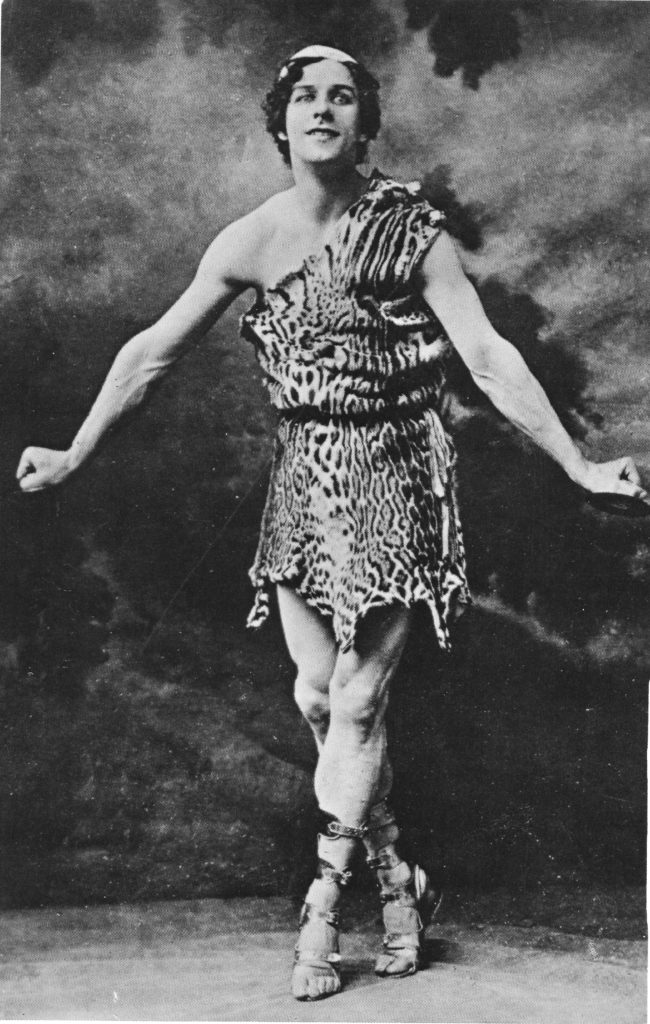

Mordkin in his Bacchanale, collection of Val Golovitser

The name has disappeared from view, but it was Mikhail Mordkin who was the lead dancer in Diaghilev’s first season of the Ballets Russes. It was Mordkin whose partnership with Anna Pavlova caused a sensation in her 1910 United States debut. And it was Mordkin, twenty-nine years later, whose modest little company morphed into American Ballet Theatre.

Born into a family of musicians, Mordkin was accepted to the Imperial Ballet School of Moscow. While still a student, he was so advanced that he was asked to partner top ballerinas like Ekaterina Geltzer. After graduating in 1899, he went into the professional company immediately as a soloist—a rare distinction accorded Nureyev and Baryshnikov as well. Mordkin was appointed regisseur in 1904 and assistant ballet master the following year.

According to Russian dance historian Elizabeth Souritz,

Mordkin was the romantic hero of the Moscow stage. Of magnificent physique, with a beautiful, refined face and an inspired gaze, he danced in the Bolshoi Theater from 1900 to 1908 . . . . His dancing was passionate and powerful, and his poses and gesture were expressive. The fusion of dance and pantomime, something not all ballet artists can achieve, was his specialty. (Souritz 79)

Because of these qualities, Mordkin embodied the newly emotional male characterizations of Alexander Gorsky, the Bolshoi Ballet director who was influenced by both Stanislavsky and Isadora Duncan. Gorsky updated the Bolshoi classics by making them more dramatic and less reliant on symmetrical patterns. As a premier danseur, Mordkin originated the lead male roles in Gorsky’s productions of Raymonda, Swan Lake, La Bayadère, and Giselle.

During the Bolshoi’s first trip abroad, at the invitation of Kaiser Wilhelm to Berlin in 1908—predating Diaghilev’s big splash in Paris by a year—Mordkin served as both premier danseur and ballet master.

The Russian dancer/choreographer Fyodor Lopukhov wrote that Mordkin had “a striking dramatic gift . . . .Like no one else, he was able to fill the huge Bolshoi stage with movements as powerful as a Greek god’s, arousing a storm of applause.” He goes on to say he felt that Diaghilev’s promotion of Nijinsky in Paris robbed Mordkin of the superstar status he deserved.

