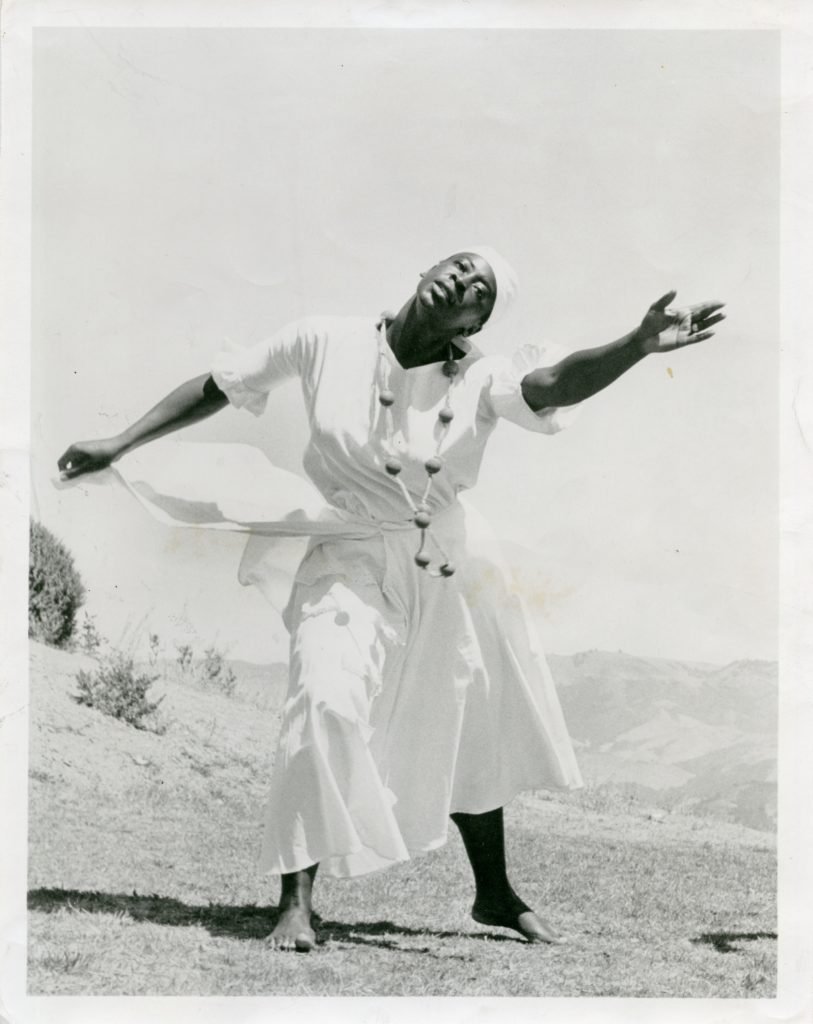

Beckford, 1961, Ruth Beckford Papers, African American Museum & Library at Oakland, Oakland Public Library (AAMLO)

The only dancer to have performed with both Katherine Dunham and Anna Halprin, Ruth Beckford developed a modern dance program for the whole city of Oakland, California. She trained and mentored countless young women in dance and in life, teaching with equal parts discipline and joy. Known as the “Mother of Black Dance” in the Bay Area, or just “The Dance Lady” in the East Bay, she also toured with her own African-Haitian dance company. A lifelong activist, Beckford broken color barriers wherever she went: as a child in dance lessons, in college, and in modern dance companies.

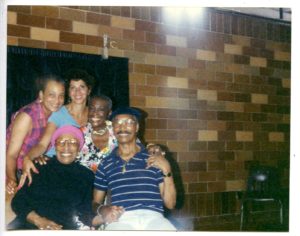

Beckford’s community was a family. Among her “daughters” were Naima Lewis, Deborah Vaughan, and Halifu Osumare. She called Maya Angelou and Anna Halprin her “sisters.” She was named Oakland’s “Mother of the Year” in 2018.

Beckford received many accolades: She was inducted into the Isadora Duncan Dance Awards (Izzies) Hall of Fame in 1985 and was honored by Geoffrey’s Inner Circle, a hub of the Black Arts Movement, the year before she died. As a visual tribute, the Alice Street mural in Oakland’s arts district features Beckford as a towering figure overlooking African American arts.

Early life

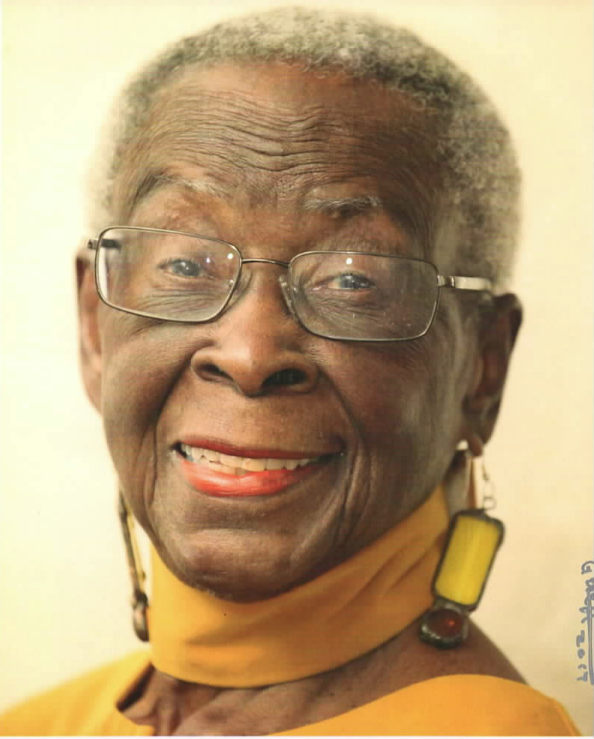

Ruth, photo courtesy Joyce Gordon Gallery

Born in Oakland, Ruth showed an urge to dance from the beginning. “My mother said that in the crib, if music played, I would start kicking in time with the music.” The youngest of four children, she was taking dance lessons with Florelle Batsford at the age of 3—the only black child there. She studied ballet, tap, and acrobatics — with a flurry of flamenco, hula, baton, toe-tap — for the next 14 years. To pay for the lessons her mother would clean the studio, and, as she got older, Ruth would pitch in too.

