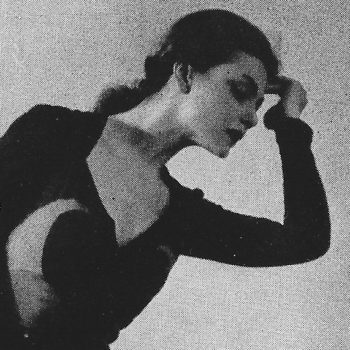

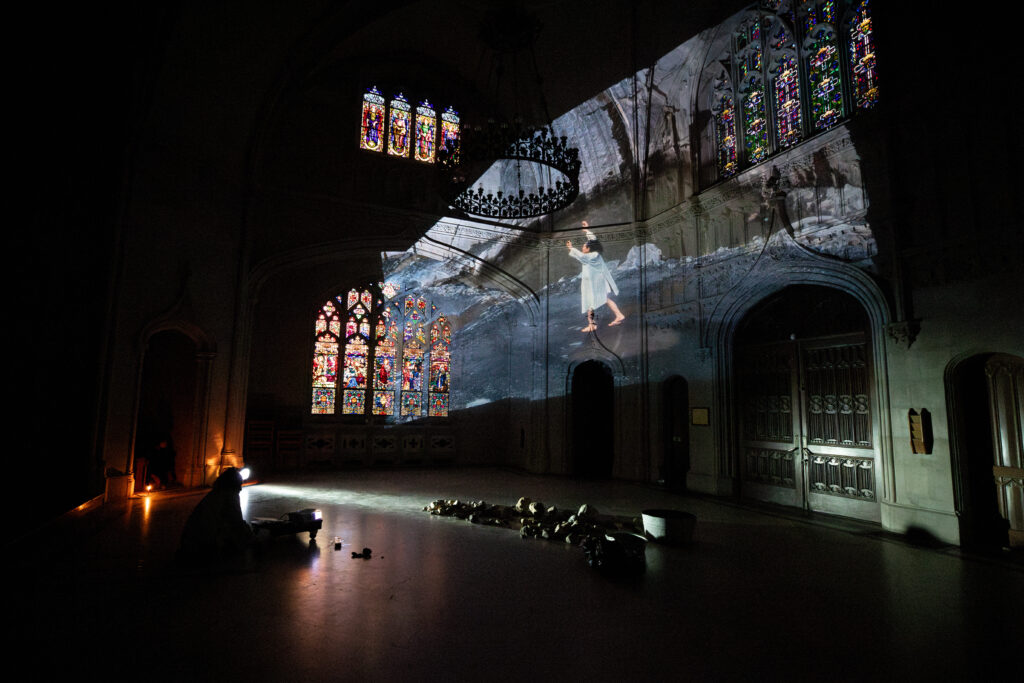

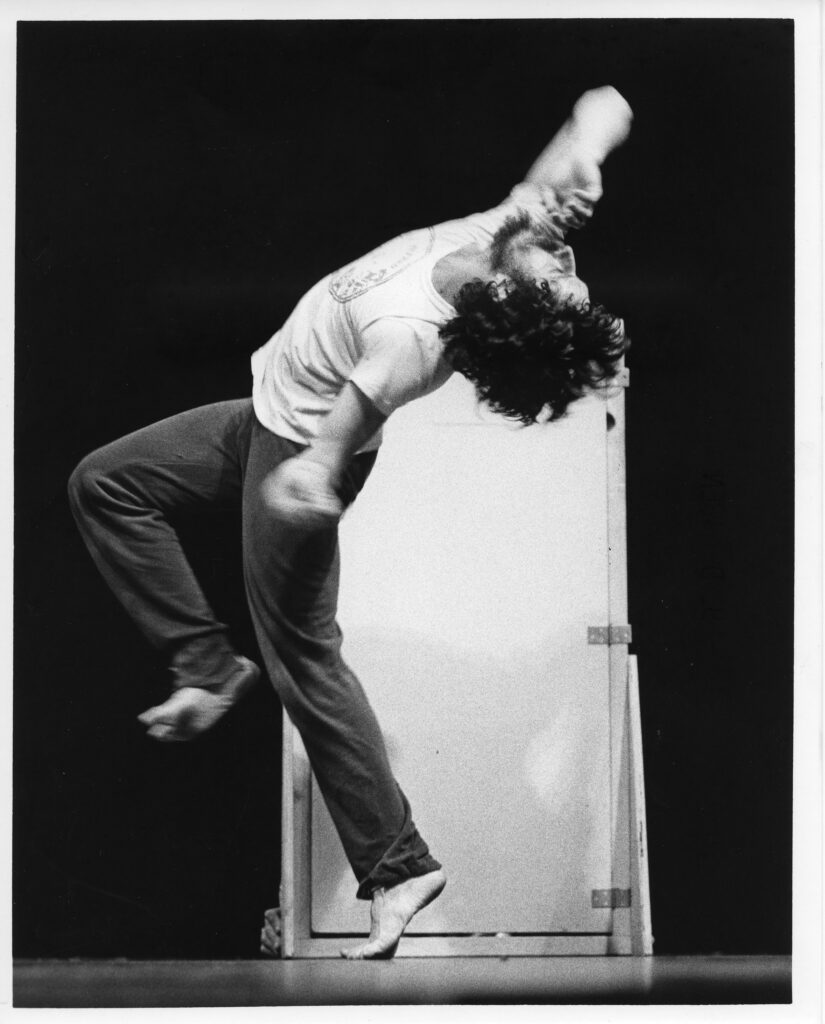

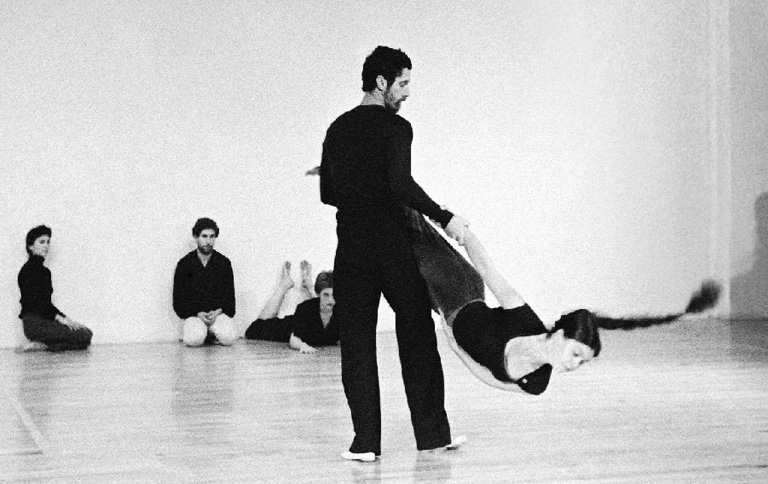

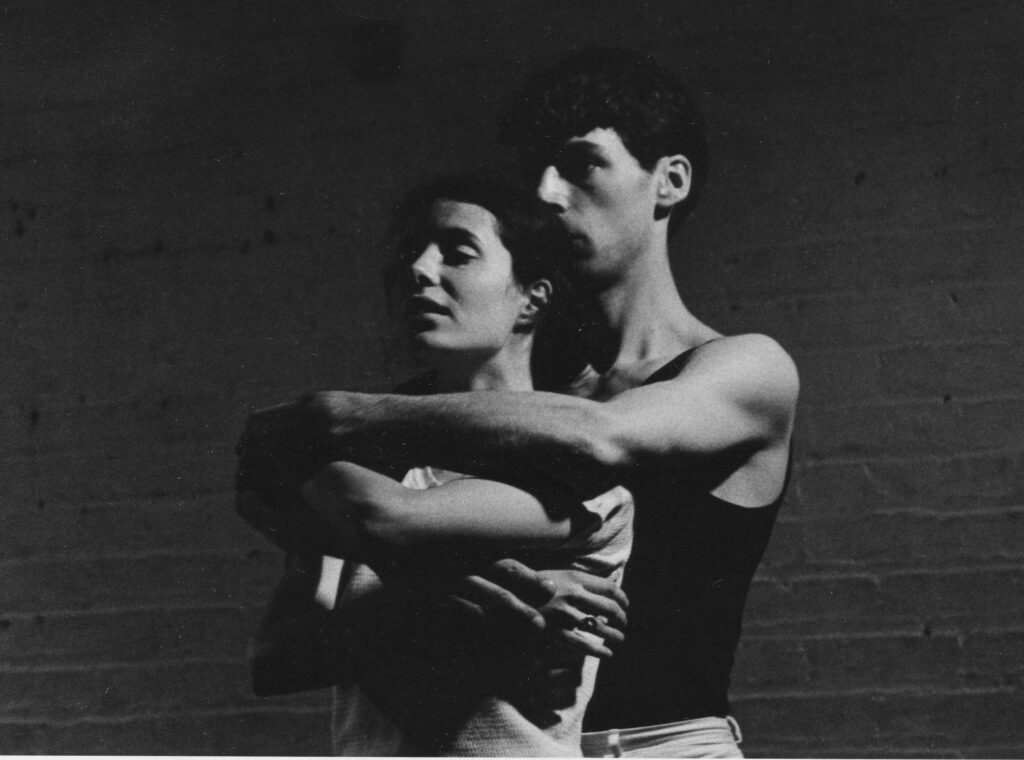

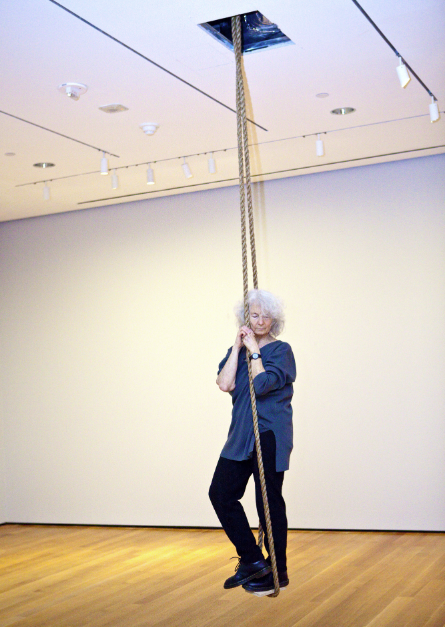

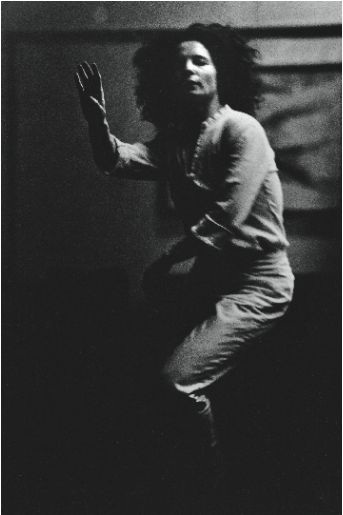

A ghost, an apparition, a figure somewhere between life and death, emerges from an alcove. Holding a candle, she touches the wall, as though to ensure that the physical world is really there. This wraith looks into the eyes of some of us witnesses sitting on the pews in this small, stained-glass windowed chapel.

