Dance people in China are curious about dance in the West—and it goes both ways. In June, I was a guest engaged in two genres—ballet and modern dance—in two cities—Shanghai and Beijing. I participated in dialogues, gave lectures, directed workshops, and observed classes and rehearsals. I became curious about two dance forms that are largely absent in the United States: Chinese classical dance and dance drama. And a bonus: I saw a very exciting young choreographer. I learned a lot about China through dance—and through the quietly wheeling, arcing traffic at large intersections.

Traveling by wheels

Here is how this double-duty exchange happened. Yuan Yuan Tan, the great Chinese ballerina of San Francisco Ballet, invited me to speak in the forum sponsored by her Tan Yuanyuan Studio. Around the same time, I was re-invited to speak on post-modern dance by Professor Qing-Yi Liu at Shanghai Theatre Academy and Wang Xin at Beijing Dance Academy. The latter two invitations came through Lan-Lan Wang, the tireless Chinese-American dancer/teacher/producer who has organized many China-U.S. exchanges. (In 2017, Lan-Lan had arranged for two of my articles on Trisha Brown to be translated and published in Chinese dance journals.) So this trip expanded into a week in Shanghai and a week in Beijing.

Tan Yuanyuan Studio Forum

Every year, YY’s Studio, under the auspices of Shanghai Theatre Academy, organizes a forum to illuminate dance in some way. This year’s forum presented three events: an evening about John Neumeier’s The Little Mermaid, a dialogue on contemporary choreographers, and a roundtable of local scholars and teachers (plus me) talking about current trends in dance.

During the first evening, I realized what a charismatic speaker YY is. She was in her element—lively, fun, and spontaneous—talking about the challenges of The Little Mermaid. This ballet, based on a Hans Christian Andersen tale and defined by Neumeier as a dance drama, was a turning point for her. It challenged her to dig into herself and find the acting skills to portray the Mermaid. Her recent partner in that ballet is Aaron Robison, the charming British dancer who recently joined SFB. In between film clips of the ballet, YY and Aaron demonstrated the tricky lifts while the Mermaid is swishing her blue satin-y tail—which YY had brought all the way from San Francisco. They described the injuries they incurred—to knees, to rib cage—while working on the ballet. In the film clips you could see how YY used her face to express the Mermaid’s yearning and despair, and let her legs collapse under her to show the pain of learning to locomote on land. She said she had to allow herself to be “ugly,” which to me means letting go of ballet aesthetics to portray an extreme state of feeling. Even on film, her portrayal cut to the heart. As Steven Winn wrote in SF Chronicle, “The masterpiece here is the Little Mermaid herself, brought to heartbreakingly vivid life by Yuan Yuan Tan on opening night. In an absolutely astonishing, emotionally fearless performance, Tan leaves everything on the stage . . . Tan is utterly committed to the emotional truth of the moment.”

Yuan Yuan Tan with Aaron Robison in The Little Mermaid. Photo by Erik Tomasson

The second event was a dialogue between YY and me about contemporary ballet choreographers. I had chosen four who had worked closely with YY: Christopher Wheeldon, Alexei Ratmansky, William Forsythe and Wayne McGregor. I showed some images, described their styles briefly, and asked YY to talk about working with them. Having been a muse for some of these choreographers, she gave us insights about their work. (Sorry, I can’t tell you what she said because, well, she was speaking Chinese. My interpreter was whispering in my ear, but I didn’t catch all of it.)

In dialogue with YY. My interpreter, Brenda Liu, is to my right.