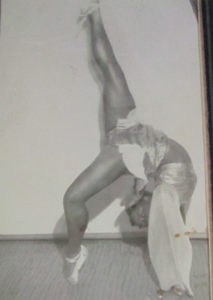

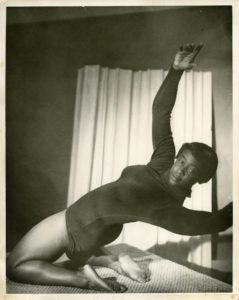

Comfortable in a split, Joyce Gordon Gallery

At 8, Ruth was earning money as an acrobatic dancer with her brother in local vaudeville houses, as well as winning a slew of solo dance competitions. Her father was an entrepreneur who owned his own taxi cab, then a simonizing business, and finally his own miniature golf course. As an active member of Marcus Garvey’s Universal Negro Improvement Association, he passed down black pride to his daughter. He would always tell her, “You are a fine young black woman.” This was a source of great security for her: “When you went out into the world with that on your back, nothing bothered you because you knew you could come home to those loving arms.” Ruth felt her integrated neighborhood in West Oakland was harmonious. “There were wonderful Black businesses all up and down Seventh Street,” she has said. (This was before it was gentrified.)

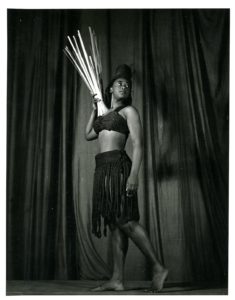

The young acrobat, Joyce Gordon Gallery

At 14, she started teaching in her garage: “For a quarter you could come and get 15 minutes of tap and 15 minutes of ballet.”

Her life coincided with great moments in history. Her sweet 16 birthday was celebrated on the day Pearl Harbor was bombed. “We all went to the movie,” she recalled. “We’re sitting in the movie eating milk duds … and on the screen the movie stopped, and it said all military personnel report to your bases, the United States is at war with Japan, and we are getting bombed.” One of the tragedies of the war for her was the loss of some of her friends to internment camps, a shamelessly racist chapter in America’s past. “Our best friends were Japanese kids. Then, when they got evacuated to their camps, we all cried; our friends were gone.”

Ruth, second from left, always loved a party, c. 1940s, Ruth Beckford Papers, AAMLO

Dancing with Miss Dunham

In Rite de Passage, Katherine Dunham Dance Company, 1943, Ruth Beckford Papers, AAMLO

Like the Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo, Katherine Dunham would give impromptu auditions while on tour. Egged on by her brothers, 17-year-old Ruth went to see the Dunham troupe in Cabin in the Sky at the San Francisco Curran Theater, where Dunham was co-starring with Ethel Waters. In her memory of that day in 1943, Ruth and her mother went backstage to meet Miss Dunham, who right away—in between the matinee and evening performances—arranged for her to perform for some of her cast members on the stage. “Accompanying myself with round metal discs on my fingers, I performed an acrobatic finger cymbal dance consisting of splits, flips, bends, and stretches, all done in slow motion to show strength, control, and a sense of rhythm.”

She was accepted into the company for its six-week West Coast tour. After obtaining a leave from Oakland Technical High School, Ruth started a three-week immersion:

Each morning I studied Dunham technique and each afternoon repertoire. Since Miss D always traveled with at least three complete shows, the challenge was tremendous. I can remember moving my feet to rehearse a new step while sitting on the “C” Key System train during my daily commute from Oakland.

Because Ruth was so young, Dunham invited Ruth’s mother to go along on this tour, which traveled up the West Coast to Canada and back down to San Francisco. Mrs. Beckford became a kind of den mother for the company. The tour was Ruth’s first time leaving California, first time on a ship, and first time seeing snow—not to mention her first time dancing Dunham’s works. At the end of the tour, Dunham offered the teenager a seven-year contract. It was tempting particularly because the company was on its way to Hollywood to shoot Stormy Weather. However, Ruth’s family valued education, and she finally decided to go to college instead of committing to a life on the road. As she said to Miss Dunham, “If I hurt myself, I’ll just be a dumb ex-dancer.” Dunham respected her decision, and the two women remained friends for life. Beckford even threw a 90th birthday party for her mentor in St. Louis.

Workshop with Dunham dancers, St, Louis, 1993. Clockwise from top left: Albirda Rose, Cleo Parker, Ruth Beckford, Tommy Gomes, and Lucile Ellis, Ruth Beckford Papers, AAMLO

A string of firsts

Ruth became the first Black member of UC Berkeley’s chapter of Orchesis, the modern dance society that had branches all over the country. When they would meet in larger gatherings, with other local schools like Stanford and Mills, there could be a hundred girls in a room. “The pressure of being the only black walking into a room with all white girls and all white teachers—if I hadn’t had the kind of support at home where I knew who I was and proud in being black—I don’t know what I would have done.”

