characterizations were more style than substance. Others appreciated the mashing up of aesthetics. As Kisselgoff noted in her New York Times review, Marcel Fieve’s extreme haircuts and colors helped make the dancers look witty and chic. She felt the sensibility was “punk art domesticated, a collaboration between received intellectual influences from academe and a fashion consciousness that keeps an eye on the street.” For the Jones/Zane company, Secret Pastures marked a pivotal moment. With its connections to the art and fashion worlds, it attracted celebrities like Andy Warhol and Madonna to BAM. Word spread, leading to a surge of international touring. In effect, Secret Pastures put the Bill T. Jones/Arnie Zane Dance Company on the map.

Brooklyn: Portal to Europe

The 1980s were the height of postmodern “abstract” dance in New York. Influenced by innovative choreographers like Merce Cunningham, Trisha Brown, and Lucinda Childs, American “dancemakers” were making dances about form and motion, pattern and space. At the same time, dancemakers in Europe were investigating narrative with a modernist sensibility. The Next Wave Festival was only two years old in 1985 when the Europeans started coming, beginning with German choreographer Pina Bausch and Tanztheater Wuppertal and Anne Teresa De Keersmaeker’s Brussels-based group Rosas.

Bausch’s work was a revelation for American audiences. And the regularity of Tanztheater Wuppertal’s appearance at BAM—nearly every other year—made it an ongoing and evolving revelation. Elegance was juxtaposed with absurdity, cruelty with lavish dancing. Gender was a polarizing force; extreme stereotypes were exhibited, questioned, and mocked. Bausch excavated fantasies both dreamy and nightmarish. Flirtation devolved into abuse. A woman scrubs the floor from one side of the stage to the other while a man keeps tossing popcorn onto the floor. This kind of scene leads to questions. Are the women enjoying their abuse? Is attracting the opposite sex the main goal?

Two Cigarettes in the Dark, Tanztheater Wuppertal Pina Bausch, 1994. Ph Dan Rest

While American postmodernists like Trisha Brown and Lucinda Childs favored a “neutral” facial expression, Bausch’s dancers were drenched in irony, making commentary on performance itself. They adopted a performance mask, be it sardonic, sweet, desperate, impassive, or unhinged. While Brown and Childs had an aversion to flamboyance, Bausch wrapped her women in extravagant gowns of luscious colors. The monumental set designs were possibly the prototype for the unwritten edict to “fill the stage” in Next Wave interdisciplinary collaborations. Rolf Borzik had created set and costume designs until his death in 1980; subsequently, Peter Pabst designed sets and Marion Cito the costumes. Bausch made her BAM debut in 1984 showcasing four works, and in the following year was invited to the festival for a three-week engagement. Audiences were hooked—and not just dance audiences. Her productions attracted people of all persuasions and were often sold out. Tanztheater performers were our hostesses: smiling, unctuous, hiding naughty secrets up their sleeves. The contrast between their elegant demeanor and the absurd, sometime cruel things they did to each other was mesmerizing.

Tanztheater Wuppertal’s first Next Wave Festival program—comprising Arien, Kontakthof, Gebirge, The Seven Deadly Sins, and Don’t Be Afraid—was unsettling. At the time, the women’s movement had challenged gender stereotypes, but Bausch clung to exaggerated gender roles: Men were drawn to women like catnip, and the women happily tried to please the men. Both genders poked, squeezed, and wrenched each other’s body parts as an accepted ritual. In one diagonal procession, the women jammed their feet into high heels as a necessary torture. Some of us went to see Tanztheater Wuppertal with a combination of dread and fascination.

But one cannot deny the sheer scale of Bausch’s thinking. For Palermo Palermo, the first thing that happened was a huge brick wall (set design by Peter Pabst) keeled over backward, scattering debris all over the stage. In Der Fensterputzer (1997), we encounter a red-glowing mountain of 40,000 silk flowers, also designed by Pabst, which the dancers dive into, burrow under, or slide down.

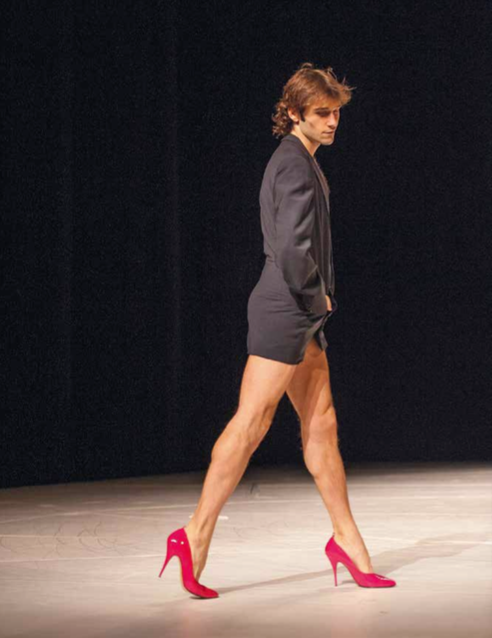

Although most of her scenes assumed an automatic heterosexuality, she expanded to other kinds of gender play. Male dancer Jan Minarik in Palermo Palermo strutted wearing a crown of cigarettes, bare legs, and red high heels; in contrast, Nazareth Panadero—his female counterpart—used her mannish voice to command our attention. All Bausch dancers are keenly aware of performing. Whether they are engaging in degrading or uplifting actions, they are about performing.

By the time of Two Cigarettes in the Dark (1994), the balance of brutal to benign began to tip toward the latter. It became clear that Bausch’s overall theme was the absurdity of life in general rather than specifically about sexual attraction. A woman with a pot tied to her runs and smashes against a wall over and over, while a man tries to intercept her. A man wielding an ax roams ominously while a woman serenely practices yoga. Bausch’s work offers the best examples of theatrical Dada in our time, with radical juxtapositions that require a double take. We get some comic relief in the person of Dominique Mercy, who periodically scampers onto the stage as a chef/conductor, setting up a cooking table on which nothing gets made. He cavorts so recklessly that his head seems about to fling itself away from his body. Later, in a previously hidden alcove, he takes a bath—wearing flippers.

Whether her scenic collaborator was Rolf Borzik or Peter Pabst, each one of Bausch’s works immersed us in a whole different world. While Americans were going minimal, she was going maximal. Gesamstwork—the totality of parts—wins us over. In Bamboo Blues (2008), we are intoxicated by a world of the senses. Swatches of cloth billow; towels wrap around torsos like saris. Combativeness is gone. The elegant Shantala Shivalingappa offers segments of a long ribbon to the audience, asking sweetly, “Can you smell it? It’s cardamom.” Created during a residency in South India, Bamboo Blues nevertheless has little to do with the reality of a particular region. Hunger, poverty, stench, fires, street children—none of these things make their way into this piece. Bamboo Blues is all about pleasure. As Bausch has said in interviews, the real world became so full of violence that she felt compelled to create pleasure onstage, a transition notable in her later works.

