What Was Judson Dance Theater, Who Was Against It, and Did It Ever End?

Ten years ago, on the 50th anniversary of Judson Dance Theater (JDT), which started on July 6, 1962, the Danspace Project presented “Danspace Platform 2012: Judson Now.” I was invited to contribute an essay from my point of view. I told the origin story as I understood it, inserting my personal connections as “asides.” Now, on the 60th anniversary, I feel I want to emphasize the aspect that doesn’t get into the history books: how the dance establishment put up roadblocks to Judson. JDT is now a canonical part of dance history, taught in colleges across the country, so it’s hard to imagine that the Judson dancers were rejected by the dance establishment again and again. To mark the 60th year, I’ve augmented the title to reflect that resistance, and I’ve tweaked and updated the essay with current information.

Judson Dance Theater was a confluence of people and ideas that reflected the defiance of the 1960s. It questioned authority, challenged artistic assumptions, and favored “ordinary” over virtuosic. And it changed modern dance forever.

More specifically it was a collective of dance and other artists who showed their work at Judson Memorial Church in a series of sixteen numbered concerts from July 6, 1962 to April 29, 1964 (though not all of them were actually at the church). The group evolved out of weekly workshops taught by Robert Ellis Dunn, a protegé of John Cage, at the Merce Cunningham studio. Using Cage’s experimental approach, Dunn infused the proceedings with a sense of discovery. As Yvonne Rainer has said, “There was new ground to be broken and we were standing on it.”1

We look back today and see that Judson was the crucible for postmodern dance, Contact Improvisation, and a new way to look at dance/art collaborations. The influence of Judson is so pervasive that it affected almost everyone in the downtown scene, and it’s rippled outward nationally and internationally. Mikhail Baryshnikov’s Past Forward project in 2000 gave us a chance to trace those beginnings and see work by Rainer, Steve Paxton, Trisha Brown, Deborah Hay, David Gordon, Lucinda Childs, and Simone Forti. (When I interviewed Baryshnikov for an article about it he called them all “beautifully crazy.”2)

Twenty years earlier, when I was on a college dance faculty, I initiated the Bennington College Judson Project, which comprised a series of residencies, video interviews, and a touring exhibit. I wanted students to know about Judson and catch the fervor of experimentation. We had residencies at the college where students performed Rainer’s We Shall Run and took workshops with Trisha Brown and Steve Paxton. Students were part of a team that interviewed about twenty Judson artists for the traveling exhibit.3

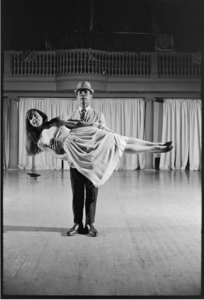

Steve Paxton and Trisha Brown during Bennington College Judson Project residencies, 1980, ph Tyler Resch

In 1982 we partnered with Danspace Project to produce two programs of reconstructions of works by most of those mentioned above as well as by Elaine Summers, Judith Dunn, Aileen Passloff, Remy Charlip, Philip Corner, Edward Bhartonn, and Carolee Schneemann. From Charlip’s sweetly bizarre Meditation, in which he distorted his facial expression in slow motion, to Bhartonn’s five-second back flip that popped a balloon, to Schneemann’s Lateral Splay, in which people ran headlong until they crashed into another person, a range of spirited work delighted the Danspace audience. I was grateful that Jack Anderson, who had been around in the early ’60s, wrote an illuminating advance story in The New York Times titled “How the Judson Theater Changed American Dance.”

Aside #1: The Bennington College Judson Project photo exhibit traveled internationally. We opened at Grey Art Gallery at NYU, and I remember Elaine Summers looking at the walls and saying, “Why is this considered history? It was only twenty years ago.” She was right, of course. But to me, who had missed the whole Judson era, it was history, and there was something compelling about that history to a young choreographer like myself.

