The Bolshoi Ballet is bringing three of its most traditional ballets to Lincoln Center Festival July 12 to 27. Of course audiences like seeing timeless classics like Swan Lake and Don Q. But Spartacus—that old warhorse from the Soviet era? The early pinnacle of Yuri Grigorovich’s endless career? Hasn’t the Bolshoi moved beyond Spartacus with artistic director Sergei Filin’s internationally savvy outlook?

Like some others, I’ve been grumbling about this conservative array. But to tell the truth, I have a secret reason for wanting to see Spartacus—actually two reasons: nostalgia and curiosity.

Back in 1962, when I was not quite 15, I was an extra in the Bolshoi’s previous production of Spartacus at the old Met on 39th Street. Yes, that’s right. Grigorovich’s famed version was not the first one. Experimental choreographer Leonid Yacobson created it for the Kirov (Mariinsky) in 1956 and restaged it expressly for the Bolshoi’s tour to the U.S. in 1962. And it was a disaster. I know. I was there, onstage with Plisetskaya and Vasiliev. The audience booed, the critics panned it. The last three performances of the eight scheduled were cancelled and replaced with Giselle.

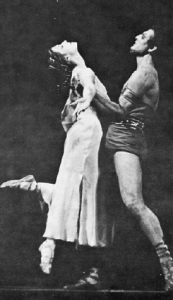

Maya Plisetskaya and Dmitri Begak in Yacobson’s version

But I have great memories. I remember being onstage at the old Met before the curtain opened, watching Plisetskaya warming up with a thousand knee-high prances. I remember the scale-like sequence of the brass players as they tuned up for Khatchaturian’s passionate, sensual, Eastern-tinged score—music that got under my skin. I remember the beautiful American-Russian corps dancer, Anastasia Stevens, who translated for us. And I remember the Bolshoi dancers singing songs from West Side Story backstage. (I’ve written about this whole experience in the memoir section of my first book.)

Who Was Yacobson?

In the brochure for the Bolshoi’s 1962 tour (under the aegis of Sol Hurok), it says, “Yacobson is one of the most ‘restless’ of our modern choreographers. He argues boldly and sharply about art and evokes violent arguments around himself…In his works not everything is precisely regulated or in proportion, for the irrepressibility of his characters hinders him from being patient, artistically ‘calculating.’ On the other hand, his work is always interesting for the audacity of his conception and… the boldness of his imagination.”

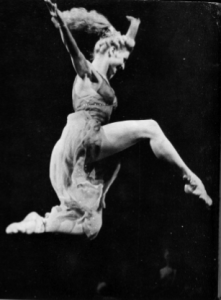

Natalia Ryzhenko as Aegina in Yacobson’s version

Well, that boldness got him into trouble this time. Yacobson, who died in 1975, was in line with the Soviet regime in wanting to pry ballet away from the elitism of the Czarist times. But his method of popularizing the art was to incorporate acrobatic and gymnastic moves. And, in the case of Spartacus, blatant sex scenes. In his depiction of degenerate Roman times, he staged Crassus’ feast as a huge orgy scene, the better to contrast with the purity and courage of Spartacus’ slave uprising.

But Soviet authorities didn’t want sexy, they wanted heroic. According to Christina Ezrahi in her book Swans of the Kremlin, some officials judged certain scenes to be “repulsively erotic”…hmmm, a precursor to the current Russian prudery? Think of the recent ban on discussing gayness, and the even more recent ban on obscenity.

Dance scholar Janice Ross has written that Yacobson was basically an artist of resistance. “One of the subversive, radical things in Spartacus . . . is that he makes it a very intimate, personal tale. At the core of it is a tragic love story about loss and longing.” Because of that very personal approach, Maya Plisetskaya, in her autobiography, declared him one of her favorite choreographers.

Not catering to good taste

In my teenage eyes, Yacobson’s Spartacus had many peak moments. Here are descriptions from my diary of September 11, 1962, of two of my favorite scenes.

CIrcus scene in Yacobson’s Spartacus

1. “The circus scene when men fight to entertain the people. It’s so exciting—just like the rumble in West Side Story—only in dance form. The choreographer, Yakobson, really did a good job on that. There are some more fighting scenes with Spartacus where they really use their shields and swords.”

2. “In the orgy scene a glamorous courtesan (played by the beautiful Natalia Ryzhenko) tempts Vladimir Vasiliev, as a slave. He’s blond and wears a red shirt and black tights. He’s cute as all hell and boy—can he dance! He does about eight arabesque turns which slowly change into attitude turns and his arms are behind his head. He starts feeling her up and everything, but when the courtesan doesn’t accept him, he goes wild and has these fits. In one part he jumps about five feet up and crashes down.”

At first, I was cast in the orgy scene. You were supposed to lounge around on bleachers, make out with your partner, and every once in a while tilt your head back and dangle a bunch of imaginary grapes above your mouth. Yacobson gave us instructions, through a translator, to be “sexy…oversexed” and to “make love, make love, make love!” I’d never had a proper make-out session in real life so I was very nervous. When my partner was reassigned to a different scene, I was excused from the orgy. Phew!

