I thought I knew about Sylvia Waters’ long life on the Ailey planet, but when she spoke recently on a panel celebrating 90 years of dance at the 92nd Street Y, I heard some surprises.

I knew she’d attended Juilliard because Sylvia and Pina Bausch received Dance Magazine Awards the same year—2008—and they reminisced a little bit about their times at Juilliard together. In fact, I quoted Sylvia when I wrote my opus on Pina Bausch at Juilliard and NYC because she had such a clear view of Pina’s talent back in 1960.

I knew that Sylvia had danced with Ailey for seven years, then led Ailey II for thirty-eight years, from 1975 to 2012.

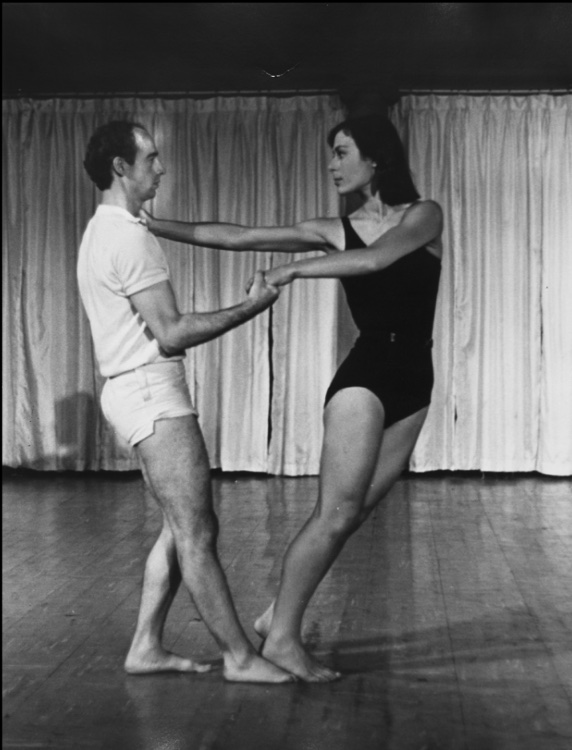

But she had a full dance life before joining Ailey. As a teenager she was studying at the New Dance Group on scholarship, taking class with Bill Bales and others from that period. Then, one day, when she was 14, she had a substitute teacher for Horton technique—and that turned out to be Alvin Ailey. Later, at Juilliard, her Graham teachers were Helen McGehee, Mary Hinkson, Bert Ross, and Ethel Winters.

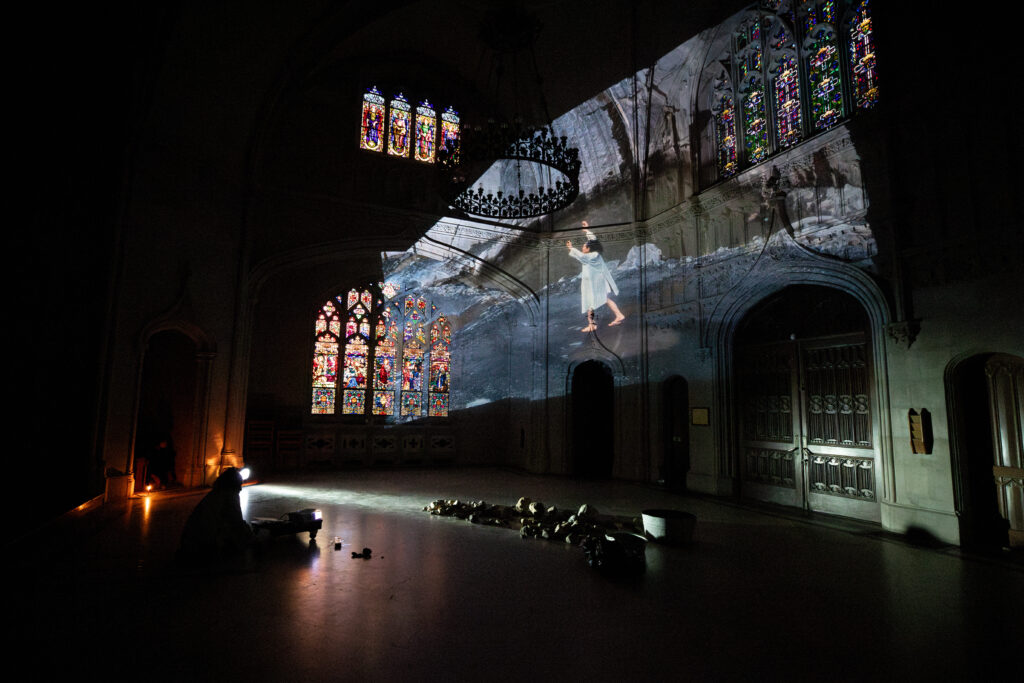

When she saw Ailey’s Blues Suite during his debut at the 92s Street Y in 1958, she felt a strong connection. In this Ailey Up Close video, introduced by Robert Battle, Sylvia says, “I really had a visceral reaction to it…I was very familiar with these characters, and I was familiar with Blues music.” She admired the dignity and energy of the characters. However, she didn’t dance with Ailey until ten years later.