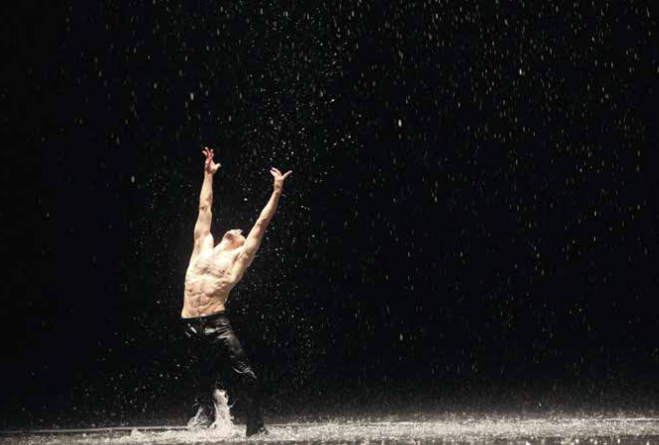

Rainer Behr in Vollmond, Tanztheater Wuppertal Pina Bausch, 2010. Ph Julieta Cervantes

The theme of water, seen previously in Arien and other works, reaches its peak in Vollmond (2010). It’s as though all the glasses, buckets, and puddles of water in previous pieces poured into this great river of water on the Opera House stage. To see Rainer Behr splashing through the water, his arms and legs whipping outward, is to see a man’s soul lashing out. Then, in her final work, “…como el musguito en la piedra, ay si, si, si…” (Like moss on a stone), which came to BAM in 2012, three years after Bausch’s death, we see their pleasure in a preverbal, polymorphous way. Sixteen dancers are sitting on the floor in a diagonal, alternating male and female. They are each massaging the head of the person in front of them. They are connected through touch, through care, and through the ability to take and give pleasure at once.

Pablo Aran Gimeno in “…como el musguito en la piedra, ay si, si, si…” (Like Moss on a Stone), by Pina Bausch, 2012. Ph Stephanie Berger

The BAM audience has seen Bausch’s works move from harrowing to absurdist to delightful and loving. Three things draw us back: Her outsized imagination, her Dadaist sense of humor, and the dancing―the dancing. Although it’s not the first thing people talk about in Bausch’s work, some of the best solo dancing in New York happens in Tanztheater Wuppertal. Each member of the cast is stretched, windblown, urgent yet precise, and unique. One could complain that some of the solos are long and repetitive, but the actual dancing is superb.

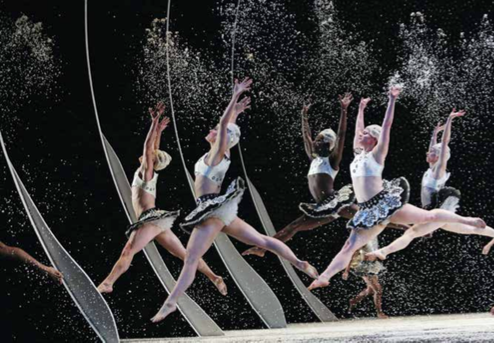

Hailing from Belgium, Anne Teresa De Keersmaeker’s Rosas has appeared in the Next Wave Festival almost as often as Tanztheater Wuppertal. More interested in momentum and less in theater, De Keersmaeker makes works that rev up minimalism into a fury of pure movement. She has partnered with Steve Reich’s music many times, as they share an approach to building complexity. Fase, a work for two women that she performed with dancer Tale Dolven at Steve Reich @ 70 (2006), was first developed in the early 1980s in New York at the studios of New York University’s Tisch School of the Arts. She took Lucinda Childs’s vocabulary of walking, twisting, and turning and imbued it with emotional intensity. The result was what New York Times reviewer Siobhan Burke calls “stark euphoria.”

Her collaborations with Reich expanded to larger ensembles with Drumming (2001) and Rain (2003). The rhythms were tantalizing and the dancing became more forceful—impulsive, highly inflected, obsessive. De Keersmaeker’s notoriety leapt forward in 2011 when Beyoncé’s music video Countdown appropriated some of the exact moves of the choreographer’s Rosas Danst Rosas (1986) from a YouTube clip. Charges of stealing hit social media, setting off widespread debate about the uses and abuses of appropriation.

Vortex Temporum, Anne Teresa De Keersmaeker: Rosas:Ictus, 2016. Ph Robert Altman

De Keersmaeker’s special brand of momentum reached an invigorating peak with Vortex Temporum (2016). The music ensemble Ictus played Gérard Grisey’s score of the same title with its spectacularly de-crescendoing notes (imagine a siren sounding backwards with a myriad of textures within it) on a bare stage. Later, the musicians and dancers together created a terrific centrifugal force. Moving in concentric circles, they were so commingled—all wore dark outfits—that it was hard to discern the difference between the dancers and the musicians. That confusion added to the excitement of the gathering whirlwind of sound and motion, their orbits crashing and clashing. One dancer even shoved the pianist off his bench, and somehow the piano ended up careening around the stage while being played. It felt like the performers were veering off into a solar system of their own.

Continu, Sasha Waltz & Guests, 2015. Ph Julieta Cervantes

Although Tanztheater Wuppertal and Rosas have performed at the Next Wave Festival more regularly than any other dance group, visitors from Europe have included a wide variety of choreographers: Mechthild Grossmann, Susanne Linke, Maguy Marin, Jiří Kylián (Nederlands Dans Theater), the French-Albanian Angelin Preljocaj, and the astonishing mixed-nationality hip-hop duo Wang Ramirez. The German dance-theater practitioner Sasha Waltz mesmerized audiences with the visually stunning Körper (2002), followed by Impromptus (2005), Gezeiten (2010). Her most recent Next Wave production, Continu (2015)—with its long dresses, explosive gestures, and Edgard Varèse’s dissonant music—took us back to the early drama of modernism.

But one of the most enduring and powerful influences from Europe has been William Forsythe. The American-born choreographer who revolutionized ballet in our time presided over Ballett Frankfurt and later The Forsythe Company for more than 30 years. He stretched and twisted and interrogated classical ballet until it became utterly contemporary and often bizarre. He used pointe shoes not to float but to jab into the floor. Some saw the super-attenuated, aggressive bodies as distortions, but those extremes were based on classical épaulement. In 1998, EIDOS:TELOS jolted us with the essential wildness of Forsythe’s choreography. The Ballett Frankfurt dancers thrust themselves into space, constantly interrupting their own movement as though trying to rid the body of something awful.

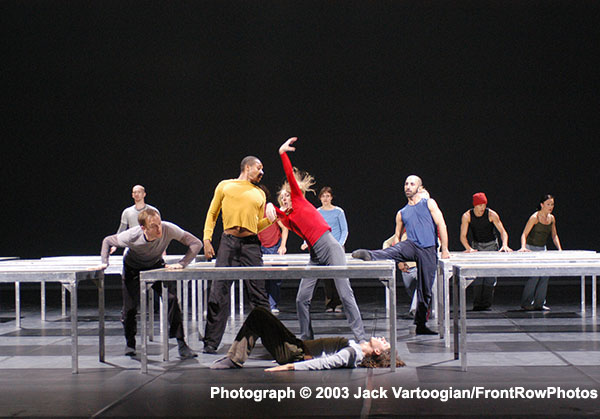

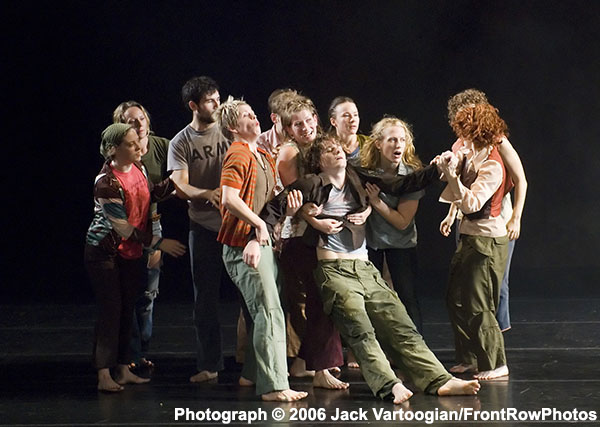

Ballett Frankfurt dancers in Forsythe’s “One Flat Thing, reproduced” © 2003 Ph Jack Vartoogian/FrontRowPhotos. All rights reserved.