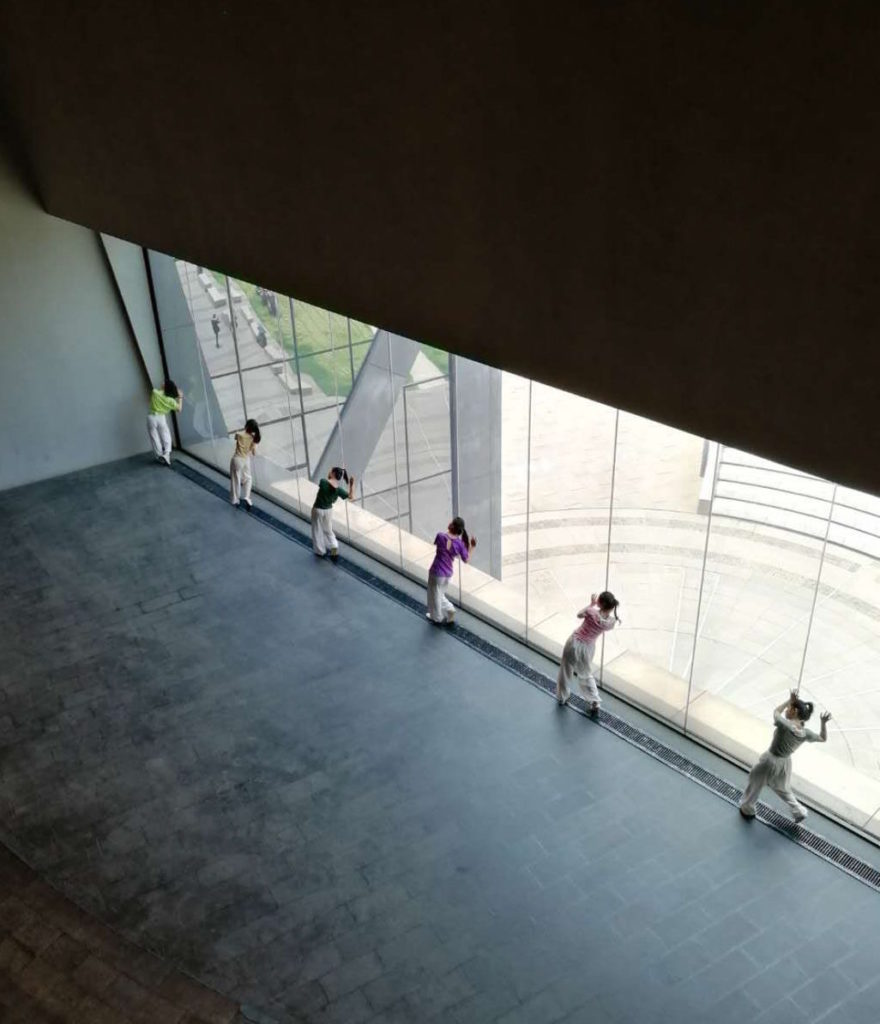

The final event of this forum was a “roundtable,” though we were rushed for time so the table never rounded into a discussion. As the first speaker, I was asked to describe trends that I see in dance today. I chose three that I thought might be transferable: dancing in museums, excavating dance history, and cultural hybrids. One of the following speakers, producer Frank Fu, emphasized the necessity to target new audiences. In response to my talk, he joked that dance in museums is just “making noise or rolling around on the floor.” This ticked me off, so I decided to include more slides of dance in museums in the next leg of my journey (after YY’s forum), which was a lecture on “Judson Dance Theater and Post-Modern Dance.” It so happened that, a few days earlier, the NYC–based Chinese choreographer Yin Mei had premiered a site-specific work to celebrate the new Modern Industrial Museum in Wuhan, Hubei Province. This was a big deal because the museum was designed by world-famous architect Daniel Libeskind. Yin Mei had sent me pictures on WeChat and told me it was live-streamed and viewed by 340,000 people. I hope someone tells Mr. Fu about it!

Tilting Toward the Sky, Yin Mei’s site-specific work at the Modern Industrial Museum, June 2019

We also visited Shanghai Dance School, YY’s old training ground, now part of the Shanghai International Dance Center. They have reason to be proud of their illustrious alumna: YY is the first Chinese ballerina to become an international superstar and has been deemed a national hero. On the wall is a life-size picture of her younger self in a white tutu.