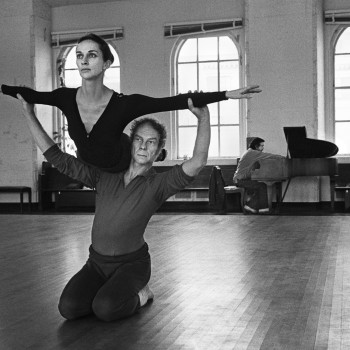

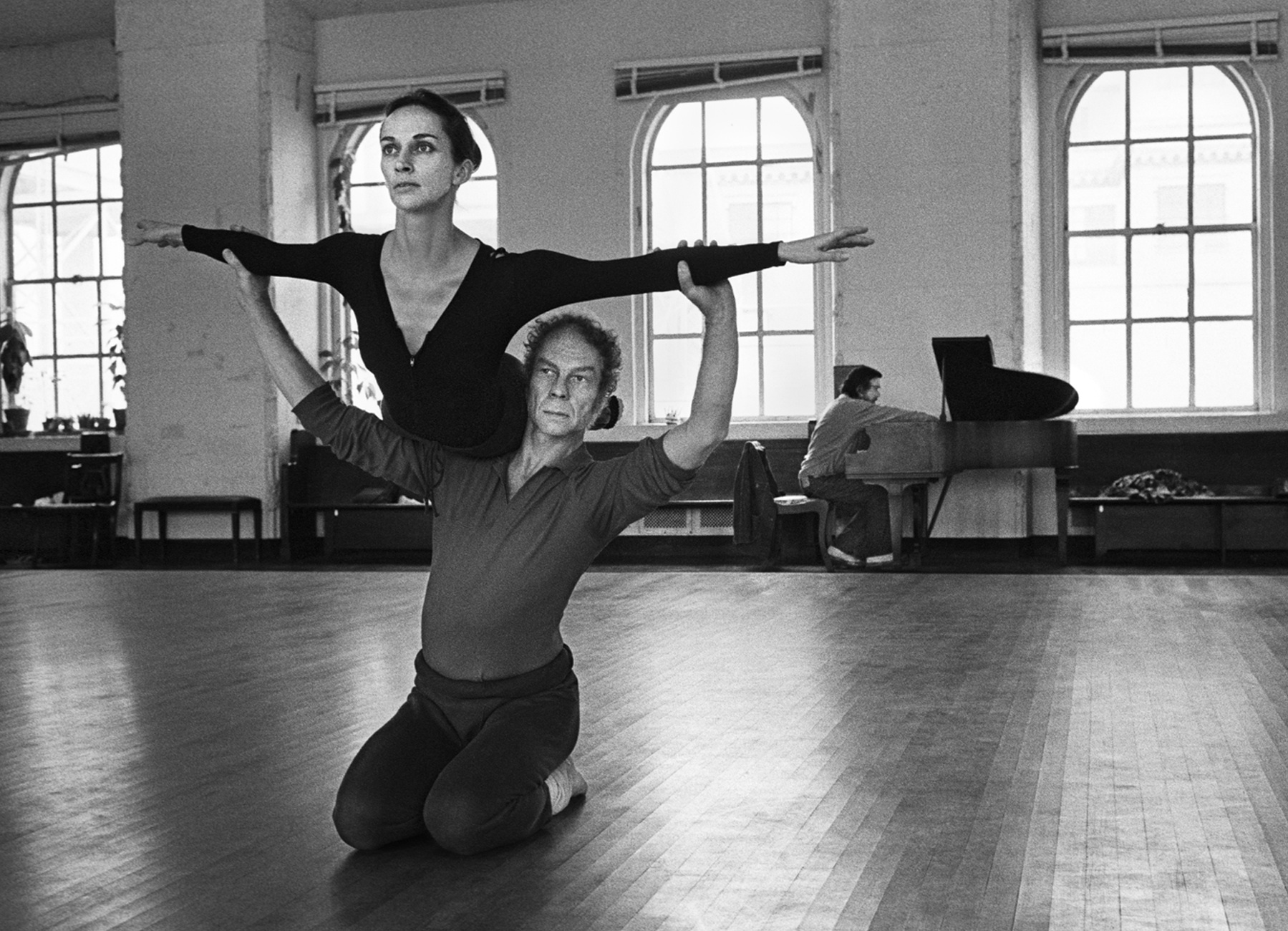

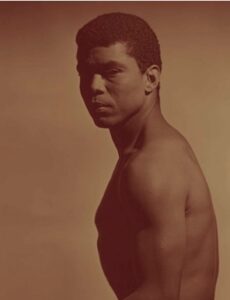

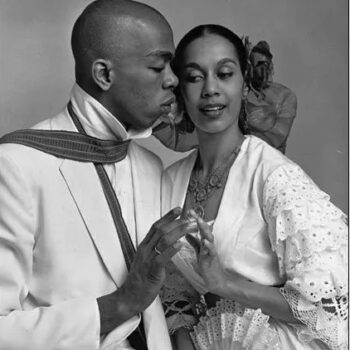

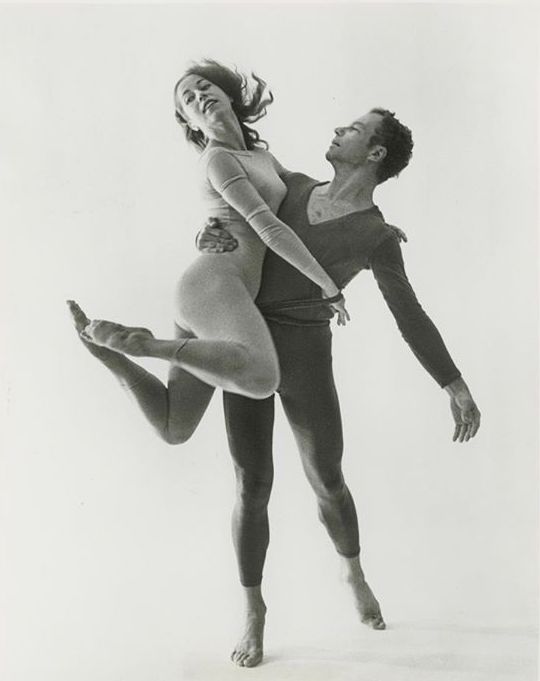

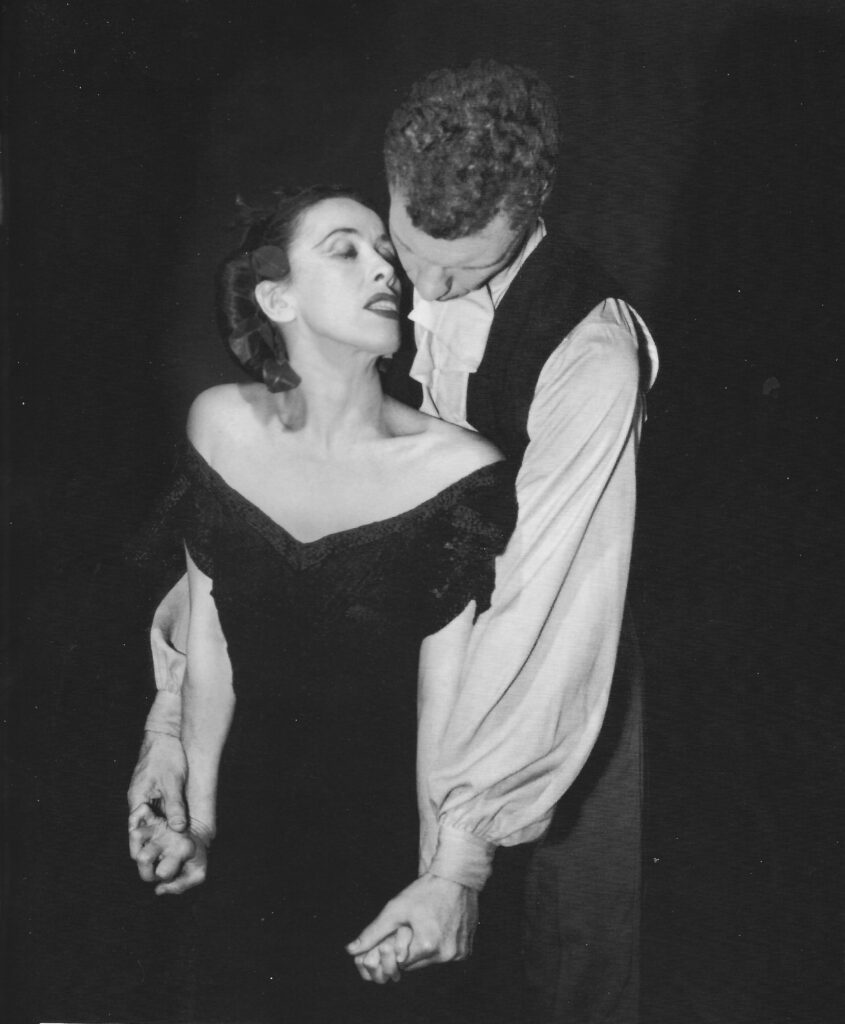

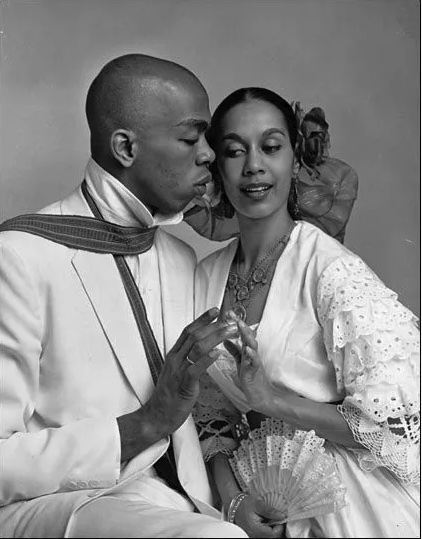

In 1960 Donald McKayle asked her to perform in what he called his “epic” work, They Called Her Moses, about Harriet Tubman and the Underground Railroad. It was being remounted for CBS television’s Camera Three in 1961. The star-studded cast included Arthur Mitchell, Carmen de Lavallade and Graham dancer Robert Powell. Thanks to Walter Rutledge, this bit of amazing history is posted here. Sylvia plays a poignant figure, and her energy jumps off the screen. Her part is preceded by a duet for Arthur Mitchell and Kathleen Stanford, and followed by a gorgeous duet for Donald McKayle and Carmen de Lavallade as young lovers hoping for a better life.