In 2003, the final program of Ballett Frankfurt before it transitioned into The Forsythe Company included three galvanizing works. Twenty metal tables screeched into place for One Flat Thing, reproduced. The dancers crawled and lunged and pounced over and under the tables, creating a swarming hive just this side of chaos. They seemed to have a terrific urge to investigate the tables, unleashing their inventiveness into a very purposeful search. In a different vein, (N.N.N.N.) was a cause-and-effect sequence wherein four men fit into each other’s nooks and crannies like a puzzle. The most pristine piece was Duo, a duet mostly in unison, danced by two women in sheer black tops. With a spare soundscape by longtime Forsythe composer Thom Willems, it lays bare the powerful legs, destabilized pelvis, and extreme torquing of the upper body that characterize the Forsythe style.

Forsythe considers the stage a laboratory, and he’s experimented with radical new ways of generating and organizing material. In Decreation (2009), he used a device to “conduct” the dancers from backstage, thus varying their timing on the spot. It was Forsythe’s of-the-moment attention to the performance/audience relationship that determined how he conducted. Similarly, in Sider (2013), the dancers were listening to scenes from Hamlet through earpieces, and Forsythe’s voice would interrupt the Elizabethan cadence to guide them in speed and structural options. Just as Bausch was a leader in dance-theater, Forsythe exerted similar influence over post-classical ballet, which continues to be felt here and in Europe.

Epic Narrative

In the 1990s, African American choreographers felt a pull toward narrative as a means to tell their stories, which some have argued was a natural rebound from formalism. Dance scholar Ann Cooper Albright has called this direction “epic narrative” and points to four choreographers, all of whom have visited the Next Wave Festival, working in this capacity: Jawole Willa Jo Zollar, Garth Fagan, David Roussève, and Bill T. Jones.

Zollar’s Praise House, performed by her group Urban Bush Women in 1991, was based on the life of visionary black painter Minnie Evans, but the larger story was the profound black experience of turning suffering into joy. Praise House drew upon African American cultural traditions, including shouts and field hollers, to tell the story of an artist alienated from the church. Carl Riley’s gospel music infused it with a sense of place and time.

Nora Chipaumire of Urban Bush Women in “Les écailles de la mémoire” (“The Scales of Memory”) Ph © 2008 Jack Vartoogian/FrontRowPhotos. All rights reserved.

Zollar embarked on a more complex project in the 2008 Next Wave with Les écailles de la mémoire (The scales of memory), a collaboration between the all-female, Brooklyn-based Urban Bush Women and Senegal’s all-male Compagnie Jant-Bi. A major effort to understand Africa diasporan cultures, the collaboration itself was epic. The men don’t just dance, they go at dancing. Yet Urban Bush Women dancer Nora Chipaumire―who returned to the Next Wave in 2012 and 2016 with her special brand of gender chutzpah―gives them a run for their money. She taunts, yells, and out-dances them.

Other images refer to slavery: Men struggling with their hands clasped behind them as though trying to free themselves from shackles, heads bowed in supplication; women and men standing on a bench as though being sold at auction. The lighter moments see women strutting their stuff for the benefit of the men. One man does an amazing ass shimmy. The common ground between the male Africans and the female African Americans is well earned, gradually arrived at, and full of humor.

Valentina Alexander and Norwood Pennewell in Griot New York, Garth Fagan & Wynton Marsalis & Martin Puryear, 1991. Photo courtesy of BAM Hamm Archives

Garth Fagan’s Griot New York, which premiered in 1991 and returned in 2012, explores a remarkable range of tones and moods. Fagan merged the Caribbean tradition of storytelling with the American sculptor Martin Puryear and jazz great Wynton Marsalis. Fagan spices the techniques of Merce Cunningham, choreographer Lester Horton, and ballet with a sensual twistiness and mischievous pelvis. In a dance that’s a cross between a funeral dance and vaudeville, Natalie Rogers sashays and skitters onto the stage, does a slow and viscous solo with stretched classical lines, and then breaks it up with angular elbows, flexed feet, and jittery twitches: a seamless amalgam of cultural tropes.

Griot New York also contains one of the most casually tragic scenes in memory. It portrays homeless people either running around frantic or lounging around stoned. During the long section, one dancer inches slowly along the floor. A limp figure sprawls across his lap. Is he sleeping; is he dead? They stay together as they make their way from one side of the stage to the other, surrounded and sometimes hidden by the general commotion. Eventually, we see that the prone figure has some kind of palsy: His hand is shaking. Fagan, who also created the dances for The Lion King on Broadway, is a choreographic griot telling a story that doesn’t shy away from suffering.

David Roussève (featured) in The Whispers of Angels, David Roussève: REALITY, 1995. Ph Dan Rest

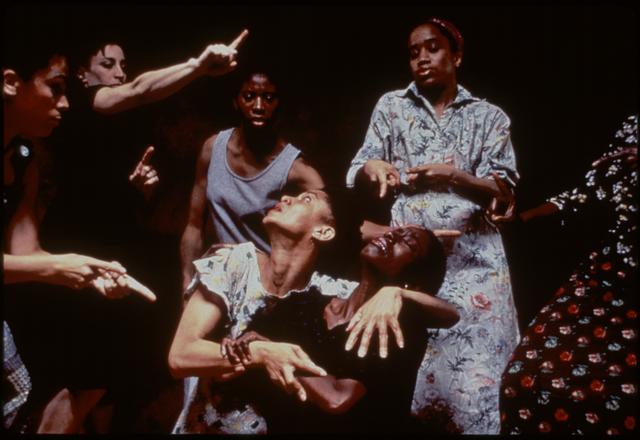

Another seasoned storyteller, David Roussève, has choreographed three epic narratives for the festival, all in the BAM Harvey Theater (formerly the Majestic Theater): Urban Scenes/Creole Dreams (1992), The Whispers of Angels (1995), and Love Songs (1999). Each one has a hard edge—nothing goes down easy with Roussève. He can catch you in the middle of a heart-warming tale and dip it in acid. In Whispers of Angels, he teamed up with jazz queen Meshell Ndegeocello, gospel singer B. J. Crosby, and filmmaker Ayoka Chenzira to tell stories of black folk from previous centuries. He spliced an annoying account of auditioning for a soap opera with painful stories of plantation life. Not one to simply celebrate black culture, Roussève, as the narrator, said lines like, “I stopped believing in everything black because everything black stopped believing in me.” His stage is populated with different generations and types. Funny can be brutal and brutal can be surreal. Angels, ancient people, eccentric characters, innocent children: All are subject to the harshness born of slavery, but the ultimate message is one of hard-earned hope.

Bill T . Jones in Still Here, 1994. Ph Joanne Savio

Bill T. Jones’s Still/Here (1994) was an epic narrative, followed by an epic debate. The piece paid tribute to those who died or were dying of AIDS or other terminal illnesses. Gravitas had replaced chic in his work. With Last Supper at Uncle Tom’s Cabin/The Promised Land (1990), Jones emerged as a leader of the multicultural side of the so-called culture wars. Deeply affected by Zane’s death from AIDS, and infected with the virus himself, Jones planned Still/Here to include material from his survival workshops, in which people with terminal illnesses articulated their fears and hopes. These participants would be seen in projections, and their words would provide text for the professional dancers to speak. He wanted to learn from what they were going through. Like his fabricated man in Secret Pastures, he was open, absorbent, and vulnerable.

When the press release went out saying that there would be videos and text taken from people with terminal illnesses, dance critic Arlene Croce had a fit. Her attack on Still/Here, published in the New Yorker under the title “Discussing the Undiscussable,” turned the piece into a cause célèbre. She refused to attend the performance, not wanting to see “dancers I’m forced to feel sorry for because of the way they present themselves: as dissed blacks, abused women, or disenfranchised homosexuals—as performers, in short, who make out of victimhood victim art.” Letters poured in to the magazine, some defending her choice and others defending Jones’s right to make art out of whatever was preoccupying him.

