On the occasion of get dancing being nominated for a Bessie, I wanted to say why this evening, by Catherine Galasso and Andy de Groat, prompted thoughts and reveries. Well, now it turns out that it won’t actually win a Bessie (the revivals category winner has already been announced, pre-event). So I will just thank the Bessie committee for the nudge and go ahead with these thoughts anyway.

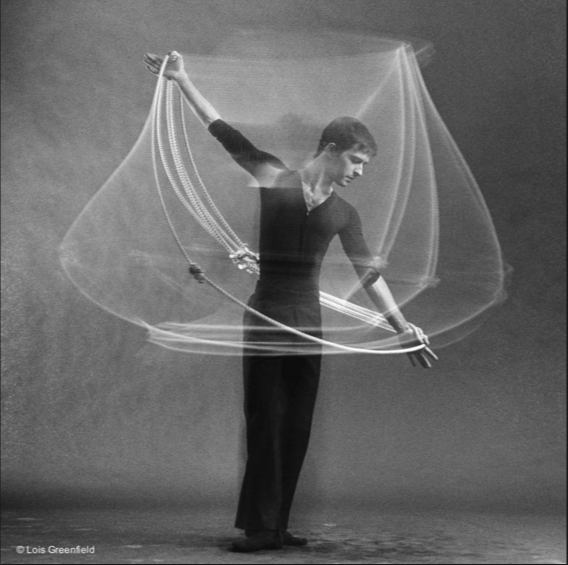

Andy de Groat in Rope Dance Translations, late 1970s, photo © Lois Greenfield

The evening, a combination of reconstructions of Andy de Groat’s work and a new work by Catherine Galssso, captured something elusive about the ’70s. The only way I can describe it is that things at that time were unforced. There was a sense that people were finding ways to let choreography happen rather than willing it to happen. This was reflected in all parts of her program last December at Danspace Project, St. Mark’s Church. Catherine’s new piece, notes on de groat, was in tune with that spirit but with an added dose of athletic energy. The experience was like following a string back through time and finding some sort of treasure. What she found wasn’t flashy or transgressive, but an enchanted meeting of movement and music, so different from the high-concept or technology-laden performances I sometimes see today.

Catherine Galasso, photo by Jacob Burckhardt

Catherine Galasso’s father, Michael Galasso, was a composer of such intriguing, beautiful music that I’m surprised it hasn’t been used by more choreographers. He died in 2009, and get dancing is his daughter’s collaboration with de Groat, the choreographer most associated with his music. They worked together in the ’70s, at first under the direction of Robert Wilson. This was before the days of the Joyce and BAM’s Next Wave Festival, when downtown choreographers weren’t thinking in terms of proscenium. Andy was a regular at Danspace, where lighting genius Carol Mullins was in residence even back then. Luckily, Mullins, who toured with de Groat before coming to Danspace in 1982, was on hand to light Galasso’s evening too.

The rebuilding of de Groat’s work brought a fresh breeze into Danspace. Simplicity, visual beauty, and the spirituality of minimalism were all there to be savored. The performers ranged from Charles Dennis and Frank Conversano, two heroes of “pedestrian dance” who were in the original works, to current freelance dancers Meg Weeks, Madeline Wilcox, Chris deVita, and Kristopher K.Q. Pourzal.

This project grew from Catherine’s love, curiosity, and a wish for continuity. In a posting on the Danspace website, she says about these works, “I felt that if I didn’t bring them…de Groat’s history with this city might disappear. This is archiving through re-performance. It’s my way of passing this choreographer’s work on to a new generation.”