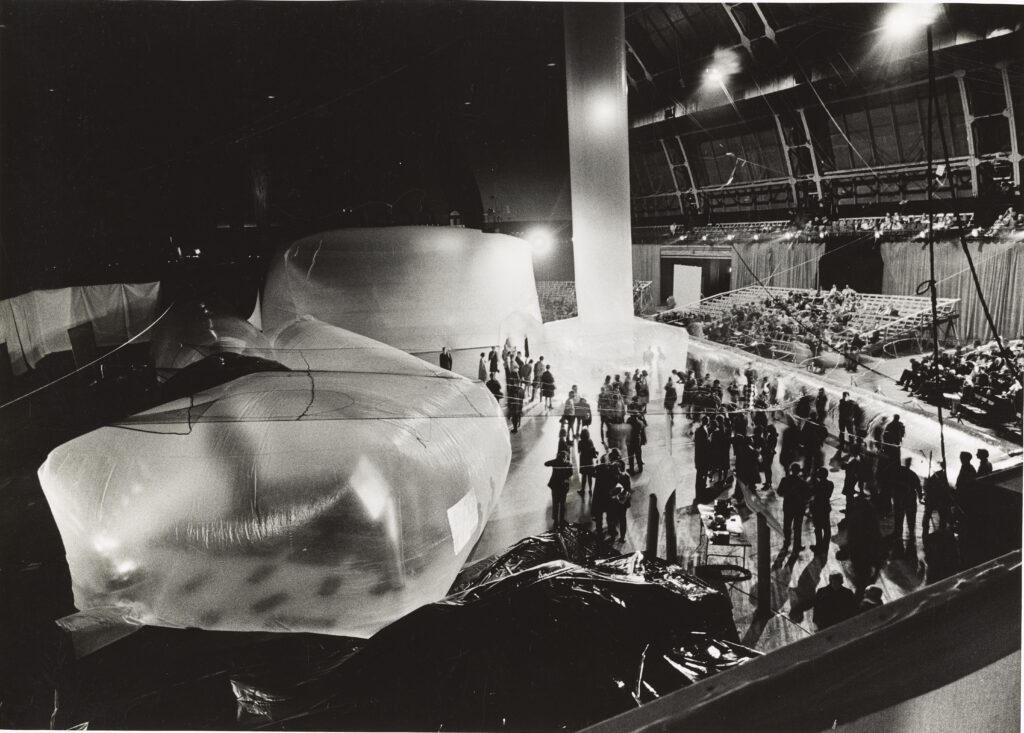

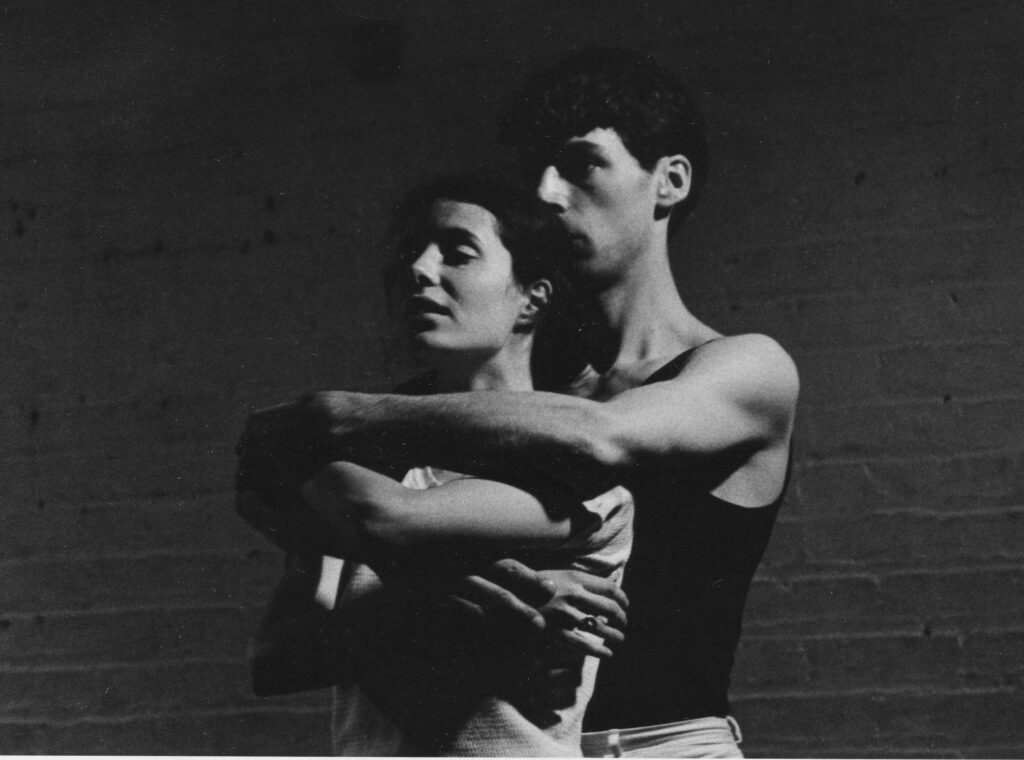

The first time Sylvia danced at the Y, it was with Hava Kohav, whom she undoubtedly knew from Juilliard, in 1961. Other Juilliard dancers in that group were Dudley Williams, Bill Louther, and Mabel Robinson. (Hava Kohav Beller went on to become a filmmaker.) Sylvia then went to Europe, where she worked with Maurice Béjart. In 1965, when Sylvia saw Revelations, she said to herself, “That’s where I want to be.” But it didn’t happen until 1968, when she ran into Alvin Ailey at BAM while attending a performance of Martha Graham. He asked her “What are you doing,” and that was the beginning of her forty-five years with Ailey.

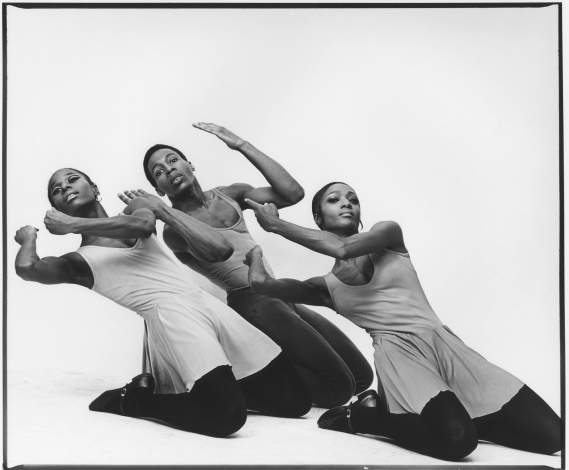

As longtime leader of Ailey II, Sylvia nurtured young dancers, gave opportunities to choreographers, arranged tours, and chose the rep. When she stepped down in 2012, she said in Dance Magazine, “I believe in renewal; I believe in change.” In this article in the NY Times, Gia Kourlas says that “Ms. Waters’ track record of spotting talent is astounding.”