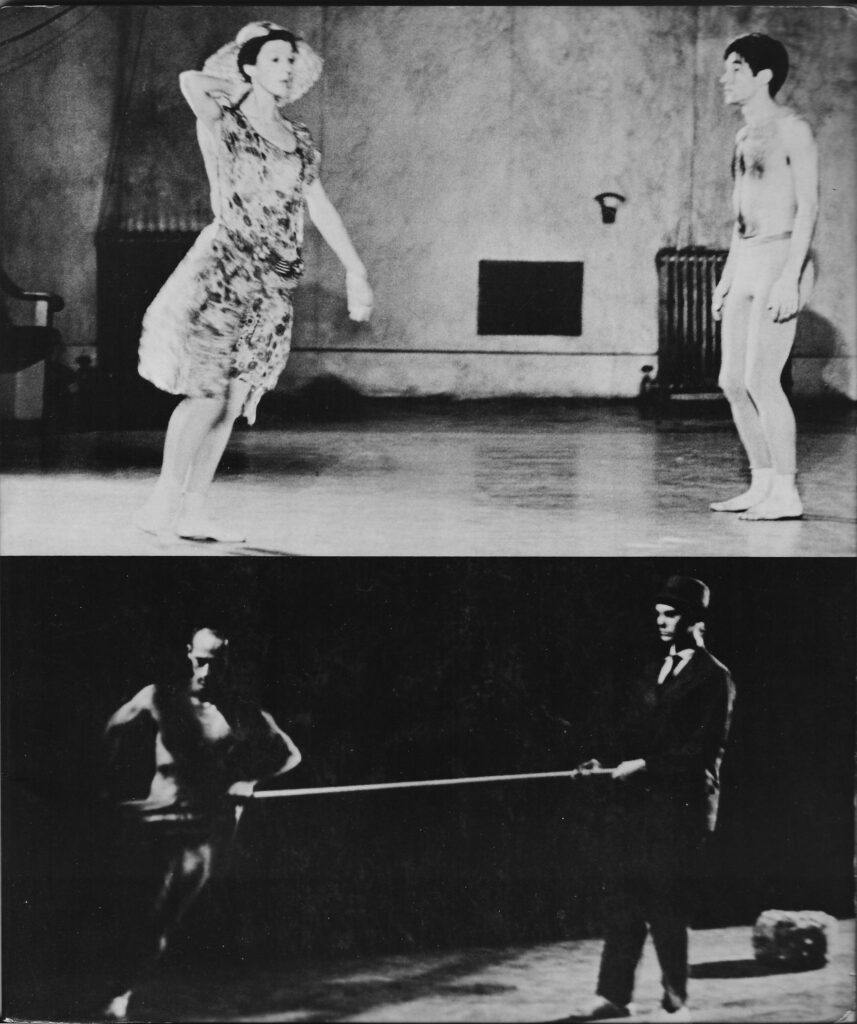

Cover of Bennington College Judson Project catalog. Above: Random Breakfast by David Gordon with Valda Setterfield (1963) ph Peter Moore. Below, Waterman Switch by Robert Morris with Lucinda Childs, ph Peter Moore. Design by Linda Lawton.

Like earlier periods of interdisciplinary activity—the Diaghilev era, Dadaism, and the Bauhaus—Judson’s burst of experimentation was ignited by both strong individuals and an esprit de corps. As Elaine Summers said in the BCJP interview, they stimulated, challenged, and cross-pollinated with each other.4 The original Judson group eventually broke apart as each of the artists went their own way. Narrowly defined, Judson Dance Theater ended in 1964 or 1966, depending on whom you talk to. In a phone conversation with Paxton, he said that “Judson” never ended. He pointed out that some of his peers were still making dances and that Judson Church, thanks to Movement Research, was again presenting dance.5

I took Steve to mean that Judson had a lasting effect and that the modern dance world didn’t snap back to where it was. Sure, the Martha Graham and José Limón companies soldiered on, reinventing themselves as repertory companies. But postmodern dance surged ahead, shaped by the troublemakers at Judson, continually changing and adapting to today’s world.

It’s in that spirit, the sense that Judson is still with us, that I offer the following account of how this explosion of experimentation came to be—and how it almost didn’t happen.

Robert Dunn’s Workshops

In 1960, John Cage asked Robert Dunn to teach composition in the Merce Cunningham studio, which was then on Sixth Avenue and 14th Street in a building owned by the Living Theatre. A pianist who accompanied classes at the Cunningham studio as well as at other dance centers including Juilliard (and a former tap dancer), Dunn had taken Cage’s famous course in experimental music at The New School for Social Research. Borrowing from Cage’s ideas of indeterminacy, he gave assignments in the form of scores. The idea was to get away from one’s own clichés in generating movement. They might be chance scores—for example one student used the rotation of the moon as a score6 —or they might be a simple time structure, as in “Make a three-minute dance.”7

Dunn’s discussions in class were fueled by curiosity rather than judgment. He asked students about process rather than declaring whether a study was good or bad. Describing what he was aiming for as a teacher in those days, he wrote:

From Heidegger, Sartre, Far Eastern Buddhism, and Taoism, in some personal amalgam, I had the notion in teaching of making a “clearing,” a sort of “space for nothing,” in which things could appear and grow in their own nature. Before each class, I made the attempt to attain this state of mind.8

He favored “the ordinary” as a way to mesh art and life (another Cagean concept) and to avoid the drama of modern dance and the vagaries of “personal taste.”9 Rainer, who was one of his first five students, caught on early:

His appreciation for the unpredictable and the unexpected in art was profound. “Do something that’s nothing special” was one of his challenging assignments. At that moment I got up from the floor and walked to an opposite corner of the studio while unbuttoning and removing my sweater, then returned and sat down as I put it back on. His approving, bemused gaze made my day.10

Dunn’s approach departed sharply from that of Louis Horst, the reigning composition teacher of modern dance (and Graham’s musical director and sometime lover). Horst taught students to adhere to formal musical structures like a rondo or a sarabande and to give each study a theme. Dunn had accompanied both Horst’s and Doris Humphrey’s composition classes and felt the atmosphere was stifling.

With Dunn as catalyst, the group fairly erupted with creative solutions. After about a year and a half, the students set out to look for a place where they could show their short pieces.

A Clear “No” From the Dance Establishment

The kind of heroic look that Graham and José Limón projected, while it was right for their times, did not speak to the downtown dancers of the ’60s. To them the early moderns appeared imperious, rigid, inflated.

Nevertheless, Dunn’s students approached the 92nd Street Y, the stronghold of modern dance, to audition their studies for its series. David Gordon remembers that he, Rainer, and Paxton lined up, one by one, to show their dances, and he remembers that they were all rejected, one by one. (Update as of 2022: His memory was incomplete because Ruth Emerson, as well as Lucinda Childs, were accepted and did perform in the Young Choreographers series.) The jury panel included Marion Scott, who taught Humphrey-Weidman technique; choreographer Jack Moore, who had danced with Anna Sokolow and was a co-founder of Dance Theater Workshop in 1965; and Lucas Hoving, who had danced major roles with both Kurt Jooss and José Limón. The old guard, but not so old at that point.

