Lincoln Kirstein (1907–1996) was a remarkable man, a champion of American art as well as a purveyor of classical ballet. A Diaghilev of his time, he was an impresario, curator, patron, and more than that—a brilliant writer. In the current exhibit at the Museum of Modern Art, Lincoln Kirstein’s Modern, many of his accomplishments are on view: He helped develop the Museum of Modern Art’s collection; he wrote the scenarios and produced some of the first American-themed ballets; he co-founded the School of American Ballet and New York City Ballet with George Balanchine; and he was an early advocate for photography as art.

Kirstein c. 1948, photo by George Platt Lynes, MoMA

Behind the scenes he helped jump-start Dance Theatre of Harlem by procuring major funding; he brought budding choreographer David Vaughan over from England (who became a beacon for dance archivists); he founded the scholarly publication Dance Index (1942–49). He also marched in Selma during the Civil Rights movement, protested the war in Vietnam, and aligned himself with other social justice movements.

But one of his endeavors that is not on display, either in the galleries or in the catalogue, is his long and nasty crusade against modern dance.

As the wall text at MoMA states, Kirstein had “omnivorous interests.” Early on, modern dance, which he sometime called free-form dance, had been one of those interests. He was “magnetized” (his word) by Martha Graham and they became good friends in the mid-30s. He called her “one of America’s greatest artists” and waxed eloquent about her choreography. In a 1937 article he wrote, “She has created a kind of candid, sweeping and wind-worn liberty for her individual expression at once beautiful and useful, like a piece of exquisitely realized Shaker furniture or homespun clothing.” In 1942, Kirstein devoted the first issue of his Dance Index to Isadora Duncan. (This edition is on display at MoMA.)

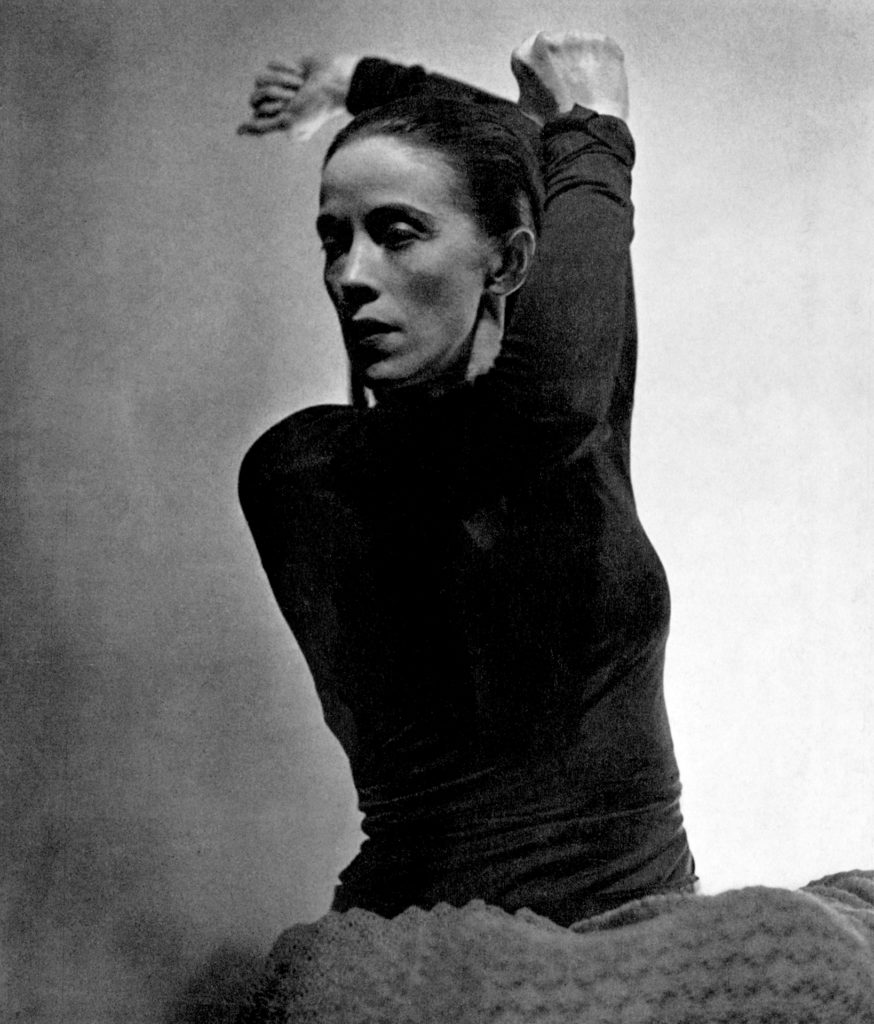

Graham in Chronicle (1936) Courtesy Martha Graham Resources

Sometimes, however, these interests turned into targets for Kirstein’s shooting practice. In a 1986 tirade in The New York Times titled “The Curse of Isadora,” he wrote that while ballet is “a three-ring circus; free-form dance is a side-show with its oddballs, freaks and phonies.” The same year, in an interview in The New Yorker, he said that the post-Graham dance artists either glommed onto ballet (e. g. Tharp) or were minimalist, in which case “There is nothing to look at.” Further, he claimed that “there was never any interest in training children” among modern dancers. The ignorance, voiced authoritatively, is quite stunning.

