On May 2, the Danspace Project gala honored Wendy Whelan and Eiko Otake. I was happy to be asked to make the presentation to Whelan. Here is my tribute to her, and…really to both of them:

Fifteen years ago, I was watching a Balanchine piece at New York City Ballet. It was not one of my favorite Balanchines. I do love some of his ballets, but this one was orderly and symmetrical and courtly. And then this wind blew through the stage, rustling up the air and changing everything. The wind was Wendy Whelan.

This is what I wrote about her at the time: “Wendy Whelan, dancing the lead for the first time, makes her entrance — luxuriously, energetically, extravagantly billowing thither and yon… She is an impetuous creature… edgy, not quite human, threatening to elude the grip of her escort at every dive.” [This quote is in my book.]

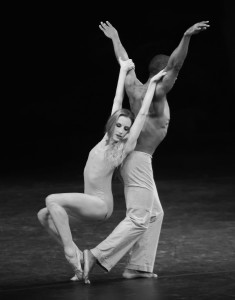

Whelan wih Josh Beamish in Restless Creature, photo by Christopher Duggan. Homepage photo by Nisian Hughes

She brought a modernist sensibility to NYCB. A simple passé became a revelation of the body’s architecture. She’s the epitome of what Annie-B Parson calls “fact-based choreography.” No frills, just the facts, like what Merce Cunningham demanded. She bypasses pretty and goes straight to beauty, a cut-glass kind of beauty, a beauty that elevates clarity to something spiritual.

She was a favorite of Jerome Robbins. She was fabulous in his woman-as-man-killing-insect ballet The Cage. “Jerry let me go with that one,” she told me. “I could use my weird assets.” You know, most ballet dancers don’t talk about themselves like that.

And she became a muse for Christopher Wheeldon. Her active participation in the making of his dances allowed him to be geometrically complex, at times supremely simple, and unexpectedly tender. Every time I saw her dance his After the Rain duet, I would get psyched to see my favorite details, like hands pressing together behind the back. Nobody else did it the way she did it. Watching Wendy, I understood the saying God is in the details.

Her quality of lightness is especially hard to describe. It’s not a feminine lightness. She’s not the typical balletic Sylph. It’s a lightness of the mind, a readiness to levitate, an affinity for the air.

Outside of NYCB, one of her gigs was with Peter Boal’s small company, which I had made a piece for. When Peter asked her to choose someone to choreograph on her, she did not pick a ballet choreographer. She chose Shen Wei. Later on, she worked with Stephen Petronio.

Whelan rehearsing Restless Creature, photo by Christopher Duggan

And then, still feeling restless, she came up with an idea to delve into contemporary choreography even more: She asked four very different dance artists to make a duet—and dance with her in that duet. They are Kyle Abraham, Brian Brooks, Alejandro Cerrudo, and Josh Beamish. The project is Restless Creature, which you can see at the Joyce later this month.

Wendy has become a leader in dance, not by making dances or by running a big company, but by being an interpreter of great depth, a co-conspirator in making new work, and a catalyst to bring ballet and modern dance together.

Since Danspace was started by a poet, as Claudia La Rocco reminded us in her Platform this spring, I want to pay tribute to Wendy Whelan and Eiko Otake for the poetry they have given us in dance. So I am going to read from—it’s not actually a poem, but—two sentences from my favorite essay by Merce Cunningham, “The Impermanent Art.” It’s from 1952 but he could just as well be talking about Wendy and Eiko.

“Dance is most deeply concerned with each single instant as it comes along, and its life and vigor and attraction lie in just that singleness. It is as accurate and impermanent as breathing.”

This tribute is also posted here on the Danspace blog site.

Featured Uncategorized Leave a comment

Leave a Reply