Ruth in 1952, Ruth Beckford Papers, AAMLO

UC Berkeley faculty member Carly Cuddeback had attended the Bennington School of the Dance in the summers of 1936 and ’37. She had studied composition with Martha Hill and Bessie Schönberg and had appeared in the premiere of Hanya Holm’s Trend (1937). She was so impressed by Beckford’s talent that she brought her to the Halprin-Lathrop School in San Francisco, where Anna Halprin taught Humphrey-Weidman technique and Welland Lathrop gave Graham-based classes. Halprin and Lathrop invited Beckford into their company, which was a top-tier West Coast modern dance group at the time—before the Civil Rights era. “Everywhere we went,” Beckford said, “people weren’t prepared for a black dancer and they gasped. It was courageous for them to open the doors to an African American dancer back then.”

Beckford kept in touch with Halprin the rest of her life. When Halprin was working on her controversial, inter-racial work Ceremony of Us in 1969, she arranged for the black performers to study with Beckford. When I was working on a different research project in 2018, I was lucky to speak with Beckford on the phone. When I asked about Halrpin, she said, “Anna and I are still like sisters.”

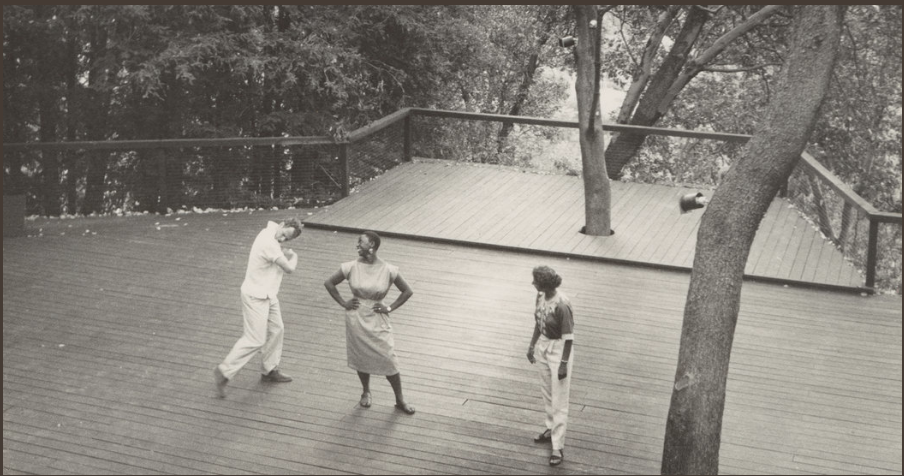

Beckford in center, Merce Cunningham at left, Anna Halprin at right, on Halprin’s deck, Kentfield, CA, 1957 @Ted Shreshinsky for Dance Magazine

The First City-Wide Dance Program

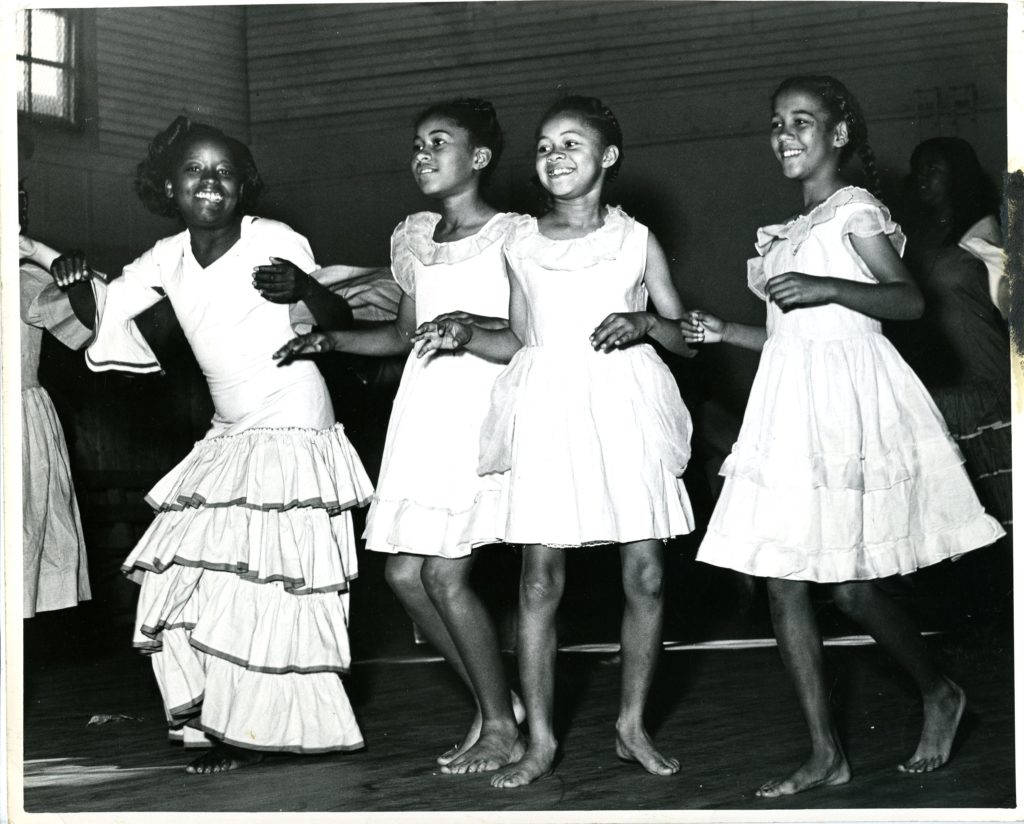

1955, Ruth Beckford Papers, AAMLO

After graduating UC Berkeley, Beckford took a job with the Oakland Parks and Recreation Department. She turned that minimal program into the first city-funded dance department in the country: the Oakland Recreation Department’s Division of Modern Dance. She set up classes at community centers all over the city for ages six up through high school. Her mission was less about training girls to be professional dancers and more about teaching to the whole child. As black dance scholar Halifu Osumare has written,

Her primary goal was to create productive, self-respecting young women through dance in social context, following one of Katherine Dunham’s primary philosophical concepts, ‘Socialization through the Arts.’ Here was a community dance teacher who had strict, graduated levels of technique with “dance exams” that had to be passed in order to go from one level to the next.

