Dare I say it? From what I am noticing internationally, we are in the midst of a new wave of appreciation for older dancers. At the moment several superstars of dance are crashing the age barrier. But I think it goes beyond those extraordinary artists to dancers who are less well known. This post includes examples of both types, quotes from observers and practitioners, and Pat Catterson’s (somewhat humorous) list of roadblocks for those dancers trying to beat the odds.

First the Superstars

Alessandra Ferri, Wendy Whelan, and Carmen de Lavallade are each totally unique dancers, a world unto themselves, and that is part of the reason their artistry has endured.

Ferri in McGregor’s Woolf Works © ROH, photo by Tristram Kenton

As seen in Martha Clarke’s Cheri, the exquisitely dramatic Ferri, 52, can still transport us from rapturous joy to utter despair. (See Gia Kourlas’ cover story for Dance Magazine from last fall.) And just last month, she performed at Covent Garden as the muse for Wayne McGregor in Woolf Works at The Royal Ballet. For me, as I posted in “Alessandra’s Ferri’s Knowing Body,” the ballet completely relied on Ferri’s ability to create a passionate yet vulnerable protagonist.

At the Joyce in April, Wendy Whelan, 48, danced with all the fullness and thrust she always had in “Restless Creature.” And last weekend, in a Works & Process program at the Guggenheim, she showed a sassy theatricality in Arthur Pita’s Tango that I hadn’t seen before. (In case you aren’t familiar with her glorious dancing, what I wrote about her in my recent tribute to her at Danspace still holds true.)

Brian Schaefer, posting in OUT.com, wrote that Whelan’s age “allowed for greater possibilities in interpreting the relationships and interactions on stage. It also added something soothing and serene to each work—maybe we can call it wisdom.” He went on to say, “Especially in ballet, young love still reigns. But with Restless Creature, Whelan…steps beyond ballet’s suggested expiration date and demonstrates that lifelong curiosity and experience are as valuable artistic tools as pirouettes and penchée.”

Wendy Whelan with Joshua Beamish in Restless Creature, photo © Yi-Chun Wu

The legendary Carmen de Lavallade, at 83, knocked ’em dead at Jacob’s Pillow last year in her show As I Remember It. She also became an object of desire at Huffington Post. Brian Seibert of The New York Times called her dancing terrific. And Erin Bomboy of the Dance Enthusiast described her as “mesmerizing and silky.” NPR also jumped into the Let’s-discover-Carmen act with this segment on her.

