Courtesy Wesleyan University Press

The brilliant dance critic and historian Sally Banes, who pioneered a new way to write about dance as a social phenomenon, died on June 14, 2020, in Philadelphia. Her husband, Noel Carroll, said the cause was ovarian cancer.

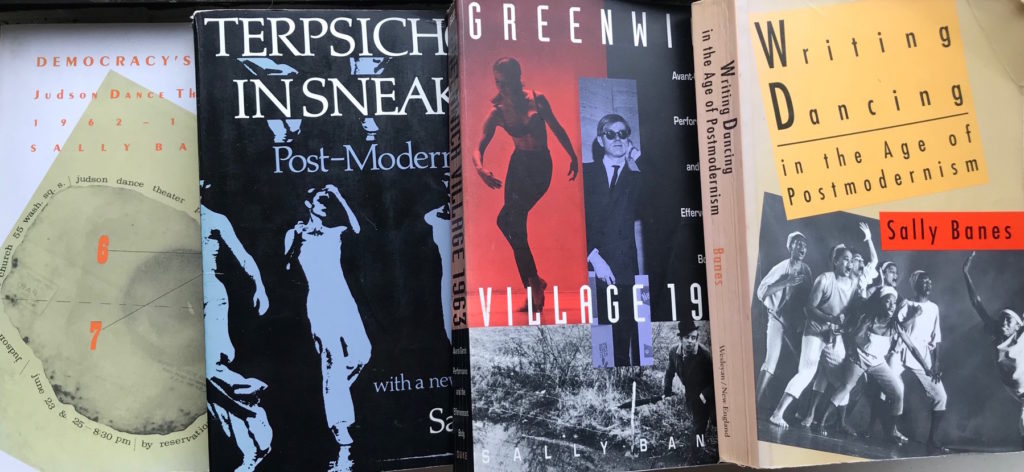

Banes visited New York in October 1973 with a standard assignment: to write a book on modern dance for Chicago Review Press. Because of her curiosity about choreography, instinct for the experimental, and scintillating prose, she produced, in 1980, one of the most essential dance books of the twentieth century: Terpsichore in Sneakers: Post-modern Dance.

Shifting her attention from SoHo to the Bronx, Banes was the first dance critic to write about the exciting new urban form known as break dancing. Her article “To the Beat Y’All: Breaking is Hard to Do,” in the Village Voice in April 1981, introduced break dancing to readers before there was even a name for hip-hop culture. Fascinated by what she saw, she returned to this genre again and again.

Although these were her two favorite subjects—the (largely white) avant-garde and (largely black) urban dance—she investigated many other passions over time. In seven additional books on dance and a myriad of essays, she explored subjects ranging from the influence of black dance on Balanchine, to the drunk dances of Fred Astaire, to the Russianness of Firebird, to the knotty problem of appropriation. She held a string of college teaching-and-research positions and earned several lifetime achievement awards. She’s been a leader in the burgeoning field of dance studies, challenging her peers to rise to her level of intellectual rigor paired with vibrant prose.

Banes grew up in Silver Spring, MD, taking ballet lessons in nearby Washington, DC. She attended the University of Chicago, where she participated as a script writer and performer in a group called The Collective. She graduated in 1972 with an interdisciplinary degree in criticism, art, and theater. The following year she started writing criticism for the Chicago Reader and became its dance editor while also writing book reviews for the Chicago Daily News. During the same period, she founded the Community Discount Players, which she called “a motley collection of performers, dancers, and wizards.” She created performances that were part dance, part theater, part every-day happening. In 1974 she participated in the creation of Meredith Monk’s Chacon at an Oberlin residency. That same year, she was a co-founder of MoMing Dance and Arts Center, which was a collective as well as a presenter. She performed there with New York choreographer Kenneth King. According to dancer Carter Frank, “Without her guiding light and her enthusiasm, MoMing would not have made such a mark in Chicago. It was where I got to see people whom I had only read about in the Village Voice and it was like getting a drink of cool water in the desert.” It was at MoMing, after a 1975 performance of the improvisational group Grand Union, that she met her future husband, philosopher and critic Noel Carroll.

Collaboration with Ellen Mazer: “A Day in the Life of the Mind, Part 2,” 1975, The University of Chicago, ph Frank Gruber

Banes and Carroll moved to New York in 1976. She took class at the schools of Graham and Cunningham and the downtown Construction Company, and workshops with Simone Forti. She performed in Forti’s large improvisatory group work, Planet (1976) at P.S. 1 in Queens. (Forti was a lion, Pooh Kaye a bear, and Banes an elephant.)