Beckford had a realistic view of her mission:

Only one will be a dancer out of all these hundreds of girls, but they all have to be women. So life skills I would always slip into the dance classes. The girls learned to stand straight, to have self-confidence, to not curse, not fight, and I tried to expose them to many new things.

First concert at New Century Recreation Center, 1947, Ruth Beckford Papers, AAMLO

Deborah Vaughan, director of Dimensions Dance Theater, told me in a phone interview how much Beckford’s students admired her:

She had a very infectious personality and was a fantastic dancer. But another thing that was impactful for us young Black girls: she was stunningly beautiful and she was very dark skinned and had a close-cropped natural. For so many young black girls, even today, with the wigs, with getting their hair pressed, often not accepting often who they are . . . We said, ‘Omigod, look at her, she’s beautiful.’

The program was so successful that people from around the country were sent to Oakland to observe the classes. It’s been said that other cities modeled their parks department dance programs on Beckford’s. This is probably true, but the only one I know of is in nearby San Mateo, where the Parks & Recreation Department Dance Program was started by Mary Joyce, who had taught with Beckford in Oakland. The program is still going strong, offering scores of live streaming virtual classes in the pandemic.

Undated photo of girls in the Rec program, Ruth Beckford Papers, AAMLO

In 1968, after 21 years at the helm, Beckford hand-picked her successor, Naima Lewis. In fact, she waited until Lewis finished her masters’ degree in dance from Mills College to pass the torch. Lewis, who is now an internationally certified yoga therapist, had come to the Rec program as an 11-year-old and joined her company (see next section) at 15.

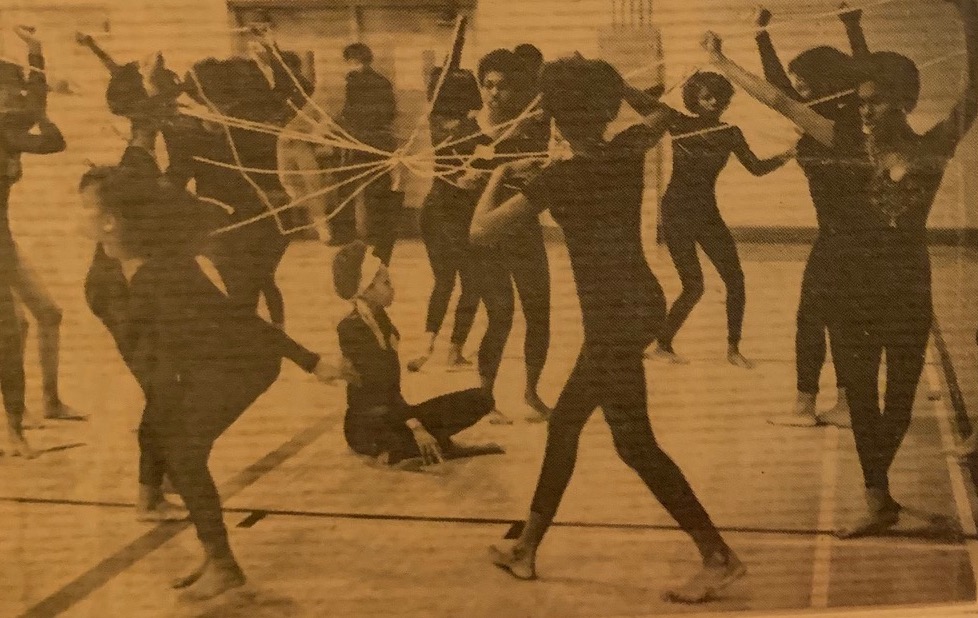

Naima Lewis teaches a class at McClimonds High School Gym, 1971, Newsprint photo courtesy Dr. Lewis

When she took over the program, it was the beginning of the Black Power Movement. So she decided to bring African-Haitian dance into the Recreation program, whereas Beckford had taught African-Haitian separately, in private studios. About the period when she inherited the program from Beckford, Lewis told me this:

It was the 1960s, and everybody was turning to Africa. The Oakland Rec Department was wide open for it. Miss B had nurtured in me the strength and the courage to step forward and say, “Now the revolution needs to be shown through black dance.’ It allowed young people to have a sense of ethnic identity. Without being too dogmatic, dance has this way of massaging consciousness into those that are participating. It was an opportunity to expand awareness of your own self and your own history, much like what is occurring now.

At that point the program was serving 350 students a week, from 6-year-olds up. “They could take dance for one dollar a year,” Dr. Lewis recalled. “When I took over, we tripled the staff, with Deborah Vaughan, Shirley Brown, and Elender Barnes.

