Where has American modern dance gone? Has it been subsumed or consumed or bumped off by contemporary dance? Or by contemporary ballet? By hip-hop? Have the earthy heroics of early modern dance become irrelevant? Replaced by the anti-heroes of Judson Dance Theater and later? Has modern dance fled to Europe and looped back to us in conceptual non-dance? Or has it gone to Korea? If modern dance returns in the form of a re-organized troupe of Paul Taylor’s, will anyone go see it?

Barbara Morgan’s famous photo of Graham’s Primitive Mysteries, 1931

These questions have been sparked by my recent viewings of the Limón and Graham companies and by participating in Valentina Kozlova’s quest to discover “contemporary dance” talent. Plus, there was that strange announcement by Paul Taylor saying he will no longer make new dances but will open his company as a home for modern dance.

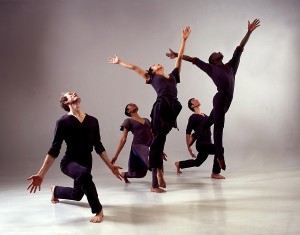

Different kinds of dance speak to us at different times. When Martha Graham and Doris Humphrey broke away from Ruth St. Denis in the 1920s, they were searching for an American form of dance, a form that would replace vaudeville with art and replace decoration with substance. Their pioneering work, inspired by American landscapes and cityscapes, was physically grounded and spiritually uplifting. In modern dance classics like Graham’s Primitive Mysteries and José Limón’s Psalm, the group yields to the suffering and exaltation of the chosen individual.

José Limón’s Psalm, photo by Beatriz Schiller

I used to think that modern dance turned into contemporary dance, that it evolved naturally. (In my own evolution as a dancer, I passed through Graham, Limón, Cunningham, Tharp, and Trisha Brown.) But I see now that the work of Graham and Limón is still very much with us. Modern and contemporary dance co-exist. When their companies perform those early classics, we feel that grounding underneath them. We feel the brave pioneering aspect of it, the insistence on human dignity in the face of adversity—even if we don’t feel it speaks directly to us today. The contraction and release of Graham, and the fall and recovery of Humphrey theatricalized deeply felt human emotion. These visceral approaches, framed by a strong sense of design, formed the foundation of modern dance.

When Cunningham left Martha Graham’s company in the 1940s, he kept the austerity but left the drama behind. He scattered his dancers all over the space, de-centering it, allowing the audience to choose where to look. At the same time he embraced the verticality of ballet rather than the earthiness of modern dance. And he eschewed any kind of overt narrative. His style was so different that it needed a new name, and contemporary dance was born.

Gyeong Jin Lee’s solo Stranger, photo by Yelena Yeva

In recent years, “contemporary” has become a catchall term meaning anything that’s not identifiable as ballet, especially on TV and in competitions. So I was curious when I served as a judge last month in the Valentina Kozlova International Ballet Competition, which this year focused on “contemporary dance” (results are posted here). What we judges found was a whole gamut, from glittery pink ice-skating skirts and pointe shoes to fierce solos that were gripping to watch, in much the same way people reacted to Graham’s early work. Three of these enthralling solos came from Korea.

JuMi Lee’s solo Hailling Sorrow, photo by Yelena Yeva

It turns out that the Korea National University of Arts School of Dance is producing terrific dancer/choreographers who know how to delve inside themselves for material. Their teacher, Jeon Mi-Sook, a fellow judge at VKIBC, told me that the students study ballet, Graham, Limón, and Cunningham at different stages of their training. What struck me was that, like early Graham and Humphrey, their dancing was deeply visceral—to the point where one movement was almost sobbing—contained by very designed shapes. They haven’t yet acquired the irony of today’s American visceral dance makers.

