When I moderated a panel called “Deconstructing Genius” last week at the 92nd Street Y Dance Center, I kept away from trying to define genius. All four panelists—Martha Clarke, Eiko Otake, Michael Moschen, and Elizabeth Streb—have received MacArthur fellowships, commonly called the “genius award” in the press. But the MacArthur Foundation never uses that word, and some of the panelists found the term less than useful.

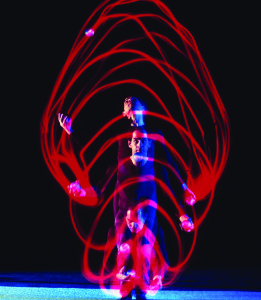

STREB’s Human Fountain at the London Olympics. Photo by Julian Andrews

What I see in these four amazing artists is a strong vision that allowed them to be utterly individual. More than that, they have each forged a path that eludes existing categories. They are the explorers of our time.

Now that the panel is over and I don’t have to worry about burdening anyone with that term, I want to name a few things that could qualify an artist as a genius—or at least an extraordinary artist.

But first the clichés

One cliché is that a genius is set apart from the rest of us, as the other, or somehow exotic, someone with a mind that’s beyond our understanding. Another one is that a genius is crazy. I just heard a radio voice refer to “crazy geniuses.” Those two words seem to go together in the public view. It’s unfair, and yet there’s a tiny germ of truth in that pairing. As Eiko said during the panel, “The line between genius and crazy is paper thin.”

Real attributes of extraordinary artists

But if there are geniuses among us, here are some attributes I would say mark such an artist.

• The first thing is vision—not necessarily a eureka moment, but a dawning over time. As Michael Moschen emailed me before the panel, “The world does not make sense, so I have to recalibrate in my own sensibility and make something that’s more truthful.”

• The second is curiosity—aimed curiosity. As each of these artists talked about their attraction to the unknown, they sounded to me like the great explorers—Marco Polo or Lewis & Clark—people who see a path that no one has taken, who have a sort of lusting for the unknown. Each of these artists have transgressed passed boundaries and transformed our idea of the performing arts.

• The third thing is plain hard work. As Eiko had said when I invited her onto the panel, “I am peculiar and a workaholic, but that doesn’t make me a genius.” I agree that those two criteria are not enough. But what Eiko doesn’t realize is that she—as part of the duo Eiko and Koma, and now on her own—has a third thing that is indefinable, and that is what makes her utterly unique. There’s no doubt that sheer hard work plays a role in bringing that uniqueness to light.

A Body in Fukushima, a series of photos taken by William Johnston of Eiko in Fukushima, a city irradiated and abandoned

Too-much-ness

But when Eiko was describing the late Kazuo Ohno, whom she does accept as a genius (to read Eiko’s beautiful obit on him, click here and scroll down) she talked about his “too-much-ness” and then admitted she also has this too-much-ness.

And that’s what rang true for everyone on the panel.

Alessandra Ferri & Herman Cornejo in Martha Clarke’s Chéri. Photo by Christopher Duggan.

When Martha Clarke described her piece Endangered Species, with Flora the elephant, a few monkeys and a horse, it sounded like too much. When Michael Moschen described the Chinese jugglers he learned from, their devotion to a single skill seemed too much. And Streb talked about the willingness to be impractical and “underground.” Although certainly her above ground actions—often high above ground—are wonderfully impractical. When you see Streb’s dancers leaping from great heights and making a pattern in space, that’s “too much”—meaning, overwhelming.

Michael Moschen, multi-exposure photo by Wayne Sorce

I think too-much-ness is the ability to go all out in one direction, to throw caution to the winds, to be totally immersed in your idea. Of course there are genius criminals too. And there are artists whose too-much-ness is merely “over-the-top” tastelessness.

But as Eiko pointed out, when the MacArthur Foundation sends a letter of congratulations to its chosen fellows, it thanks them for their contribution to humanity. So maybe genius is a too-much-ness that in some way elevates humanity. And then, and then…you have something to give to the rest of us.

Featured Uncategorized Leave a comment

Leave a Reply