After Lewis left in 1978, the program was led by the late Raymond Johnson and then Jacqui Birdsong James. By 1988, when Denise Pate took over the program—by then called City-Wide Dance program— it served thousands of children, from kindergarten through high school, in sixty sites, employed eight to ten musicians, and more than twenty dance teachers. But in 1993 the program was split up and the full-time position director position was eliminated. Pate, who is now the city’s Cultural Funding Coordinator, says that the “remnants of the dance program” can be found in a few classes at the Oakland Sports and Aquatics Center and many more classes at the Malonga Casquelourd Arts Center, which is the hub of Oakland’s performing arts community. Deborah Vaughan’s Dimensions Dance Theater, Axis Dance Company (a mixed-ability group), and Diamano Coura West African Dance Company are housed there. (Originally called the Alice Art Center, it was renamed after Congolese dancer/drummer Malonga Casquelourd was killed in a car accident in 2003.)

The Ruth Beckford African-Haitian Dance Company

In 1954 Dunham invited Beckford to New York to teach at her famed midtown school. Beckford felt honored to be on the same faculty with Geoffrey Holder, Arthur Mitchell, and Louis Johnson. But the school’s days were numbered because the director, Syvilla Fort, left to start her own school. So, after two months, Beckford returned to California.

Beckford, second from left, and three dancers in Haitian dress, 1956, Ruth Beckford Papers, AAMLO

Energized by her experience in New York, Beckford opened her own studios of African Haitian dance—one in Oakland and the other in the Peters Wright studio in San Francisco—while still directing the Rec program. Drawing on her advanced students, she formed a company based on the Dunham model. She went to Haiti to study voodoo, as Dunham had done, and condensed the ritual all-night dances she saw there. Although her company was active for only eight years, some of its members, like Deborah Vaughan and Naima Lewis, went on to distinguish themselves as leaders in dance.

Undated photo, Ruth Beckford Papers, AAMLO

“Ruth Beckford was the hub for the serious black dancer,” Osumare wrote, “and those white dancers who felt the call of ‘a different drummer,’ ” She called Beckford the “regional transmitter” of Dunham technique on the West Coast.

Her classes, like Dunham’s, were physically demanding. As you can see from this clip of her teaching in 1968, she is talking about Damballa, the snake god, and her spine undulations are extreme. Osumare, who is actually in this video (tall and slim with an Afro), recalls the technical challenges:

Every one of Miss Beckford classes were strenuous, with a meticulous approach to learning the Dunham technique and Haitian dance, all leading to nothing short of self mastery. The Dunham barre . . . that left one’s thighs screaming, required exact body placement, endurance, flexibility, and musicality.

For Osumare and many in the black cultural district of Oakland, the power of the drums drew them in:

The most revolutionary aspect of Miss B’s classes, for me, was that drummers accompanied them, not a pianist playing Bach, Beethoven or Mozart. The 6/8 and 4/4 rhythms of Afro-Haitian music were riveting, with the battery of drummers often led by Bay Area drummer Butch Haynes. These rhythms began to open an inner cultural ear that I didn’t even know existed. After the dance barre warm-up, we had center-floor isolations — learning to separate the head, shoulders, rib cage, and hips from each other in order to play the drums’ polyrhythms in the body. Never before had I been expected to be so masterful with my center torso. Sure, I had learned to lock my spine in exact placement for ballet, contract it from the pelvis for Graham, and relax it from the waist for Limon swings. But to carry two or three rhythms in the torso at once was definitely a different cultural experience.