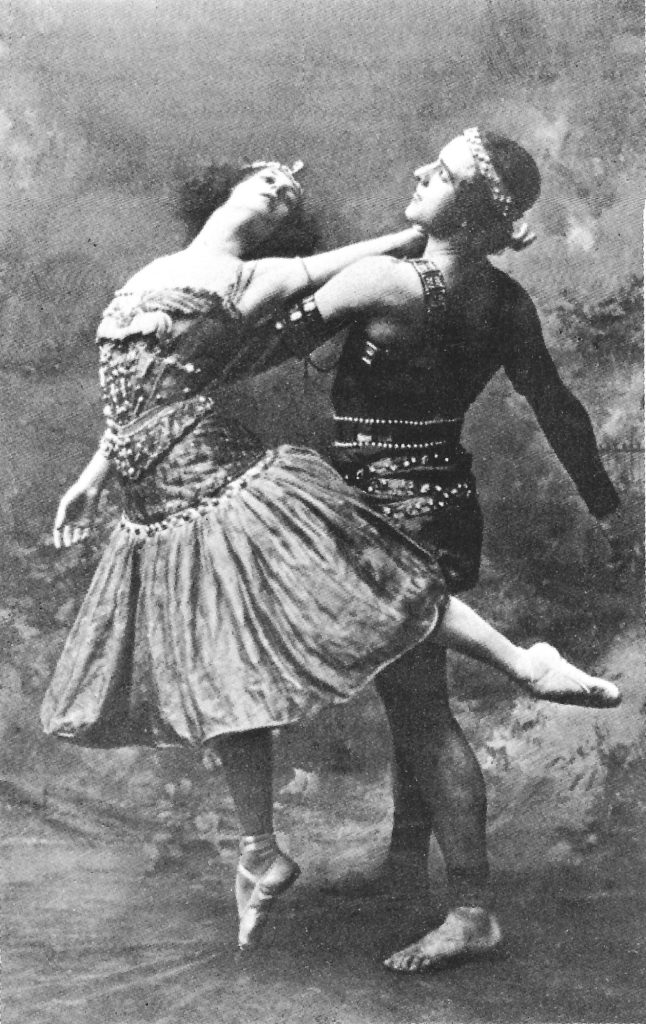

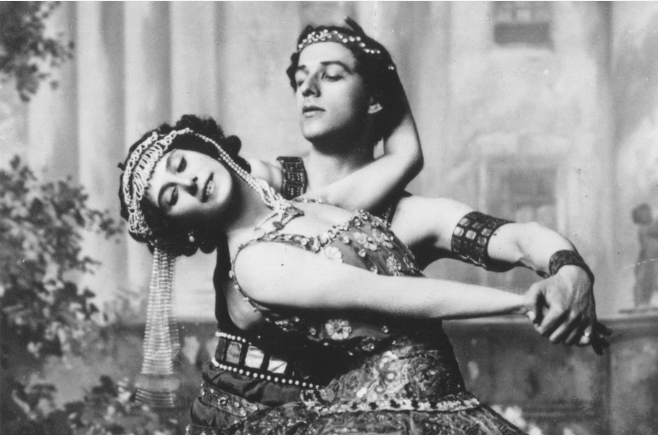

Le Pavillon d’Armide by Fokine, the opening ballet of Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes in Paris, 1909, dress rehearsal with Mordkin and Vera Karalli

Partnership with Pavlova

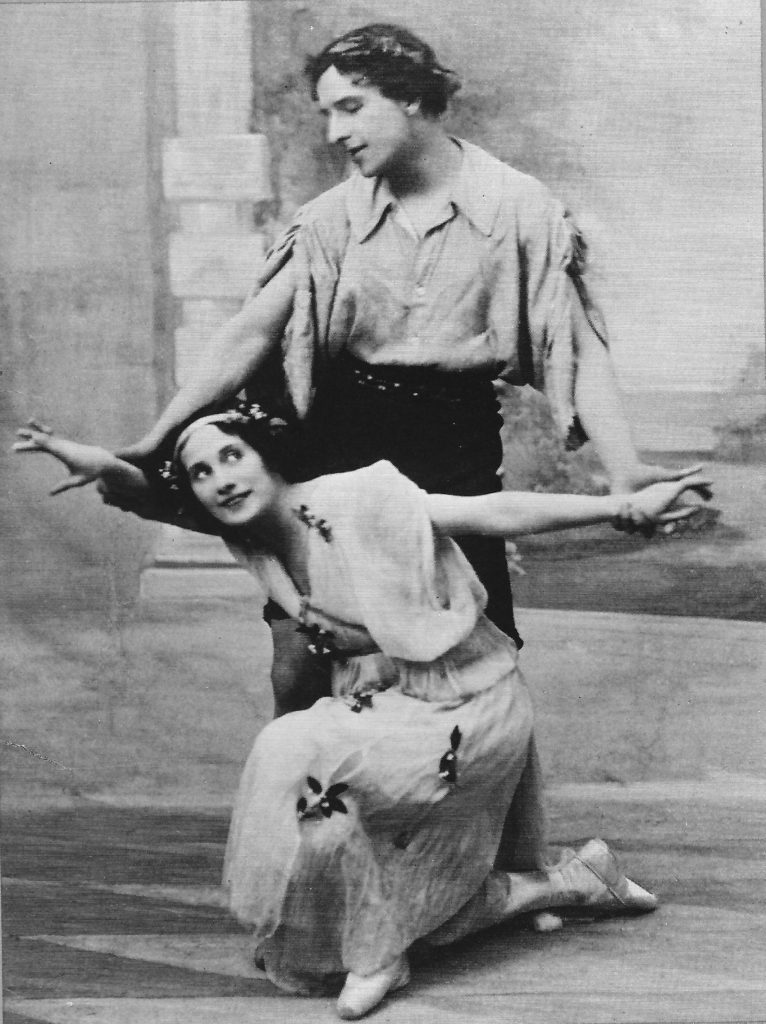

The first time Mordkin danced with Pavlova was for a special occasion in 1906 for which Pavlova was invited from St. Petersburg to join him in The Pharaoh’s Daughter. They had both just reached the highest rank, she with the Maryinsky and he with the Bolshoi.