Years later, Jack Moore told Rainer, referring to the Y’s rejection of the Dunn Dunn group, “We made a mistake.”

Aside #2: Not only did Jack regret their decision, but when he taught his own composition classes at Bennington in the late ’60s—which I attended—he seemed to have taken a page from Robert Dunn’s book. When responding to a student showing, he would always ask, “How did you make that? What was your process?” Even though Jack had been an assistant to Louis Horst, he later followed the Dunn route rather than the Horst route.

The Y’s rejection was a lucky “mistake.” It sent the young dancers looking for a more informal venue, and they found Judson Memorial Church in Greenwich Village. Rainer knew that the church was already hosting Judson Poets’ Theatre and Judson Art Gallery. It also had a long tradition of anti-war activism and other socially progressive programs like abortion counseling.11 Senior minister Al Carmines, backed by Reverend Howard Moody, welcomed the stray dancers with open arms and spaces.

It was a time when the other arts were also breaking with the past. The Beat poets were extolling spontaneity and Andy Warhol was making pictures of soup cans instead of sunsets. Steve Paxton, who was influenced by the experimental, anarchistic Living Theatre, described his own sense of liberation: “The work that I did there was first of all to flush out my ‘why-nots’…‘Why not?’ was a catchword at that time. It was a very permissive time.”12

The first concert at Judson, a mixed-media marathon of twenty-three pieces by fourteen artists on July 6, 1962, lasted more than three hours. Jill Johnston, writing in the Village Voice, called it a “democratic evening of dance.” About both Yvonne Rainer and David Gordon, she wrote that they “did some movement nobody ever saw before.” In reaction to the whole evening, she said, “the audience responded tumultuously and we had good reason.” She concluded by prophesying that this group would be the exciting thing in dance in twenty years.13

For Rainer, the first concert was momentous: “I remember the exhilaration afterward,” she said years later. “We found a genuine alternative to what had been happening.”14

Like Parents: Cunningham, Cage, and Halprin

Some of the Judson artists were dancing in Cunningham’s company: Paxton, Judith Dunn (wife and assistant to Robert Dunn), Deborah Hay, and Valda Setterfield (who did not make dances herself but helped Gordon develop his work through her performances). Additionally, Cunningham dancers Carolyn Brown, Barbara Dilley (Lloyd), and Albert Reid occasionally performed and/or choreographed at Judson.

Aside #3: I danced with Albert Reid in a trio he made in the early 70s. Long lines, clear shapes, and the recorded sound of a distant bagpipe. It was the Apollonian side of experimental dance.

Cunningham and Cage had shattered the usual A-B-A compositional structure, de-centered the stage space, and—most notoriously—severed the conventional relationship between dance and music. The simultaneity of unrelated sound (often deafeningly loud) and Cunningham’s all-over stage picture forced the audience to rely on itself. The music was one thing, the dance was another, and in your perception, you created a third thing.

One of Cage’s basic tenets was that any sound could be music. Theoretically, that could extend to dance: Any movement could be dance, right? But Cunningham’s movement vocabulary stayed squarely within the realm of dance technique. It was left to the Judson group to pry open the vocabulary to include pedestrian or awkward movement. It was partly this difference that led Rainer to say ruefully in 2001, “As Cunningham always said, we were John’s children and not his.”15

Hay articulated another way they were Cage’s children. When I was on a panel with her many years later, I asked her what it was about Cage’s presence within the Cunningham company that had influenced her. “His sense of play” was her immediate reply.

Aside #4: At a Danspace Project benefit in 1977, I saw Cage “play” a set of cactus plants. He plucked them with a look of loving concentration and listened to the amplified sounds they made with childlike glee.

Halprin’s Branch Dance, c. 1957, with A. A. Leath, Halprin, and Simone Forti. Ph Warner Jepson, Jepson estate, via Museum of Performance + Design

If Merce and John were the artistic fathers of this motley crew, then Anna (known then as Ann) Halprin was the mother. Rainer, Trisha Brown, Simone Forti, Ruth Emerson, Sally Gross, and Meredith Monk all studied with her on her outdoor deck in Marin County, California. Halprin’s focus on task, collectivity, and communing with nature was absorbed as an alternative way to generate movement. Her strong connection to nature particularly influenced Forti and Brown.

Aside #5: I finally got to take a class with Anna. In 2010, Movement Research sponsored a workshop at Judson Church, the first time she’d ever been there. At 93, she led the two-hour session without ever sitting down! In 2014, I participated in her Planetary Dance, a powerful community ritual, which I called “Anna Halprin’s Drugless Woodstock.”