Although Kirstein invited Martha Graham to collaborate with Balanchine on Episodes (1959), he said privately that he did so because it was “politically useful.”

At a meeting with the Ford Foundation in the 1960s, to which several dance companies were invited, he said something like, “All Martha’s works are about elimination. She dances about shit.” (This was an out-loud variation of what he’d written in his diary after his first view of Graham in 1931: that her work was “a cross between shitting and belching.” But this particular quote comes direct from a recent conversation with former Graham dancer Stuart Hodes.) You could guess how much money the Graham company was awarded as a result of that meeting.

Kirstein’s contempt for modern dance was not a fluke. He’s part of a lineage, a tradition if you will, in the ballet world of throwing shade on modern dance. Michel Fokine had referred to Graham and Harald Kreutzberg as “the horror.” (This is not hard for me to believe. As a teenager, I showed my ballet teacher, Irine Fokine, Michel’s niece, a brochure from the concert I’d seen the night before: a Martha Graham program. She looked at the pictures and said, “How can you like something this ugly?”). The New Yorker critic Arlene Croce, who became a leader of the Balanchine-above-all circle, periodically went slumming and took random potshots at downtown choreographers. She pretty much toed the Kirstein line of celebrating Balanchine ballet while questioning the legitimacy of modern dance.

Walker Evans’ Roadside View, Alabama Coal Area Town. 1936. MoMA. Evans was one of the photographers championed by Kirstein.

In the wall text, MoMA refers to Kirstein’s “expansive view of what art could be.” But this simply did not apply to dance. For him, ballet was the supreme form while modern dance was a passing trend. In his preface to the Balanchine Foundation Catalogue, he calls Balanchine ballets a “paradigm of perfection.” Like the choreographer, he referred to ballet dancers as angels. So lovely, so innocent, so close to heaven. . . So obedient. Balanchine’s steps came mostly from ballet’s codified vocabulary, a.k.a. “the academy,” and the dancers executed these steps. Graham, on the other hand, had the temerity to create her own movements. So, although Kirstein was initially “addicted” to Graham’s work (according to Agnes de Mille), he later denigrated it.

The irony is that Kirstein’s earlier company, Ballet Caravan (1936–1941), had found a warm welcome in the modern dance world. The company debuted at the Bennington School of the Dance (the stronghold of early modern dance), and his booking manager, Frances Hawkins (also Graham’s agent), booked the company into the college circuit laid down by Graham and Doris Humphrey. He favored specifically American themes; according to Sally Banes, he shared with Graham and Humphrey “an urgent search for national identity.” Kirstein himself, in Thirty Years: New York City Ballet, wrote, “In an important sense, Modern Dance may be said to have launched Ballet Caravan.”

Another point made in the wall text at MoMA: When Kirstein traveled to South America to acquire works for MoMA, he was looking for artists who “have attempted to declare independence from traditional European expression.” Of course, this is exactly what Martha Graham was doing: breaking away from European ways of dancing and staking out a distinctively American terrain.

Primitive Mysteries (1931) by Martha Graham. Photo by Barbara Morgan. Courtesy Martha Graham Resources.

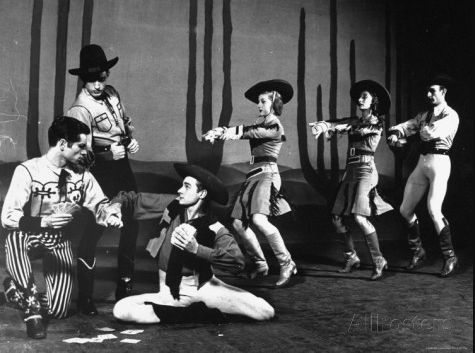

On large screens, the MoMA exhibit shows short clips (shot by Ann Barzel) of several of the ballets Kirstein commissioned for his Ballet Caravan, and they look pretty corny. In Lew Christensen’s Filling Station (1938) and William Dollar’s A Thousand Times Neigh! (made for the Ford Pavilion at the World’s Fair, 1940), the characters are broadly drawn. We see literal, almost pantomimic portrayals, and plots that are often excuses for multiple jumps and turns. To me, these ballets (granted, brief clips without music do not tell the whole story) look like children’s theater. Even Eugene Loring’s Billy the Kid (1938), which did have an afterlife, looks hokey now.