Carmen de Lavallade, photo: © 2011 Julieta Cervantes

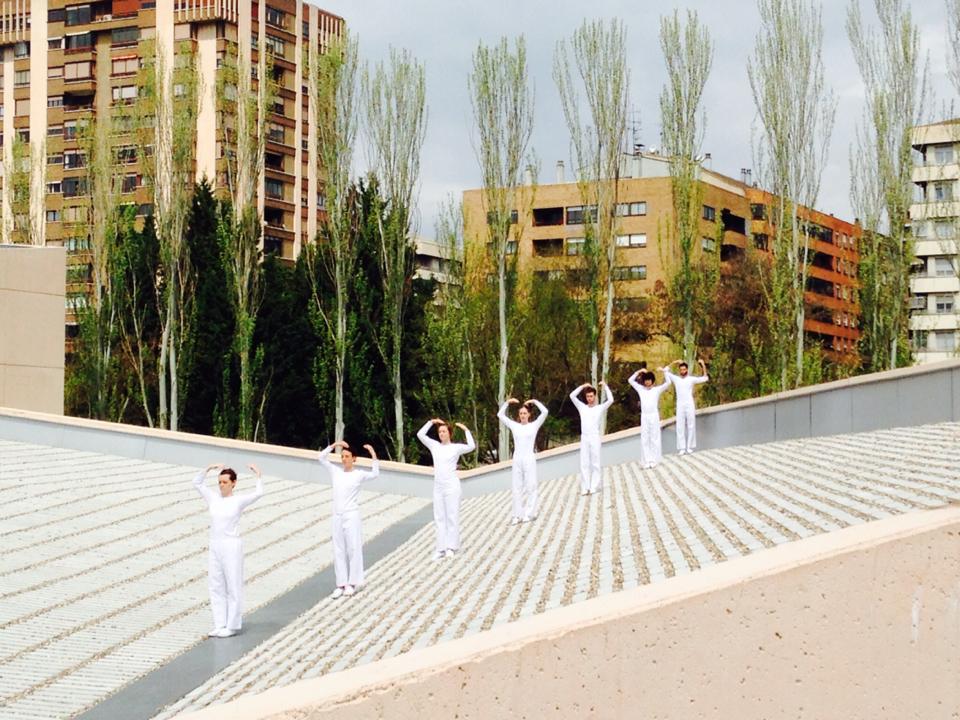

Ageless in Europe

As it happens, venerable superstars of Europe are performing in Rome on June 24 and 25. In a presentation of Daniele Cipriani Entertainment http://www.dancemagazine.com/blogs/admin-admin/6468 the Swedish choreographer Mats Ek and his illustrious wife, Spanish-born Ana Laguna, will perform two of the most sparely poetic works I’ve ever seen: Memory and Potato. He is 70 and she is 60. The program, entitled “Quartet Gala,” also includes well known Tanztheater choreographer Susanne Linke, who turns 71 this month, and Bessie-award-winning Pina Bausch dancer, French-born Dominique Mercy, 65. For more info on the program, which has choreography by Ek, Linke, and Pascal Merighi, click here.

Ana Laguna and Mats Ek in Ek’s Potato, photo © John Ross

Postmodern Forever

Simone Forti at 80 still performs. Though she’s not quite as stable as before, her earthiness and wit are still accessible to her. In an online Fjord Review about Forti’s recent shared performance in Los Angeles, Victoria Looseleaf described her as “Monumental in her simplicity.”

Another historic figure who helped redefine dance in the 1960s, Yvonne Rainer, also 80, brought her premiere Dust to the Museum of Modern Art this month. Rainer supposedly doesn’t dance any longer—though she slipped in a quick chassé and a hovering relevé during the June 13th performance. In an advance story in The New York Times, Siobhan Burke quoted Rainer saying, “My preferred mode of self-presentation is ‘existence.’ I love to exist on stage. I no longer ‘dance.’ ” Later in the article Rainer claimed a right for the aging dancer to exist without judgment: “The aging body is a thing unto itself and need not be judged as inadequate or inferior if it can no longer jump through hoops.”

Stephan Koplowitz and Heather Ehlers in Connor’s The Weather in the Room, photo © Scott Groller

Choreographer Colin Connor cast two dancers over 50 for his work The Weather in a Room that premiered at CalArts last year. They were faculty members Stephan Koplowitz (dean of the School of Dance) and Heather Ehlers (of the School of Theater). He believes in age diversity onstage. Partly because, like Schaefer, he is interested in the relationships that older dancers can inhabit. “In our time,” he wrote in an email to me, “dance tends toward youth, to newness, and to the illustration of things youthful. Here I was drawn to the idea of a relationship that is not new but lived in, to a landscape of ongoing experience and the expressiveness of maturity, and to revealing a palpable physical intimacy between people of an age where this is less noticed or considered.”

Another choreographer interested in age diversity is Vicky Shick, who at 62 still dances in her own work. I happen to be on the receiving end of her largesse and have performed in two of her recent pieces. We’ve danced in each other’s work before so she knows my body and won’t overextend. In rehearsals, I loll around, slowly warming up my body, while she works with the other dancers until it’s my turn.

And just last week I participated in American Dance Guild’s tribute to Frances Alenikoff, who danced into her 80s. I am 67, and my dancing partners were Deborah Jowitt, 81, and Ze’eva Cohen, 75. On performance days, I would go through my daily exercises more thoroughly and add extra time for balancing on one leg. I widened the stance of some of the moves in an effort to be more stable. In performance, I sometimes had the thought, Whew, I got through that bit without keeling over!

Nothing New

Of course the interest in older performers is nothing new. Liz Lerman started using older people in her dances in the 1970s; the Dance Exchange in Takoma Park, MD, carries on her tradition in some of its programs. Choreographers like Stephan Koplowitz and Risa Jaroslow have chosen to work with older performers. Naomi Goldberg’s currently active Dances for Variable Population gives performances and workshops throughout the summer. These kinds of explorations ask the question, Who gets to dance?

Almost twenty years ago Gus Solomons, along with Carmen de Lavallade and the late Dudley Williams, started Paradigm Dance Company, which challenged choreographers like Dwight Rhoden and Kate Weare to make work for these storied but limited performers. Valda Setterfield, 80, whose stage charisma grows with each decade, has danced with Paradigm as well as with her husband David Gordon.

Between This World and the Next

When I wrote about older dancers for The New York Times 15 years ago, I quoted Eiko Otake saying, “Because their bodies are not young, older performers carry something that is almost between this world and the next, that itself is artistic and transcending.’”