Pavlova and Mordkin in Pharaoh’s Daughter, c. 1906, Astor, Tilden and Lenox Fndns

Three years later they performed starring roles in Diaghilev’s inaugural season of the Ballets Russes at the Théâtre du Châtelet, but they did not dance together. After the season was over, however, on July 25, 1909, they performed a duet at a benefit for earthquake victims at the Grand Opera. It was probably their version of Michel Fokine’s Bacchanale, which was described by Pavlova’s biographer, Keith Money, as “a torrid chase [that] ended with Pavlova falling to the ground in a state of ecstatic exhaustion.”

Going into greater detail, Money wrote:

The two ran on stage under a veil and, amid much rushing about, occasionally froze in sensual poses during an adagio section. . . . [They] ducked and twisted with almost animal vigor, and even went into kissing clinches. Mordkin was wildly extroverted and untrammeled, and his sheer physicality brought out the vamp in Pavlova. Together they struck gold.

Pavlova and Mordkin in Valse Caprice

Otto Kahn, chairman of the board of the Metropolitan Opera House, was in the audience that night and was as swept away as everyone else. He invited the two stars to come to New York and perform at the Met the following year. When they arrived, since they were unknown in New York, they were given a late-night slot after a four-act opera. Even so, they stunned the audience with a two-act Coppélia, and their bows lasted till 1:00 in the morning.

As part of that tour, they brought their Bacchanale to the Brooklyn Academy of Music, this time after Puccini’s Madame Butterfly. Reading an article in the local Brooklyn Citizen, one gets the picture of what a male ballet dancer was up against:

Michel Mordkine [sic] is the only male dancer who has been able to overcome a certain . . . repugnance in America to male ballet dancers . . . . A Bacchanale dance in the end brought their performance to a whirlwind finish amid thunders of applause.

Since critics in the U. S. and the U. K. had not yet seen Nijinsky, Mordkin was, according to Jane Pritchard, “acclaimed as the greatest male dancer of his time.”

It was said Pavlova and Mordkin were in love with each other, but the budding romance ended suddenly. Both tempestuous, they each had an episode of walking out on each other, she in San Francisco, and he a year later in London. Jealousies brewed as one or the other received more glowing press attention. Once at a performance at the Palace Theatre in London, as the curtain descended, Pavlova slapped Mordkin.

Mordkin and Pavlova in Bacchanale

“Everybody is talking about the quarrel,” reported The Tatler, “which prevents these two artists dancing together in those pieces which were the sensational joy of the last London season.” Keith Money believed it had to do with a partnering mishap that they blamed on each other. Another theory was that she was angry that he received more applause.

Dance writer Jennifer Dunning names the 1910 season at the Met as the beginning of America’s love affair with Russian Ballet. Although Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes had astonished Paris in 1909, that splendid company did not arrive on these shores until 1916.

Although Pavlova generally got better notices, Mordkin was also favored in the American press. The New York Telegraph wrote, “While Mme. Pavlova, whose fame preceded her appearance in New York by many months, quite fulfilled expectations, it was Mordkin who took us entirely by storm and created by far the greater sensation.” Dorothy Barrett, describing him in Dance Magazine years later, wrote, “Neither prince nor pirate, he had the appeal of both. Handsome, with a physique that Tarzan might envy, his masculinity belied the flowers in his hair.” (You can see in the costume at the top, the Tarzan effect.)

Mordkin’s popular Bow and Arrow dance, according to Money, “broke through the audience’s reserve.” Yet a critic writing in The Telegraph mocked him for appearing with bare legs painted brown.

Pavlova and Mordkin in Valse Caprice 1912, Dance Collection

Another source of mockery was their two-act Giselle, deemed an “uphill battle” by one syndicated columnist. However, the performers shone through, according to a critic who wrote, “Giselle . . . which began the program, is a weariness in the flesh. Yet, over all these obstacles, the art of the two dancers triumphed.”

Their combativeness continued through two long tours that criss-crossed the United States from 1910 to 1912. By the end of that time, both Pavlova and Mordkin chose new partners. According to Gennady Smakov, Pavlova often regretted the break with Mordkin and later advised the male dancers in her company to emulate his dramatic abandon.

Pavlova and Mordin in Russian Dance, 1910, collection of Cyril Beaumont, V & A Museum

Mordkin’s acting ability created excitement, but sometimes he went too far. As Conrad in Le Corsaire, he would suddenly scream. The critic Akim Volynsky, quoted by Smakov, found his “outbursts of temperament and frenzied enthusiasm hardly appropriate in the frame of traditional presentation.”

Return to Russia

In 1912 Mordkin returned to Moscow and resumed dancing as a Bolshoi principal for the next six years. He toured throughout Russia with a group he called All-Star Russian Imperial Ballet, which included his new wife, Bronislava Pojitskaya, a fellow dancer from the Imperial School. Because of his ability to express emotion through movement, he also became involved with the experimental Kamerny Theatre of Moscow, leading to an invitation from Konsantin Stanislavsky to teach students at Moscow Art Theatre in “plastique” and rhythmics. (Stanislavsky’s pioneering approach, known as method acting, was an influence on the Bolshoi as well as on Lee Strasberg and his Actors Studio in New York.)