Film and Reconstruction

The 1979 black-and-white film of Rope Dance Translations, with Michael Galasso’s spiraling violin music, set the tone. Each of the five spinning dancers had a three-strand rope that whipped outward or looped overhead depending on their arm and torso movement. To my eye, they had an affinity with Simone Forti’s 1961 “dance constructions,” wherein the movement and visual objects were inextricably bound. Watching these sculpture-dancers in John Meaney and Andrew Horn’s film, spinning with slight variations in how the rope extended the body, gave a focus to our senses and our thoughts. The union of motion, object, and sound was hypnotic. Toward the end, the two-dimensional film expanded into three dimensions when four dancers stepped into the space for a live rope dance. We had just seen three of them on screen, 36 years younger: Ritty Ann Burchfield, Frank Conversano, and Charles Dennis.

Fan Dance—Good for Mental Health

Michael Galasso’s music for fan dance (1978) is hauntingly beautiful—celestial really. De Groat paired it with purposeful walking and simple gestures, fans in hands. According to Weeks, he had counted the music in an odd way.

“That music is counted in a traditional 4/4 timing, but Andy came up with this really different time signature for it, which was two 4s, two 5s, two 6s, two 7s, two 11s, two 4s, and two 11s. It’s that set repeated four times. The music is this sort of sweeping grandiose music for strings and it’s uplifting. At first the counting sequence was difficult to learn…but after a while I didn’t have to count anymore. It just kind of worked…That dance is really special, I feel like everyone should do it for their mental health.”

fan dance, all current photos by Victoria Sendra

That night in December, I felt my own mental health infused with peace, just watching and listening to it.

get wreck

Another piece, get wreck (1978) had an intergenerational cast. Older dancers like Kathryn Ray, Burchfield, and Conversano, who were part of the original cast, commingled with younger dancers. They all possessed the unmannered, gently energized demeanor necessary for negotiating the complex patterns. At that time, downtown people were challenging the virtuosity of concert dance with pedestrian movements, just as Andy Warhol challenged the ideal of artistic beauty by presenting everyday soup cans as art. The aesthetic of the ordinary permeated much of downtown.

Part of the inspiration for get wreck sprang from artist and wordsmith Christopher Knowles. Sometimes considered autistic in his early years, he started working with Robert Wilson when he was 13. (For a New Yorker article on Knowles click here.) De Groat also worked with Knowles and took the title get wreck from a poem of his that was set to music.

a section of get wreck poem by Christopher Knowles, courtesy Carol Mullins

For Knowles, repetition was about rhythm and pattern. It seemed like he’d get lost in the words and find his way through. Viewers had to pay close attention to perceive each small change—not unlike Trisha Brown’s accumulation series. Knowles figured out his own way of accumulating words.

Bridging Past and Present

Catherine’s new piece is specifically about the process of reconstructing. I usually don’t like dances that explain themselves, but her notes on de groat was done with such clarity, love, and sly wit that it won me over. You felt a tug from the past, but more than that, an exchange with the past.

While Catherine speaks at a microphone, Weeks, deVita, and Pourzal pass through a limited vocabulary of spins, jogs, and crouches with their own personal flair. Reciting her text, the narrator (now switched to Pourzal), says, “This process, while partly about re-creation, is also about how the dancers and I find our own voices within Andy’s aesthetic in an attempt to bridge past and present.”

Pourzal, Weeks, and deVita in notes on de groat

The text, which you can hear in its entirety in this Vimeo, includes passages from her correspondence with de Groat. For instance, she let him know that she didn’t like his idea of starting the evening with the film. “Your proposal for program order is making less and less sense to me,” she wrote. She thought that starting with a long and uninflected film might put people to sleep. She was torn between honoring his wishes and her own theatrical instincts. But in the spirit of cooperation, she told him, “I’m ready to get behind it and will embrace it as an experiment.”

“Catherine,” he wrote back, “life is an experiment….If I was doing what I do for people who zap [change the TV channels quickly], are in a hurry, don’t have time, I would’ve stopped a long time ago…Looking for what is considered success is so totally smoky and subjective as to be dangerous.”

This is kind of a key to that unforced thing. De Groat had a clear progression in mind and refused to force it into a format that might be more convenient for the audiences.