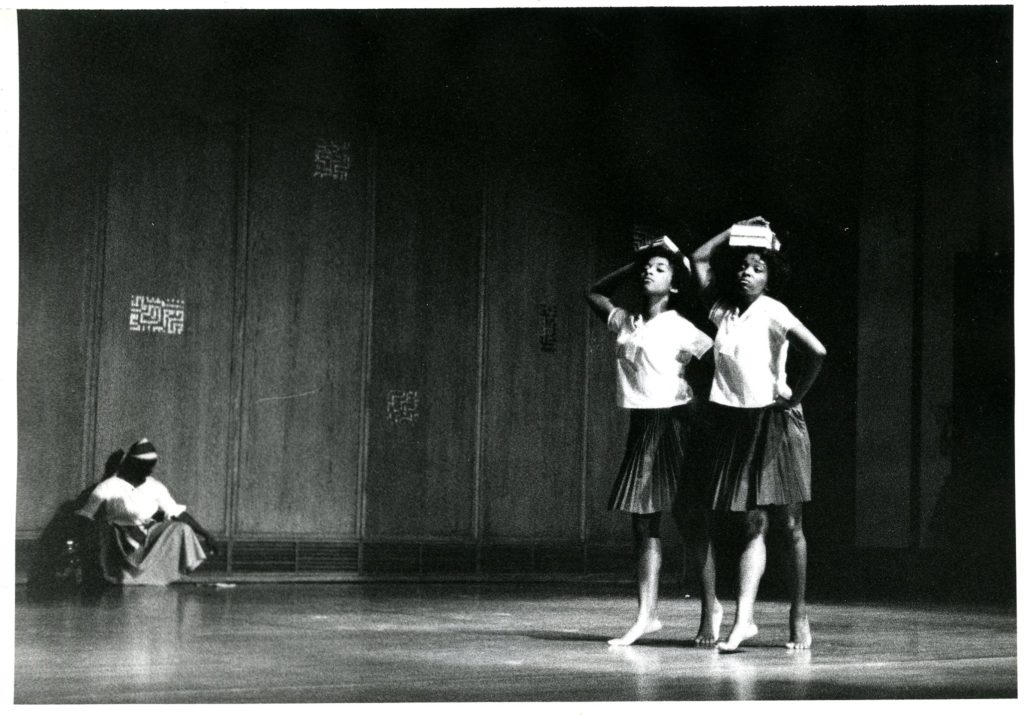

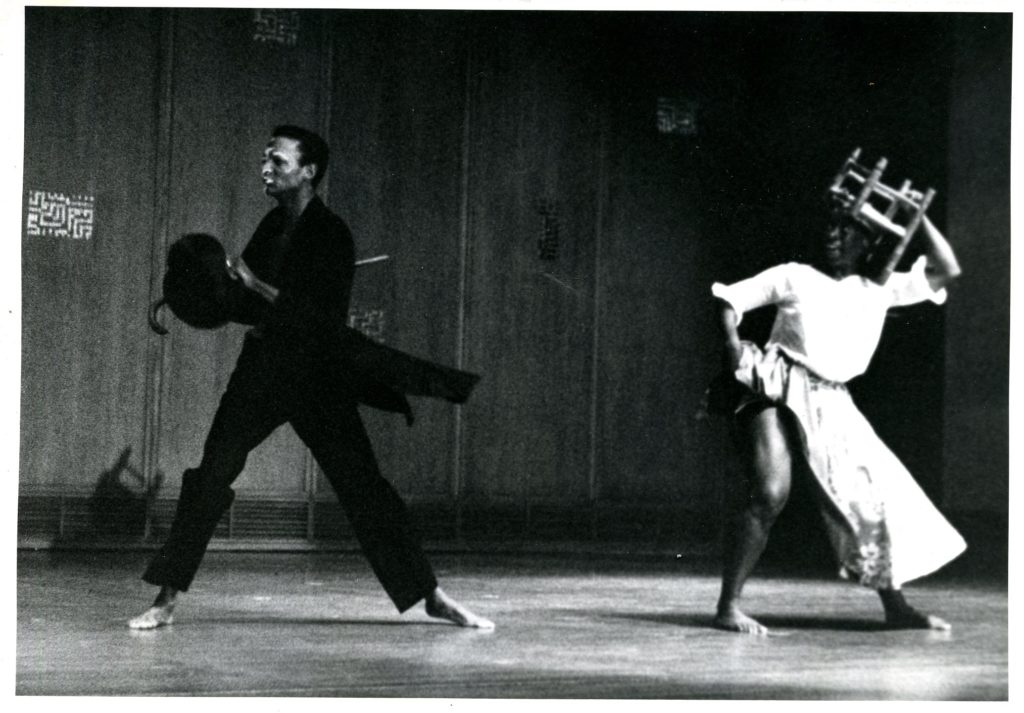

UC Berkeley, 1961, Ruth Beckford Papers, AAMLO

Perhaps because of her vaudeville days as an entertainer, Beckford preferred to tour the college and university circuit. “I had done a great amount of research on our dances, and I thought it would be wasted if it was not in colleges or theater houses where people were accustomed to come and see serious performing. I could’ve gone to Vegas and put on a tassel and made a fortune.”

Beckford at right, undated photo, Ruth Beckford papers, AAMLO

(As an aside, I will add that in one of Beckford’s short bios for program notes, she mentioned that in 1958 she toured with Ruth St. Denis in her Religious Dances.)

Beckford also taught at Mills College, where Trisha Brown and Elendar Barnes, co-founder with Vaughan of Dimensions Dance Theater, were among her students. This video shows her leading a large class at Mills with three drummers in 1974.

Community involvement

In 1968, Bobby Seale, co-founder of the Black Panther Party, enlisted Beckford’s help to start the Free Breakfasts for Children program. Its first location was St. Augustine’s Episcopal Church, where Beckford was a member. (Although she was christened there, she has said that her spiritual practice was more about reading Daily Word at home.) She consulted a nutritionist, helped procure food from local businesses (“Every morning at 6:00 I’d go with my begging bowl and get stuff donated”), recruited parents, and set standards of behavior for the volunteers. Not to mention that she brought in her students to help serve. Vaughan, a teenager at the time, remembers, “She invited us to participate, saying, ‘This is something you all need to know about and be involved in because this is what’s happening in the community.’ So some of us went along to help serve breakfast to kids in the community that didn’t have enough food.”

Beckford knew the program was a success when the first school principal reported the children had become alert and focused. The program grew from a handful of kids at St. Augustine’s to hundreds, then thousands, and quickly expanded to cities across the country. The free breakfasts became a model for the Panthers’ other programs like free health clinics and community ambulances.

(At the time, the Black Panthers were reviled in the white press, which portrayed them as violent radicals. But the aspect of the Panthers that was most threatening to the FBI was the free food program because it was obviously successful. It posed such a national “threat” that the FBI director, J. Edgar Hoover, ordered it to be destroyed by whatever means necessary. A few years later, the government took a page from the Panthers’ playbook and expanded its own program to provide free food.)

Beckford gave unstintingly to her community in many other ways as well. She helped found the Oakland Dance Association as well as the Cultural Ethnic Affairs Guild. She founded the oral history program at the African American Museum and Library of Oakland, interviewing older black people in the work force. She helped the homeless and gave talks in women’s prisons. (“I tell them, ‘You are special’ because I felt those women did not come from loving homes.”) She worked with victims of the 1989 earthquake and counseled people in job training. In 1997, she created her own awards, the Ruth Beckford Award to Extraordinary People in the Field of Dance. As Vaughan told me, “Whatever she thought, she put into action.”

