Dance is all about motion, so when I say “imprinted memories,” I don’t mean a single still image. I mean how things flowed, or an inchoate sense that something different is happening. I like it when the dancing doesn’t fall into the easy thing, the cliché, but gives off a whiff of humanity in a new way. This list is limited by what I happened to see this year. These are the (admittedly New York–centric) performances that have left me with that kind of imprint.

NEW CHOREOGRAPHY

One. One & One, choreographed by Noa Wertheim for her Israeli group, Vertigo Dance Company, at Baryshnikov Art Center.

One. One & One, Korina Fraiman, aloft, and Etai Peri, ph Stephanie Berger

Agitated, bold, expansive. The dancers spread dirt on the floor as though planting. Held-in emotions get released into the air, into nature. In one grappling duet, the man and woman are slightly dangerous to each other. Then with a sudden buoyancy, the woman is flying/floating . . . a weathered kind of ecstasy. This trailer gives you some idea of why I was so affected by this performance.

Ink, by Camille A. Brown, at the Joyce.

Maleek and Yusha-Marie Sorano in Ink ph Christopher Duggan

Movement vocabularies drawing from a range of African diasporic forms. Solos of despair, courage, and joy. Duets of different relationships, different vocabularies. One kinetically exciting duet, based on the jitterbug, is made dense with intricate details in the hands and feet while fueled by the basic rhythm. The seven take-charge dancers, including Brown and long-term associate Juel D. Lane, were thrilling to watch.

End Plays, by Lisa Nelson with HIJACK (Kristin Van Loon and Arwen Wilder), at Roulette.

Arwen Wilder and Kristin Van Loon in End Plays, ph Ryan Fontaine

The attention to objects and to each other was quietly intense. When you hear the words “End, reverse, repeat” you think you know what’s going on. But these commands (Nelson calls the process real-time editing) were followed or not followed seemingly at random, and that’s part of its playfulness. The space appeared empty; gradually objects appeared seemingly out of nowhere. The communication between the three performers and the objects seemed to depend on a hidden, subterranean language.

The Road Awaits Us (2017), by Annie-B Parson, co-directed by Paul Lazar, with text excerpts from Ionesco and Chekhov, at NYU Skirball.

Bravo for using older dancers with wit and whimsy! Bebe Miller, Douglas Dunn, Meg Harper, Keith Sabado, Betsy Gregory, and Black-Eyed Susan brought their own weathered warmth to this delightfully absurdist journey. Seeing Douglas Dunn as a fire chief is indelible in my mind’s eye.