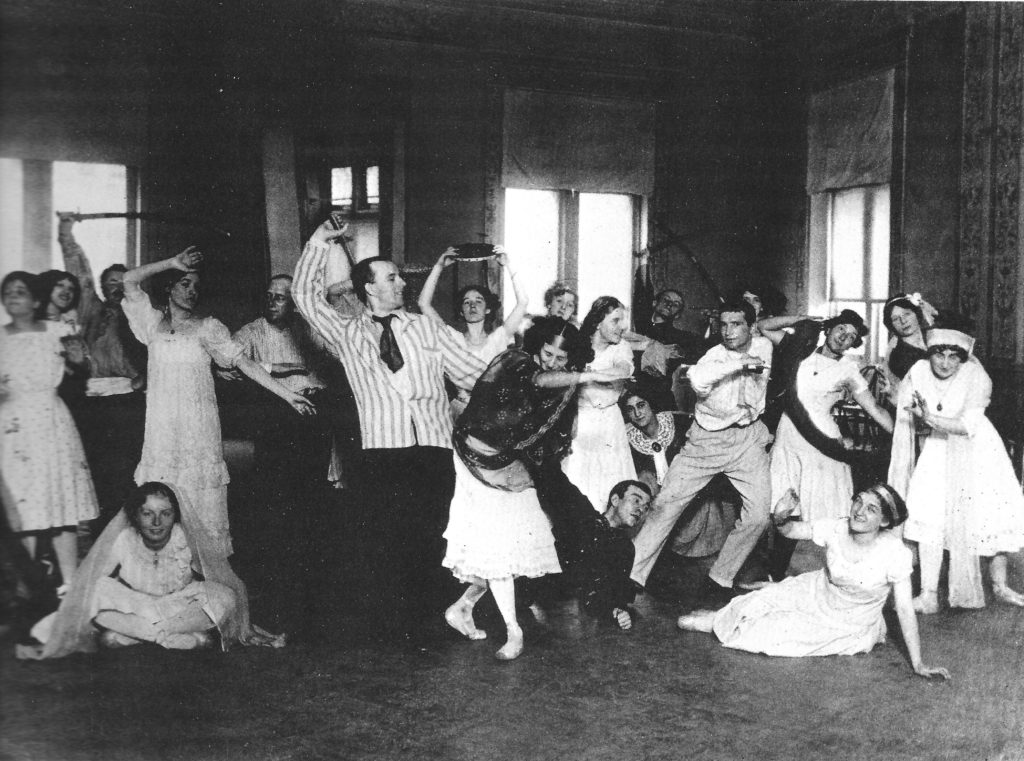

Exempted from military service during World War I, Mordkin had to entertain the troops in addition to his other touring commitments. After the outbreak of the October Revolution in 1917, he choreographed his first large group piece. This was The Legend of Aziade, created under the influence of the popular Orientalism of the Fokine/Bakst Schéhérazade (1910). The following year he staged this work for the Nikitin Circus, pulling out all the stops. The cast included soloists from the Bolshoi as well as about 200 supers. Performers broke the fourth wall and danced into the house. Colored lights were projected onto some scenes, and horses trotted onstage in another scene. The audience ate it up. According to Souritz, so did Anatole Lunacharsky, the Soviet Culture minister who also championed Isadora Duncan.

Mordkin and Pavlova rehearsing Aziade in New York, 1910

In the fall of 1918 Mordkin went to Kiev, which had a thriving theater scene at that time. While staging Giselle and other classic ballets at the Kiev City Theater, he opened a studio that offered ballet, gymnastics, and social dances as well as classes in “expressive” movement, or “plastique.”

In an essay on the period, Lynn Garafola quotes a young acting student, Stepan Bondarchuk, about Mordkin’s lessons in Kiev:

Work with Mikhail Mordkin inspired us with its originality, temperament and grand sense of plastic form. The exercises were not the standard classical ones we knew . . . Rather you could call them creative études. Mordkin would ‘sing’ with his beautiful body to music, and we would try to do the same. (qted in Garafola, Dance Research Journal, 2011, 147)

He also had a school in Tblisi, and one of his projects there was an attempt at his own version of Fokine’s Les Sylphides. He seemed to be always remaking what had already been made.

In 1922 Mordkin returned to the Bolshoi as ballet master. With the school now under Communist rule, conflicts immediately arose and he felt it impossible to work there. He left after twelve days. He and his wife and small son traveled to the Caucasus and fell victim to a triple devastation: the typhus epidemic, the Russian Civil War and the ensuing famine. According to one account, the family was found on the edge of starvation in an abandoned boxcar by the American Near East Relief Committee. This experience made Mordkin more determined than ever to leave Russia.

New York

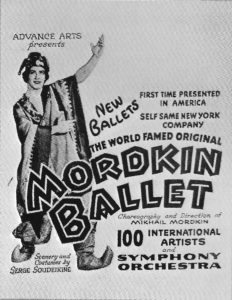

Poster for the Mordkin Ballet, 1920s

The ballet master accepted an invitation from producer/agent Morris Gest to come to New York in 1924. Gest booked him into the Greenwich Village Follies at the Winter Garden (right around the same time Martha Graham was in the Follies, where she worked with Michio Ito). For much of the 1926–27 season, Mordkin was on the road with a group he called the Mordkin Ballet. These dancers were mostly his students plus Vera Nemchinova, Pierre Vladimiroff, and Felia Doubrovska, all formerly with the Ballets Russes. He also taught at the Stanislavsky hub in midtown known as American Laboratory Theatre. There were times when he took a gig in Vaudeville that paid well  but was less than artistically fulfilling.

but was less than artistically fulfilling.