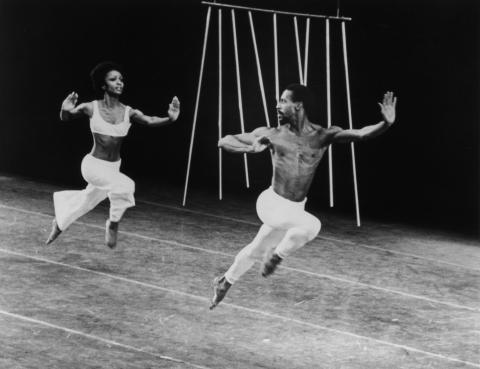

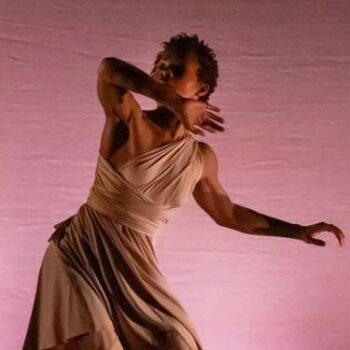

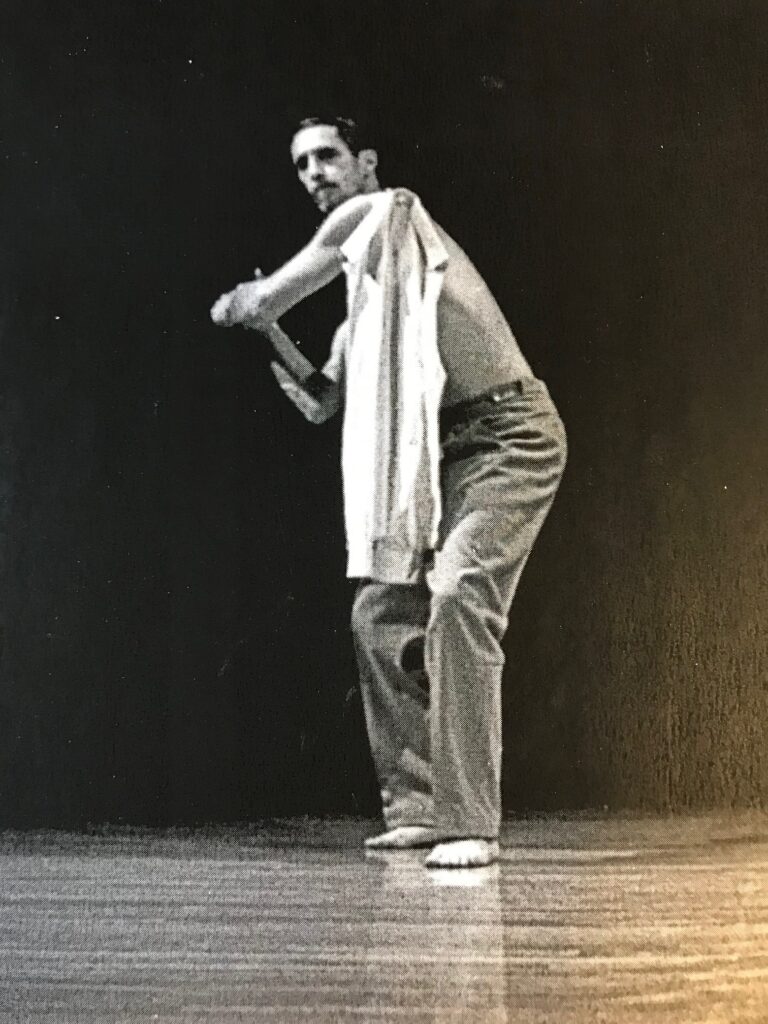

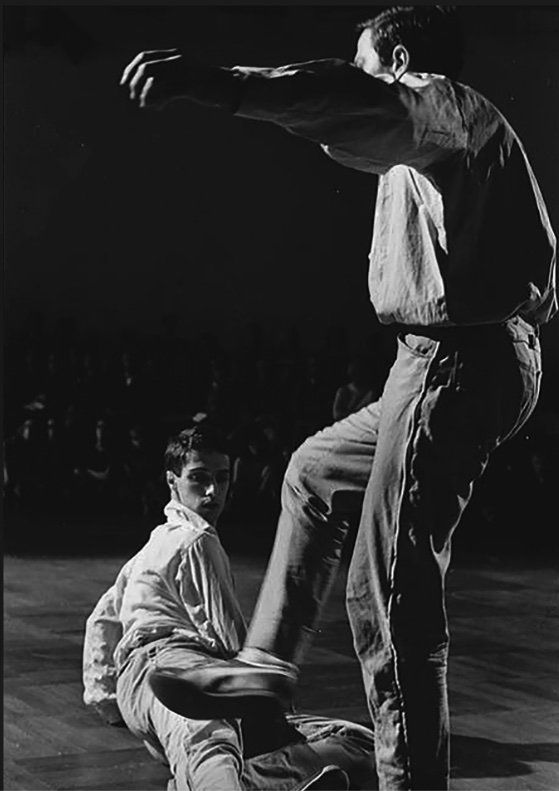

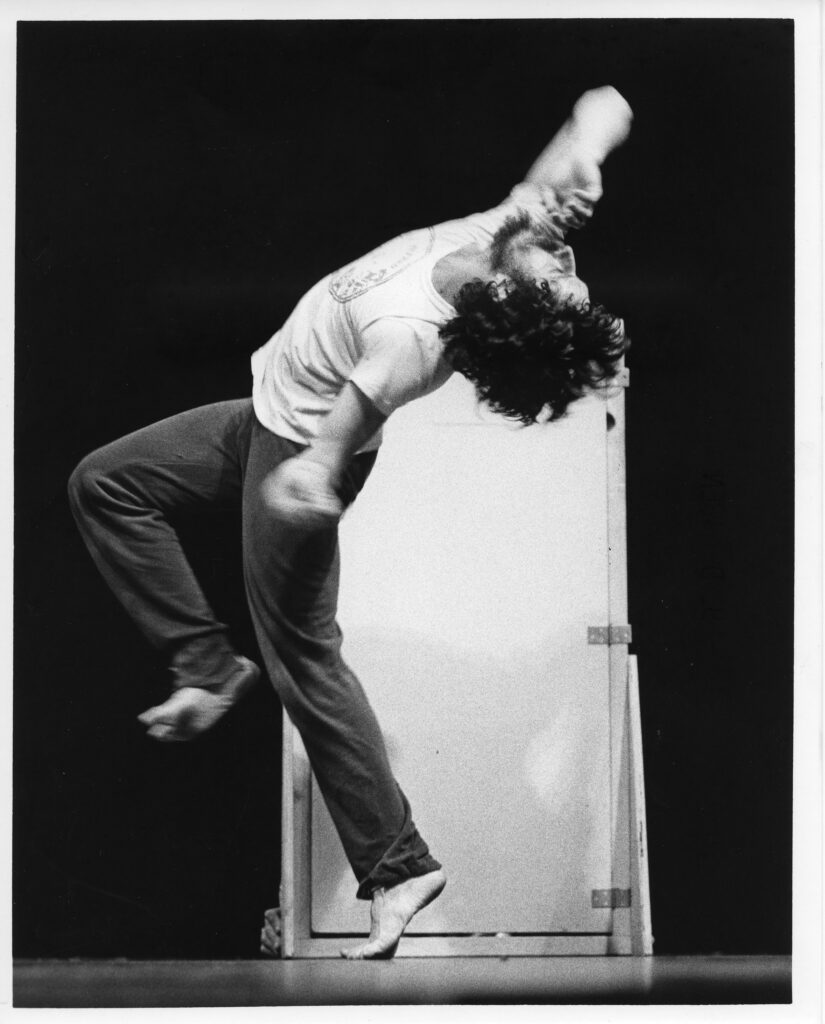

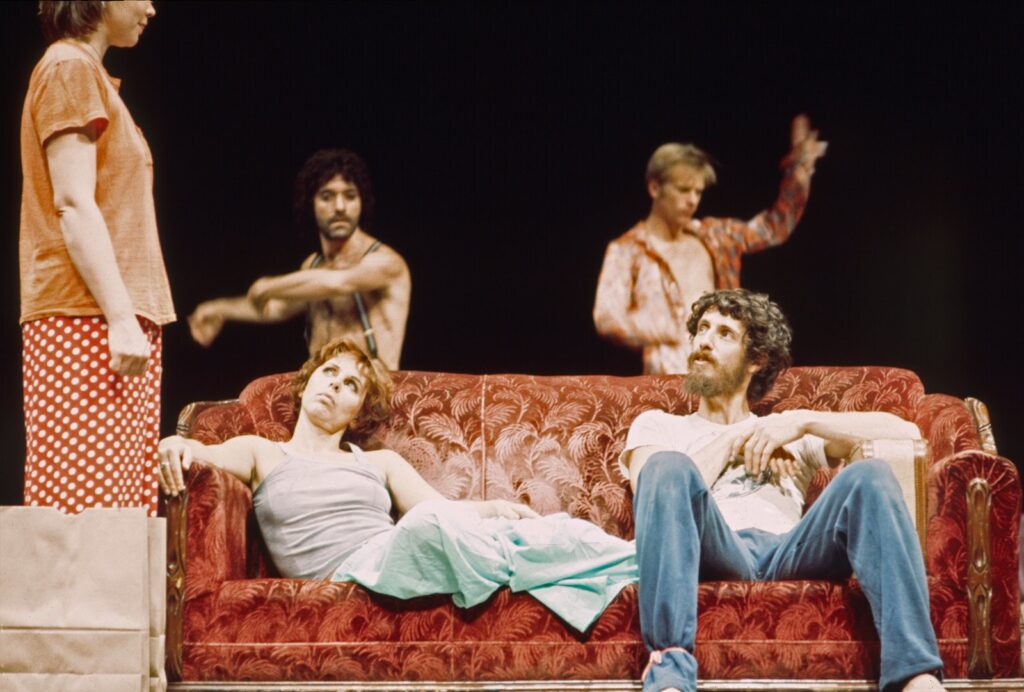

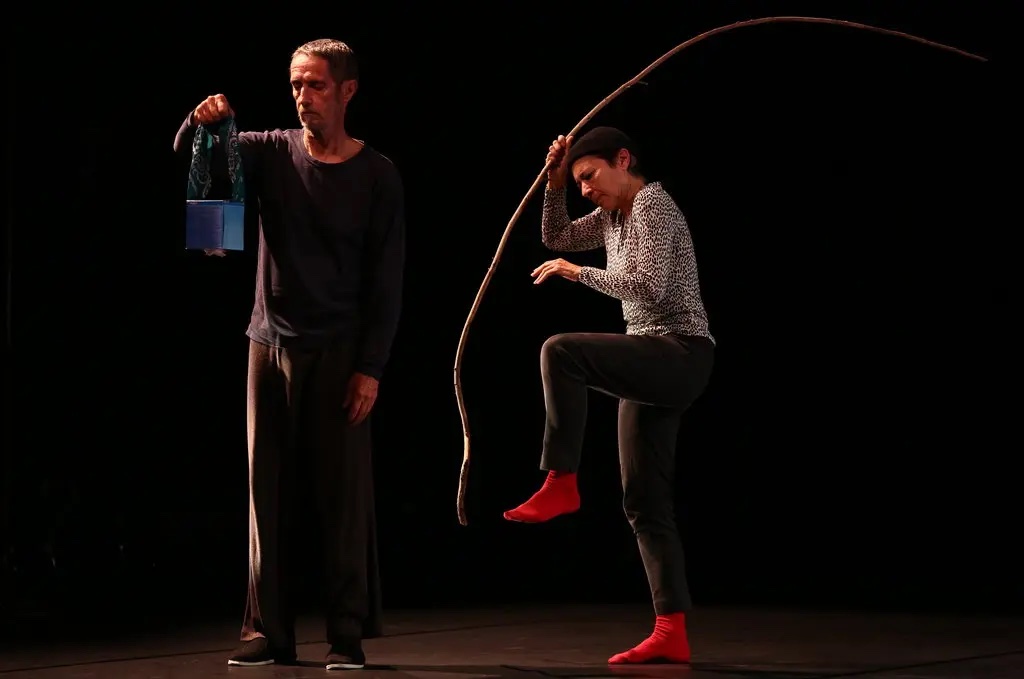