I don’t know if the booing was prompted by the “oversexed” treatment of the story, or, as my friend Rosemary Novellino-Mearns suggests in this posting, the fact that some of the world’s greatest ballerinas were wearing sandals and tunics rather than pointe shoes and tutus.

Put in context, the 1962 engagement of the Bolshoi in NYC was a month before the Cuban Missile Crisis—the scariest moment of the Cold War, when it really did seem like the U. S. and the USSR might destroy the world. Weirdly, it seems like there was some kind of offbeat mutual trust that the Bolshoi could bring this oddball extravaganza to our shores.

Grigorovich’s collaborative approach

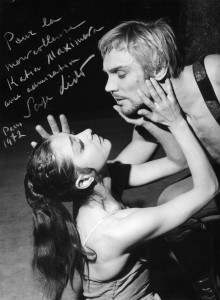

Ekaterina Maximova as Phyrigia and Vladimir Vasiliev as Spartacus in Grigorovich’s Spartacus, photo by Serge Lido

In any case, the powers that be in Moscow discontinued Yacobson’s 1962 version (though the Kirov kept his 1956 version in their rep). The quest for an uplifting revolutionary ballet (“the great truth of Soviet realist art”) escalated in urgency as the 50th anniversary of the 1917 Soviet Revolution approached. The Bolshoi decided to ask the young Yuri Grigorovich to try his hand at a Spartacus with less sex and more heroism. At first, according to Ekaterina Maximova’s memoir, he didn’t want to do it. But he complied, involving his four main dancers as collaborators: Vladimir Vasiliev as Spartacus, Maris Liepa as Crassus, Maximova as Phyrigia, and Nina Timofeeva as the courtesan Aegina. “We would discuss Yuri Nikolayevich’s ideas together with him, put forward our own, argue over them,” Maximova wrote. “He would listen to us and accept our suggestions.” This sounds so collaborative, so democratic, so not how Grigorovich is known to be now!

Love It or Hate It

Nina Kaptsova and Mikhail Lobukin, currently in Grigorovich’s Spartacus, photo by Elena Fetisova

Together the choreographer and dancers created the image of male heroism in the Soviet Union. Grigorovich became the figurehead of the “golden era” of Soviet Ballet. Larissa Saveliev, the former Bolshoi dancer who co-founded and directs Youth America Grand Prix, told me that it was Spartacus’ emphasis on sheer male energy that was so captivating. Grigorovich was less interested in specific steps than the story as a whole. In my conversation with Bolshoi Ballet’s artistic director Sergei Filin last April, he explained the ballet’s success to me by pointing out that it has a strong narrative flow and the “monologues” of the four main characters move the plot forward.

When it last came to NYC in 2005, New York Times critic John Rockwell called it “a grand cinematic spectacle, full of leaps and loves and betrayals and brilliant tableaus.”

Although no one has booed Grigorovich’s version as far as I know, it’s controversial in the sense that Americans and Russians react to it differently. American dance writers tend to find it propagandistic. Jennifer Homans, in her book Apollo’s Angels, describes it as the epitome of Soviet bravura—in both good and bad ways. “The Bolshoi kept going but after Spartacus, it was running on old energy, recycling past glories, fighting old ideological battles.” She clearly has no respect for the choreography. Although she says Vasiliev was thrilling in the lead role, she calls Spartacus a “degraded form of art” compared to Balanchine, Ashton, and Robbins.

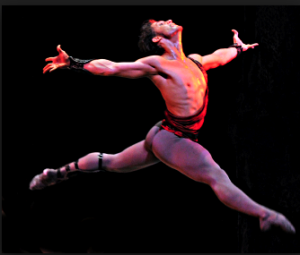

Ivan Vasiliev in Grigorovich’s Spartacus

Others praise the achievement of this enduring Spartacus but say the performance relies on a superstar like Vladimir Vasiliev in the 60s and 70s, or Ivan Vasiliev in the last few years. (Unfortunately Vasiliev the younger cannot dance it this month as he will be performing with Natalia Osipova at Segerstom Center for the Arts in California. View a YouTube clip of the elder Vasiliev in the role here, and the younger Vasiliev here.)

And then there is the view of Ezrahi, who believes that the ballet’s artistry trumps its original purpose as a government mouthpiece. I hope she is correct when she says the following:

“In the final analysis, ideological demands never managed to completely stifle the power of artistic autonomy. After the collapse of communism, Spartacus has survived the death of the political system that had provided the context of its creation. Today the ballet stands as a reminder that despite the political-ideological demands…artistic imagination proved to be remarkably resilient, creative, and enduring.”

Featured Uncategorized 2

I’m looking forward to seeing my first Spartacus in two weeks!

It is interesting that it is now considered a “warhorse” guaranteed to pack the house. When, as you point out, it had mixed reviews the first two times the Bolshoi brought it to the US.

My favorite review from Lillian Moore in 1962: “The brash vulgarity of Spartacus could be forgiven if it were entertaining…”

Thank you for that biting statement from Lillian Moore. Not long after that, she was one of my favorite teachers at the Joffrey School. A very kind person. Where did you find that review?