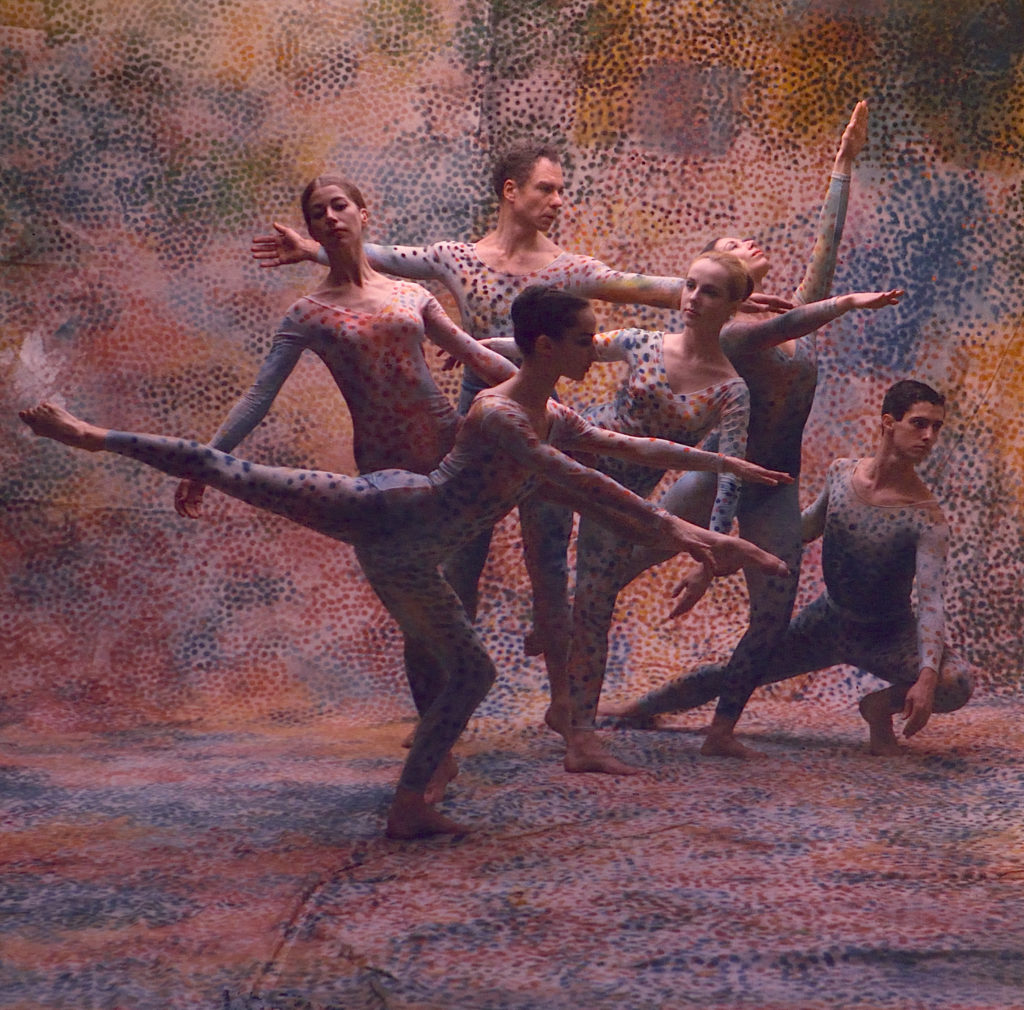

To Create a World, by Andrea Miller in collaboration with the Gallim dancers, at the Joyce.

To Create a World ph Yi-CHun Wu

A dancer hatches out of a huge cloth that could be a shroud, or just as easily, amniotic fluid. Lots of fetal position, animal closeness, and crawling into each other’s negative spaces. Images of grieving and nurturing, for example, dragging away a victim, co-exist with the brutality of nature. The lighting evokes fire and ice. Extinction. The end is the beginning is the end.

In Absentia (2018), U.S. premiere, by Kim Brandstrup, part of Natalia Osipova’s “Pure Dance with David Hallberg,” at NY City Center.

David Hallberg, In Absentia, ph Johan Persson

This solo for Hallberg finds him sitting on a chair watching himself on a television monitor, clicking the remote morosely. It’s a rehearsal. But with the shadows and silence, a noir feeling hangs in the air, and the dancer seems sucked into a kind of no-exit situation. Hallberg brought it off with chilling sincerity and existential gloom.