Back to Paul Taylor’s plan of renaming his company Paul Taylor’s American Modern Dance. It’s nice to know there is a plan, as Taylor is aging. And it’s generous to offer up his dancers for the preservation of modern dance in general. But is that what today’s dance audience needs or wants? Clearly, the Graham and Limón groups have to infuse their rep with new works in order to attract an audience. If Taylor proposes to become a curator rather than a choreographer, he will be showing some modern dance classics that already have a showcase. (I can’t imagine that he’ll acquire works by Cunningham or the postmodern Trisha Brown works, as his dancers are not trained in those styles.) Would he bring in the work of Taylor alumni like Tharp, Parsons, Mazzini, and Corbin? Would that strengthen or dilute his programming? Is it naïve of Taylor to think that American modern dance still has some caché, considering there is so much fascinating new dance coming out of Israel, Europe, and Asia—and the U.S.?

Although I am asking these questions, I am not bemoaning the loss of modern dance as we once knew it. I guess I’m just more interested in seeing what’s happening in dance now, from all over the world, rather than capturing the heyday of a certain period. Maybe there’s another way to honor American modern dance—to appreciate how it’s grown and spread and sewn seeds far and wide. I would go to see a documentary film about that period, but prefer to see live dancing of our lives now.

Featured Uncategorized 9

Hi Wendy,

Paul Taylor will actually continue choreographing at least two new dances per year.

Thanks,

Lisa

Hi Wendy

Yes, I think the influence of the Modern Dance forms does continue today, however as contemporary dance transcends earlier forms it also should (or at least when it is healthy) include understanding of the earlier forms – so to transcend and include. Ignorance or avoidance of earlier ways of thinking about the body in movement, in my experience tend to be very short lived.

Jaime

These questions intrigue me greatly. I’ve had some conversations about these things and my main question goes back 50 years. It seems from Denishawn to Judson, the history of modern dance was one of rebellion and pioneering new forms. I don’t know who is doing that today. It feels (and I’m open to persuasion against this) like the innovation stopped with Judson, that the push for new forms, new techniques, dwindled away. Since that time, it’s mostly beena bout melding forms and techniques, which has brought about some good work, to be sure, but who are the pioneers? And once you push pedestrian movement to it’s extremes, where do you push to?

I think it’s important to preserve “classical” modern dance, even as new forms are devloping. If not, it would be like losing Mozart or Michaelangelo, never to be seen or heard again. Unfortunately dance, being a live art, takes constant maintenance. But the “visceral” quality you speak of makes it well worth it. This high tech society needs to be reminded of feeling.

As I understand it, Paul Taylor’s dancers will not be performing the “American masterworks”. Instead, companies will be invited to perform their own masterworks at Taylor’s annual Lincoln Center seasons. I believe that it can work, even though it feels a little forced.

I hope Paul Taylor’s American Modern Dance will somehow include artists that are not American born though. I agree, Wendy – How can one ignore work being made outside of the US? – There is so much going on!

In my view, what happened to modern dance was that, by the 1980s, the musical standards dropped so low, that choreography was no longer deeply connected to the music, or anything except the choreographer’s shallow moods. Without a fundamental relationship to music, dance is merely theatricalized (if it is) movement. It means choreographers must commit to working with living musicians and composers, to using existing scores composed for the purpose of dance (or at least theater), and not pastiches of unrelated music by one or several composers, as if the music exists for the choreographer’s convenience. Putting on a record and dancing to it may be fun, it could be theatrical, but it is NOT an ART.

You can also blame an overly short period of training, limited technical ability, and an overemphasis on athletics and acrobatics. As it takes many years of fine training to produce any artist, it takes many more years to become a creator. It also helps to read books, study art, to use artistic ideas from outside dance (note the word artistic), not vague concepts of post-modernism with no actual meaning.

Merce Cunningham found a clever vehicle for himself with chance, but it was a creative dead end, as it removed informed choice, the essence of art. Art is not about a trendy concept, it is not about being modern. It is, hopefullly, about being timeless.

The most essential ingredient needed, is for choreographers to have access to viewing the astonishing ballets produced for the Ballets Russes companies, particularly those by Fokine and Massine, and also Nijinska, to see what can be achieved, the superlative summits those masters reached, and with what fine music. It is not just about Martha and Doris and Jose. Those much-lauded movie musicals were pale imitations of the Ballets Russes.