There’s a point, after Andy is quoted saying “Explications can be misleading,” when Galasso’s music surges into circular riffs (a bit like Philip Glass, but the two were contemporaries, not one following the other) that carry the dancers into their next, more rambunctious section. Together the music and dance seem to be saying that they don’t need any explanations.

Repetition Then and Now

In my memory, the use of repetition by New York choreographers during the 70s—de Groat, Laura Dean, Barbara Dilley, Meredith Monk, Trisha Brown, Harry Sheppard (who danced in the original get wreck)—invited viewers into a meditative state of mind.

These days the repetition I see is more like a display of endurance. The energy is often pushed. I admire the stamina of the dancers and the boldness of the choreographic mind behind it, but it makes me wonder, When did the tone of repetition change? Maybe Anne Teresa de Keersmaeker was a transitional figure. Influenced by Trisha Brown and Lucinda Childs, her dancers also have to count a lot, but there’s more force in her repetitions. With her intricate gestures and fierce physicality, she gave repetition a certain drama. And now I’m seeing a trend that’s even more hard-edged—generating drama from sheer stamina.

I am indebted to two dancers from Galasso’s evening for shedding light on this trend. In my phone conversation with Weeks, who also danced with Donna Uchizono, she compared today’s attitude with that of de Groat:

“I feel like an interest in duration today has to do with exhaustion and rendering physical exertion legible to an audience…It’s maybe redefining virtuosity, independent from a ballet context, where virtuosity is defined by the ability to do tricks, obviously stylized and in context. Maybe some of the contemporary interest in examining virtuosity is from a more pedestrian angle.”

Weeks and Pourzal in Fan Dance

Madeline Wilcox performed in the final reconstruction of the get dancing evening. It was an excerpt of de Groat’s Swan Lac, which was the last show de Groat produced in New York before moving to France. The dancers’ aerobic phrases reminded me that by 1982 Andy was speeding up his pacing (the music is the Talking Heads). Wilcox said the cardio workout was the most challenging part of performing it. But she said that, naturally, she has a more complex engagement when she is part of the making process. When talking about her work with current choreographers like Sarah Michelson and Jillian Peña, Wilcox said this:

“It’s more about research of each movement, asking questions inside that movement so that it is fresh every time, even though to the outside eye it might just look like repetition… looking at the complication inside the task of what we’re doing so that it is no longer the old repetition. You work on it for a year and you form an attachment to it.”

The emotional aspect of repetition, for both the dancer and the viewer, can range anywhere from meditation to obsession. I think the tone of it, the timbre, the state of mind it induces, changes according to the heartbeat of the choreographer—and of the times. And the feeling of today’s arts and media is definitely more bombarded, almost under siege, and therefore more forceful in its counterattack. Maybe that’s why the Galasso/de Groat/Galasso evening was such an oasis.

Michael O’Rourke and de Groat in the first Swan Lac, Aix-en-Provence, early 1980s, photo by Christiane Robin

Spinning… in between

In notes on de groat, Catherine describes seeing an archival film of Andy spinning in Iran in 1972, “nonstop, light on his feet, as if floating in the air.” She continues: “Spinning seems strangely transporting, both virtuosic and pedestrian, spiritual without being religious. It so perfectly encapsulates that era…”

And then Catherine quotes Andy: “Spinning and all dance concerns the mind state between waking and sleeping, life and dreams, the conscious and the unconscious. With spinning, all movement is generated from a basic walk around in place, like taking a walk with nowhere to go.”

There is something about that in-between place that means to me an acceptance of where you are. It’s about giving yourself the time to dwell on one thing. And I would translate “nowhere to go” closer to, having nothing to prove.

For Catherine, this project began as a way to enter de Groat’s work and to find a balance between her voice and his. In following her personal quest, she revealed a whole different aesthetic, an aesthetic of task lifted by beautiful music, of circles of the mind, of patience and poetry.

Featured 1