An interesting cultural exchange was taking place that brought out Mordkin’s wicked sense of humor. While the American Isadora Duncan was performing in the Soviet Union, embracing the Communist ideal and proclaiming she would teach the Soviet children to dance, Mordkin was clearly preferring America, where he was paid better. According to Charles Payne (1929–1983), a longtime administrator of American Ballet Theatre, Duncan had “denounced Mordkin for deserting the Soviets.” To which Mordkin responded, “Miss Duncan cannot dance. That is why she has become a politician.” (This comment was no doubt because Duncan often gave speeches after her concerts.)

In 1927 Mordkin opened his Studio of Dance Arts in Carnegie Hall. One of his students was Lucia Chase (1907–1986), a young widow who had initially wanted to be an actress. The recent death of her husband had plunged her into an abyss of grief that separated her from society. Attending Mordkin’s daily ballet class was her way of gradually coming back into the world. She appreciated the consistency, the rigor, and his emphasis on drama over technique (she had started lessons too late to develop strong technique anyway). And he noticed that she shone onstage in character roles. Chase, who had inherited a fortune, let him know she would help him develop a company. For starters, she offered him studio space at her summer home in Narragansett, Rhode Island, where the second floor of the stable was empty.

Chase’s biographer and son, Alex C. Ewing, described Mordkin from his mother’s point of view:

Mordkin was an exceptionally powerful figure, both physically and temperamentally, who combined a domineering personality with a colossal ego. . . With his proud bearing, his muscularity, his sudden unpredictable outbursts, he was like a magnificent animal that had to be accepted on his own terms. (Ewing, 28-29 and 30)

In 1936, Mordkin produced a semi-professional, small-scale Sleeping Beauty at the Woman’s Club of Waterbury, Connecticut, Chase’s hometown. Chase was Aurora; Dimitri Romanoff, a dancer from Russia, was Siegfried; and Viola Essen, a teenage prodigy, danced the Bluebird as a solo. In publicity, Mordkin called Chase “The All-American Prima Ballerina.” He knew where his bread was buttered.

Lucia Chase with Dimitri Romanoff in Mordkin’s Sleeping Beauty, 1937, photo Delar

The next engagement, four months later at the Majestic Theater, included Mordkin’s Voices of Spring and The Goldfish (based on Gorsky’s ballet of the same name), as well as Giselle. The New York Times critic John Martin praised his performance as the old fisherman in The Goldfish, but barely mentioned Giselle, saying only, “Lucia Chase is by no means an ideal Giselle.”