The “Concepts in Performance” page of the SoHo Weekly News was the first to review the new boundary-crossing performances that defied the categories of dance, theater, poetry, or visual art—before the term performance art was coined. Banes wrote for this page from 1976 to 1980, becoming editor the last two years. She was given her own column called “Performance” in the Village Voice from 1980 to ’85, where she reviewed major artists like Meredith Monk, Robert Wilson, and Laurie Anderson. She also reviewed singular performers before they became big names like Whoopi Goldberg (“careening from bathos to pathos”), Steve Buscemi (“like a human rubber band”), Eric Bogosian (“a raw, cognitive screech”), and Karen Finley (“this messy scabrous conduct exhilarated us”). These reviews are reprinted in Subversive Expectations: Performance Art and Paratheater in New York 1976–1985 (1998).

Banes adopted, in her own words, a stance of “knowing innocence” and a “sense of wonder.” She wasn’t wowed by mere virtuosity but was attracted to the questions posed by the mind/body of an enquiring artist. Whether she was writing in Dance Magazine or Dance Chronicle, she situated every artist in a social context. Her prose was informal, witty, and spontaneous, and she could paint a picture in words that was as startling as the performers themselves.

Sally wore her socialist feminism on her sleeve; she never tried to be “objective.” Reading her words, you got a strong sense of her presence at the performance. She was in line with the Duchampian idea that each work of art was not complete until the audience experienced it.

For Judson choreographers like David Gordon, Trisha Brown, and Steve Paxton who appeared in Terpsichore, and for break dancers like the Rock Steady crew, she was a staunch advocate. She took her advocacy further when, in 1978, she decided that Yvonne Rainer’s solo Trio A from 1966 had to be preserved. Although most critics were indifferent or worse—Clive Barnes labeled it a “total disaster” in The New York Times—Sally regarded this not-quite-five-minute sequence an exemplar of post-modern dance. Rainer agreed to re-perform it for the camera, even though by then she was a filmmaker who hadn’t danced in years. Originally a trio section of The Mind Is a Muscle, Trio A embodied all of Rainer’s studied defiance: odd, unmusical phrasing; looking away from the audience; eschewing repetitions that would make for a legible structure. Trio A has become a symbol of, or gateway to, postmodern dance—which probably wouldn’t have happened if Sally had not filmed it.

In 1980 Banes earned a PhD from the Department of Graduate Drama at NYU, later named the Department of Performance Studies. In 1983, Banes turned her dissertation on Judson Dance Theater into a book, Democracy’s Body: Judson Dance Theater 1962–1964, reprinted by Duke University Press in 1993. She framed the unruly Judson collective as democracy itself. This book has been the touchstone—or target—for younger scholars seeking to make their mark in contemporary dance.

In 1983, photo: WP

Making the shift from journalism to academia, she edited the scholarly Dance Research Journal from 1982 to 1988. There was a period of cross-fade when she was writing less journalism and more academic essays. Whether journalistic or academic, Banes’s writing possessed both intellectual heft and sensuous description.

Still invested in the sixties, she took the densest year of Judson, 1963, and expanded her research into the political, social and artistic activity during that time. Greenwich Village 1963: Avant-Garde Performance and the Effervescent Body, published in 1993, describes the intersecting constellations of Andy Warhol, jazz musicians, underground film, avant-garde playwrights, beat poets, and Bread and Puppet Theater.

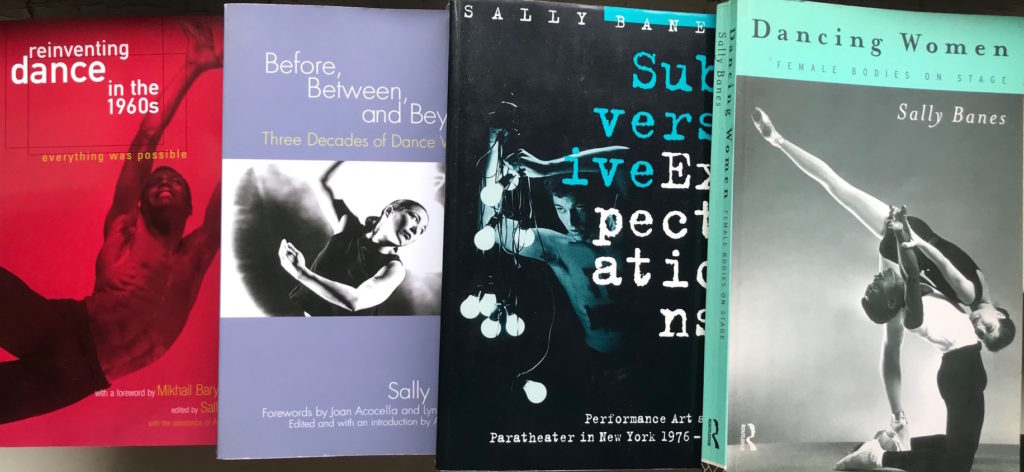

In Writing Dancing in the Age of Post-Modernism, her 1994 collection, Banes conflates “the avant-garde, the popular, the commercial, and the vernacular.” Her interests range from post-Judson choreographers Bill T. Jones and Molissa Fenley, to emerging Latino choreographers, to, of course, break dancing. In Dancing Women: Female Bodies on Stage (1998), she brings a feminist angle to women’s roles in the canon of dance from Romantic ballet to recent modern dance.