Life after dance

In 1974 Dunham sent Beckford a letter asking her to write her life story. Beckford’s response: “No, no, no. Let me get my sister friend Maya Angelou to write your book.” But Dunham insisted. Even though Beckford had never written a book, Dunham wanted someone who knew and understood her work to take on this task. (“After the initial shock, I understood the degree of her trust in our friendship. My pride began to swell.”) Beckford ultimately agreed, and she enjoyed spending time with Miss Dunham in East St. Louis and in Haiti interviewing her. Many books about or by Dunham have been written since then, but Katherine Dunham, A Biography, is the first authorized biography. Beckford knew her subject well enough to have a little fun with it. In a chapter titled “True, False and Other Myths,” she asks intimate questions like, Do you ever drink before a performance? And Is it true that you were intimately associated with Haitian presidents?

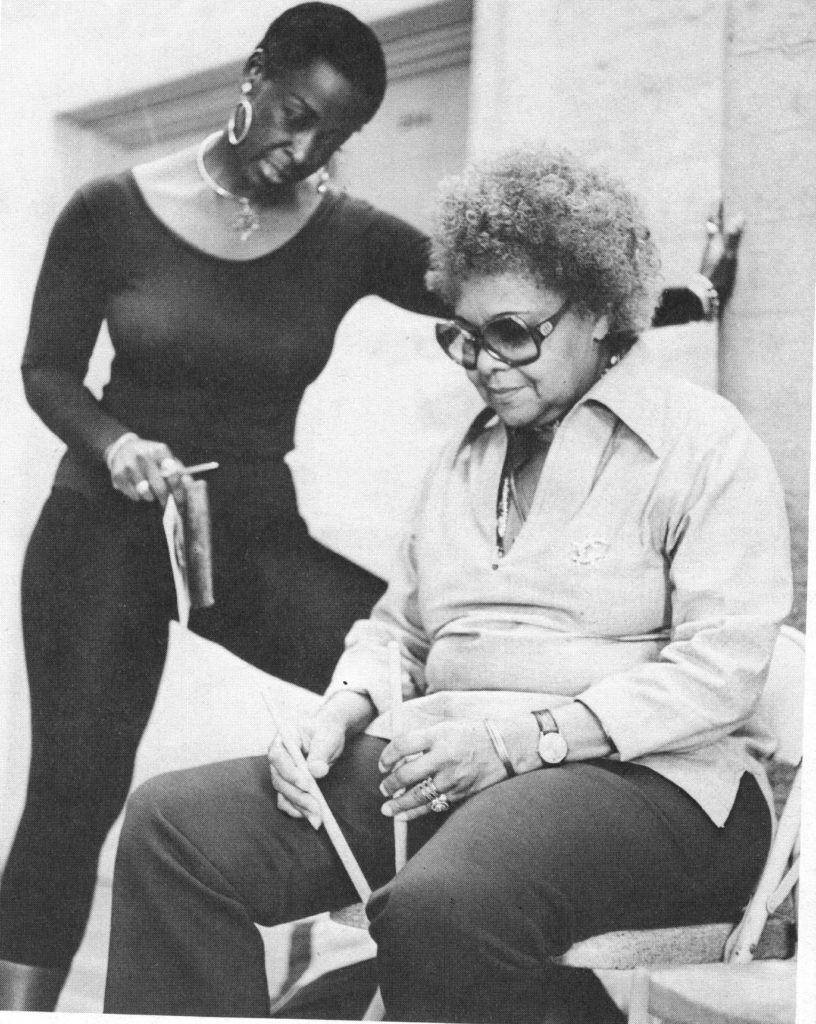

Dunham as a guest teacher at UC Berkeley, assisted by Beckford, 1976, photo Francine Jamison

After publishing her first book, Beckford wrote, starred in, and produced a three-part play, “Tis the Morning of my Life,” about an older woman’s relationship with a younger man, presented by the Oakland Ensemble Theatre Company. Her book Still Groovin’: Affirmations for Women in the Second Half of Life offers spiritual and practical advice for older women. She also wrote two cookbooks and co-wrote The Picture Man, about Bay Area photographer E.F. Joseph.

In addition to her writing life, she appeared in several movies, including My Funny Valentine with Alfre Woodard and Loretta Divine, and two PBS films directed by Maya Angelou.

Beckford in later life, wearing stained glass earrings she made herself

At the opening of “The Ruth Beckford Museum” at Geoffrey’s Inner Circle in 2018, she said, “I choreographed my life. Step by step, year by year.” Sounds very orderly. But there was another part of her personality too:

I’m a risk taker: If it don’t work, it’s OK. I say you should never die and not having done your secret ambition. If you have to go sneak off into the mountains and do it, accomplish your secret ambition.

Hers was to be a lounge singer. She took up voice lessons at a community college and, well past her retirement from dancing, sang as part of the class recital at the end of the semester. Her song was “Nobody Loves You When You’re Down and Out” and she had a ball doing it.

She was bursting with energy till the end. Perhaps Vaughan said it best: “Miss Beckford rode life until the wheels came off.”

Legacy

Although Beckford moved away from dance in her later life, her influence has been continually felt. Vaughan has said, “Miss Beckford broke the ceiling for black dance artists in the Bay Area.” Osumare points out that the profusion of African diaspora groups included local groups like Vaughan’s own group, Dimensions Dance Theater (the oldest oldest African American dance company on the West Coast), and Nontzisi Cayou and her Wajumbe Performance Ensemble. as well as performers emigrating from Ghana (C. K. Ladzekpo), Congo (Malonga Casquelourd), and Senegal (Zak Diouf and the Diamano Coura West African Dance Company).

In 2014, a visual tribute to Beckford appeared as a part of the famous Alice Street mural, titled “Universal Language,” in which she was featured as a towering joy-spreading figure.