YY with photo of her younger self at Shanghai Dance School

We saw a rehearsal of a garland waltz with lovely, proud 13-year-old girls and boys. But it was the modern dance class taught by Kong Lin Lin that grabbed me. She had 14-year-olds yanking their legs up, throwing themselves off-balance, twisting and turning, ducking under each other—all at the barre even before coming center. At first I was alarmed by the yanking, preferring leg lifts to be somatically supported. But then I was taken by the sheer ingenuity of the steps and the girl-on-girl partnering. The students charged across the floor and threw themselves into very physical pulling and sharing weight, like an aggressive, brisk version of contact improvisation. (Btw, I later saw a workshop given by Beijing CI [Contact Improvisation] for non-dancers of all ages, including three children.)

Modern dance lass of 14-year-olds taught by Kong Lin Lin

Later, Still in Shanghai

After the YY Studio forum was over, I visited a rehearsal of Xie Xin, a rising choreographer who is an artistic associate of Shanghai International Dance Center. She is an extraordinary mover: expansive, range-y, and wild. Her leg swings at the barre activated the rest of her body so that nothing was still, everything was in motion—and that was just her instant warm-up. Her movement swirls like rush-hour traffic, with arcs all over the place. She seems to have gaga, contact improvisation, Sidi Larbi Cherkaoui, and William Forsythe all in her body. Her work is as fluid and calligraphic as Cloud Gate but more forceful, more raw, and occasionally ominous. Her dancers connect with each other in very physical ways. I’m not the only one who finds her work exciting. In the five years she’s had her company, Xiexin Dance Theatre, they’ve performed in festivals in Europe (she appears at the Festival d’Eté in Paris soon) and she’s collaborated with the Ballet Boyz in London. I am hoping her company comes to the U.S. soon.

Xiexin Dance Theatre in rehearsl, Xie Xin at right.

The link between the events at YY’s forum and the later schedule at Shanghai Theatre Academy was Professor Qing-Yi LIU. A notable dance historian, she was the last speaker in YY’s roundtable and is also one of the people who advocated for bringing me to China. She is the founder and editor of the bilingual Journal of Contemporary Research in Dance, which had published one of my essays on Trisha Brown. According to Miranda Yao, who transcribed the forum tapes, Professor LIU “expressed her disappointment with what’s happening here and now, the mainstream dance community’s lack of creativity/originality, not involved or paying attention to the real world, the real life of real people.” Quite critical—but also showing her desire for a great artist to emerge from China’s training. This gave me a hint of why she wanted me to speak about Judson and to give a workshop: to open up ways for the Chinese dancers to be creative.

I did see plenty of creativity in the workshops I gave. In the first one I applied the Trisha Brown “lining up” method, which I had been part of when she/we made Line Up in the 70s. It’s a group process that allows people to relate to each other in quicksilver manner, then to recall and reconstruct short, 10-second segments of improvisation. The 50 or so students were quick and lively and worked well together. But I think something got lost in translation because they tried to choreograph on each other rather than improvise with each other. And that was OK because I could see their impulses and ideas coming through.

Talking with class in Shanghai. My interpreter, in pink, is Margaret Zhang.

I also gave a lecture on Trisha Brown with photos and videos. At the end of it, Professor Liu, again challenging her colleagues and students, posed a question similar to her earlier comment: With all our excellent training in China, why can’t we produce a master artist like Trisha Brown? At which point, I believe I said, There is no formula for producing a great artist. And I noted too that China has produced major dance artists like Lin Hwa-Min, Shen Wei, Yin Mei and Ma Cong—and those are just the ones I know about.

There’s a new crop of dance artists within China. As arranged by the Chinese Dancers’ Association, I saw informal showings by five independent choreographers. They hailed from different backgrounds, and they showed mostly solo excerpts of longer works. (I am putting family names in upper case.) There was ZHAXI Wangjia, who has worked with Beijing LDTX; LEI Yan from TAO Dance Theater and Beijing Modern Dance Company; ZHANG Yixiang, from National Ballet of China; WANG Zhenbin, who was trained in the military dance academy and choreographs for the navy dance company; and PANG Guan Yu, who is with the Oriental Song and Dance Company. Each one combined powerful dance ability with laser focus, and each had an individual style. I also saw videos of the promising young RAO Yuhong (“Hugo”), and of FEI Bo, who choreographs for ballet companies.