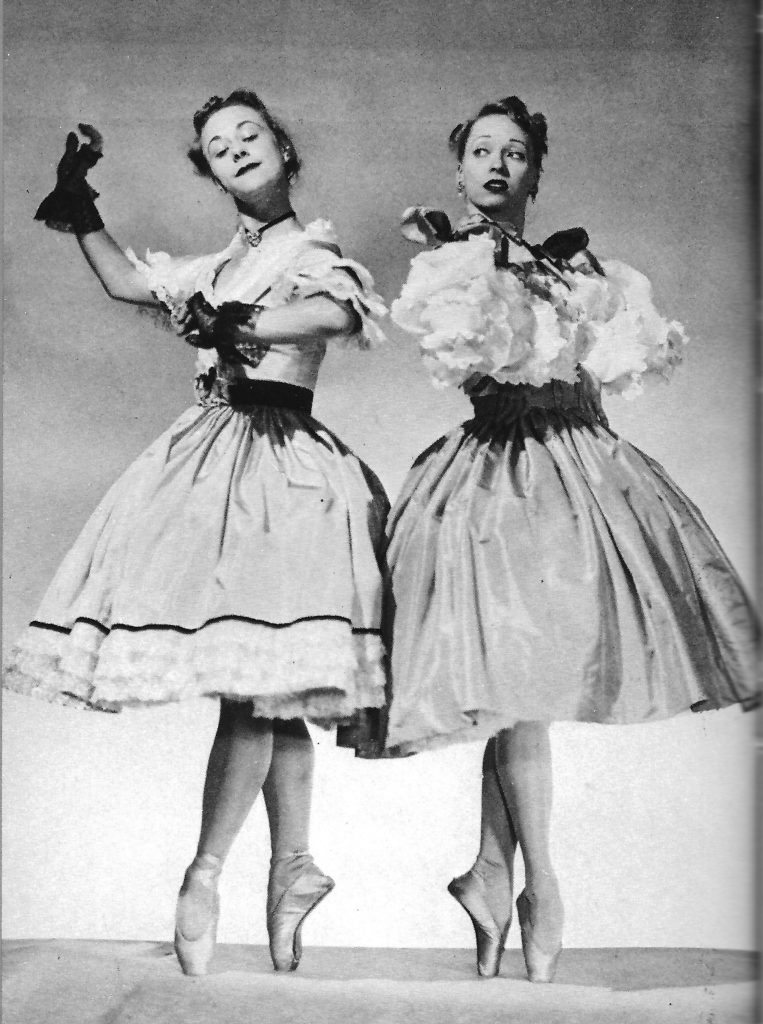

Chase knew she wasn’t up to these starring roles and insisted they engage real ballerinas. The new managing director, Rudolf Orthwine, agreed. German emigré Rudolf Orthwine (1893–1970) had met Mordkin in 1935 and helped him set up the Mordkin Ballet. Together they set up Advanced Art Ballets, Inc. with Orthwine as managing director, Mordkin’s son Michael Jr. as business manager, Mordkin père as choreographer and director, and Lucia Chase as principal backer. (Orthwine soon became a publisher when he bought two dance publications and merged them in 1942 to become Dance Magazine.) They brought in Patricia Bowman, a Fokine protégée who became prima ballerina of Radio City Music Hall; Karen Conrad and Edward Caton, who’d been with the Philadelphia Ballet (previously the Littlefield Ballet); and Nina Stroganova and Vladimir Dokoudovsky from the Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo. The company became more professional, but all the choreography was still Mordkin’s.

Rehearsing Voices of Spring, from left: Stroganova, Mordkin, Bowman, Chase, and Conrad, ABT Archives.

Enter Richard Pleasant, Architect of ABT

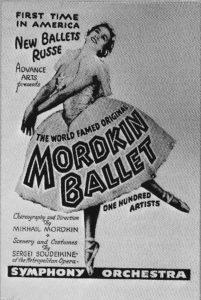

Richard Pleasant, Dance Magazine

Because Mordkin was on tour a lot, Orthwine decided they needed someone to manage his New York studios. Dimitri Romanoff told them about a smart young man he’d met in California when he was dancing in San Francisco Opera’s production of Le Coq d’Or. (This version of Le Coq d’Or, originally by Fokine, was choreographed by Adolph Bolm, who’d danced in the troupes of both Pavlova and Diaghilev.) Richard Pleasant had been a supernumerary in that show. With a degree in architecture from Princeton—which got him nowhere during the Great Depression—he’d had a string of jobs and was looking for something more permanent. He came to Chicago to see a Mordkin performance, and Romanoff introduced him to Chase and Orthwine.

Pleasant seemed to be capable in a general way, but he was a bit more dance-savvy than he first appeared: He had spent summers at the Perry-Mansfield School of Theatre and Dance in Colorado, had studied with the legendary Carmelita Maracci, and had encountered Agnes de Mille in Hollywood. In fact, according to B. F. Giannini, de Mille “was amazed when this lanky twenty-six-year-old from Colorado announced that someday he would have a ballet company of his own.” Orthwine hired Pleasant for $260 a month to manage the studios, of which here were five at that time. (Reynolds 273)

Although his job description did not include any kind of artistic advisement, Dick Pleasant (1909–1961) could see that Mordkin’s touring enterprise was not top-notch. He started dreaming of a company of American dancers with a repertoire of the best international choreographers. Maybe it would be the Mordkin company, but expanded to include multiple choreographers. Or maybe it would be a consortium of companies, each led by a different choreographer. Pleasant’s ideas were evolving.

In the summer of 1939, Pleasant spent two days in Narragansett convincing Chase of his larger picture. He pointed out that if they had a more expansive and professional operation, it would be more likely to attract other backers. Once she gave him the green light, he called Carmelita Maracci and Ruth Page and tried to involve Mordkin as one of the group of choreographers.

Mordkin would have none of it. For one thing, he felt disdain for American choreographers working in classical ballet. For another, bigger reason, he was wary of anyone trying to take over his company. He knew what happened to Fokine, who was twice supplanted as choreographer by Diaghilev’s favorites—first by Nijinsky, and later by Lifar. So Mordkin’s paranoia, combined with his poor command of English, did not help the situation

A World War Opens the Door to Top Choreographers

Meanwhile, Pleasant’s attempts to recruit Fokine, Antony Tudor, and Anton Dolin at first came to naught. They were all too busy. But then, cataclysm: Hitler invaded Poland on September 1, 1939 and war was declared in Europe. All the ballet companies shut down, and many artists wanted to flee Europe. Fokine, Tudor, and Dolin all pivoted to accept Pleasant’s offer. Fokine was considered the best living choreographer at the time—even by Mordkin. So when Fokine came on board, Mordkin saw the writing on the wall. He refused to speak to Pleasant, so communication had to be carried out through Mordkin’s son, Michael Jr. In this indirect manner, Pleasant requested a list of preferred ballets and dancers from Mordkin, but it never came. Although Pleasant had initially promised to include nine Mordkin productions, only one, Voices of Spring, was on the rehearsal schedule. Dolin, who had told Pleasant that Mordkin’s stagings of the classics were not authentic, took over the staging of Swan Lake and Giselle, and Bronislava Nijinska staged La Fille Mal Gardée—all three were ballets that Mordkin had set many times.

The new enterprise, now called Ballet Theatre, opened its inaugural three-week season at the Center Theatre in Rockefeller Center on January 11, 1940. It was under the aegis of Advance Arts Ballets, the legal entity created by Orthwine and Mordkin. Orthwine was now president, Pleasant managing director, and Chase still the prime backer and principal dancer. Mordkin’s role was reduced to setting a single ballet.