Hints of Democracy

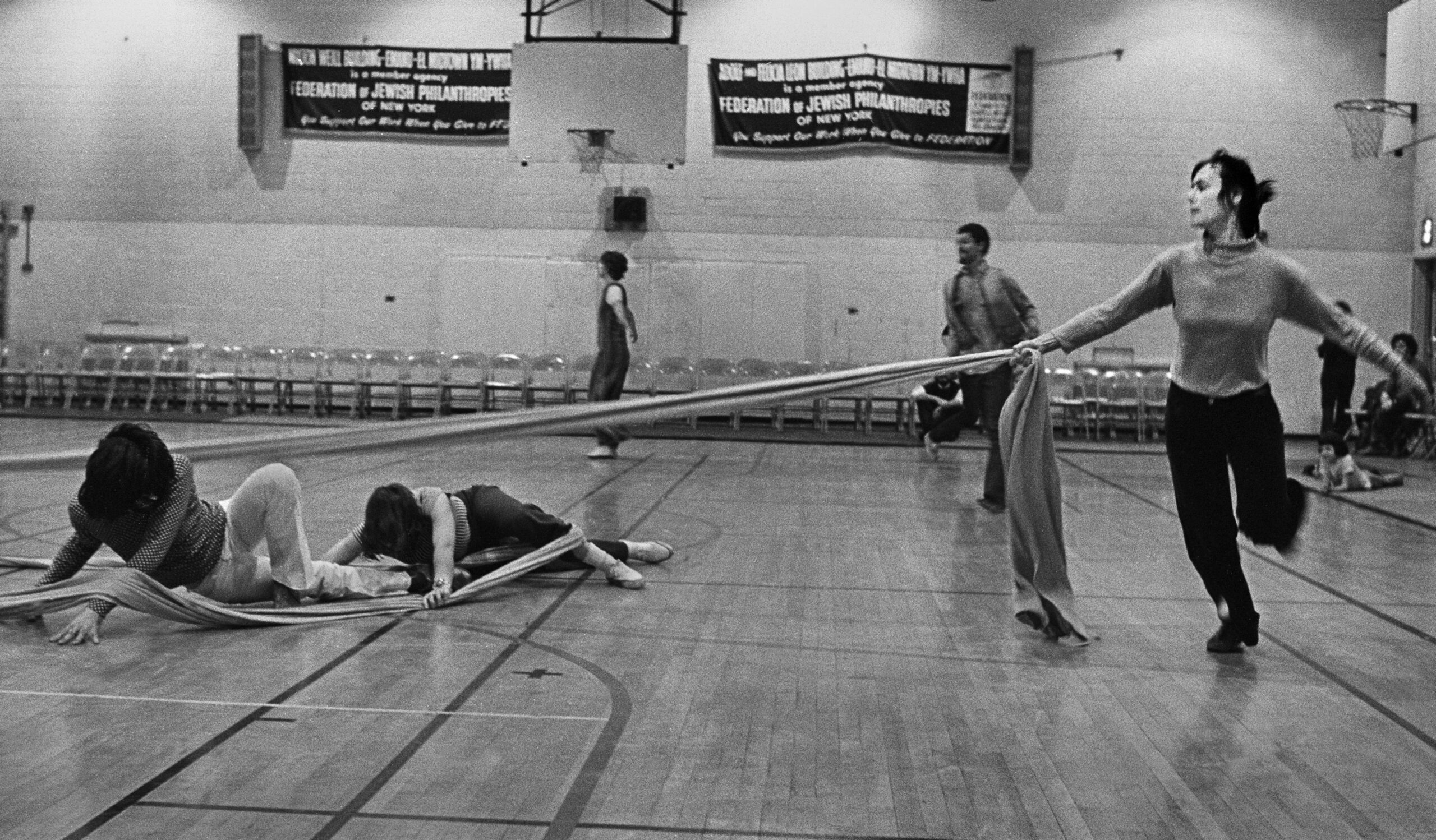

Some of Paxton’s dances, for instance Flat (1964), consisted mostly of him walking and occasionally freezing mid-action. In Satisfyin Lover (1967), he extended his solo walking to a group. Jill Johnston rhapsodized over the vision of democracy that emerged from Paxton’s casting:

And here they all were in this concert in the last dance, 32 any old wonderful people in Satisfyin Lover walking one after the other across the gymnasium in their any old clothes. The fat, the skinny, the medium, the slouched and slumped, the straight and tall, the bowlegged and knock-kneed, the awkward, the elegant, the coarse, the delicate, the pregnant, the virginal, the you name it, by implication every postural possibility in the postural spectrum, that’s you and me in all our ordinary everyday who cares postural splendor.16

Democracy was not only a value onstage but also backstage. Once the group moved into the church and Robert Dunn was no longer the guide, they held group meetings. Anyone who came to these meetings could show a work on the JDT programs. The discussions about each other’s works were led by a different person each time. Ruth Emerson introduced the Quaker idea of consensus to the proceedings, meaning a decision wasn’t made until everyone agreed.17 18

Composers, Poets, and Painters Jump In

The interdisciplinary seed had been planted at Black Mountain College in 1952— in the dining hall. That summer Cage organized Theater Piece No. 1, an event that Carolyn Brown called a “collaborative non-collaboration:” Cage gave a lecture with timed silences; Cunningham improvised in the aisles (followed by a frisky dog); Charles Olson read poetry from a ladder; David Tudor played the piano; and the young Robert Rauschenberg suspended paintings above the audience, which was seated in the middle of it all.19 This event is sometimes called the first happening, or a proto-happening.

At Judson, Rauschenberg and other visual artists like Robert Morris and Alex Hay caught the performance bug. John Herbert McDowell, Philip Corner, and Malcolm Goldstein composed music for the dancers and also made their own performance pieces. Poet Jackson Mac Low, a member of Fluxus, worked closely with Forti (who, though an influential member of Dunn’s class, did not perform at Judson because of a personal issue). Schneemann created rambunctious, almost violent group works at Judson. Her Meat Joy (1964), with partially nude people rolling around on the floor amidst raw fish, chickens, and sausage, introduced a streak of hedonism.