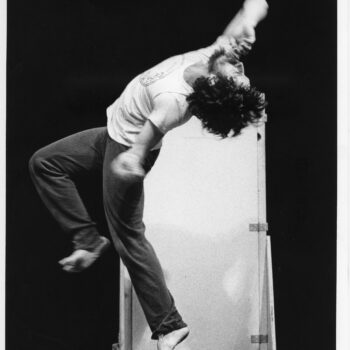

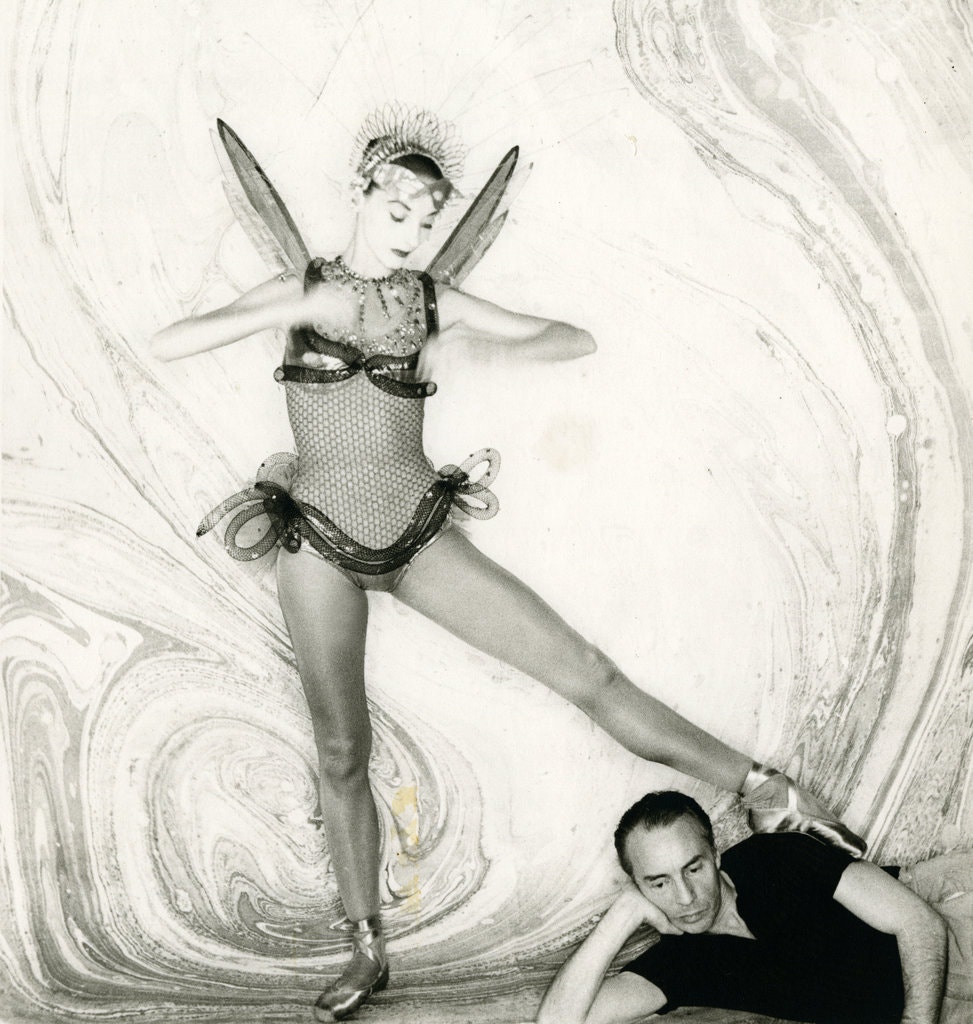

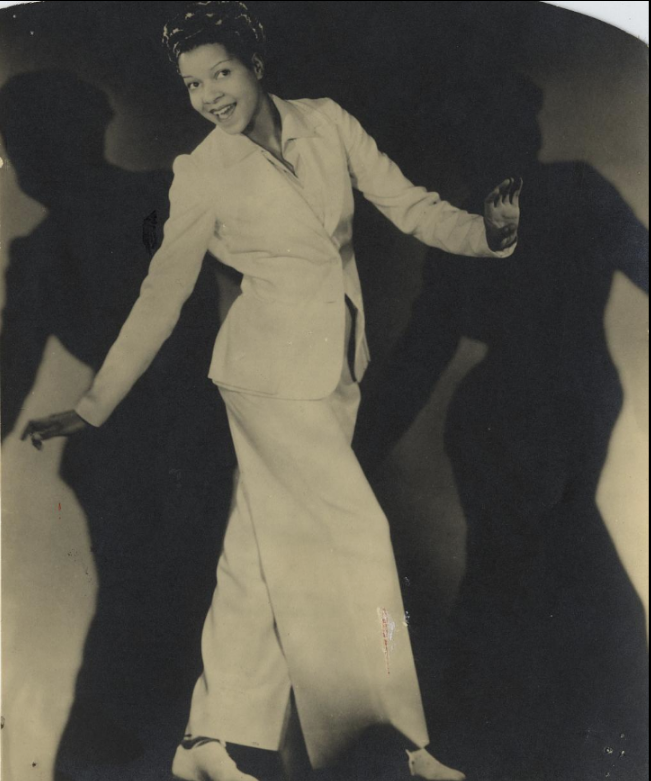

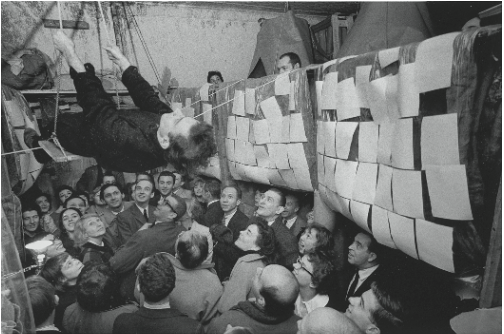

The image of Eiko in a quarry projected on the walls of the historic chapel at Green-Wood Cemetery. All photos by Maria Baranova

I’m watching Eiko Otake in Stone 1, a collaboration with avant-garde pianist Margaret Leng Tan at the Historic Chapel of Green-Wood Cemetery, June 28.

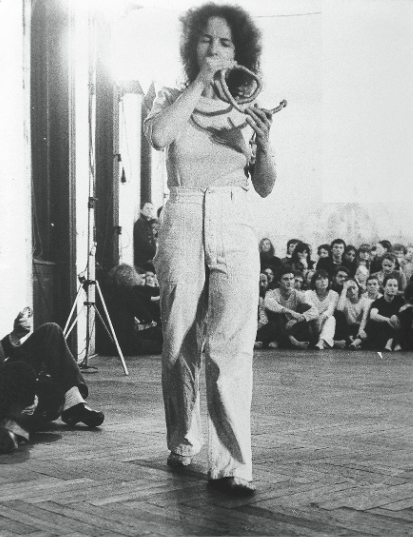

Because of the dimness, sounds help to define the environment. In another alcove, Tan gently plays the toy piano, blows a red bird whistle, and tips a rain stick to make the sound of wind or water. Sometimes we hear the crunch of pebbles or dirt landing on the floor. The sounds bring us closer to nature, and the music provides a path into Eiko’s memories.

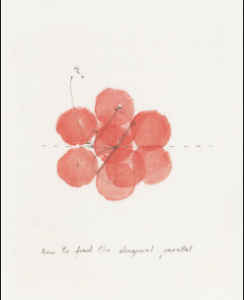

Eiko brings her history with her as she creeps or staggers around the room. We’ve already seen videos projected on the walls of this century-old chapel, sometimes with her tiny image amidst a massive quarry. This piece is all about stones—huge, medium, and small. Her quarry self, filmed last year in Sweden, seems to be in conversation with her three-dimensional self, both wearing beige raincoats.

Friends matter to Eiko. That raincoat belonged to an old friend, Sam Miller, who died in 2018. (See her Letter to Sam, where she talks about remembering the dead and how the coat came to her.) She dunks the coat in a bucket of water, lifts it up, and mightily wrings it out. Is she trying to wring life back into the coat? Stone 1 is dedicated to Alice Hadler, a recently deceased friend and colleague at Wesleyan, where Eiko is a visiting artist.