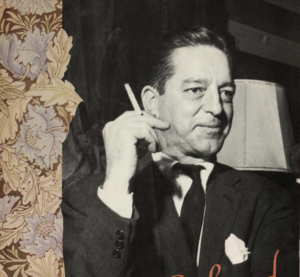

Voices of Spring with Patricia Bowman and Nina Stroganova by Ira Hill

The repertoire was a dazzling array of the latest ballets by international choreographers including Tudor’s Dark Elegies and Judgment of Paris, de Mille’s Fall River Legend and Three Virgins and a Devil, Fokine’s Les Sylphides and Bluebeard, and Eugene Loring’s Great American Goof. Eleven choreographers, twenty-one ballets, fifty-six dancers (plus twelve in José Fernandez’s “Spanish unit” and fourteen in de Mille’s “Negro Unit”), and three conductors. Among the dancers were Chase, Conrad, Romanoff, Stroganova and Dokoudovsky from Mordkin’s company as well as Nora Kaye, Donald Saddler, Alicia and Fernando Alonso, Diana Adams, Antony Tudor, and Hugh Laing. The company soon obtained works by Massine, Balanchine, Robbins, Ashton, and Bolm. Needless to say, Ballet Theatre, renamed American Ballet Theatre in 1957, has become one of the world’s great ballet companies. It couldn’t have happened without Mikhail Mordkin. He had cultivated Chase as a dancer and donor; he had involved Orthwine as chief administrator; he had hired Pleasant, and he had trained some of the dancers.

Mordkin as Ballet Master

From the time he was a teenager at the Imperial School in Moscow, Mordkin was always teaching somewhere. In New York, his notable students included not only Chase and Essen, but also Leon Danielian, Tanaquil Le Clercq, Katherine Hepburn, and Hemsley Winfield (1907–1934), the African American man who started a Black dance company and then died tragically at age 26.

Even after being evicted from his own company, Mordkin remained a popular teacher. He continued to offer daily classes at the Masters Institute on Riverside Drive until he died in 1944.

Mordkin directing rehearsal of Giselle, 1936

Many years after his death, Mordkin was still a vivid presence for many. Julia Vincent Cross reminisced about his classes in the August 1956 issue of Dance Magazine:

I, like many others, was overwhelmed by his vivid personality. At first he almost frightened me by the whirlwind tempo of his classes. Mordkin, with his wonderful feeling for rhythm, sweep and emotion, would sometimes start a movement slowly—then go quicker and quicker—until a climax was reached which would put me into great confusion. When this occurred, as it did on many occasions with all of his students, he would stop the whole class and ask to have a funeral march played.

Mordkin had a tendency to frighten his pupils or make fun of them. But this really grew out of a wonderful sense of humor. And his usual attitude was one of love and affection, especially for those he thought had talent. One of his rare qualities as a teacher was to consider each pupil as an individual and to try to bring out some special personal quality.

He loved his teaching and his pupils with a fervor and devotion which seemed to carry them forward as dancers without a great deal of concentration on form and technique. His lessons always depended on his mood of the moment. He never gave a dull class. He inspired one to move—to flow with the music. Even his barre exercises forced one to use the whole body rhythmically. He was never affected, self-conscious or false. His dancing stemmed from his heart. (Cross, 40 & 52)

After he died, his devoted wife Pojitskaya, who had been ballet mistress to his company, continued teaching at his studio until the late 1960s.

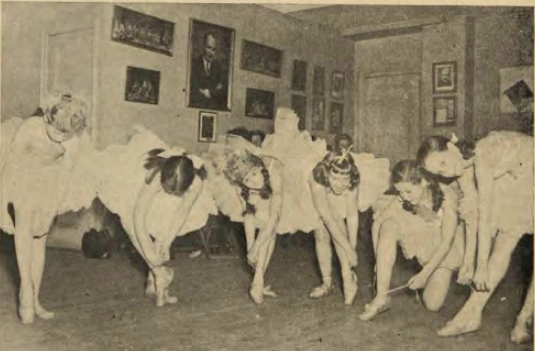

Students at Mordkin Studio preparing for a recital, Dance Magazine, c. 1940s

Legacy

Mordkin was essential in bringing Russian ballet to the U.S. A compelling performer and invigorating teacher, he helped create the mold of the heroic Soviet male dancer at a time when women dominated the ballet stage. And he laid the foundation for ABT.

However, he was never considered a distinguished choreographer. Elizabeth Souritz, has this to say:

Mordkin did not have talent as an expressive choreographer; his subjective biases as an actor prompted him to dramatize dance along the lines of romantic melodrama. Moreover, he imitated Fokine and Gorsky but his works did not contain any new ideas at all. (Souritz 81)

Even Orthwine, who called Mordkin a genius as a dancer and mime, made no claims for him as a choreographer. My guess is that his style became outdated and Pleasant picked up on that. Smakov has written that the early films of his works look like silent movies, and that is borne out in this clip from The Legend of Aziade.

Nevertheless, Mordkin opened up the United States to ballet in ways that aren’t always obvious. The relative prosperity of the U.S. had something to do with it. “Why should we go back to Russia,” he once said, “when we can earn more money here in American in a year than we could earn in Russia in ten years?” As Dorothy Barrett wrote,

When reports reached Russia of the way ballet paid off in this country, the low salaried dancers in the Czar’s ballet grew restless. Nor did Mordkin forget that after eight years as soloist in the Moscow Ballet he had been able to save very little substance. He wrangled leaves for thirty artists from the Imperial Ballet and took them on his American tours. For many years afterwards Russian dancers rushed to this country as to the promised land. (Barrett, Dance Magazine, Sept. 1948, 47)

Perhaps this last word from Barrett explains the secret to Mordkin’s magnetism: “Through it all, he communicated a kind of mad passion for all that Russian ballet stood for.”