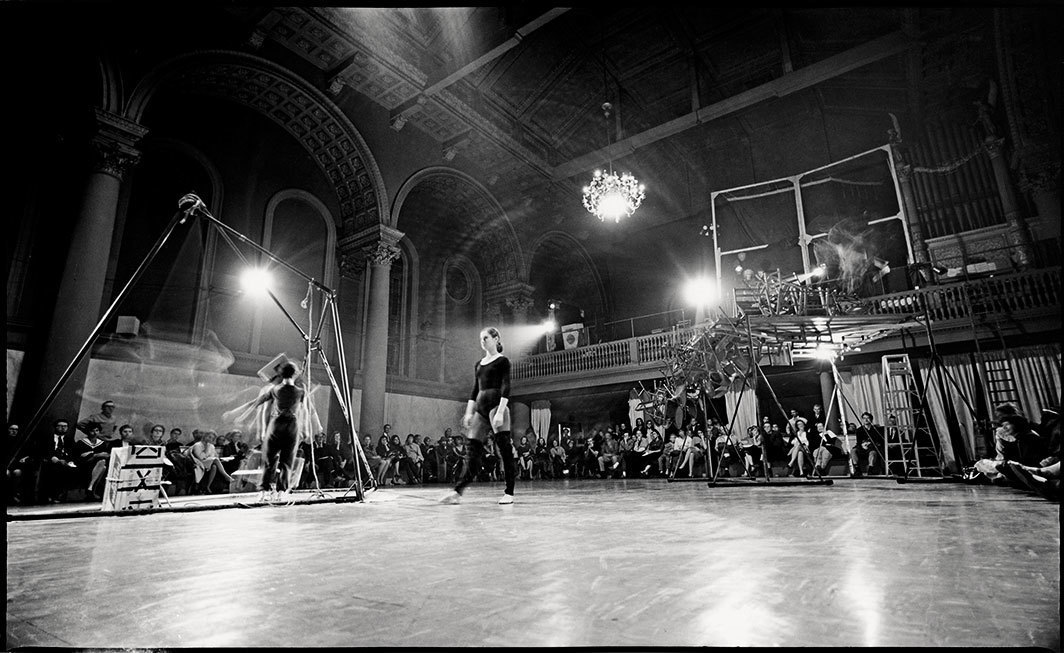

The most remarkable dance-art collaboration at Judson was initiated by sculptor Charles Ross, who had worked with Anna Halprin on the West Coast. Ross proposed to build a set for Concert #13 that the dancers could use as they wished. The result was a huge trapezoidal swing-set-type structure in the center plus a moving set (what Rauschenberg later called “live décor”), which was Ross himself piling up hundreds of chairs to create a raised platform at one end of the sanctuary. Each choreographer of that evening had to confront the new environment; they included Ruth Emerson, Rainer, Deborah Hay, Alex Hay, Lucinda Childs, Carla Blank, and Carolee Schneemann. Childs called it “a very beautiful environment to work in.”20 The periods of “free play” in between dances made it seem like the evening was one long piece.21

Tilting Toward Visual Art

Even before JDT started, Forti, who had been a painter before studying with Halprin in San Francisco, thought of her dance work as sculptures. In this essay, I wrote about the ways that Forti carried Halprin’s body/mind philosophy from West to East, from the outdoor deck in the Bay Area to Dunn’s workshop in New York. When she was invited to present an evening at Yoko Ono’s loft on Chambers Street in 1961, she came up with the concept of dance constructions. She designed objects that controlled how she moved—as though the object itself were the score. For instance, Slant Board (1961), required performers to walk (or stagger) across a steeply raked surface while holding ropes that were nailed at one end to the board. The construction of the wooden ramp and the physical task were essential to each other. The dance constructions merged Halprin’s idea of functional movement with Dunn’s idea of chance methods and ordinariness. It also put dance and art on an equal footing.

Aside #6: When I was touring with Trisha Brown in the mid-70s, audience members at our lec-dems would ask her, “Why don’t you use music?” She would quip, “Do you expect to hear music when you walk around a sculpture in a gallery?”

For Trisha Brown’s Floor of the Forest (1970), which has been reprised at several museums, the audience does indeed have to walk around to watch the dancers, strung out on horizontal cargo netting, from different angles. You catch sight of the two dancers slithering in and out of clothing only by changing your position. So the members of the audience, bending and stretching to be able to see, become part of the performance.

Aside #7: The first time I saw that piece, it was a variation called Rummage Sale and Floor of the Forest, in which people were selling off their old clothes while, above them, Trisha and Carmen Beuchat were crawling in and out of the clothing tied to the cargo net. It was a hilarious example of art and life meshing.

The Released Body

Hand in hand with the favoring of ordinary movement came the ordinary body. In her chapter “Everyday Bodies” in Time and the Dancing Image (1988), Deborah Jowitt describes how Halprin’s less dancerly stance of the body fit with the task idea:

[She] utilized improvisation to get past dance clichés to more basic human responses. Such improvisations—“tasks”—had a forthrightness that helped set the tone of the ’60s; by casting the dancer as a decision-maker, intent on solving a particular problem, they inevitably presented him/her as a wily, alert individual…To the Judson generation, the body in all its states was acceptable. Clumsiness could figure in dance as well as adroitness, plumpness as well as trimness. Even weakness could play a part. (In 1967 Rainer performed Trio A while in the shaky state that followed a serious illness and called it Convalescent Dance.)22

Elaine Summers never studied with Halprin but had a strong affinity for her work: relaxed bodies, structured improvisations, and group awareness. Summers had gone to Juilliard as a special student but soon noticed pain creeping into her joints. She spent years developing a more easeful way of moving, which led her to the “ball work,” also known as kinetic awareness. Her approach to healing was consistent with the more “ordinary,” relaxed body of the Judson dancers.