We are looking at a video of Zhaxti Wangjia, who is on the floor. Wu Menghang, next to me, was interpreting. LEI Yan is at right. Photo by Jiao Jiao

Beijing Dance Academy

This world-renowned dance center, with three theaters and more than 60 studios, hosted me in several departments. The first thing I did was watch demonstrations—female and male separately— of Chinese classical dance. Formulated in the 1950s as a way to reflect the essence of Chinese aesthetics, Chinese classical dance combines movements from Chinese opera (which contains acrobatics), martial arts, and ballet. It was banned during the Cultural Revolution but resumed during the period of reform and opening up in the 1980s, when it developed in universities. At first the movement looked very Western to me, with balletic lines and lots of attitude turns and Kitri jumps. But my interpreter Sally CAI, who is Canadian-Chinese, pointed out how this form favors spirals and circularity as opposed to the shooting upward-ness of ballet. The women’s hands curve back, and their torsos spiral into flowing shapes. There’s a yin-yang element, for instance the body goes left before it goes right or goes up before going down. Chinese classical dance is spectacular in its rigor and vigor. A few women did 12 split leaps without a breath in between, and then a stag leap before running off. The men do a machine-gun turn (called Sao Tang in Chinese) where they are facing down, three limbs outstretched, and they whip around as their back leg and front arms tap the floor to build momentum.

But where Chinese classical dance became alive artistically was in the repertory class. Though still in very prescribed gender roles, the boys and girls danced together in Yellow River (1988). Heroic masses of men and women surging across the stage in interesting groupings. When their arms were held out to the side, carving the space with elbows upward, it reminded me of the fierceness of Martha Graham’s all-woman masterpiece Chronicle (1936). The whole display was kinetically exciting.

Rehearsal of Yellow River

Another category, folk dance, involves vivid displays and colorful costumes. These are staged versions of various regional dances, with—again—men and women always separate. In Guzi Yang Ge (Seedling Song Drum Dance), the boys start in super limbo position, feet planted firmly, pelvis thrust way forward. Before coming upright, they spiral around to the other side. In the Chaoxian dance, the women wear pale green gowns and dance with slow ritual power. (More varieties of folk dance are taught at the neighboring Minzu University of China, which contains greater ethnic diversity.)

Secondary school boys in a performance of a Tibetan folk dance. Courtesy BDA

BDA’s Department of Creativity sponsored my two compositional workshops, as coordinated by Liu Bing. I gave the lining up workshop here too, with more improvisation beforehand to prepare for it. But it was my second workshop here, with my own approach to group making, that really took off. They did wonderful, impulsive, zany things, fitting themselves into each other’s scenarios—all with a solid sense of form. Well, I should specify that it was the boys who did those things. The girls seemed inhibited. At the end of class, when I asked who wanted to continue choreographing when school was over, almost all the boys raised their hands and almost all the girls kept their hands down. I wasn’t surprised. I had already noticed that the gender divide is similar to the U.S. only more extreme.

Teaching class at BDA. My interpreter, Sally Cai is at my left. Photo by Liu Bing

The Department of Humanities, led by WANG Xin, hosted my PowerPoint lecture, Judson Dance Theater and Post-Modern dance. My talk prompted some good questions from the students and scholars present.

After my Judson lecture, I was surrounded by many scholars including Ou Jianping, Mu Yu, Qing Qing, Wang Xin, Liu Bing, Jessie Zhang, Wu Menghang, and Sally Cai.

One question was, What came after post-modern dance? I think I rattled off some recent developments like dances of cultural identity and urban dance forms like hip hop as concert dance. But I wish I had quoted Yin Mei, who messaged me recently, saying that post-modern dance “opens up possibilities.” So I wish I had said, What comes after is the freedom to experiment.