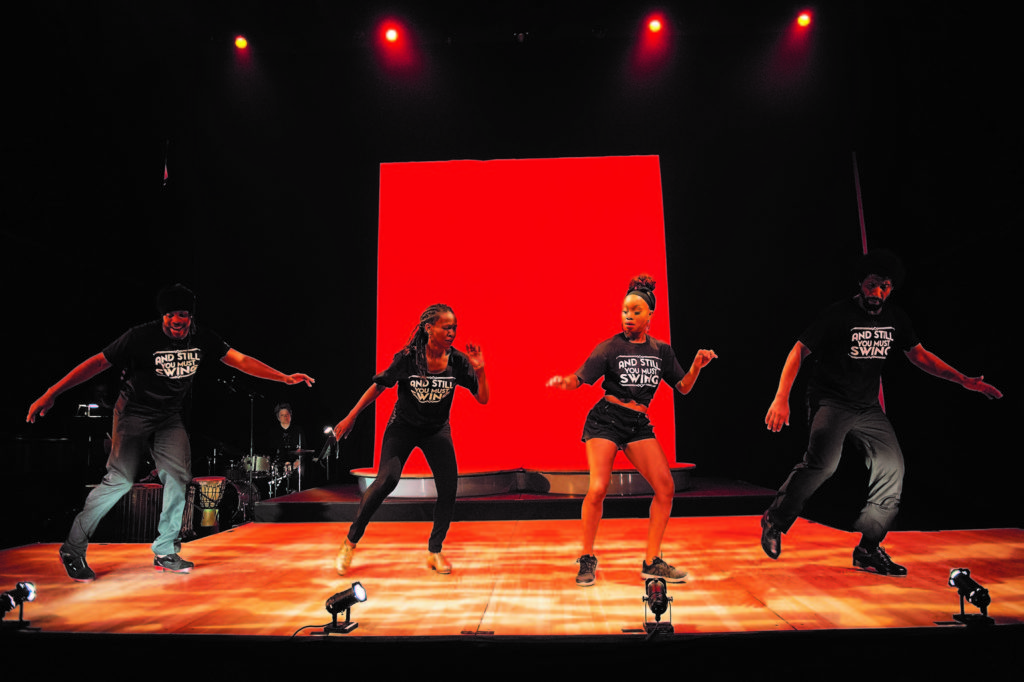

And Still You Must Swing, conceived by Dormeshia, choreography and “improvography” by Jason Samuels Smith, Derick K. Grant, and Dormeshia, at the Joyce.

And Still You Must Swing, ph Christopher Duggan

These powerhouse tap dancers exercised their exhilarating virtuosity, camaraderie, and sense of humor. Guest artist Camille A. Brown brilliantly folded Africanist movements into the shapes and rhythms of the tappers.

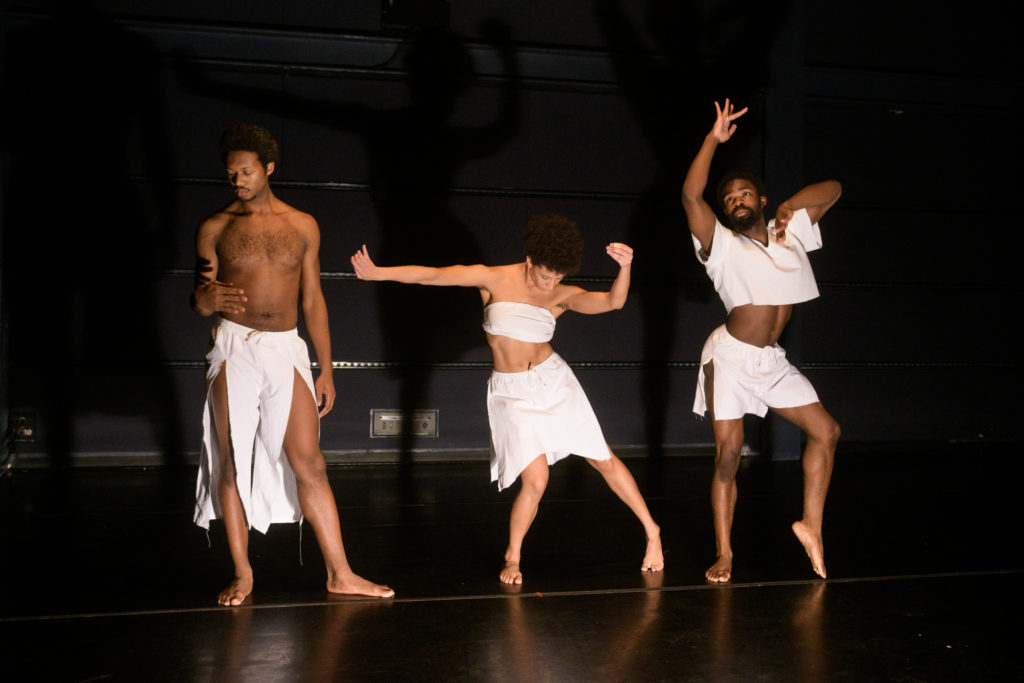

Colored (2017), NYC premiere, by Kyle Marshall, part of Next Wave Festival at BAM Fischer, originally commissioned by Dance on the Lawn Montclair Dance Festival.