Aside #8: Trisha once told me that part of the reason she asked me to dance with her, sight unseen, was that she knew I had studied with Elaine. She trusted anyone who worked with Elaine. And P.S., I still do the ball work every day.

Demystifying the Making Process

The seeds of JDT blew elsewhere and took root. Judith Dunn, who had assisted in Robert Dunn’s workshop and created many works for Judson, brought some of the concepts with her when she took a teaching position at Bennington College in 1968. One of the students, Susan Rethorst, took her tutorial in 1974. In her book on choreography, Rethorst describes how formative Judith Dunn’s class was for her:

The idea was to make and show a dance every day from September to June. We were given no starting points, no themes, no methods and no class time to work. Each day I had to find a way, and the time, to make a dance… I had many expectations going into this—I would run out of ideas (I did), that I would be intimidated by the task (I was), but mostly I was curious. I wasn’t able to imagine what the experience would be like, or what it would teach me. Well, it made me a choreographer. It rearranged all my assumptions about how dances get made. It showed me that my ideas will present themselves to me via dances; that my dances know more than me. The form of the class—the dailiness it necessitated—brought choreography, and indeed all art, down from the mountain I had found it on all through my suburban childhood. Art, I saw, was something done by people with all their limitations and messes.23

Another dance artist strongly influenced by Judith Dunn was Dianne McIntyre, who studied with Dunn and her partner, the Black jazz trumpeter Bill Dixon, at Ohio State University shortly before they came to Bennington. McIntyre felt the pair opened doors to improvisation. Dunn talked about “inner time consciousness,” and Dixon brought an awareness of the Black jazz traditions of improvisation.24

Aside #9: In 1971, I was knocked out by Day 1, a thrillingly kinetic—and suspenseful—performance by the Judith Dunn/Bill Dixon group at the Cunningham studio. The idea of this racially mixed group was that dance and music were equals but didn’t control each other. As in jazz music, the relationship between each individual and the group was kept in exquisite balance. 25

Radical Juxtaposition

This term, used by Susan Sontag in her essay “Happenings: an art of radical juxtaposition,”26 drew on the principle of collage: that two or more very different objects or images placed side by side would challenge habitual ways of seeing. When extended into a time-based art, this can mean simultaneous actions that are radically different. In Rainer’s full-evening work The Mind Is a Muscle (1966), her strictly planned movement episodes (including the now iconic solo, Trio A) were accompanied by wooden slats being hurled down from the balcony above, clattering to the floor with headache-inducing regularity.

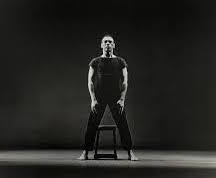

Here are three other examples of radical juxtaposition from Judson and after: 1) Lucinda Childs’ Carnation (1964), in which she crowned her head with a colander and stuffed sponges into her mouth, all with a demeanor of utmost solemnity. 2) David Gordon’s Mannequin Dance (1962, reprised at Danspace Project as a part of “Platform 2012: Judson Now”), in which he wiggled his fingers and sang songs from musicals while James Waring (a major figure who influenced Gordon and others) passed out balloons for audience members to let the air out slowly, providing a squeaking accompaniment. 3) Rudy Perez’s Countdown (1966), in which he sat on a stool, streaked his face with war paint, then rose and smoked a cigarette, all in slow motion, to the operatic strains of “Songs of the Auvergne.” It was mesmerizing.

Aside #10: I danced with Rudy from 1969 to 1970 and remember his flair for pairing movement with sound. At one point when we were inching along in tiny steps, the recorded sound of rain came on, seemingly unrelated, and Rudy had us look upward as though feeling the drops on our faces.

Nudity, Naturally

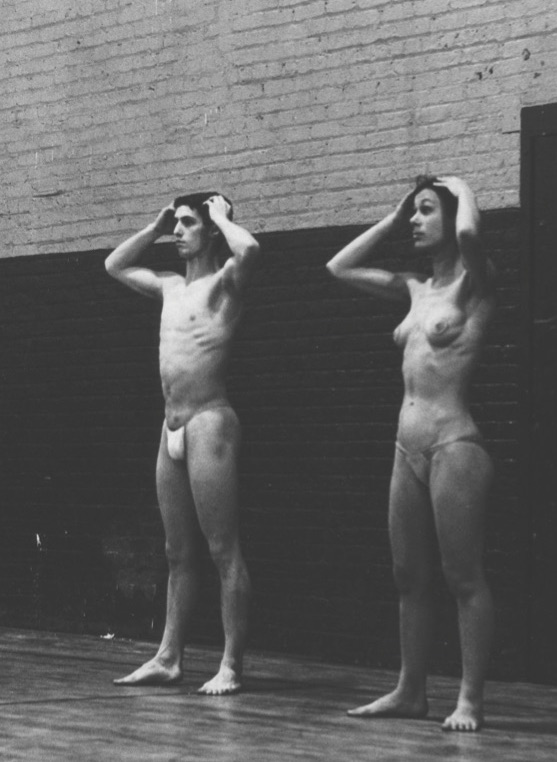

The ’60s were rife with “sexual liberation,” encounter groups, and general permissiveness, so it was almost inevitable that nudity would reach Judson Church. For the collaborative duet Word Words (1963), Rainer and Paxton chose to dispense with costumes because, as Rainer said later, “Nudity was in the air.” But the sanctity of being in a church brought on a sudden bout of modesty: She wore pasties and they both wore G-strings.