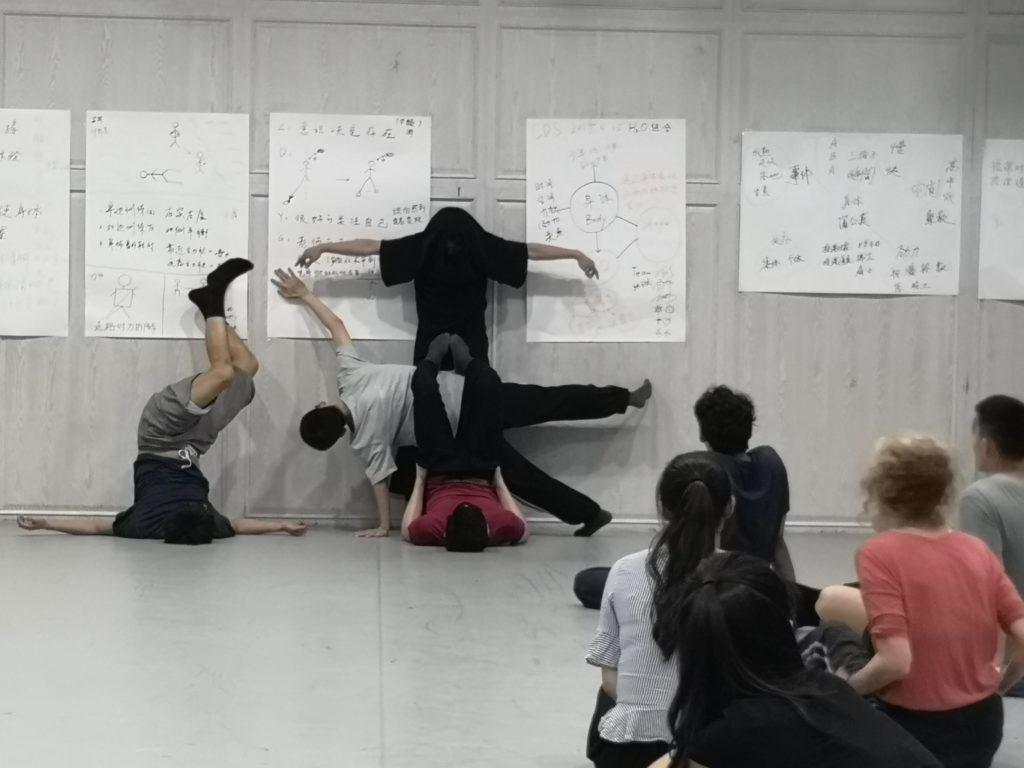

Building a structure one at a time. Photo by Liu Bing

Another belated answer: After one of my lectures, a young woman came up and asked me, “What is the difference between Chinese bodies and American bodies?” Or maybe she said, “Asian bodies and Western bodies.” This is the new way Ph.D. people talk about dance and culture, for example, the “black dancing body,” or the “queer body.” When she asked this question, my response was to point out that there is a great range within Asian bodies, and a great range within Western bodies. I’m afraid I implied that the question was simplistic, reductive. But a couple days later, when Sally CAI and I were on the steps of the vast National Center for Performing Arts, where many families were relaxing or at play, I saw a toddler squatting, folding up his little body as is typical for Asian children. I never see American kids squatting in that exact way—for whatever reason. My thoughts went immediately to the “squatting toilets,” which are more prevalent than seated toilets in China. So now my answer would be, The difference between Chinese and American bodies is in squat-ability.

With class in Creativity Dept of BDA, Sally Cai and me at left. Photo by Liu Bing.

The Humanities Department also sponsored two classes in dance writing. Even though I don’t know the language at all, it’s fun to talk about language. (I had noticed that certain Americanisms are used easily in China: OK, taxi, bye-bye, and Omigod.) About 40 people crammed into the classroom of the first writing workshop. In lieu of a live performance, I showed them Babette Mangolte’s celebrated film of Trisha Brown in her solo Water Motor (1978) and asked them to describe it. Most said words like “free” and “fluid.” But one older gentleman who teaches at BDA called it “madness.” That really gave me pause. I might have joked and said, well all art is a kind of madness. But I do remember that I felt compelled to say the obvious —that the choreographer had created each of those movements herself—because I suddenly felt a wide culture gap as to the understanding of originality—or maybe just a difference in aesthetics.