Michael Kidd and John Kriza of ABT in Billy the Kid, 1944.

By contrast, Graham’s works like Chronicle (1936) and Primitive Mysteries (1931) have stood the test of time. The all-women’s group in Chronicle, now being performed at the Joyce by the Martha Graham Dance Company, gathers force as it welds design and emotion together. Each movement, whether rooted or springing upward, is essential to this ode to human power in the face of growing fascism. Graham’s signature works of the 30s broke new ground in the dance wing of modernism, while most of Kirstein’s ballets of the period were insignificant, except for his insistence on using American composers.

Xin Ying in Chronicle, photo by Melissa Sherwood

Considering the artistic flimsiness of Ballet Caravan’s rep, Kirstein’s verbal darts aimed at Graham were not only cruel but preposterous.

Regarding other modern dance figures, Kirstein was hardly more charitable than he was with Graham. When he invited Merce Cunningham to choreograph for Ballet Society (the precursor to NYCB) in 1947, he was ready with clever put downs for Cunningham and John Cage, who wrote the score: He called them “minor anarchs.” Not surprisingly, he also had words for Alvin Ailey (“tasteless vitality”).

To put these put-downs in context, he flip-flopped on many people in the arts, applying superlatives one week and degrading remarks the next. (This was true of his treatment of ballet icons Arthur Mitchell and Jerome Robbins as well as of Duncan, Graham, and Cunningham.) Diagnosed with manic-depression, Kirstein was first institutionalized in 1967. Martin Duberman, his biographer, even implies that his more outrageous slurs were caused by manic phasees. Jacques d’Amboise describes occasions when Kirstein viciously insulted an artist soon after praising him or her. (The way d’Amboise tells it, these tales of Kirstein’s uncontrollably boomeranging opinions can be very funny.) I sometimes think that most of the ballet world considers it rude, or at least indelicate, to point out the unhinged ravings of such a respected figure. But these “fulminations,” to use Sally Banes’ term, had damaging effects, and one of them was to deny funding to modern dance. Another was, as I’ve mentioned, to give permission to treat modern dance as an inferior art form.

Today ballet and modern dance are less polarized. One of the qualities of the latter that most appalled Kirstein—the earthbound mode (as opposed to the airiness/loftiness of ballet)—has seeped into the work of current ballet makers. For both Justin Peck (NYCB resident choreographer) and Alexei Ratmansky (artist in residence at American Ballet Theatre), the floor sometimes exerts a magnetic pull. Another sign of the closer relationship between the two genres is that, in this centennial year of Cunningham, the master’s works are being performed by companies like Ballet West and The Washington Ballet. And of course, it’s thrilling that NYCB invited (post)modern dance artist Kyle Abraham to contribute to its repertory—and that The Runaway, with music by Kanye West and Jay-Z, was such a runaway hit.

But there is still a privileging of ballet that pervades dance training, performances, and criticism. Perpetuating that hierarchy, The New Yorker has just appointed Jennifer Homans as its new dance critic. Homans, author of Apollo’s Angels (meaning of course, Balanchine’s dancers), has established the Center for Ballet and the Arts, a well-funded project at NYU that announces the primacy of ballet in its very title. And so the privileging continues.

Sources:

• Lincoln Kirstein’s Modern, MoMA exhibit.

• The Worlds of Lincoln Kirstein, by Martin Duberman.

• By With To & From: A Lincoln Kirstein Reader.

• Ballet: Bias and Belief, Three Pamphlets Collected and Other Dance Writing of Lincoln Kirstein, Dance Horizons, 1983.

• I Was a Dancer, by Jacques d’Amboise.

• “Lincoln Kirstein, Modern Dance, and the Left: The Genesis of an American Ballet,” by Lynn Garafola, Dance Research Journal, v. 23, no. 1, Summer 2005.

• “The Curse of Isadora,” by Lincoln Kirstein, The New York Times Archives, Sunday, Nov. 23, 1986.

• “Profiles: Conversations with Kirstein — 1,” interview with W. McNeil Lowry, The New Yorker, Dec. 15, 1986.

• “Sibling Rivalry: The New York City Ballet and Modern Dance,” by Sally Banes, in Dance for a City: Fifty Years of New York City Ballet, edited by Lynn Garafola with Eric Foner.