Word Words (1963). Paxton and Yvonne Rainer. Photo by Al Giese, courtesy of Bennington College Judson Project.

In 1965, Robert Morris’s Waterman Switch set off a furor. In one section, Morris and Rainer were locked in nude embrace while taking baby steps. Word got out, causing a scandal, and Judson Church was almost ousted from the American Baptist Convention. Reverend Howard Moody asked Al Carmines to write a defense of nudity in the church, which was so eloquent that Moody called it “a primer for understanding the power of art.”27

That same year Halprin made Parades and Changes, in which the dancers slowly undress and dress again. This section is ritualistic rather than seductive. After performing the piece without incident in Europe, she brought it to the Hunter Playhouse in Manhattan. Because of the pre-performance buzz, a warrant for her arrest was issued, but Halprin left the city before she could be summoned.28

Aside #11: At the 2004 Dance Magazine Awards, Clive Barnes told a funny story about being called in as a witness to testify under oath whether or not he had been aroused by the nudity in Parades and Changes.

Improvisation—Breaking the Hierarchy

From Anna Halprin some of the Judson dancers had learned to love improvising. Not only did it free the body, it also broke the usual hierarchy of the choreographer telling the dancers what to do. Halprin gave structures or scores and let the dancers discover their own ways of fulfilling them.

The fusion of improvisational task dance and the Cagean sense of play reached its peak—a very heady peak—with the Grand Union, performing their mayhem from 1970 to 1976. The gloriously idiosyncratic personalities (Rainer, Paxton, Gordon, Brown, Douglas Dunn, Barbara Dilley, Nancy Lewis [Greene], and, only early on, Lincoln Scott and Becky Arnold)29 combined spontaneity and planned maneuvers (the group hoist, the pillow business, the doctor-patient scenario), as they played out personal rebelliousness in a collective context. Intertwining fiction and fact, they were as nimble verbally as they were physically.

Aside #12: Paxton would occasionally take the mic and spin a story about Trisha the Wild Child. It went something like this: “She grew up in the woods, was raised by coyotes, slept in trees, and could foretell the weather. By age 7, her teeth were broken and stained with blackberry juice.”

Grand Union May 1971. From l,eft: David Gordon, Becky Arnold, Nancy Lewis, Lincoln Scott, Yvonne Rainer, ph James Klosty.

In every Grand Union performance, there was the potential for their spontaneous material, aka their “collective genius,”30 to fall flat or to soar. I loved their performances so much that I wrote a book about the group.

Recently, as a kind of adjunct to my book, I captured the voices of Yvonne Rainer, David Gordon, Steve Paxton and Trisha Brown talking about various aspects of JDT and Grand Union, for a Pillow Voices podcast called “Grand Union: Democracy or Anarchy?”

Ripples—and Chokings—in the Press

The only two critics who covered the Judson scene regularly were Jill Johnston in the Village Voice and Allen Hughes in the New York Times. Johnston, whose dance writings are collected in Marmalade Me (1971), wrote in excited, witty, trippy, brilliant, insightful, prose. In critic George Jackson’s words, “What she had given her readers was the feeling of dance being born.”31 Hughes, a music critic new to dance, wrote that Judson was “creating a splendid chaos.”32 He was castigated by some in the dance establishment for his attention to Judson, which may have contributed to him being taken off the dance beat.33

The most venerable dance critic on a daily paper at the time was Walter Terry, who had been at the New York Herald Tribune since 1936. Terry was generally dismissive of the avant-garde and did not often deign to cover it. About one concert at Judson in 1968, he wrote, “none of this is really new.”34

On the opposite end of publications was The Floating Bear, a homemade newsletter co-edited by Beat poets Diane Di Prima and LeRoi Jones. This free mimeographed dispatch, with contributions by other Beat writers like William Burroughs, was sent out to a small circle of subscribers. Its values were similar to those of JDT: experiment, try new forms, don’t worry about producing masterpieces. Among those who helped edit and deliver it were two dancers in the Judson circle: James Waring, and Fred Herko, who was Di Prima’s best friend and the ballet dancer of Judson. So it was almost familial when Di Prima reviewed the first Judson concert. (LeRoi Jones later became Amiri Baraka, a force in the Black Arts Movement.)35)

Last page of Jackson’s 1964 feature on the avant-garde for Dance Magazine, picturing Yvonne Rainer in Three Seascapes.

Dance critic George Jackson published an enthusiastic six-page cover story on JDT in the April 1964 issue of Dance Magazine, complete with striking photographs by Peter Moore. Titled “Naked in Its Native Beauty,” it spoke frankly, and with some awe, about the controversial nature of the experiments at Judson and other downtown dives. Jackson pointed out that these dancers and artists had no wish to assume a character or to create a theatrical arc, but they were devoted to “simply being themselves” in their “real virtues and vices.”36

Aside #13: George told me that he actually wrote it in 1963 and submitted it to the Dance Observer, Louis Horst’s publication. He said that Horst became so angry that he slammed down the phone and never spoke to him again. (Horst had devoted his life to elevating modern dance as an art for the concert stage.)37 George then took his story to Lydia Joel, editor of Dance Magazine. She demurred because people in the dance establishment did not feel Judson warranted coverage. It was only at the urging of critics Edwin Denby, Doris Hering, Walter Sorell, and the German writer Horst Koegler that she finally decided to print it.