Colored with Kyle Marshall, Myssi Robinson, Oluwadamilare Ayorinde, ph Ian-Douglas

This trio—Marshall, Myssi Robinson, and Oluwadamilare “Dare” Ayorinde—starts with a postmodern pattern of gestures and evolves into something more personal and symbolic—symbolic of black culture, of Christianity. The meditative, interior sense of Marshall’s own performing resonates in the space. Memory, culture, and intimacy all collide in a very affecting way.

Dare to Wreck (2017) choreographed and performed by Madeleine Månsson and Peder Nilsson of Skånes Dansteater, part of Fall for Dance, NY City Center.

A harrowing relationship between a woman in a wheelchair and an able-bodied man. Attachment and resistance, with equal strength on both sides. Keen suspense: How will they connect or not connect? How will they survive being alone? How will they survive each other’s harshness?

Bzzzz, by Caleb Teicher with beatboxer Chris Celiz, commissioned by Fall for Dance at NY City Center.

Bzzzz, with Caleb Teicher, center, ph Stephanie Berger

This was crazy good fun with solo and group tap dance. The secret to their rhythmic propulsion: short moments of silence cropping up when you least expect them.

William Forsythe: A Quiet Evening of Dance, a Sadler’s Wells production co-commissioned by The Shed (which I wrote about here.)

A Quiet Evening of Dance, ph Mohamed Sadek

In the first half of the program—the quiet half—the dancers worked together in twos and threes. They were problem-solving, twisting or hurling themselves into some structure we didn’t know, or tying the body into and out of knots. The second half was business as usual: a performance for the audience, with music (by Rameau).

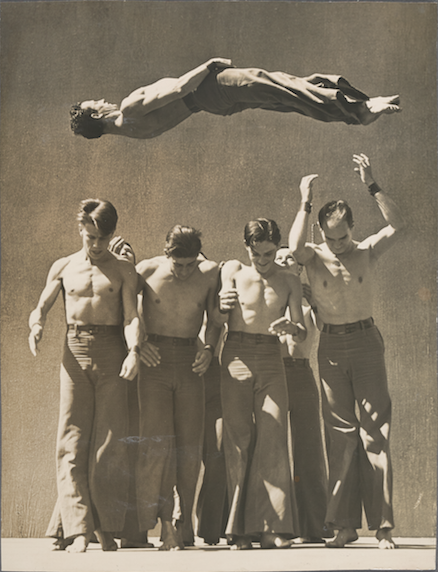

VITAL REVIVALS

Live! The Realest MC (2011), by Kyle Abraham at NYU Skirball.

AIM_Live! The Realest MC, ph Julien Benhamou

Taking the cadence and shapes of the lopsided ghetto stride and extending them into arias of yearning, power, and disintegration. Approaching the mic but not speaking into it. Finally a fragment of narrative: “They held me down and spit on me.” These are ghostly shards of an experience of gender and racial bullying. Pain and poetry. Wistfulness.

The Stephen Petronio Company in Merce Cunningham’s Tread (1970) at NYU Skirball, with the original set of ten standing electric fans by Bruce Nauman.

Tread with Petronio dancers, ph Ian Douglas

One of the few really playful Cunningham works. One person wedges herself under the crook of the knee of a sitting man. Bodies alternate between having agency and being a still object, sometimes held horizontally. A fun game of the body as puzzle.

Deuce Coupe (1973) by Twyla Tharp, revived by American Ballet Theatre.