Arts administrators are another disaster that has happened to dance. Too many companies, too small, needing cute dances that will please the audience and funders, leading to jukebox junk. We need something just like what Paul Taylor is wisely outlining, a major national company with the resources to perform the best choreographers with a live orchestra and commissions of new scores and new, gasp, librettos by scenarists, novelists, artists! I wish his company much success in its new direction, but we must also continue the life of the Martha Graham Company and the Limon Company. The fact is, the genius of the 20th Century is unlikely to be repeated, especially if the work cannot be seen in performance.

I, personally, believe in the classical values of balance, line, proportion and contrast, and that one dances because there is music to dance to. I think that is a good starting point, and if a budding choreographer maintains those values, their work may be worthwhile. It is also important to be musical, more esthetic than athletic, and there is an enormous amount to be learned from music. Repetition and motif, phrase and subject in particular. What is in the eye of the viewer? What will they remember and take away? What moment(s) will be indelibly etched in their memory? Many choreographers suffer from moverrhia, a continuous flow of constantly invented movement that becomes all-too forgettable. Movement must have grammar, just like language. And costumes and scenery. Fill the audience’s eye and tickle their senses. A dance by Geoffrey Holder was made unforgettable by the entrance of a dancer wearing a bathing cap with a big fuzzy knob on top. Omega Dance Company had an exceedingly simple dance about Edith Piaf that was utterly unforgettable. And all it contained were some gestures and a manege of pas-de-bourrees en tournant. It was the WAY it was danced.

I agree — it’s fundamentally about the music… not only in sound, but also in movement. The full range of time – space – energy is what’s missing, and I think it’s because dance study has become so disconnected from music in sound.

Dancers’ use of weight and gravity is different now than in early- through mid-20th century. This was noted by NY Times critics even back in the 1980s. That may be partly about lack of connection to music, but it’s probably more about today’s dancers’ ballet training — it waters down the strength of modern dance.

Third thing worth mention is the significance of modern dance for women in particular. This was a huge part of the break with ballet — women were dancing their own experience, and doing it as entrepreneurs. That point is often overlooked when talking about the important characteristics of early modern dance.

I was also at the same competition as a spectator. Because I visit Korea more frequently, it is no surprise to me that the Koreans were the most competitive. But I also note that they are older and clearly had more training than the Americans. I agree with Wendy’s observations, the style of Contemporary Dance in Asia is much more developed and compelling. In America, it seems aimless and unfocused.

For the past twenty years, some of the best young Korean and Chinese dancers have been going to Europe to seek better opportunities and the influence is clearly visible. In fact, for those who recall when the Guangdong Modern Dance Company came to the Joyce in 2000, a solo dance “I want to Fly” choreography by Xing Liang, already has all the high-contrast, visceral elements. See:

I want to Fly on YouTube

And I have seen many more from there.

However, I do not believe that Contemporary is the next evolutionary step for Modern Dance. From the dancing in the competition, I would say that Contemporary seems to be closer to ballet then modern.

Modern Dance began with the rebellion against ballet, the standardized, elite, centralized aesthetics of ballet. The crest of the wave might be passing, but the idea of individualism is timeless.

Therefore, to me, Modern Dance is the persistent call for the individual voice, not limited to contraction/release, fall/recovery, chance/rule or technology/nature. Martha Graham is much, much more than contraction/release, and Merce Cunningham is not just chance/rule. It is that which is out of the box and defining itself on its own by a singular artistic vision.

At the other end is every other dance style that have become centralized and standardized such as Ballet, Jazz, Broadway, Chinese Opera, Ballywood, Hip Hop, Break, Flex, Ballroom or, for that matter, Contemporary Dance. There are competition for all of them.

With all the individual artistic experimentation that is going on throughout America and all over the world, some based on ballet and some not, the individualistic Modern Dance is quite alive and well. A lot of dancers are still dancing without shoes or socks. My mother would tell you that’s modern dance. 🙂

We must keep Limón and Graham alive! They are the Modern Dance Masters we should never forget. My University studies taught us these Masters Techniques.Change does happen. But let us not forget our basic principles of Modern Dance Masters!