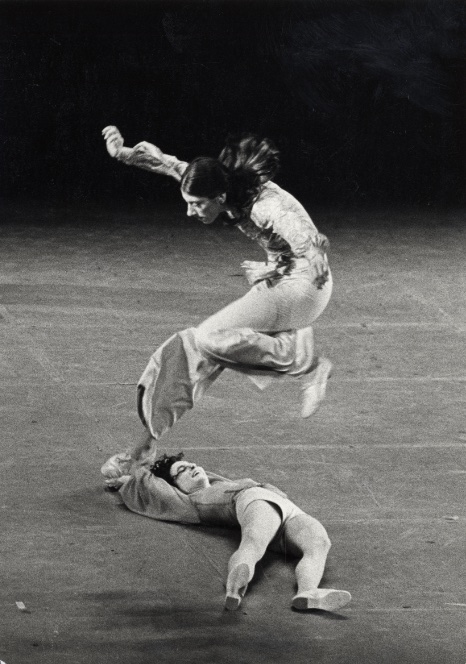

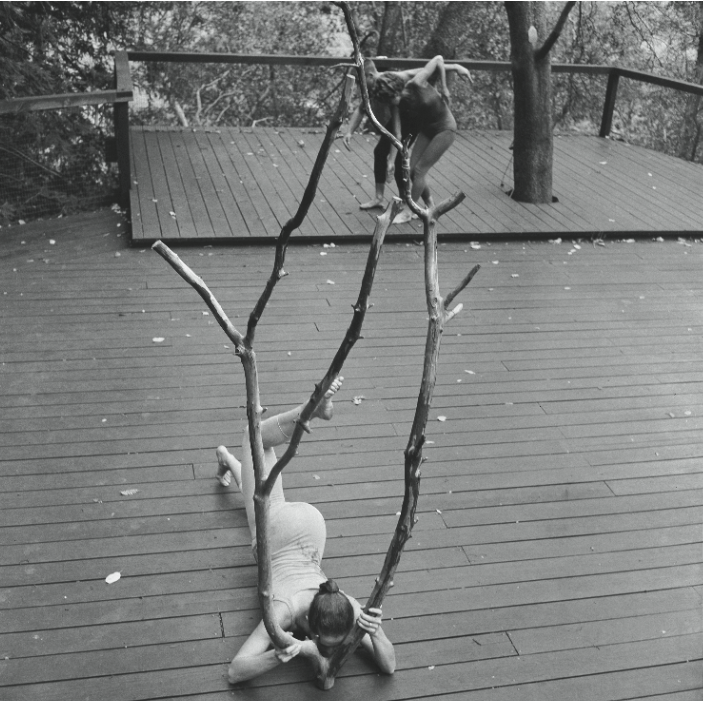

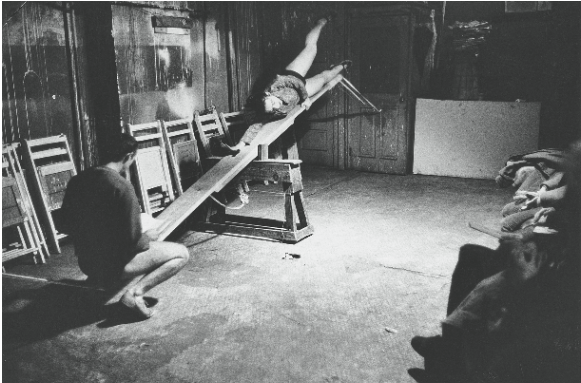

After thrashing around with the coat, Eiko climbs onto a pile of stones and lies down. I remember her saying in an interview, “I practice dying onstage.” Tan approaches and carefully places stones on Eiko’s torso. She then puts her ear to her belly. Perhaps Tan has healed her, because Otake rises, all four limbs floating upward.

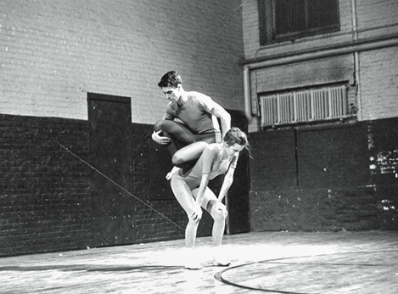

The piece has a special quality of touch: hands on walls, on stones, stone on skin, hands on doors, stones on body, head to chest, hands holding earth, earth holding bodies.

Eiko slowly opens the double doors to the outside, letting the nighttime in. We feel the enveloping darkness. A firefly darts in the distance. It occurs to me that this is the only place in the city where the doors of a performance space open onto complete darkness and quiet.

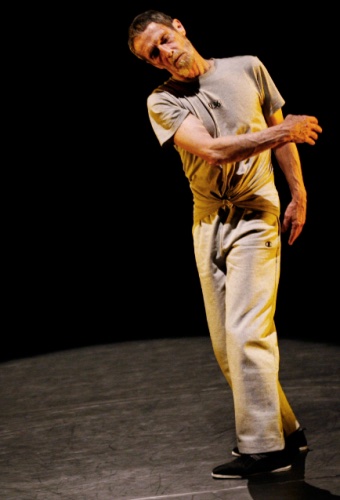

There is only one Eiko Otake. She is such a vivid presence that you never forget that this suffering, searching figure is Eiko. Yet what she is saying is universal. As she wrote in her book The Body in Fukushima, “We are breakable. All are fragile.” Although Stone 1 reminds us that death comes to all, there’s something spiritual in the idea that we share the earth with natural entities that last much longer than we do.

¶¶¶

Credits:

Music: Erik Griswold, Béla Bartók, and Bunita Marcus

Videos: George Rodriguez & Eiko Otake, Thomas Zamola for the Stone Quarry film shot at the Gylsboda Quarry in Sweden, via Milvus Artistic Research Center

Dramaturgy: Iris McCloughan

Featured Uncategorized Leave a comment

but was less than artistically fulfilling.

but was less than artistically fulfilling.