¶¶¶

Sources

Books

Bravura! Lucia Chase and the American Ballet Theatre

By Alex C. Ewing

University Press of Florida, 2009

Soviet Choreographers in the 1920s

By Elizabeth Souritz

Duke University Press, 1990

Anna Pavlova: Her Life and Art

By Keith Money

Knopf, 1982, out of print

Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes

By Lynn Garafola

Da Capo Press, 1989

Anna Pavlova: Twentieth Century Ballerina

By Jane Pritchard with Caroline Hamilton

Booth-Clibborn Editions, 2012

Catherine Littlefield: A Life in Dance

By Sharon Skeel

Oxford University Press, 2020

The Great Russian Dancers

By Gennady Smakov

Knopf, 1984, out of print

Bolshoi Confidential: Secrets of the Russian Ballet from the Rule of the Tsars to Today

By Simon Morrison

Liveright, Norton, 2016

But First a School: The First Fifty Years of the School of American Ballet

By Jennifer Dunning

Viking, 1985, out of print

No Fixed Points: Dance in the Twentieth Century

By Nancy Reynolds and Malcolm McCormick

Yale University Press

Articles

“The Era of Mikhail Mordkin” by Charles Payne

American Ballet Theatre

Knopf, 1978, out of print

“Richard Pleasant: An American Dreamer”

By B. F. Giannini

Dance Magazine, Jan. 1990

“Mikhail Mordkin”

By Rudolf Orthwine

Dance Magazine, Feb. 1943

“Mikhail Mordkin: His Last Curtain Call”

By Rudolf Orthwine

Dance Magazine, Sept. 1944

“Mikhail Mordkin: Pioneer in the Ballet Bush Country”

By Dorothy Barrett

Dance Magazine, Sept. 1948

“A Class with Mikhail Mordkin”

Julia Vincent Cross

Dance Magazine, Aug. 1956

“Rudolf Orthwine (1893–1970)”

By William Como

Dance Magazine, Sept. 1970

“An Amazon of the Avant-Garde: Bronislava Nijinska in Revolutionary Russia”

By Lynn Garafola

Dance Research Journal, Winter 2011, Vol. 29, No. 2, pp. 109–166, pub. Edinburgh University Press

“Stanislavski and America: A Critical Chronology”

By Paul Gray

Tulane Drama Review, Winter, 1964, Vol. 9, No. 2, pp. 21–60, pub. The MIT Press

“Mordkin, Mikhail”

The Oxford Dictionary of Dance

“Mordkine and Pavlowa Add Amazing Grace to Opera”

Brooklyn Citizen (no byline), April 5, 1910

http://levyarchive.bam.org/Detail/objects/4669

Via BAM Levy Archive

Films

Lucia Chase Tribute Film, a film by the 2018 Connecticut Women’s Hall of Fame

Excerpt, The Legend of Aziade

With Mordkin and Pavlova, possibly from 1910 at the Metropolitan Opera House or later

Thank you for this wonderful acknowledgment of Mordkin! I’ve written about his NYC teaching in my book (Shapes of American Ballet: Teachers and Training before Balanchine, Oxford University Press, 2016). Here are a couple of fun anecdotes that paint a vivid picture of him in the studio:

Leon Danelian of Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo fame, in an interview with Jocklyn Armstrong, recalled: “One day we couldn’t do the combination and he went down on his hands and knees and prayed to Terpsichore to come down!”

Dorothy Kilgallen wrote about Mordkin’s class in the 1939 Journal American, saying: “With a fine display of strength he beats relentlessly on the floor with a wooden stick to sustain the tempo, shouting a running comment.”

And of course you’ve noted Julia Vincent Cross’ lovely reminiscences of his classes here. An unsung hero indeed. I’m delighted to see him remembered.

Thanks for these great reminiscences. I’ll have to get your book. In 1954, I studied with Tanya Doukodovsky, sister of Vladimir, who danced with Mordkin. She had a stick too.

The clip is from “Aziade,” a silent feature film released in Russia in 1918, directed by Iosif Sojfer, filmed by Alexandre Stanke, and starring Mikhail Mordkin and Margareta Froman. A print of the film was discovered around 1970 and a copy was obtained soon after for the NYPL Dance Collection by Gegi Oswald.

Margareta Froman (1890-1970) was a Bolshoi ballerina and her brother Maximilian Froman (1889-1971) was a Bolshoi soloist. Before and after the October Revolution, they toured with Mordkin’s small company in Russia, Crimea, and Ukraine. They parted ways in 1920, with the Fromans arriving in Zagreb in 1921.

Thank you so much for identifying the woman dancer. Obviously, whoever posted that clip assumed she was Pavlova. (The eye make-up looks the same!) I will consider replacing it with this clip, which does identify her as Froman, but it’s distorted. Which spelling is correct: Maraareta or Mararita?

Her name appears in a variety of forms depending upon the country and translation from Cyrillic into Roman letters, but Margarita Is fine.