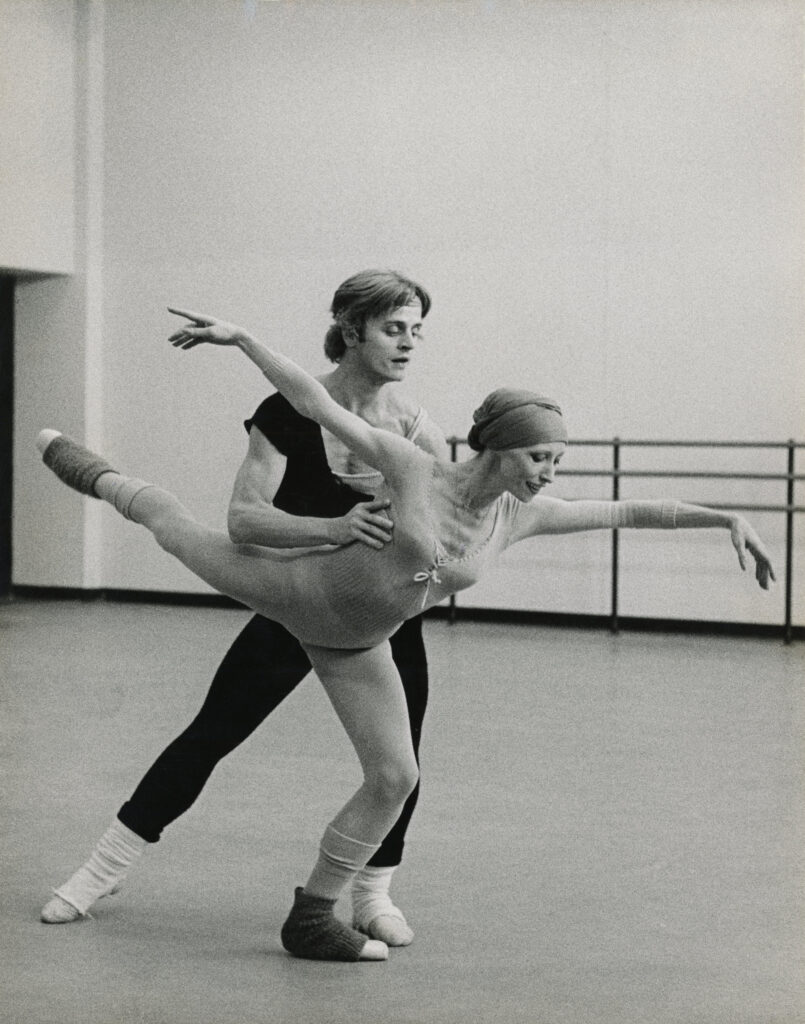

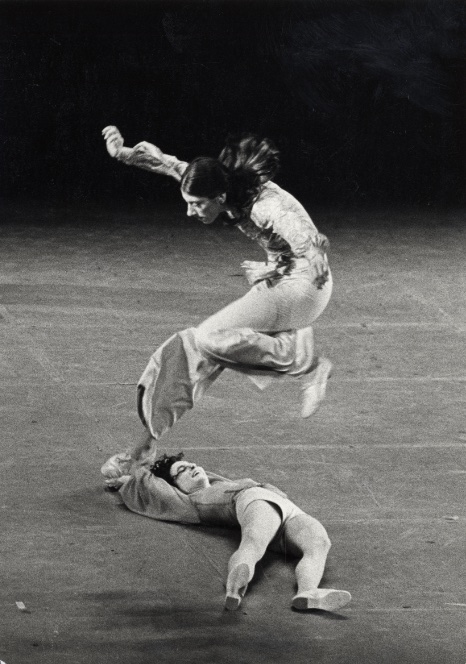

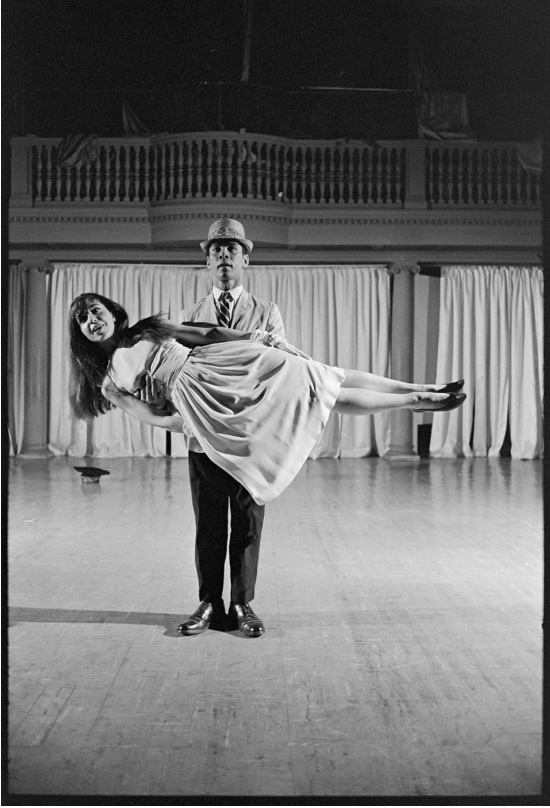

Alma Woolsey, Danny Strayhorn, & Sylvia in The Road of Phoebe Snow by Talley Beatty, 1969, Ph Jack Mitchell

In addition to the Dance Magazine Award, she received an honorary doctorate from the SUNY Oswego, a Legacy Award as part of the 20th Annual IABD Festival, the Syracuse University’s Women of Distinction Award, and a “Bessie” Award.

Currently, Sylvia leads The Ailey Legacy Residency for college-level students. Last year, she created Portrait of Ailey, an eight-part documentary series for PBS LearningMedia for Black History Month, a website with classroom-ready resources for pre-K-12 teachers.

I love it when one woman’s passion and integrity take her on a long path that enriches us all.

Featured Leave a comment