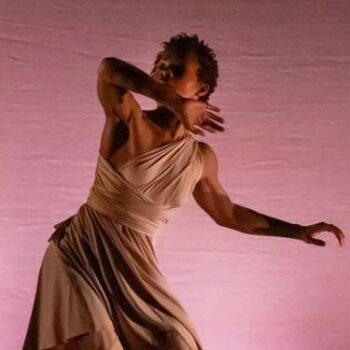

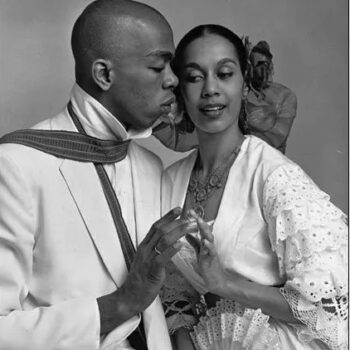

Dance We Do: A Poet Explores Black Dance

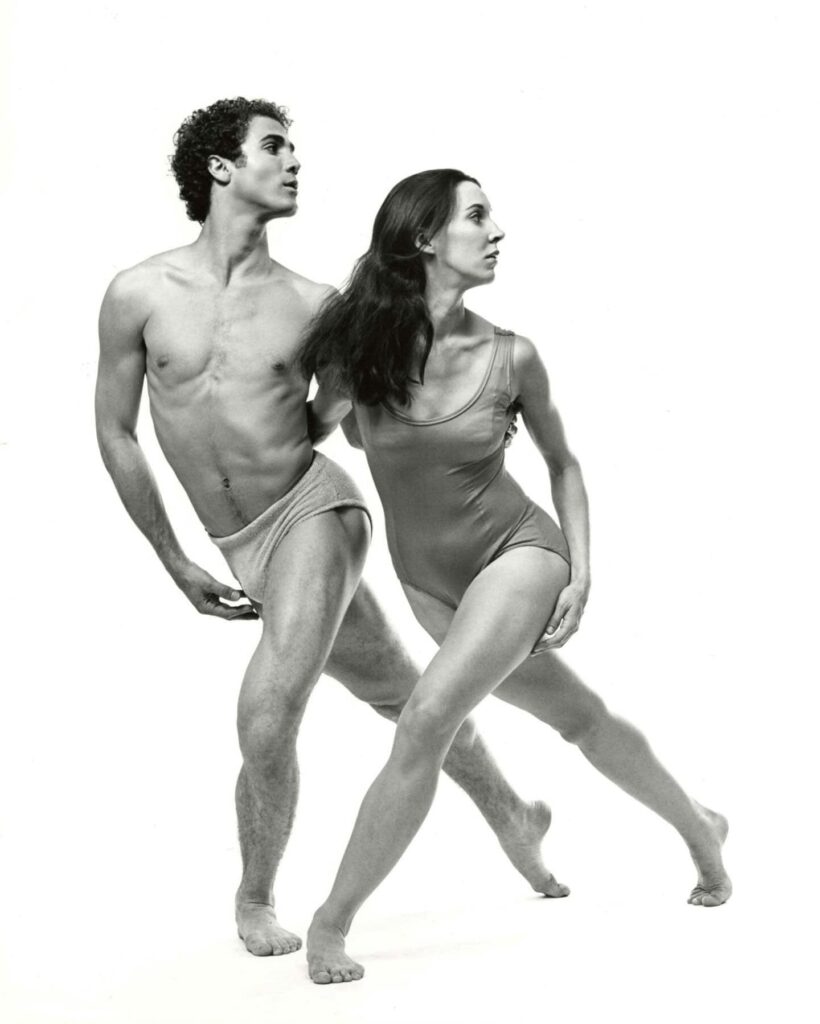

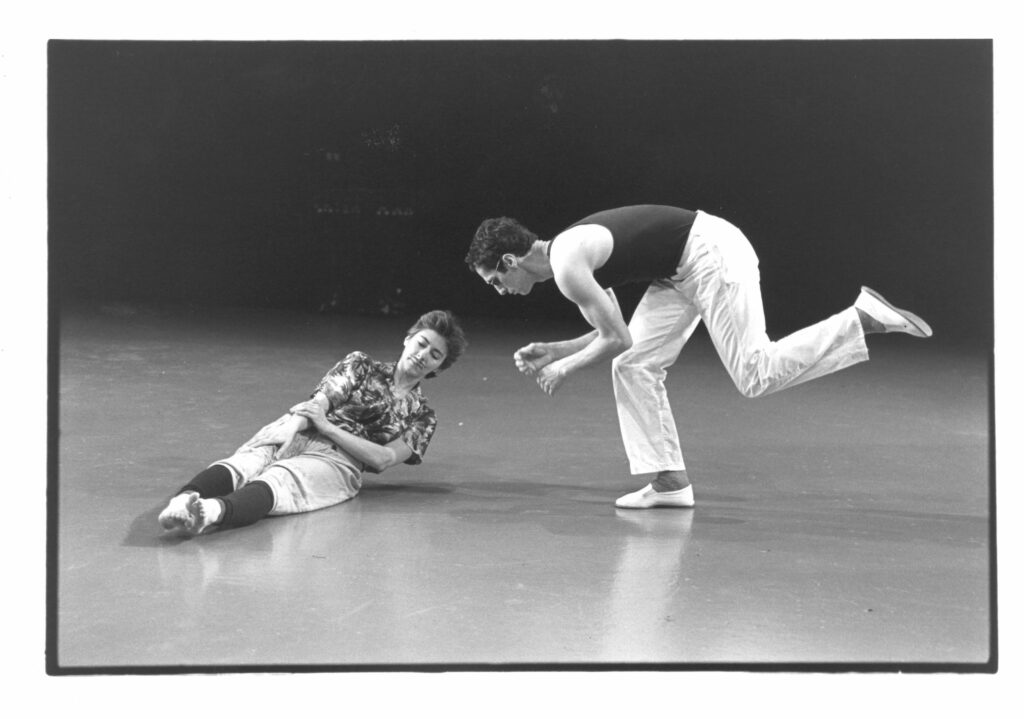

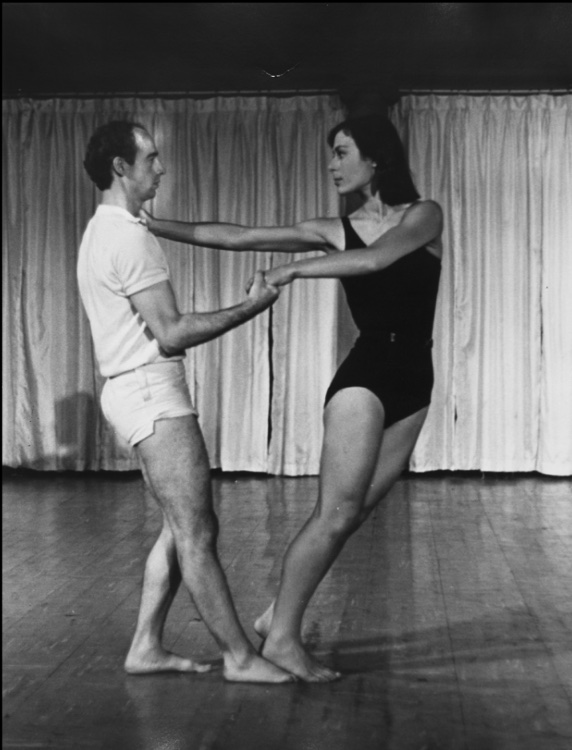

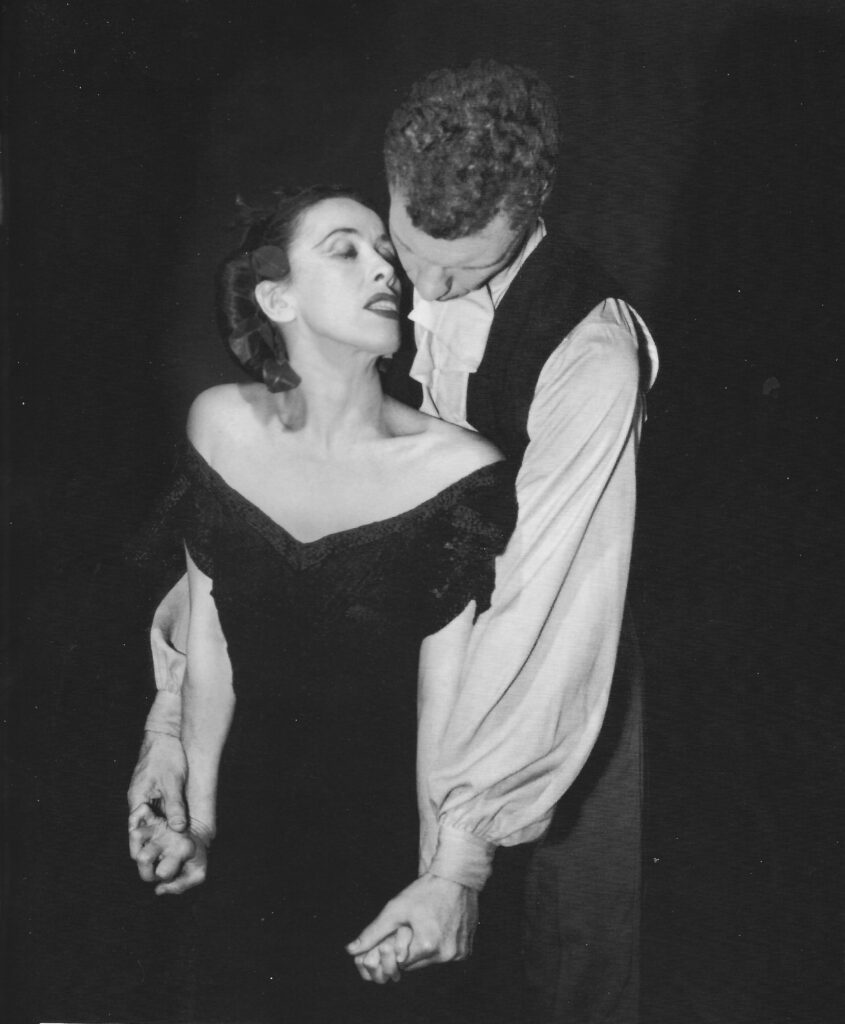

Dance We Do: A Poet Explores Black Dance Daniel Lewis: A Life in Choreography and the Art of Dance

Daniel Lewis: A Life in Choreography and the Art of Dance Final Bow for Yellowface: Dancing between Intention and Impact