Deuce Coupe at ABT, ph Gene Schiavone

Although it’s not the same as the first time out, this was an exciting revival.

Come Sunday (1960s) by Geoffrey Holder, at Fall for Dance at NY City Center.

This soulful solo, made for the exquisite Carmen de Lavallade, was transferred to a current exquisite dancer, Alicia Graf Mack. This clip, from the section danced to “He’s Got the Whole World in His Hands,” from Gia Kourlas’s #SpeakinginDance series shows Graf Mack in rehearsal.

Parts of Some Sextets (1965), choreography by Yvonne Rainer, reconstruction by Rainer and Emily Coates, within Performa•19.

David Thomson, Emily Coates, Jon Kinzel in Parts of Some Sextets, ph Paula Court

Eleven people share the stage with 10 mattresses, all 21 entities engaged in a variety of tasks. The text, the “Diary of William Bentley” from 1783 to 1819, was a bit unpleasant (“Most women have no character”) but the bare honesty of his reaction to various animals and deformed humans was one track of reality running parallel to the wholesome, diverse cast in this precisely timed slice of life.

Rosas danst Rosas (1983), danced by a younger generation of Anne Teresa De Keersmaeker/Rosas, at New York Live Arts.

Rosas danst Rosas at New York Live Arts

A limited palette of gestures performed with sharpness and urgency. A sudden inhale sucks the body up as though held by the throat. Restless rest, thrusted twisting, agitated stillness. The exhaustion of merciless repetition rips away at precision.

City of Rain, a 2010 piece by Camille Brown, with music by Jonathan Melville Pratt, remade for Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater this season.

City of Rain with Ailey dancers, ph Paul Kolnik

Mourning a friend who died, dancers with hands on heart. Allowing the energy to emerge from feeling and caring, spurts of anger lifting the heads and the tempo. Spinning poetry from grief.

POIGNANT STORYTELLING

The musical Choir Boy, written by Tarell Alvin McCraney and choreographed by Camille A. Brown.

Choir Boy, Jeremy Pope sitting in front row, foreground

The extraordinary Jeremy Pope, as a young gay man with a heavenly voice and a hellish life, is trying to survive in a black boys’ prep school. The character’s courage and vulnerability tore my heart. The step dance choreography by Brown allowed the characters to burst forth with their rage, hurt, and determination. (By now you can see that it’s been a banner year for Camille A. Brown.)

Swan Lake/Loch na hEala, written, directed, and choreographed by Michael Keegan-Dolan for the Irish theater group Teac Damsa, at BAM Harvey Theater as part of the Next Wave Festival.

Swan Lake/Loch na hEala, Alexander Leonhartsberger, center, ph Stephanie Berger

A young man named Jimmy, played by Alexander Leonhartsberger, is caught in a downward spiral of loss and loneliness. He falls in love with a girl who, because she was sexually abused by a priest, is silenced by being turned into a swan. Sadness upon sadness. This dark fairytale is spiked with humor. For only a few minutes, Leonhartsberger dances— and you’re left longing for more.

STANDOUT PERFORMERS

Best Debut in a Classic Role

Calvin Royal III in Balanchine’s Apollo with American Ballet Theatre.

Calvin Royal III in Apollo, ph Rosalie O’Connor

A lift in his chest gave him a natural godlike quality. He invested in details of the choreography like the wrists flipping and resting his head on the palm of one of his muses, with his ennobling attention. An Apollo for the ages. Click here to watch him rehearse the role.

Best First Solo

Carrying Floor (2018), choreographed and performed by Abel Rojo of Malpaso Dance Company, with music by Satie, at the Joyce. Rojo placed squares of tiling down, marking where he’s going and where he’s coming from. His body twisted and curved, reacting to each decision, sometimes with peacefulness and other times with challenge. A simple idea, yet fully engrossing.