Eiko in A Body in a Station, photo © William Johnston

Now in her early 60s, Eiko has been illustrating that idea with her haunting current project, A Body in a Station.

About a year ago, I was fortunate to see butoh artist Ko Murobushi in Yokohama, who embodied a certain brute strength as a man in his late 50s. But this work too, with it’s sudden falls and its offering of lilies, hinted at death.

Alternative Vision

To return to Rainer, she sees the acceptance of age as an “alternative vision.” Here’s an excerpt from an essay she wrote last year for Performance Art Journal (PAJ 106):

“The evolution of the aging body in dance fulfills the earliest aspirations of my 1960s peers and colleagues who tore down the palace gates of high culture to admit a rabble of alternative visions and options. Silence, noise, walking, running, detritus—all undermined prevailing standards of monumentality, beauty, grace, professionalism, and the heroic.”

PatCat’s Nine Lives, or, How to Dance Full Out at 69

But maybe older dancers are a new kind of heroic. Enter Pat Catterson, a dancer/choreographer/teacher who dances full out as a member of Rainer’s group—at 69 years old. (The other members are not far behind: they are all over 40.) She never stopped taking daily class. I asked her to tell me the hardest thing about keeping her body in dancing shape, and she came up with nine hardest things. The rest of this post is direct from Pat Catterson’s lips—or rather email.

From left: Yvonne Rainer, Pat Catterson, Patricia Hoffbauer, and Keith Sabado in Dust at MoMA. Rousseau’s painting of The Sleeping Gypsy is in background, photo © Julieta Cervantes

1. It is difficult to walk the fine line between challenging my body and not overdoing. I can so easily inflame something if I do too much repetition or work past muscle fatigue or not give myself enough recuperation time. When to push and when not is hard to gauge. And the balance is always changing. What I could do two years ago in terms of endurance, I cannot do now.

2. Doctors are dismissive. Oh it is arthritis they say and treat me like I am some kind of crazy person who thinks she can still dance. I try to convince them that I take full class six days a week and am performing and intend to continue but most of them do not take me seriously. It infuriates me. But then I wonder if I am a fool. I find physical therapists more encouraging and helpful than doctors.

3. My brain does not work as quickly as it used to. One of my strengths was always that I picked up quickly. I got the steps fast and often led across the floor. It may not be noticeable to others but I do not pick up as fast now and I have to work at it. Sometimes just as we are to begin a combination, my mind goes blank and I cannot even remember how it starts. The brain does age.

4. I am ignored when I take class. I am used to it now. I am very self-disciplined but I could use a correction now and then, an outside eye. (An exception: Rachel List always gives me corrections.) It is really strange to feel so invisible. And it makes me a little angry, frankly. I am paying for the class like everyone else!

5. I need to rent some ballon! I still could do convincing jumps one year ago but then it ended. I am in shape and I jump every day but I do not go up! I am strong. I stretch. I practice jumping. But the ballon disappeared! I still love leaps and jumping steps anyway even though I look quite unimpressive doing them.

6. My joints are stiff, particularly in my hips. It is very hard to get up and down from the floor. I can only do it in certain pathways. I try to cover it up as best I can by the choices I make. The body just does not fold easily in the joints anymore. Grand plié is now not so grand. Annoying. I am so envious of the ease of the others as I struggle to do things that used to be so easy.

7. Dance clothes. Clingy does not look good on saggy skin! I am bony and I have muscle tone but the skin is saggy. I cannot wear the biketards or the skin-baring tops or leotards the others wear in the summer. I want to wear something sleek and contemporary looking but most regular dancewear just looks ridiculous on me. My age group is not the focus of dancewear companies.

8. In class, I used to love just barreling into everything but that is not possible now. I usually start a big or fast combination a little under in energy to pattern it first in my body so that I don’t strain myself. I can build up to a good energy but I have to start soft. I look at the young ’uns and I remember well that agility and energy. But I do take the full class. Use it or lose it as they say. I try to push past what feels completely comfortable, but just how much is a continual negotiation. Friends who are in their 40s or 50s think I am crazy to continue to take full class, especially Cunningham technique. One says that Cunningham is for young bodies and that I shouldn’t be putting my body through it. But it is my “home” technique and I love the physical and mental challenge of it.

9. In the end I love to dance and perform as much as I always did. The adrenaline of performing still carries me beyond what I think I can do. I have a lot of energy, but I do not want to end up crippled or in a wheelchair. I have to be able to know when to stop demanding too much of my body. And only I will know because the doctors do not know.

Featured Uncategorized 20