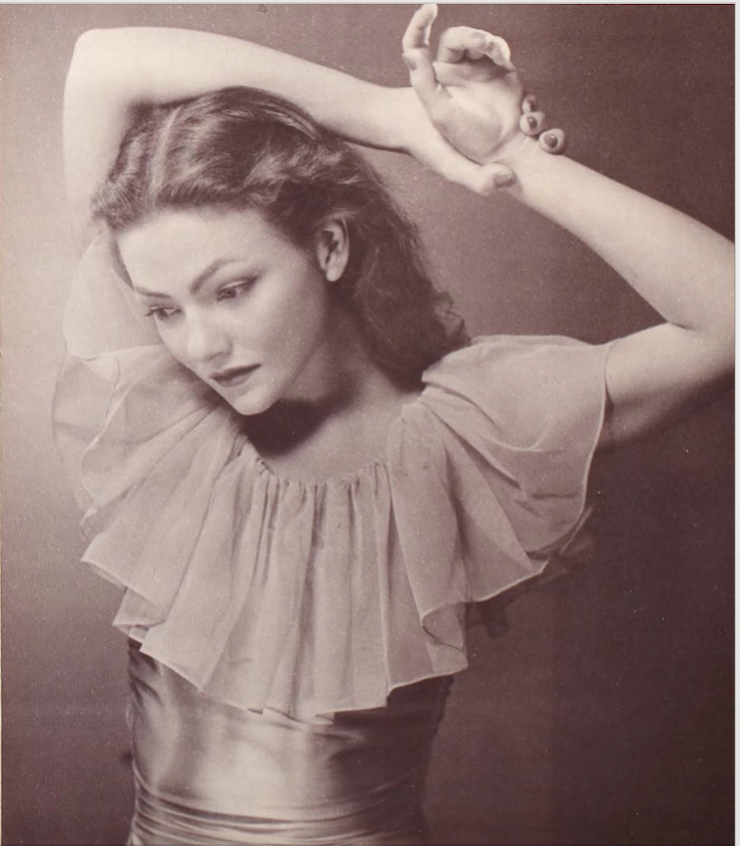

Final Bow for Yellowface: Dancing between Intention and Impact Martha Graham’s Cold War: The Dance of American Diplomacy

Martha Graham’s Cold War: The Dance of American Diplomacy The Fascist Turn in the Dance of Serge Lifar: Interwar French Ballet and the German Occupation

The Fascist Turn in the Dance of Serge Lifar: Interwar French Ballet and the German Occupation