This debate reverberated around the country and has become required reading to understand the culture wars of the 1990s. Croce was railing against the oncoming inevitability of multiculturalism and inclusion in the arts. But beyond the debate, Still/Here became known as a cri de coeur in the age of the AIDS crisis. With his small group of diverse dancers, Jones managed to project hope, wisdom, and humor. The dancers recite phrases taken from the survival workshops, each time announcing the name of the participant first. Still/Here is epic in that it plumbs the mysteries of life and death in a poetic way. The quotes and gestures transcend the deadly circumstances to attain a kind of universality. Still/Here is a requiem, which, of course, is a time-honored form in music, theater, and dance.

Modern Takes Root and Branches Out

Ever since 1952, when Harvey Lichtenstein studied dance with Merce Cunningham at Black Mountain College, he was convinced that Cunningham was the future of modern dance. In 1954, when most of the dance establishment was dismissive of Cunningham, Lichtenstein offered him his first full evening of performance in New York City. Later, in 1968, he named the group a resident company at BAM. Long-time Cunningham dancer Carolyn Brown says the opportunity gave the choreographer “a kind of security that Merce had never known.” The company performed there many times, the last being The Legacy Tour at the 2011 festival.

Second Hand, included in The Legacy Tour, Merce Cunningham Dance Company, 2011. Ph Stephanie Berger

Cunningham and avant-garde composer John Cage had blasted open the relationship of music and dance. They created the two parts independently, bringing them together only for performance. The two men, who were partners in their personal lives as well as their artistic lives, never aimed to impart a single meaning or message, but were open to various interpretations. The Cunningham style of clean, unmannered, multidirectional movement was paired with experimental, sometimes cacophonous music by Cage or one of his colleagues. Not only was there no clear narrative, but the structure shunned the typical A-B-A format that was so reliably legible in most ballet and modern dance.

True to form, each of Cunningham’s Next Wave outings contained some sort of unorthodoxy. The soundscape of Roaratorio: An Irish Circus on Finnegans Wake (1986) mixed Cage’s compositions based on pages from James Joyce’s epic novel Finnegans Wake with sounds of laughter, seagulls, water pouring, a dog barking. A cluster of onstage chairs provided a resting spot for the dancers, most often used by Cunningham himself, who was already showing signs of debilitating arthritis. In the program Forward & Reverse, staged in the 1997 festival, video artist Elliot Caplan embedded video monitors into surrounding walls in Installations. They formed such an unusual décor that Anna Kisselgoff called them “opaque windows.” The series also included the New York premiere of Rondo and Scenario, whose grotesquely lumpy costumes by Comme des Garçons designer Rei Kawakubo tested our faith in Cunningham’s open-mindedness.

Split Sides, which premiered at BAM in 2003 as part of the 50th anniversary of the Cunningham company, embraced chance in a very visible way. Each night before the show someone rolled the dice—onstage in view of the audience—to determine which half of the choreography would be first. They rolled again to decide the sequence of the music (either Sigur Rós or Radiohead), and again for the backdrop (by either Robert Heishman or Catherine Yass). We were watching chance in action. On opening night, Robert Rauschenberg and Carolyn Brown rolled the dice. We were watching history in action. The Legacy Tour, which criss-crossed the country for two years after Cunningham’s death, reprised Split Sides with old favorites such as Roaratorio, RainForest (1968), and Second Hand (1970), and later works including Pond Way (1998) and BIPED (1999).

The Poetry of Motion and Objects

No young dancemaker was untouched by the Cunningham/Cage influence. New Yorkers like John Jasperse, Wally Cardona, and Kate Weare have continued in the spirit of experimentation with a keen focus on the specificity of movement. They tend to have less interest in chance methods and more interest in creating a visual field that triggers certain tasks. Each of the choreographers deploys everyday materials to arrive at a poetry of motion and objects. All have the uncanny ability to create something out of basically nothing.

Miguel Gutierrez and John Jasperse in Giant Empty, John Jasperse Company, 2001. Ph Maria Anguera De Sojo

In Misuse liable to prosecution (2007), John Jasperse filled the stage of the BAM Harvey with hundreds of coat hangers and water bottles, creating a kind of homemade, random beauty. He applied a methodical approach to functional movement. In Giant Empty (2001) that approach rendered his nude duet with Miguel Gutierrez fascinating. The small adjustments of hands, feet, butt cheeks, and back of head formed interlocking parts of a two-person puzzle. Giant Empty placed the body in a liminal space between the sculptural and the sexual. In 2016, Jasperse created Remains, seamlessly incorporating touchstones from the history of Western culture into his sculptural formations and phrases.

Kathryn Sanders and Joanna Kotze in Everywhere, by Wally Cardona, 2005. Ph Stephanie Berger

In Everywhere (2005), Wally Cardona, took on a workmanlike demeanor as he placed wooden beams vertically in rows. When he started adding a beam horizontally on top of each stanchion to make T-shapes, the configuration multiplied and changed the space. The banging, thudding sounds of beams added to Phil Kline’s sound score. Eventually the beams were reshaped into a staircase that a female dancer perched on, in contemplation. A male dancer hovered over the first step, arms holding a beam high overhead. Then he put the beam down and—lest you thought Cardona would get sentimental on us—he sat on a step and turned away from her.

Kate Weare, impulsive and fierce, premiered Dark Lark, a series of solos, duets, and trios, in 2013. There is something mythic about these encounters but it’s still intimate enough for the Fishman Space. The mood ranges from a private sense of wonder to a primal urge to fight. The contenders seem locked in a needy/belligerent love/hate battle with each other.

Rules of the Game, Jonah Bokaer & Daniel Arsham & Pharrell Williams & David Campbell, 2016. Ph Stephanie Berger

Jonah Bokaer, who danced in the Cunningham company and choreographed opera for Robert Wilson, was the inaugural dance artist for the smaller, flexible Fishman Space at the BAM Fisher Building in 2012. Melillo encouraged him to create a different kind of viewing experience than in the Opera House or the Harvey Theater. For ECLIPSE, Bokaer and architect Anthony McCall placed the audience on four sides and filled the room with 36 light bulbs arranged in neat descending rows of six. The first row of spectators was seated inside that grid. The choreography and the installation were meticulously timed, and when Bokaer passed his hand in front of a bulb, he seemed to magically bring on a mini-eclipse. Four years later, Bokaer created Rules of the Game, with stunningly ominous film projections by his longtime visual collaborator Daniel Arsham and music by Grammy Award‒winning composer, Pharrell Williams.

Cynthia Oliver in BLEED, Tere O’Connor Dance, 2013. Ph Ian Douglas

Others, like Tere O’Connor and Jodi Melnick, both of whom also performed in the BAM Fisher, lend an elliptical quality to the postmodern sensibility. You really don’t know what’s going on until something big and dramatic hits you. In O’Connor’s BLEED (2013), we get fragments of ambiguous, whimsical behavior. Heather Olson kneels over a prone man, playing some sort of patty-cake game. She could be a nurse, a sister, a mother, a playmate. He could be dead or alive. Suddenly everyone’s running in a circle, looking upward as though expecting lightning, gathering force until Olson leads them into a diagonal where they seem to be fighting an earthquake. They are shaking as though electrified, as though they themselves are the lightning and the thunder, all connected to each other like the old tale of the golden goose. People drop to the floor one at a time: an apocalypse.

In a calmer, less agitated vein, Jodi Melnick―who danced at the Next Wave Festival with Nina Wiener in 1987―premiered Moment Marigold (2014), a trio for women. Deadpan but glamorous, Melnick moves with a kind of gliding femininity that is a mystery in itself. In this piece, the three women conjured a private world of crystalline gesture, with the help of Joe Levasseur’s ingenious lighting. But in the end there’s a chilling tenderness to the way they arrange each other on the ground, fanning each other’s hair out. Are they preparing to bury their best friends?