By the second writing class, they had self-selected down to a more manageable 15 or so. With that size, I was able to send them outside to observe motion in nature and people. And those 15 are serious about dance writing. Some of them, like Mu Yu, have already published books on dance.

From left: Wang Xin, me, Sally Cai

Lingering Thoughts

Swirls of traffic. The bicycles, scooter, motorcycles, and delivery carts are all whisper quiet. They wheel around in arcs rather cross the street in straight lines. But then, everything swirls in China. The carpets in the hotel, and even the small pillow on China Air flights, have swirls. Sally Cai explained to me that the Chinese tend to think in circles and spirals rather than linear patterns. The swirling designs represent clouds and also qi, or chi, the energy of the life force.

Dance dramas. As I mentioned, Neumeier calls The Little Mermaid (and probably all his big ballets) a “dance drama.” That got me thinking about this genre, which is popular in China but not at all in the United States. I cannot think of a single ballet choreographed in our country that falls under the heading dance drama (except possibly some of Ratmansky’s full-length works). Yet in China and in Russia (where they call it dram-balyet—think Spartacus, or Eifman’s Hamlet), it is the major style of ballet.

Dance dramas are based on a story, but they rely more on acting than classics like Giselle or Coppélia. Every scene is highly dramatic and every movement relates to the plot. This form makes sure the audience gets every twist of plot and responds to every intense emotion. It can be heart-wrenching if you’re in the right mood.

But in general, this constant drama doesn’t go over in the States, or at least not in New York. Audiences here want a bit of modulation, of complexity, subtlety. We need the space to come to our own conclusions. The insistence on a detailed narrative seems too literal to us. The work of both Balanchine and Cunningham has attuned us to the pleasures of dance for its own sake. We are energized by a plurality of interpretation; we don’t want to be locked into the roller-coaster of theatricalized emotion.

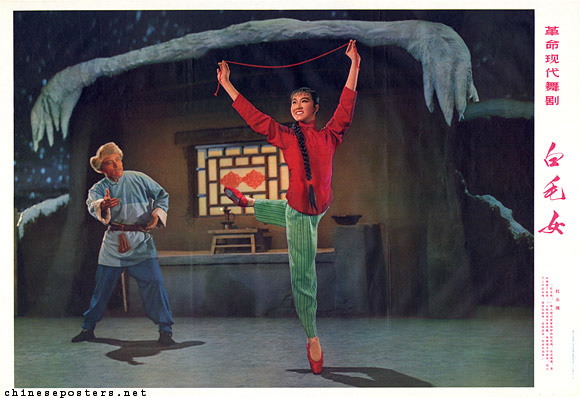

The Chinese preference for dance dramas can be traced back to the two propaganda ballets of Mao’s time. I happened to see one of them, The White-haired Girl (1965), at the magnificent, vast National Center for the Performing Arts, courtesy of Wang Xin in the Humanities Department. It was performed by the Shanghai Ballet, with the heavenly Qi Bingxue as the peasant girl before her hair turns white. Like the more famous Red Detachment of Women, this was created (by committee, it seems) to glorify the struggle of the workers. What I loved is that it shows women in trousers the whole ballet through. No filmy sylphs or evil seductresses in these Communist ballets! The sweetness of Qi Bingxue’s upper body made the ballet appealing to me, and we saw her exquisite legs and feet through those silky trousers.

A 1973 poster for The White-haired Girl

This ballet was made in 1965 as a dance version of the classic 1945 opera. So there’s a leftover opera feeling, with a bad recording of typically shrill old-fashioned arias at the beginning of each solo—as though the choreographic committee didn’t trust that dance itself could fully express the narrative situation.