Alice Street mural with Beckford as the central figure

But after a battle with gentrification, that mural was obscured. In a compromise solution, a new mural, called “AscenDance,” rose up last summer during Covid. Although Beckford is no longer as large and central a figure as she was in the first mural, she is visible off to the left, still wearing her signature white Haitian dress.

When the late Congolese dancer Malonga Casquelourd was presented with the Ruth Beckford Award in 1997, he spoke for many: “She made the ground fertile for us to land here!”

For all these reasons, last year the African American Museum & Library at Oakland of Oakland Public Library mounted an exhibit called “Ruth Beckford: Visionary Woman,” which has supplied many of the photos here.

¶¶¶

Special thanks to Deborah Vaughan, Dr. Naima Lewis, Dr. Halifu Osumare, Denise Pate, Tamara Sparkles and the Izzies team; Joyce Gordon and Eric Murphy of the Joyce Gordon Gallery; Sean Dickerson, archivist at the African American Museum & Library at Oakland, Oakland Public Library; Risa Jaroslow, Ann Murphy, Joanna Harris, and Liam O’Donoghue.

Other Sources

Library collection

Finding AID for Ruth Beckford Papers at Online Archive of California

Books

Katherine Dunham: A Biography

By Ruth Beckford

Dancing in Blackness: A Memoir

By Halifu Osumare

Beyond Isadora: Bay Area Dancing, 1915-1965

By Joanna Gewertz Harris

Anna Halprin: Experience as Dance

By Janice Ross

Hot Feet and Social Change: African Dance and Diaspora Communities

Eds. Kariamu Welsh, Esailama G. A. Diouf, and Yvonne Daniel

Articles

“Dimensions Dance Theater: For Decades Strong”

By Latanya Tigner

“Obituary: Ruth Beckford, legendary dancer, choreographer”

By Brenda Payton, East Bay Times, May 9, 2019

“Forthcoming Documentary Fights Cultural Erasure in Oakland”

By Arielle Swedback

June 16, 2016

“How the Black Panthers’ Breakfast Program Both Inspired and Threatened the Government”

By Erin Blakemore

Feb. 6, 2018

“Ruth Beckford, 93”

By Brenda Payton Jones

May 10, 2019

“From Guns to Butter: Ruth Beckford-Smith”

By Joshua Bloom and Martin E. Waldo

March 18, 2017

Video interviews

Interview for African American Museum & Library at Oakland, Oakland Public Library

2007

Audio interviews

“I enjoyed every day”: A Tribute to Ruth Beckford

East Bay Yesterday

2019

“Going for Happiness: An Oral History with Ruth Beckford” LEGACY Oral History Program, with Penny Peak, interviewer; Jeff Friedman and Penny Peak, co-editors. San Francisco Museum of Performance & Design, 1995.

Films of dance classes

African/Haitian Dance with Ruth Beckford, 1968, available for viewing in the Archive Collection at Medgar Evers College

Black dance in action, Ruth Beckford workshop at Mills College,1974 (African American Museum & Library at Oakland, Ruth Beckford Papers

Unsung Heroes of Dance History 6

Wendy Perron,

You continually inspire, creating space for that which is good and life enhancing in our universe. This story is beautifully organized, written and researched. It reveals, for me, the innovator and champion that Ms. Beckford was for so many people.

Ayibobo! Ashé! Peace and Blessings!

Hi Wendy,

A wonderful writing on Ruth Beckford.

You may be interested to know that LEGACY Oral History Program recorded a full life-history with Ruth and this oral history research document (recordings/transcripts, etc.) would fit well in your list of references. It is also held at the AAMLO holdings as well as the San Francisco Museum of Performing & Design. The proper reference would be:

Ruth Beckford, with Penny Peak, interviewer, and Jeff Friedman and Penny Peak, co-editors. “Going for Happiness: An Oral History with Ruth Beckford” LEGACY Oral History Program, San Francisco Museum of Performance & Design, 1995.

Thank you so much! I can’t believe I missed this resource. I just added it to my list of resources. If I ever make a book of this series of the Unsung Heroes of Dance History, I will listen carefully to this interview. Just from hearing a tiny slice of this, I can tell that the interviewer is more informed than the other long interview I watched.

Hi Wendy,

Glad to hear our oral history was useful! You may find additional unsung heroes and heroines of dance in LEGACY’s collection. As you know, the West coast is seen and experienced differently from East coast dance and many intrepid lives in dance have evolved in the San Francisco Bay Area, such as Ruth’s enormous contribution, with little recognition outside their Bay Area spheres of influence. Jane Brown would be one I can recommend, as a strong proponent of social justice in dance, among many others.

And thank you for your thoughtful review of Jewishness and Dance; your work on this is much appreciated. Since Rutgers University brought 6 years of Israeli dance artists as guests to our Department, and established an ongoing Study Abroad program in Jerusalem, faculty and students have experienced a powerful slice of the vast array of dance you describe. We now have a fully online course on dance in Israel in our theory curriculum as a result. And thank you for including my friend Yehuda’s work; we had several phone calls and email exchanges working through his Frieburg experiences, resulting in his powerful essay you described so well.

sincerely,

Jeff Friedman

I was just telling someone about Ruth and came upon your article. I knew Ruth well the last 10 years of her life. I was a nurse and she told me when we first met how much she admired me. I have a large integrated crew of left wing friends. She delighted when we would show up at events at Geoffreys Inner Circle. I physically helped set up her museum. Sadly I also spent time at her apartment the last few years. The years of dancing took its toll on her joints. Great Woman.

Heather, how wonderful that you knew her during those years. I’m sure she appreciated your companionship and your help! Thanks for writing.