Other Next Wave artists like Susan Marshall and David Dorfman have taken postmodernism into psychological realms. Marshall first came to the Next Wave Festival in the Lepercq Space with a very physical piece: Interior with Seven Figures (1988). It depicts the struggle of relationships with a certain toughness. One man is bent over, holding a woman roughly, grappling with her changing position, trying to keep control over her, possibly to kiss her. She climbs him like a tree. It’s an arduous, unwinnable partnership: the awkwardness of human need.

David Dorfman, who performed in Marshall’s Interior, used some of that same grappling energy in underground (2006) at the BAM Harvey, but it’s between the central figure (a beleaguered Dorfman) versus the group rather than between partners. With his defiant stance and shouted questions, he veers toward the political, reliving questions prompted by the revolutionary Weather Underground when he was a teenager: Are you a pacifist? In a violent world, can you fight for peace? Is violence ever justified? Is your country worth killing for?

Mark Morris: Merging Dance with Musicality

In some ways, choreographer Mark Morris is a throwback to pre-Cunningham times. Devoted to the idea of music and dance “going” together, he tends to choose classical music—played live—and relies on its classical structure. This occasionally appears predictable, but in his best work—and he is fantastically prolific—the music and dance together gather force. We experience the wholeness of the work immediately and thoroughly.

By 1984, the year of Morris’s festival debut in the Lepercq Space, he was, according to Jennifer Dunning in the New York Times, “being talked of as the most solidly promising heir to the mantle of the modern dance greats.” His solo O Rangasayee, danced to an Indian raga, awed critics by the sheer chutzpah of taking on the role of an Indian classical dancer, as well as by the freedom of his dancing and the richness of his choreography. The conventional theme-and-variations format works for him: His inventiveness and humor keep tumbling out. He also gave us luxurious movement at a time when the postmodernists were keeping it simple. As Jeff Seroy wrote in the Paris Review, “Part of the genius of O Rangasayee is that it returns one of the oldest and hoariest of modern dance tropes—the exotic Eastern solo of Denishawn days—to its primal roots in the ecstatic.”

In 1990, Morris presented the New York premiere of L’Allegro, Il Penseroso ed Il Moderato at the BAM Opera House; the choreography breathes with Handel’s oratorio and yet allows Morris’s goofiness to creep in. Only Morris could get away with having people stand there with arms extended as tree branches, and three men being pulled by dancers as hound dogs. The big rounded arcs of the body hark back to Doris Humphrey and the free-flowing skips are pure Isadora Duncan. L’Allegro was brought back to BAM in 2001; when it was broadcast on PBS “Great Performances” in 2015, critic Alastair Macaulay referred in the New York Times to its “miraculous beauty.”

Morris is not afraid to be entertaining. The motifs, messages, and jokes are easy to follow. He presents a community in every piece, and it’s a community of fallible human beings, not the super virtuosic dancers we see on the ballet stage. The performers’ enjoyment is contagious, easily crossing the footlights.

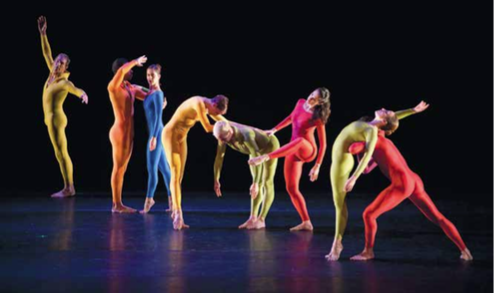

The Hard Nut, Mark Morris Dance Group, 2016. Ph Julieta Cervantes

The Mark Morris Dance Company is something of a fixture at BAM, and the work produced most often in the festival—six times—is The Hard Nut. Popular with both art audiences and families, it’s fun for the kids, and the adults chuckle every time they catch one character humping another in the first act. All the peaks and valleys, dangers and harmonies of the majestic Tchaikovsky score find their counterpart in Morris’s choreography. The bold black and white sets by Adrianne Lobel contrast nicely with Martin Pakledinaz’s riotously colorful costumes; both are inspired by a comic artist with a dark side, Charles Burns. Some characters, for instance the happy black maid, are a bit off key, but everyone gets the jokes. The Hard Nut is a relief for those who find other Next Wave offerings puzzling.

The gender play in The Hard Nut has more than entertainment value; it is part of an ongoing interest of Morris’s. In works like O Rangasayee, L’Allegro, and Championship Wrestling after Roland Barthes (1984), he rejects the obvious gender divide that is natural to ballet and modern dance and instead concocts an upbeat androgyny. In The Hard Nut, the corps of snowflakes—all-female in most other Nutcrackers—is co-ed, and they all wear two-piece tops and tutus.

The emotional center of this Nutcracker, however, is still the shy and tender Marie, a child full of wonder and idealism. All manner of jokey things happen to her, but in the final pas de deux she is swept up into young adulthood by love—with the help of all the crazy characters who return to usher her into her dream of romance. Morris wins us over with a sincere core surrounded by comical edges.

A Growing Hybridization

One of the unique aspects of Next Wave Festival is the prominence of collaboration wherein dance is just one element in the mix, illustrated by the influence of BAM “regulars” David Gordon and Big Dance Theater as well as intriguing hybrid productions such as Sarah Michelson’s DOGS (2006), Akram Khan and Juliette Binoche’s In-I (2009), and David Michalek’s Hagoromo (2015).

David Gordon, as much a playwright as a choreographer, has devised four dancing-and-talking productions for the festival—all with Gordon’s special brand of inquisitive irreverence. His grand opus, United States (1988), was co-commissioned by BAM and 26 presenters around the country. Gordon gathered written bits of local color from these presenters, to which he added movement material recycled from previous works. Included in this mélange was “Slaughter on Tenth Avenue” from On Your Toes, based on the 1948 Hollywood movie danced by Gene Kelly and Vera-Ellen. Naturally, former Cunningham dancer Valda Setterfield, Gordon’s wife and muse, played the Vera-Ellen character while Gordon approximated Gene Kelly. His character gets shot, setting off a corps of policemen—his own version of the Keystone Cops—who console the now widowed and veiled Valda. Like Trisha Brown and Lucinda Childs, Gordon was a founding member of the groundbreaking Judson Dance Theater of the 1960s. He is not beholden to any particular method but always engages his audience with a sense of play.

17c, Annie-B Parson & Paul Laza’s Big Dance Theater, 2017. Ph Rebecca Greenfield

The tiny Big Dance Theater, a true hybrid of dance and theater, presents vivid characters in a collision of genres and narratives. The directors, Annie-B. Parson (dance) and Paul Lazar (theater), create a collage of images that intersect each other. In 2014’s Alan Smithee Directed This Play: Triple Feature (a reference to Hollywood directors who didn’t want to claim a show they felt wasn’t up to snuff), the added component of film enlarged, foreshadowed, or echoed events onstage. The Dadaist landscape of Alan Smithee, complete with fur coats, long telephone calls, and cigarettes, could change from combative to docile on a dime. Shards of text from the movies Terms of Endearment and Doctor Zhivago interrupt other narratives, in the same sense that, as mentioned previously, William Forsythe’s dancers interrupt themselves physically. This kind of interruption, according to postmodern theory, wakes the brain up, even if the overall gist remains an enigma.

Next Wave hybrids have included three other intriguing productions at the Harvey. In Sarah Michelson’s absurdist DOGS, four dancers navigate huge spiraling sculptures and tree-sized sprouts of lighting instruments while engaging in a kind of mad hatter’s tea party; roast chicken was served to audiences at intermission. Akram Khan’s duet collaboration with actor Juliette Binoche entitled In-I infused questions of intimacy that touched on racist tropes with visceral struggles. The elegance and force of Binoche as a mover matched Khan’s vulnerability as a storyteller. And in Hagoromo, David Michalek’s enchanting vision for telling a Japanese Noh drama in music, puppetry, and dance, David Neumann’s choreography for ballet star Wendy Whelan distilled her essence to slowed down, other-worldly gliding.