But I was impressed that women were the heroes in this ballet (as well as in The Red Detachment of Women.) Apparently Mao had proclaimed, “Women hold up half the sky.” The fact that women had been even more downtrodden than men in feudal times made for a greater heroic leap to imagine women as leading the revolution. Let me add that in all other ways this ballet conforms to the typical dance drama aesthetic: very obvious characters, emphatic acting in every scene, and a super clear story of heartbreak and heroism. The soldiers are all motivated, their girlfriends are happy, and the landlords are all tyrants. The choreography mainly pushes the message along—with detours for divertissements like the traditional ribbon dance—but with very little inventiveness.

However, with a bit of irony, a bit of noir, a bit of imagination, this form can be scintillating. I was thrilled to witness the rehearsal of Shanghai Dance Theater in a new, quite brilliant dance drama titled The Eternal Wave. It is based on the 1958 spy novel of the same name. (Shanghai Dance Theater is very different from the Shanghai Ballet, though both are housed in the Shanghai International Dance Center and both have more than 100 dancers.) The dancing was technically superb, the acting was intense, and the choreography was well crafted. I wasn’t surprised to learn that this ballet, choreographed by two women, Han Zhen and Zhou Liya, won the Ministry of Culture’s highest prize (Wen Hua Prize) for this last season. The choreography was ingenious in its formations and inventive in its detail—not at all predictable like the propaganda ballets. It was full of mysterious encounters, highly stylized tableau, brilliant use of trench coats, and a thrashing solo for the male protagonist that was both poignant and powerful. Wish I could’ve stayed an extra week to see it performed onstage.

A scene from The Eternal Wave in performance.

Gender stereotypes. In all the training sessions, the classes were separated by gender. In Chinese classical dance, the women’s faces were adorned with unfailing smiles. Whether the smiles were cheerful, sad, or strained, they signaled a desire to please. A willingness to be accommodating. A sense of confinement. The men showed their strength by striding confidently or lunging as though wielding a weapon. In both cases, the phrase “trapped by gender” entered my mind. Of course ballet is also gender-bound, and so is flamenco and many other dance forms. This is not unique to Chinese classical dance.

It seems to me that the first step to opening up creativity is to bust out of gender straitjackets. And the Chinese dance scene already has an example: Jin Xing, The famous Chinese dance artist who transitioned from male to female. She had her own dance company and then her own TV show. (Read about her in “Nine Who Dared” in Dance Magazine in 2012: Xie Xin, the choreographer I mentioned before, danced in Jin Xing’s company, and I found Xie Xin own androgynous look appealing. Also the choreographers I saw in the China Dancers’ Association seemed far less gender-bound than the young people in classes. And visiting companies, like Akram Khan and Batsheva Dance Company from Israel, have brought their more adventurous outlook to Shanghai International Dance Center. With all these new influences, here’s hoping the dance training will evolve to eventually loosen gender expectations.

I want to thank the many people who made this visit such an enriching experience, starting with Yuan Yuan TAN, whose invitation made this trip possible. Lan-Lan WANG, Professor Qing-Yi LIU and WANG Xin were the other active organizers. My main interpreters—Brenda LIU in Shanghai and Sally CAI in Beijing— went beyond the call of duty, guiding me in more ways than just language. Many others who gave generously of their time and expertise. In Shanghai they included YI Ding, Olivia LYU, Angel, Claire, LIN Nan, Shelley LIM, ZHANG Ling, Mother and Father TAN, Margaret ZHANG, Miranda YAO, and XIE Xin and her husband. In Beijing: XU Rui, vice dean of BDA; Jessie ZHANG, Cecilia ZHAO, LIU Bing, ZENG Jie and SHEN Peng, ZHANG Ping of China Dance Magazine, WU Menghang, Cissy YANG, and JIAO Jiao of China Dancers’ Association. Also, it was an honor to meet Mme. ZHAO Ruheng (“Sonia”), artistic director of dance at the National Performing Arts Center and vice president for Beijing International Ballet and Choreography Competition, and scholars OU Jianping, MU Yu, and QING Qing.

Last workshop in Creativity dept at BDA. Photo by Liu Bing

Featured 7