Motown Superstar

Ephraim Sykes as David Ruffin in Ain’t Too Proud: The Life and Times of the Temptations. The hyper-energized Sykes dove into sensational extremes; he’d bound straight in the air and slam back down into a sliding split. Sheer, adrenaline-fueled, shakin’-down-the mic wildness.

Ephraim Sykes as David Ruffin in Ain’t Too Proud: The Life and Times of the Temptations. The hyper-energized Sykes dove into sensational extremes; he’d bound straight in the air and slam back down into a sliding split. Sheer, adrenaline-fueled, shakin’-down-the mic wildness.

Ballet Dancers Throw Themselves into Merce

Adrian Danchig-Waring and Lydia Wellington in Merce Cunningham’s Summerspace (1958) at NYCB. This classic modern dance piece is spare, sequenced by chance procedure, and basically unmusical—though with sharp timings. These two commanded the stage with an alertness that made you feel anything could happen—an illusion that’s even difficult for long-term Merce dancers to carry off.

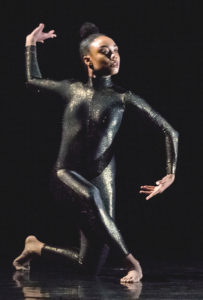

Urban Glamour

Urban Glamour

Marcella Lewis in Show Pony (2018) by Kyle Abraham, at the Joyce. A glorious example of Abraham’s amalgam of strutting, contemporary dance, and hip-hop tropes. Her quicksilver transitions from one mode to another were electrifying.

Breaking New Ground

Chalvar Monteiro of Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater. In April he bounded onto the stage in Night of 100 Solos of the Cunningham centennial at BAM with striking vigor. During Ailey’s winter season at New York City Center he lilted and swiveled through the mercurial opening solo of Aszure Barton’s Busk. He’s grown into a powerhouse since three years ago when Gia Kourlas wrote this “On the Rise.”

Anguish in the Bones

Anguish in the Bones

In Gallim’s drastic To Create a World, Gary Reagan is the most extreme form of drastic. His limbs emerge from what looks like a pile of bones to stretch and contort in bizarre ways. He could be being born or dying—or just barely surviving. Evoking images of the holocaust, he dances with a desperate, last-day-on-earth intensity. Not “beautiful,” but unforgettable.

Master Improviser

David Zambrano in Una Protesta at Movement Research at Judson Church, with live singing by Yva las Vegass. Solidly rooted yet impulsive, he took small steps like a geisha, gliding and skittering though space. Sudden whole-body pounces like a frog, vibratory extremities like a leaf in the wind, light laughter that hints at a wellspring of joy. Well-matched with the edginess of las Vegass’ singing, though they hadn’t met before.

BEST NON-BINARY CONCERT

The entire ‘Explode! Midwest Queer Dance Festival” at Links Hall in Chicago, curated by dance scholar Clare Croft.

LaWhore Vagistan, ph Al Evangelista

Crossing boundaries of gender and genre, this shared concert was hosted by the outrageous LaWhore Vagistan. It included work by Murad Mommy, Lee na-Moo, J-Sun Howard, and Jennifer Monson. For a full account, click here.

MERCE WAS EVERYWHERE

Night of 100 Solos, Chalvar Monteiro, center in blue, ph Stephanie Berger.

During this centennial year, evidence of Merce Cunningham cropped up in performances, live streams, books, films and on Twitter. High points included NYCB in Summerspace (1958), the program at the Joyce with The Washington Ballet in Duets (1980), Compagnie CNCD-Angers in Suite for Five (1956), and Ballet West in Summerspace. “Conversations with Merce,” curated by Rashaun Mitchell, gave three very different artists— Mina Nishimura, Netta Yerushalmy, and Moriah Evans—a chance to speak to Merce in their heads and on the Skirball stage. Stephen Petronio Company reconstructed Tread (mentioned above). For the Night of 100 Solos at BAM, visual artist Pat Steir provided a spectacular water-falling backdrop for 30 dancers who had never performed Cunningham work. Topping the centennial off are Merce Cunningham Redux, the newly augmented book of James Klosty’s fabulous photos from the 1970s; the re-issue of Cunningham’s notes titled Changes; and the 3D movie Cunningham. All of which are reminders that the master rebel took us from modern to postmodern, from the 20th century to the 21st, with uncompromising experimentation.