Two months later, in the July 1964 issue, two letters to the editor attacked Jackson’s article. One of them, signed only with the initials L. T. R., wrote, “How can you waste all those pages on that so-called ‘avant-garde’ nonsense? . . . It has no present, no future, and above all, no merit . . . Readers of your magazine buy it to read about dance not about remotely related idiocy.”38

Silence as Both Rebellious and Spiritual

The Zen-influenced Cage was so interested in silence that the word became the title of his first collection of writings in 1961, published by Wesleyan University Press. Cunningham created his dances in silence and added music at the last minute. Many of the Judsonites choreographed without music. As Jackson had written in his Dance Magazine feature, he saw “a freedom from the rhythms and forms imposed by music.”39 Rainer even wrote an amusing screed against music for dance:

The only remaining meaningful role for muzeek in relation to dance is to be totally absent or to mock itself. To use “serious” muzache simultaneously with dance is to give a glamorous “high art” aura to what is seen. To use “program” moosick or pop or rock is to generate excitement or coloration which the dance itself would not otherwise evoke. Why am I opposed to this kind of enhancement? One reason is that I love dancing and am jealous of encroachment upon it by any other element. I want my dancing to be the superstar and refuse to share the limelight with any form of collaboration or co-existence. Muzak does not accompany paintings in a gallery nor does it encroach on the dialogue in a stage play.40

The non-defiant, calm aspect of silence was appreciated by the Judson Memorial Church congregation. Al Carmines, the minister who had welcomed the dancers in the first place (and a brilliant composer/lyricist in his own right), wrote about the effect this new group of artists had on his services:

The influence on our worship has become increasingly clear. I doubt, for instance if we would have had the courage to have a period in our service which was simply opened up to the congregation for statements and concerns—had we not first seen the insouciance with which the dancers could allow the unexpected to enter their concerts. The importance of the gesture, the movement, of the congregation and of the liturgists, would have remained lost to us without them. And certainly, we would not have instituted the period of silence in our service had we not seen silence made profound and aesthetic in many concerts of dance in the sanctuary.41

Setting the Stage for Diversity

It’s true that nearly all the players at Judson were white. Even looking at the many artists outside the core group, few people of color participated at Judson in the early ’60s. One of them was Rudy Perez, who grew up in Spanish Harlem; he participated as a dancer/choreographer from the first concert on. The jazz pianist Cecil Taylor played for a dance by Fred Herko. Later in the ’60s, Japan-born Suzushi Hanayagi was active, and Black composer/critic Carman Moore worked with Elaine Summers often.

As it happened, the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater had burst on the scene in 1958 and was already getting international touring while JDT was still under the radar. The Ailey gave Black dance artists opportunities in what is now considered a mainstream aesthetic—and it could pay. There was little crossover between the Cunningham/Judson world and the Ailey world. Gus Solomons jr in the ’60s, Blondell Cummings and Ulysses Dove in the ’70s, and Bill T. Jones in the ’80s, might have been the only New Yorkers who chose to participate in both the Black and white modern dance communities.

I believe that, in their openness and frankness—not pretending to be royalty or Greek heroines—the Judson dancers created an environment that welcomed difference. Rainer noted that “Cage’s notions about democratizing art helped pave the way to the airing of all those issues around race, gender, sexuality, and class that have since burst through the palace gates of high white culture.”42

As we were reminded by “Danspace Platform 2012: Parallels,” it took Ishmael Houston-Jones to step into the breach in terms of race. His original Parallels in Black series in 1982 made a strong statement by bringing African American dancers into the postmodern fold of Danspace Project. Just as Judson Memorial Church opened its doors to a band of renegades who defied the rules of modern dance in 1962, Danspace Project at St. Mark’s Church opened its doors to a band of unconventional Black dancers twenty years later.

And the End of Judson?

The numbered concerts of Judson Dance Theater ended at #16 in April 1964. Jill Johnston wrote, “Their revolution, in its original delirium of a sprawling rebellion, is over. It all happened at Judson Memorial Church 1962–1964…In retrospect, it was a beautiful mess.43

After the numbered concerts, a new bunch of interesting young choreographers, including Kenneth King, Meredith Monk, Phoebe Neville, and Twyla Tharp, found their way to Judson. And slightly older dance artists, like James Waring and Aileen Passloff, who had influenced the Judson group, began mounting shows at the Church. These were often under the name Judson Dance Theater, which is why it’s confusing as to when JDT ended.

On the occasion of Baryshnikov’s Past Forward tour, Allen Hughes interviewed some of the Judsonites about their experiences, including how it ended.

Rainer felt that when the collective workshops held in the church basement stopped, that was the end of the group. Trisha Brown felt it had to do with the dancers wanting to go out on their own as choreographers. She said that the “free-spirited, free-wheeling, mad dash for information and discovery” of early Judson inevitably gave way to “thoughts of separate identities and separate careers.”

Although JDT itself ended in the 60s, the nucleus of it grew into the many-faceted phenomenon of postmodern dance—or post-Cunningham dance, to use the term that Paxton prefers. It is this spirit of experimentation that is carried forth by Danspace Project, Movement Research, New York Live Arts,44 Chez Bushwick, and countless other spaces in New York and elsewhere that were started by avid dance makers.

NOTES

Historical Essays 2