Sally was a radiant person, bursting with life. Her enthusiasms were contagious and her knowledge was vast. She championed artists from Yvonne Rainer to Urban Bush Women, Merce Cunningham to Tim Miller. She delved into historical pockets that aren’t in “the canon,” like Ballet Suédois of the 1920s and the leftist Workers Dance League in the 1930s. On the advice of dance historian Selma Jeanne Cohen, she started studying Russian and quickly developed an interest in Soviet experimental choreographers of the 1920s.

Banes’ college teaching career began in 1980 at Florida State University. From 1981 to 86 she taught at SUNY Purchase, followed by two years at Wesleyan University, then three at Cornell. In 1991 she became associate professor of dance and theater at University of Wisconsin Madison, and chair of the dance program from 1992 to ’96, when she was named the Marian Hannah Winter Professor of Theater History and Dance Studies.

Lori Brungard, a faculty member in Hunter College’s dance department, studied with Banes at SUNY Purchase in the mid-1980s. “With her big coke-bottle glasses and her lisp and her energy in what she was talking about,” Brungard recalled, “I wouldn’t expect to be engaged by this person but I was. She was like wooo! but still focused. She had this phosphorescence, a glow. Light emanated from her and she induced a light in me.” Brungard felt enriched by what Banes was teaching: “One bridge she made was the connection to the African diaspora. She was excited about Robert Farris Thompson’s ideas and she inspired me to read African Art in Motion after her course was over.”

Banes suffered an incapacitating stroke in 2002. Her last collection, Before, Between, and Beyond: Three Decades of Dance Writing was compiled and edited by her then-assistant Andrea Harris. It has two forewords that sum up Banes’s prodigious output, one by historian Lynn Garafola, and the other by New Yorker critic Joan Acocella.

Garafola: “By the 1990s the hip, young critic of the mid-1970s had become a hip, mature academic. Yet . . . she continues to write in plain English. Her sentences move across the page with energy, and for all her interest in ideas, she still wants the reader . . . to see the movement and experience it imaginatively…More than any other critic or scholar of dance, she belongs to her time, writing with the voice of the Zeitgeist.”

Acocella: “Underneath it all…is an anarchic spirit, walking on the wild side. And joined to it is exactly what one needs with it: scholarship, moderation, wisdom.”

There aren’t many traces of Banes in person on the internet, but Walker Art Center posted this wonderful conversation between her and Yvonne Rainer in 2001. The occasion was Baryshnikov’s PastForward project, which gathered several of the Terpsichore artists together for a tour.

For her naming and framing of new forms, and for the breadth and depth of her writing about dance as part of a complex world, Banes garnered lifetime achievement awards from the Congress on Research in Dance, the Society of Dance History Scholars, and the New York Dance and Performance Awards (the Bessies). When Terpsichore was translated into French by Denise Luccioni, it won the prize for the best dance book of 2003 in France.

Brungard says, “When I read her now, I hear her voice coming through the page, I hear her excitement behind the words. I have that same sense of inspiration I had when she was my teacher. I’m glad her personal voice comes through in her writing because it’s a way that people can have her as a teacher now.”

There is another way her teaching lives on: choreographer Li Chiao-Ping, a protegée of Sally’s at University of Wisconsin, has just been awarded a named professorship and has chosen to be named the Sally Banes Professor of Dance.

Here are a few of the 51 comments from dance scholar Mark Franko’s Facebook page after he announced that Banes was in hospice care:

Millicent Hodson: “Sally was the star journalist of her time in Soho NYC & a generous colleague.”

Dena Davida: “She will be leaving us with an epic body of insightful and radiant texts about our dance world.”

Jennifer Fisher: “Such a beautiful writer, and her work retains relevance over time.”

Donald Byrd: “Sorry to hear this news. I admire her.”

Ginnine Cocuzza: “Bright flame.”

¶¶¶

Disclosure: Sally and I were friends and colleagues. She conferred with me when writing Terpsichore; I invited her to write for SoHo Weekly News when I was editor of its “Concepts in Performance” page. After I handed the editorship of “Concepts” off to her in 1978, she edited my reviews. She wrote about my choreography a couple times, and I invited her to be part of my Bennington College Judson Project while she was writing her dissertation on Judson Dance Theater. I was in her performance piece-in-progress, Sophie Heightens the Contradictions in 1983, in which I played Sophie, a young Communist ballet dancer at the time of the Paris commune. And Sally appeared in a video for my performance Standard Deviation in 1984. I contributed to Reinventing Dance in the 1960s: Everything Was Possible (2003), the collection of personal reminiscences she edited.

¶¶¶

Featured 12