The Legat Legacy

The Legat Legacy Futures of Dance Studies

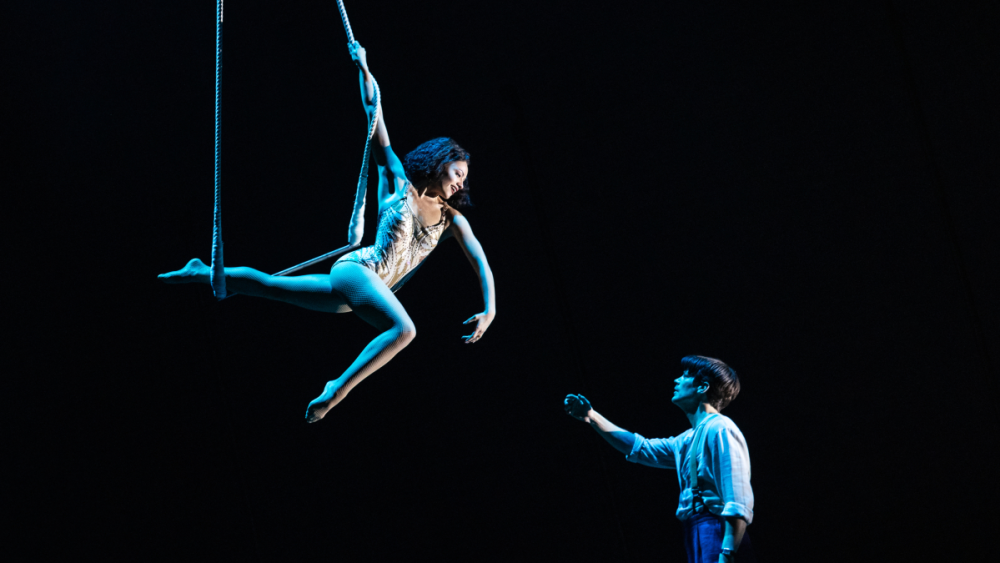

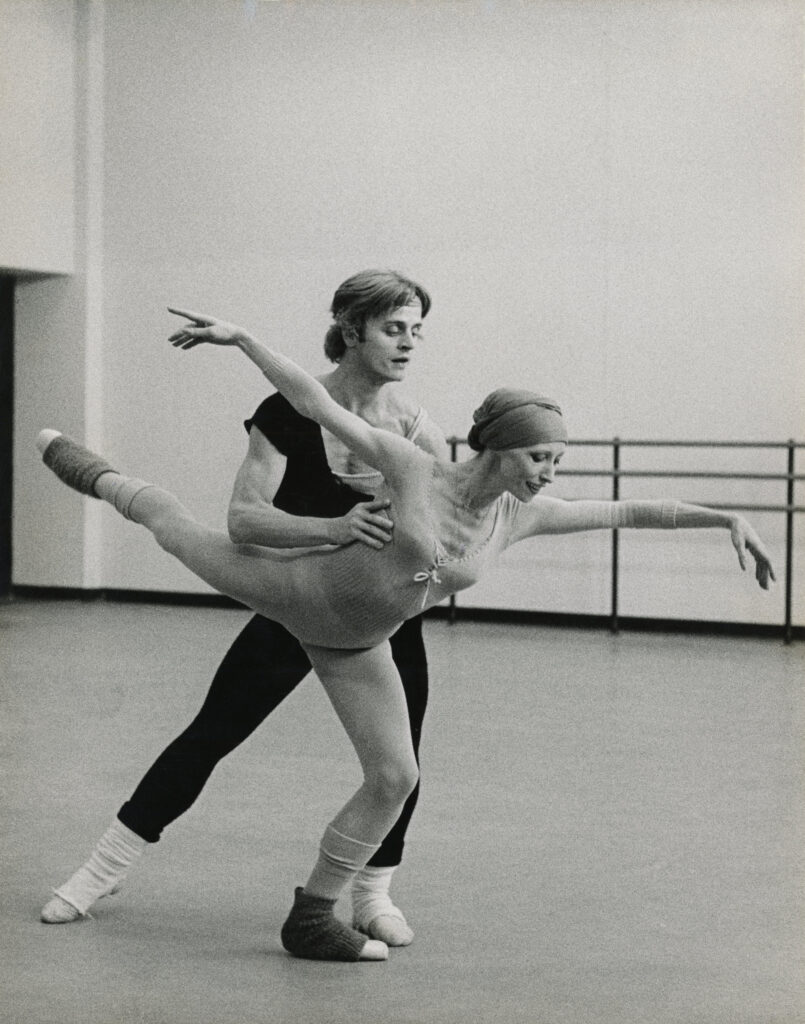

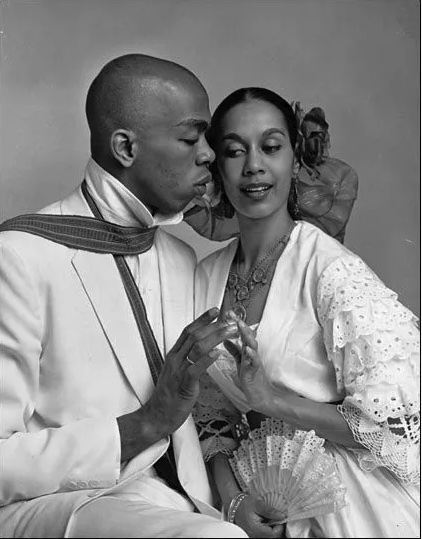

Futures of Dance Studies Ballet in the Cold War: A Soviet-American Exchange

Ballet in the Cold War: A Soviet-American Exchange Finding Balanchine’s Lost Ballets: Exploring the Early Choreography of a Master

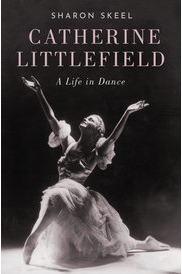

Finding Balanchine’s Lost Ballets: Exploring the Early Choreography of a Master Catherine Littlefield: A Life in Dance