Sarah Michelson’s DOGS, 2006. Ph Julieta Cervantes

Going Global

In the 1990s, Lichtenstein and Melillo started looking for Next Wave programming beyond Europe and embraced an international artistic perspective. They imported the calligraphic beauty of Taiwan’s Cloud Gate Dance Theatre, the intense ritual of the Paris-based Japanese butoh group Sankai Juku, and the cryptic imagery of Saburo Teshigawara from Japan. They also brought in the steady beat of Brazil’s Grupo Corpo and the rawness of Bangarra, the Aboriginal group from Australia. Each of these groups transported us to a different geographical and mental landscape.

Moon Water 2003 Ph Teng Hui-En

Another force that has taken the dance world by storm is Ohad Naharin and his Tel Aviv‒based Batsheva Dance Company. Just as Forsythe has redefined ballet, Naharin has turned modern dance inside out, giving us a staggering vitality barely contained by a sophisticated sense of form. Although precisely choreographed, his dances plunge us into an experience of humanity in a raw state. Gaga, his improvisational method or “movement language,” enables Naharin and his dancers to make wild, unpredictable movement that is true to their nature. Younger choreographers all over the world have been influenced by his unflinching investigations, and Gaga workshops are in demand as a training method that energizes all corners of the body.

Mamootot, by Ohad Naharin: Batsheva Dance Company, 2005. Photo- Julieta Cervantes

In 2005, Naharin brought the disarming Mamootot to the Next Wave, performing in the intimacy of a dance studio at the nearby Mark Morris Dance Center. In the brightly lit space, the Batsheva dancers, looking somehow caught off guard, are wearing something like tie-died long underwear. Nothing about these dancers is conventionally beautiful, but you sometimes find yourself gasping at the emotional beauty of the interactions. At one point a woman is lying down, while a nude man dances quietly near and over her. He kisses his own hand, then his knee, then the other knee but never touches her. Finally, she crawls up into his arms and he walks off with her slowly, her limbs dangling down. The mix of wonder and eroticism in Mamootot was called “pretty thrilling” by New York Times critic John Rockwell.

A sly sense of humor permeates the three sections of Three (2007). The penultimate scene has three sets of dancers lining up to take turns exposing different parts of their bodies. It’s a somber-to-silly depiction of the extreme vulnerability that’s essential to Naharin’s work. And then, to change the mood, they stride low to the Beach Boys song “Welcome.” As the lights fade, they are all still striding, threading through each other with purpose and direction, filling the space with a kind of rhythmic communal bliss.

Three, Batsheva Dance Company, 2007. Ph Richard Termine

In 2014, Naharin presented the bracing Sadeh21. A string of solos that expands to duets and trios, it can ricochet from tender to disturbing to soothing. One woman treads around the stage, hiking each hip up in a ridiculously distorted walk—for so long that it becomes second nature. One dancer tries desperately to latch onto another’s legs until she gives up hope. Just as your heart can contract watching these dancers, it can also expand. A small group of three people opens up to let another person into the circle, then another and another until the circle looks too big for the stage. Meanwhile, the hip-hiker is now treading in place.

Political Mother, Hofesh Shechter Company, 2012. Ph Julieta Cervantes

Naharin was neither the first nor the last Israeli dance artist to come to the Next Wave. In 1983, the festival invited Rina Schenfeld, a celebrated dancer/choreographer who danced with Batsheva before Naharin took the helm as director. Hofesh Schechter, who had also danced in Naharin’s Batsheva, brought his driving, tribal Political Mother in 2012. And in 2016, Zvi Gotheiner, who came to New York from northern Israel in 1978, presented a travelogue of sorts, On the Road, based on the Beat generation novel by Jack Kerouac.

Many choreographers have incorporated high technology into their work, but Gideon Obarzanek devised an especially spooky world in his Mortal Engine (2009). This piece from the Australian group Chunky Move started with digital animations of roving circles and ovals that somehow morphed into humans. Obarzanek and his team created the illusion that the dancing body generated light and shadow. Whenever the bodies moved, they seemed to be burning the space around them. Inky, smudgy shadows threatened to envelop the six dancers. With mesmerizing effects, Mortal Engine was a precise vision of gloom.

Ioane Papalii of company MAU performs in Lemi Ponifasio’s ‘Birds With Skymirrors’ Ph © 2014 Jack Vartoogian/FrontRowPhotos. All rights reserved.

Possibly the most global Next Wave participant, in the sense of far off as well as the sense of planetary precariousness, was Lemi Ponifasio’s Birds With Skymirrors (2014). The Samoan-born, New Zealand‒based Ponifasio sent monk-like men scurrying while making hieroglyphic gestures. A nude woman shouted warnings of impending doom. On film, a pelican rose up, straining to flap its wings in an oil spill. Although parts of the performance were inscrutable (or literally too dark to see), the message about an impending ecological apocalypse was clear. In the program notes, Ponifasio pointed out that in the Pacific Islands, climate change is “already here.”

Ralph Lemon: The Geography Trilogy

Unique among Next Wave offerings was Ralph Lemon’s monumental Geography Trilogy, spanning ten years. Lemon had danced with Meredith Monk but his early work was more formalist than imagistic. However, Monk’s interdisciplinary approach and her connection to the deep past had sunk in, and in going forward he was also going back. He decided to explore his own racial background by traveling far and wide. The trilogy comprises three different explorations into his artistic, ethnic, and spiritual history. For Geography (1997), the first installment of the trilogy, he traveled to his ancestral home of Africa; for Tree (2000), to his spiritual home of Asia; and for Come home Charley Patton (2004), to the racist United States South.

Ralph Lemon, Geography. 1997 Ph Tom Brazil

In an era when many artists were giving a mere nod to other cultures, Lemon was immersing himself geographically, physically, and artistically. His research produced three poetic evocations of time and place, each with its own balance of peace and turmoil. For the first part of the trilogy, he gathered four dancers and two drummers from West Africa and a Guinean storyteller living in Brooklyn. He had entered new territory and felt, he told me, “profoundly discombobulated.” The search for new materials and performers catapulted him way beyond his comfort zone. He ripped away stereotypes by giving the men cream-colored linen suits instead of either traditional African regalia or the bare-chested muscular look of, say, the Alvin Ailey company. Nari Ward’s curtain of recycled bottles and box springs transported us to a village of huts and dirt roads. Although Lemon cast himself as an exile from Africa (the structure was loosely based on the Oresteia), he often moved among his diasporic cast. While the West African performers did a stomping dance, torsos twisting, arms windmilling, knees flying up, Lemon himself was more swoopy, fluid, stretched. He danced with less of a beat, aloof from the pounding of the drums. He retained his postmodern self while still being one of the men.

But his postmodern “self” got interrogated and pelted. As Ann Daly wrote in the New York Times, “He has put post-modern dance on trial, and race is the grand inquisitor.” Sitting in a circle, the men argued with each other. A stylized fight broke out between two of them: head-butting, gripping, hurtling, and falling. Again and again. Lemon did not shy away from violence. Nor did he shy away from beauty. Ward’s gorgeous set, the rhythms of the drums, and the beguiling movement qualities came together to create a visual and cultural richness.

Tree, the second part of the trilogy, traced the route of Buddhism through Asia. The production was a collage of different cultures, languages, dances, and musics. Performers included men and women from Côte d’Ivoire, China, India, Japan, Taiwan, and the United States. Costume designer Anita Yavich’s extended their backpacks upwards with bicycle wheels that Lemon called “mandala vehicles.” We heard two simultaneous stories in two languages in two different parts of the stage. As a choreographer, he nearly crossed the line of disrespect: smoking on the same stage as classical Indian dance. Tree was more peaceful than Geography but also had moments of perverse cultural collision. A classical Odissi dancer was accompanied by African drumming. Two Asian men in blackface played traditional instruments similar to a harmonica and a banjo. Again, Lemon is pelted with stones. Was he making himself the target as atonement for transgressing against traditions?