HURRAH FOR WOMEN LEADERS!

Wendy Whelan, who has, in her dancing and her collaborations, done so much to bridge the gap between ballet and contemporary dance, was chosen to co-direct New York City Ballet. We’re eager to see how she helps shape the NYCB repertoire. Alicia Graf Mack is now in her second year of leading the dance division of The Juilliard School, which provides equally rigorous training in modern dance and ballet. Call me biased, because I know them both (and am teaching part-time at Juilliard) but having these two glorious dance artists in top positions is good news for the dance world.

On the journalistic front, Gia Kourlas was appointed the new chief dance critic of The New York Times. Happily, she is covering dance more from the inside than any chief critic before her—following her curiosity to interview a wide range of dance artists and give them a voice. She is illuminating dance wherever she finds it, not simply going along with the ballet-is-best hierarchy we’ve seen before. Onward!

YEAR AFTER YEAR

Four dancers have each been performing one iconic role in Balanchine’s Nutcracker at New York City Ballet for so long that they are now associated with those roles. They add sensuality, shimmer, virtuosity, and intrigue to a beloved NYC tradition: Georgina Pazcoguin as Coffee since 2006, Megan Fairchild as Sugarplum since 2003, Daniel Ulbricht as Candy Cane since 2000, and Robert La Fosse as Drosselmeier since 1993.

Georgina Pazcoguin, ph Paul Kolnik

Megan Fairchild, ph Erin Baiano

Daniel Ulbricht, ph Paul Kolnik

Robert La Fosse, ph Paul Kolnik

The annual Table of Silence Project 9/11, conceived and choreographed by Jacqulyn Buglisi is performed at 8:20 am, the moment the first airplane struck the World Trade Center. The somber beauty of this ritual, with more than 150 dancers including illustrious guest artists like Terese Capucilli and Virginie Mécène, allows us to feel the enormity of what happened and how we linger in the shadow of 9/11. This annual ritual, so elegantly choreographed, gives dignity to our shock and grief.

Table of Silence, ph W. Perron

A shout-out to the many freelance dancers who serve as the backbone of Broadway musicals. My favorite example is Bahiyah Hibah, who’s graced many Broadway ensembles, the latest being Moulin Rouge, with her elegance and musicality. I’ve also seen her in Evita, Memphis, On the Twentieth Century, Rock of Ages, and After Midnight. She lends these productions a certain glamour but often disappears into the action unless you look for her. This summer she was awarded the annual Legacy Robe, that is passed down to a hard-working trouper.