Catherine Littlefield: A Life in Dance Moving and Being Moved

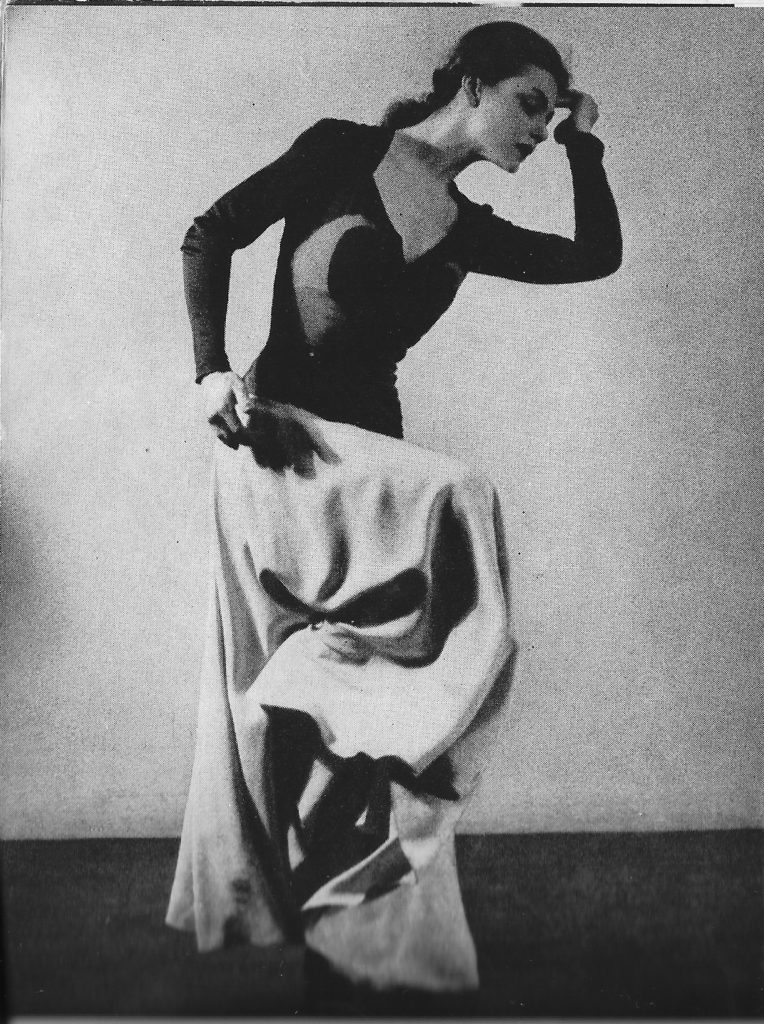

Moving and Being Moved Fringe: Maria Benitez’s Flamenco Enchantment

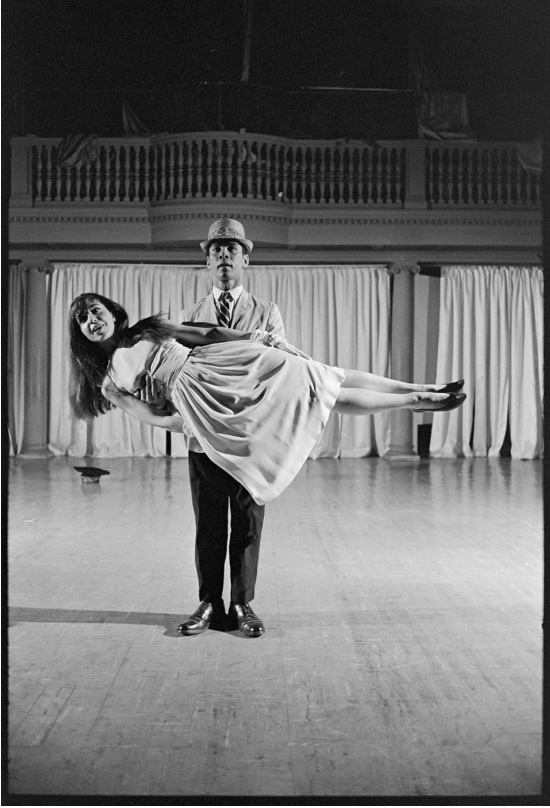

Fringe: Maria Benitez’s Flamenco Enchantment Yvonne Rainer: Work 1961–1973

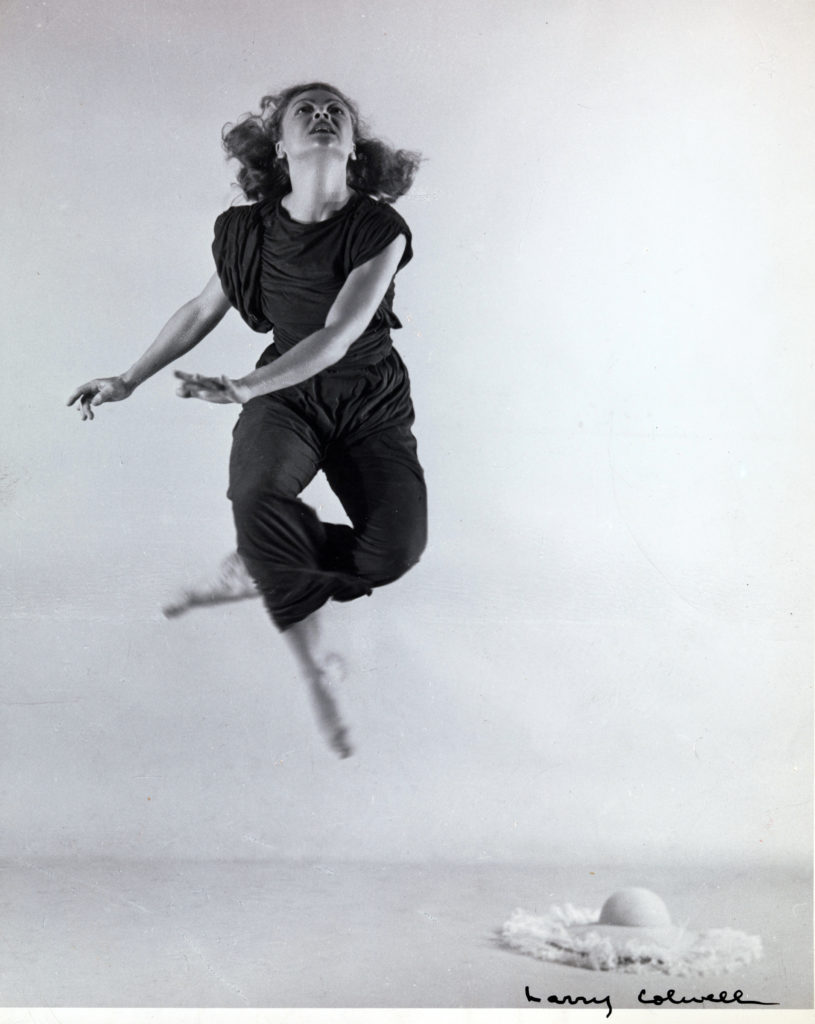

Yvonne Rainer: Work 1961–1973 Conversations with Meredith Monk

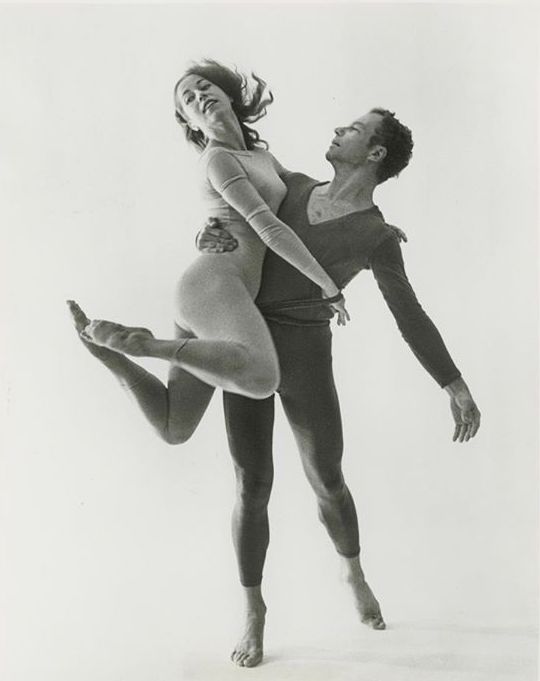

Conversations with Meredith Monk Howling Near Heaven: Twyla Tharp and the Reinvention of Modern Dance

Howling Near Heaven: Twyla Tharp and the Reinvention of Modern Dance