Ralph Lemon’s “Come home Charley Patton” Ph © 2004 Jack Vartoogian/FrontRowPhotos. All rights reserved.

The final part, Come home Charley Patton, brought video into the mix. We saw Lemon, wading in water up to his waist while reading from a book. We saw the 99-year-old Walter Carter of Yazoo, Mississippi, get up and do a dance rooted in Africa. The cast was smaller—just four men and two women, all of them American except for the Ivorian dancer Djédjé Djédjé Gervais, a constant throughout all three parts. The sound score traveled through various blues songs and other music while the dancers shuffled with precise footwork in a forerunner of the “buck dance.”

There were odd, jarring juxtapositions. Okwui Okpokwasili sang Jacques Brel but then put iron horseshoes around her neck, harking back to captured slaves. She told a searing story about how in the fourth grade she and a white girl kept yelling the N-word at each other until the teacher informed Okwui that the other girl “can’t be a N-word.” A small screen placed high up showed an animation of James Baldwin’s face speaking in his real recorded voice. It was as though Baldwin were overseeing the proceedings.

While in the previous two pieces Lemon was pelted with stones, here he was assaulted by a fire hose, an echo of the famously brutal police response toward civil rights marchers in the early 1960s. It was viscerally shocking to see a blast of water trained on Lemon while he continued dancing, slipping and staggering under the force of the blast: dancing for survival.

The Geography Trilogy was more than one dance artist’s exploration into the past. It investigated the nature of what it is to be a global citizen, to not flinch at the painful contradictions that quest might involve. It also integrated the Next Wave audience racially. As Lemon said recently, “For the first time in my work, I was getting black people to my shows.” Obviously there was a personal satisfaction in this. But it reflects a larger accomplishment that BAM in general has been able to effect: integrating the audience.

Crossing Cultures

While not as long-term a commitment as Lemon’s Geography Trilogy, other cross-cultural forays include Karole Armitage’s Itutu (2009), Reggie Wilson’s Moses(es) (2013), and Seán Curran’s Dream’d in a Dream (2015).

Megumi Eda in Itutu, Armitage Gone! Dance, 2009. Ph Julieta Cervantes

Armitage collaborated with Burkina Electric, an African pop band led by composer Lukas Ligeti. Visual artist Philip Taaffe channeled the pop African blend into a series of backdrops depicting fauna with an almost predatory look. At times, with Peter Speliopolous’s kicky tutu-reverse costumes, the piece looked like a quirky fashion parade. The choreography sets African chest contractions against balletic leaps. The spirit of melding reached a poignant peak in a duet between the exquisite Megumi Eda and Zoko Zoko, a West African dancer who was part of Burkina Electric: a tender, patient, seductive sharing of styles and sensations.

For Dream’d in a Dream, instead of inviting other cultural traditions into his own craft, Seán Curran went toward them. Through the BAM-produced DanceMotion USASM, a program of the U.S. Department of State, the Seán Curran Company traveled to Bishkek, Kyrgyz Republic in Central Asia. There they encountered a traditional music ensemble called Ustatshakirt Plus. A former folk dancer himself (a champion Irish step dancer) as well as a former member of the Bill T. Jones/Arnie Zane Dance Company, Curran devised folk steps to mesh with the traditional mountain music. With nine benches onstage the dancers reclined and rested, danced and dreamt. When the musicians stepped downstage, we could see that their instruments were variations on banjos and recorders.

Dream’d in a Dream, Seán Curran Company: Ustatshakirt Plus, 2015. Ph Julieta Cervantes

In a recent conversation, Curran said that when he was invited to make a piece for the BAM Harvey Theater, he was thrilled. He thought back to 1987, when Peter Brook inaugurated what was then the Majestic Theater with his legendary production of The Mahabharata, and he knew he had to “fill the space” visually. Mark Randall, Curran’s longtime visual collaborator, hung a magnificent carpet of reds and purples to transport us to the region. The choreography was simple, nothing fancy, but fostered a warm feeling among the cast. While Itutu was bold and chic, Dream’d in a Dream evoked a sweetness from its dancers and musicians.

Like Lemon and Curran, Reggie Wilson gathers ideas as he travels. For Moses(es), which focused on the overlap between various Moses myths―including Zora Neale Hurston’s Moses, Man of the Mountain―and the African diaspora, he paid visits to Israel, Egypt, and Turkey. Wilson’s Fist & Heel Performance Group includes both dancers and singers, and, as in the African tradition, there’s a fluidity between singing and dancing. Sometimes Wilson sits on a chair stamping and clapping while the dancers follow along in what he calls his “post-African/neo-HooDoo” style. The music, as eclectic as Wilson’s influences, ranges from Louis Armstrong’s “Go Down Moses” to gospel, Egyptian, and Hebraic songs.

Moses(es), Reggie Wilson: Fist & Heel Performance Group, 2013. Ph Julieta Cervantes

Altered States

When a choreographer thrusts her or his dancers into the outer reaches of the imagination, they can plunge into extreme psychological states. Witnessing this kind of unmooring from the roots of sanity is partly what pulls us back to Next Wave again and again.

Josephine Ann Endicott cut a sordid, messy, over-the-top figure in Pina Bausch’s original Kontakthof. Excessive in every action and self-mocking to the hilt, she threw decorum to the winds. She was more than on the verge; she had tipped over the edge into a kind of insanity. The result was riveting, even alarming.

Eiko & Koma in their Night Tide, included in New Moon Stories, 1986. Ph Beatriz Schiller

The duo Eiko & Koma enter into another kind of extreme state. When they perform, they seem to be caught in a post-human apocalypse. Either the human world has self-destructed, or they are victims of a vast natural disaster. They have a visceral kind of need that stretches out time, and yet they command our attention. They create their own environment and then become part of it. For Night Tide, included in New Moon Stories (1986), Eiko & Koma’s inverted nude torsos resemble randomly placed boulders. In Tree (1988), they seem to be made of leaves. Collaborating with Native American musician Robert Mirabal for Land (1991), they thrash on parched earth; Koma pushes a bear carcass. Perhaps they are drowning in River (1997), one desperately trying to rescue the other. You can barely distinguish them as human: they are part of the driftwood. We, as audience, have to tap into our own powers of concentration in order to fully experience their super slow dive into the primal imagination.

Culturally, their work is related to butoh, the form that was developed in Japan during the United States occupation there in the 1950s. The New York‒based Eiko & Koma studied with Kazuo Ohno, one of the two founders of the form, and were devoted to him until he died. Extreme states, super slow pace, and a connection to nature are all characteristics of butoh. But they feel their work is independent, so they do not label it butoh.

In 2000, Eiko & Koma devised a cave-like environment for When Nights Were Dark. With the celestial sounds of a live praise choir and their typical slow motion, they could either be being born or dying. Sunlight seeps thru the stalactites as the whole “cave” makes one full rotation during the 75-minute performance. The two sink lower into the cave and rise up to come together, though you think it will be an age before they actually touch each other.

In William Forsythe’s Decreation, which is based on poet Anne Carson’s essay and opera of the same title, each member of his cast locates a center of madness within themselves. Toward the end, dancer Georg Reischl seems to break down before our eyes. He’s shifting on his feet and lamenting that his “spiel,” his story, is gone. As he expresses his torment at not being able to retrieve it, he cannot stop moving. In a talk after the performance, Forsythe explained that the idea of extreme states came from Carson’s view of mystics. He said of his dancers that “They are also contemplating the idea of these mystics in these extreme states. Carson calls it extasis. Georg’s misery is a kind of ecstasy at the same time.”