Bahiyah Hibah in Legacy Robe

Featured Leave a comment

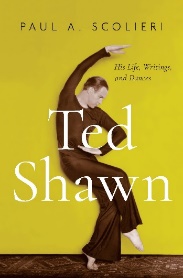

Ted Shawn: His Life, Writings, and Dances

Ted Shawn: His Life, Writings, and Dances

Jerome Robbins, by Himself

Jerome Robbins, by Himself A Body in the O: Performances and Stories

A Body in the O: Performances and Stories Ray Bolger: More Than a Scarecrow

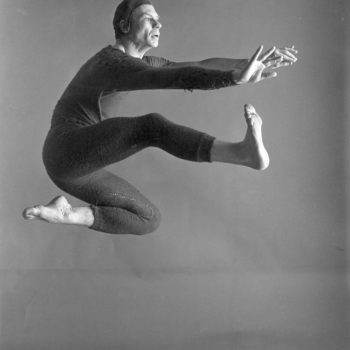

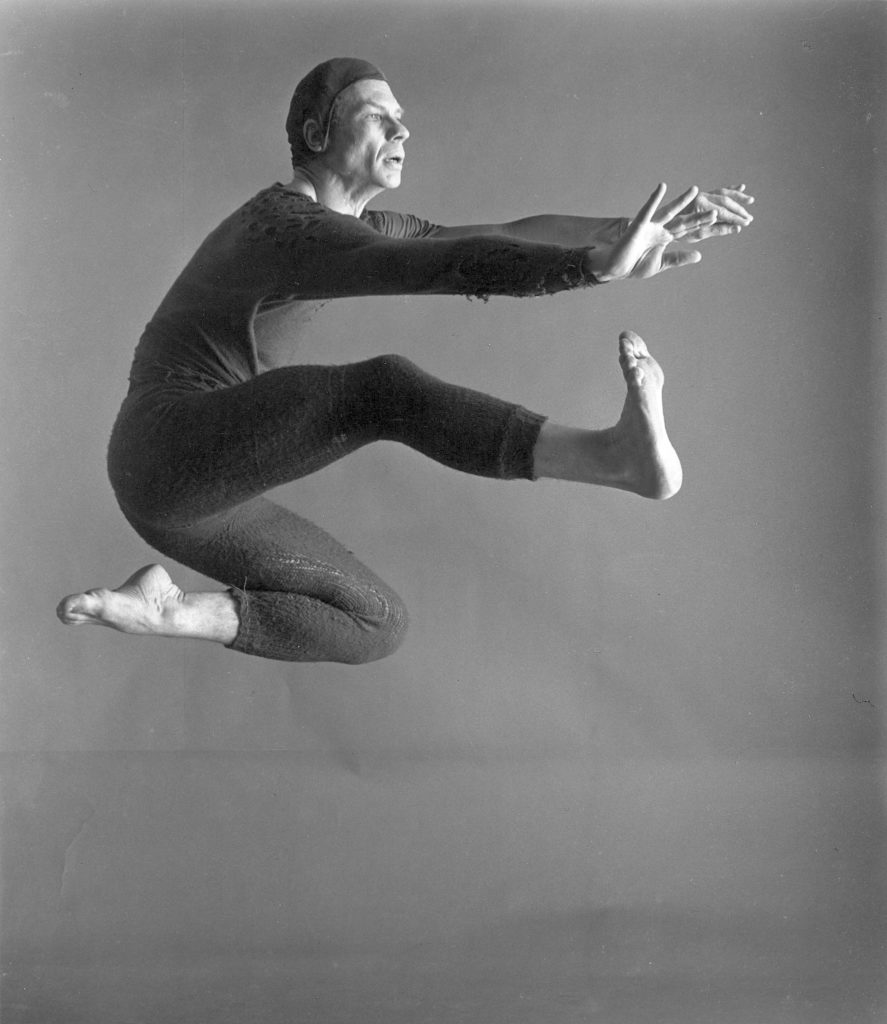

Ray Bolger: More Than a Scarecrow Dancing with Merce Cunningham

Dancing with Merce Cunningham And while we’re on the subject of Merce…

And while we’re on the subject of Merce… How to Land: Finding Ground in an Unstable World

How to Land: Finding Ground in an Unstable World Revolutionary Bodies: Chinese Dance and the Socialist Legacy

Revolutionary Bodies: Chinese Dance and the Socialist Legacy Broadway, Balanchine & Beyond: A Memoir

Broadway, Balanchine & Beyond: A Memoir Keep It Moving: Lessons for the Rest of Your Life

Keep It Moving: Lessons for the Rest of Your Life Glory: A Life Among Legends

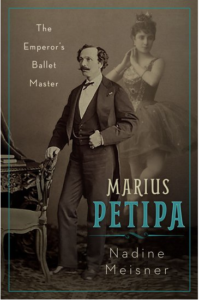

Glory: A Life Among Legends Marius Petipa, The Emperor’s Ballet Master

Marius Petipa, The Emperor’s Ballet Master