Djédjé Djédjé Gervais, David Thomson, and Darrell Jones in How Can You Stay In The House All Day And Not Go Anywhere? by Ralph Lemon, 2010. Ph Stephanie Berger

The second half of Ralph Lemon’s How Can You Stay In The House All Day And Not Go Anywhere? (2010) includes a 20-minute process of going past exhaustion. The five improvising dancers lose their bearings and their energy, yet they keep going because they can’t seem to remember how to stop. The flesh comfort among them—touching, leaning, supporting—provides a kind of harboring. In this case, the extreme state of the performers had its roots in Lemon’s real life. When he made this piece, he had just ended a long vigil over his lover, the Odissi dancer Asako Takami, watching life ebbing away from her. He recently told me, “I didn’t have the opportunity to think about anything other than this moment of dealing with a sick and then dying body. That became the work. I was watching this incredible genius dancer body falling apart, daily. In a weird way, a perverse way, I got to see that falling apart violently, horribly, and beautifully.” His state of mind seeped through the entire piece. The dancers, staggering and falling, weren’t “performing” anymore, they were just surviving. And we were there to witness it. One could call it anti-choreography, as Lemon had witnessed anti-life overcome his partner.

But Lemon wasn’t done with grief yet. After this section, Okwui Okpokwasili was onstage alone, sobbing honestly, ferociously, heartbreakingly for ten minutes. Lemon has said that she prepared for this ordeal by exposing herself to images of people suffering—and that she was a surrogate for his own mourning. Her crying jag was a tour de force that had a few people leaving the theater—but the rest of us glued to our seats.

The New Wave: Transgressive, Gritty, Interactive

As Next Wave favorites wind down—the Cunningham company folded two years after his death; Trisha Brown’s company rarely performs on proscenium stages; Pina Bausch’s Tanztheater Wuppertal is in flux; and The Forsythe Company has disbanded—a new crop of choreographers has sprung up. Among them are Kyle Abraham, Faye Driscoll, and Nora Chipaumire. These three have shown the kind of stark originality the festival is known for. In the 2016 festival, they all made excellent use of the flexible Fishman Space, while also tackling difficult subjects

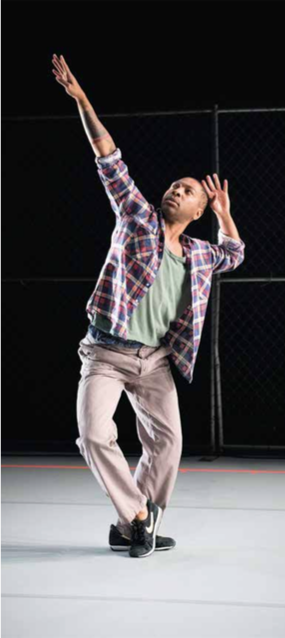

Kyle Abraham in his Pavement, 2016. Ph Ian Douglas

Pavement is Kyle Abraham’s poignant take on the 1991 John Singleton movie Boyz N the Hood, transposed to the Hill District of Pittsburgh, where he grew up. Abraham is bent on “investigating the state of Black America and a history therein.” The eight dancers of Abraham.In.Motion combine his mellifluous amalgam of hip-hop and postmodern improvisation with gently devastating images of police brutality. By the end, you feel familiar with the streets of the Hill District. The chilling “normalizing” of police profiling is met with a camaraderie born of survival instincts, all against a backdrop of music that ranges from Bach and Vivaldi to Sam Cooke and Donny Hathaway: an operatic array for a history of survival.

Faye Driscoll unleashes a kind of 360-degree zaniness in Thank You For Coming: Play. Audience members are asked to write words on slips of paper that are later incorporated in a lament: “Ohhhh X, Ohhh Y,” uttered in wonder and mock despair by Driscoll herself. In a section of astounding virtuosity, words and gesture are dislodged from each other and repeated with slightly different changes until finally the words and gesture match up. Driscoll, who has been influenced by both Tere O’Connor and Big Dance Theater, specializes in destabilizing whatever you thought was certain. The dancers change their costume and their tone in madcap succession. Talking about extreme states: Brandon Washington taps into his own lament, chanting over and over, “Where is my mom?” As he flails and bounces off the walls, it is somehow funny too, possibly because of the playful context. But like Georg Reischl in Decreation, he is caught in an ecstatic lament.

Nora Chipaumire with Shamar Watt and in portrait of myself as my father, 2016. Ph Julieta Cervantes

In portrait of myself as my father, which is part of BAM’s new Brooklyn-Paris Artist Exchange with Théâtre de la Ville, Nora Chipaumire thrashed against ropes that restrained her in a makeshift boxing ring. Head covered with a towel, midriff bared, wielding boxing gloves, she was chomping at the bit to break out of the box of one gender or another. She accosted the audience with growls, grunts, and accusations in French. We heard humiliating disses on black masculinity that her father, who was largely absent from her childhood, undoubtedly endured as a black man in Zimbabwe. She imagined herself teaching him how to get his swagger on. Senegalese dancer Pape Ibrahima Ndiaye leapt in and out of the boxing ring. Finally, Chipaumire bent over and lifted Ndiaye onto her back, saying, “I carry the carcass of my father.” Like Driscoll, Chipaumire excels at destabilizing, ejecting us from our center of comfort.

This tradition of discomfort continued in the 2017 festival with Germaine Acogny, known as the mother of contemporary African dance, who performed a solo choreographed for her by Olivier Dubois of Ballet du Nord that nearly unhinges her. A frequent guest at the annual DanceAfrica festival of African dance at BAM, Acogny brought her all-male Compagnie Jant-Bi to the 2008 Next Wave to collaborate with Urban Bush Women on Les écailles de la memoire (The scales of memory). Nine years later, she performed Mon élue noire (My Black Chosen One) Sacre #2, a driven solo to a recording of Igor Stravinsky’s Sacre du Printemps, in which she runs in place, pipe clutched in teeth, at a pace that would exhaust any other 73-year-old.

Making her Next Wave debut as a choreographer, Cynthia Oliver—who performed in Tere O’Connor’s BLEED—asked her all-male cast to dig beneath the stereotypes of black masculinity in Virago-Man Dem. She sometimes put them in situations that make them squirm but ultimately expanded their range of emotions and textures.

Another kind of boundary-pushing is the collaboration between video wizard Charles Atlas and former Cunningham dancers Rashaun Mitchell and Silas Riener. Tesseract extends Cunningham’s embrace of technology with 3D film and live video-mixing that ensures a heaping dose of chance. The six dancers were filmed, edited, and projected by Atlas in real time, making for some ghostly effects. Mitchell and Riener are Next Wave alums as dancers—both appeared in the Cunningham company’s Nearly Ninety program in 2009 and again in the Legacy Tour in 2011—but Tesseract was their Next Wave debut as choreographers.

To complete a full circle, Tanztheater Wuppertal Pina Bausch’s double bill that first wowed New York in 1984 returned to the festival. Bausch’s powerfully bleak Café Müller and her raging Rite of Spring shook New Yorkers and alerted the BAM audience that complacency had no place at the festival.

Pina Bausch’s Rite of Spring, Ph Stephanie Berger 2017

The waves of the Next Wave Festival will continue to bring stimulating artists to our shores, to reveal the depth and diversity of dance from near and far. Some of these artists consciously risk failure—and, let’s admit, it’s exciting to see how close they come to the precipice. But more than that, the Next Wave also reveals our own reactions, the varieties of method and madness within ourselves. While we return to the festival again and again because of our curiosity, we do not sit outside it, judging it from a distance. We are inevitably pulled into the arena—mentally and sometimes physically—whether it’s the Howard Gilman Opera House, the Harvey Theater, or the BAM Fisher. When we go to a Next Wave performance, we honor the curiosity within ourselves.

Historical Essays Leave a comment

Leave a Reply