I’m starting a new series devoted to outstanding dance artists who have either faded from memory, had too short a dance life, or are left out of the dance books. I’ve been around long enough to witness absolutely unique people getting lost in the mists of time. I plan to add one person each month, drawn from the long list of people I’ve either seen myself or heard about and am curious about. Some of them were praised at the height of their careers but gained no permanent traction. Others were never fully recognized for their contributions. This series is an attempt to rebalance the books—the dance books.

First up is Eleo Pomare. Recently, when I mentioned him in my dance history class, no one knew his name. But when the students saw a clip of his work on YouTube, they said, “Why haven’t we heard of him?”

¶¶¶

Eleo Pomare was one of New York City’s unforgettable dance artists of the 1960s. When I saw him in a DanceMobile show (basically a flatbed truck that toured inner-city neighborhoods), he performed a drastic solo from Over Here (1968). While the American anthem was playing, Pomare was mimicking retching. It was so real, so alarmingly visceral, that you could practically see his innards thrusting up through his throat. This remains the most extreme public response to our nation’s injustices I’ve ever seen—long before Colin Kaepernick took the knee.

Pomare was a prolific choreographer whose work was too raw for prime time. As Anna Kisselgoff wrote in The New York Times, “Eleo Pomare’s dances always have a special gutsy quality.” His performances were hyper-realistic; indeed he was accused of being “too real.” Although he wasn’t invited to go on State Department–sponsored international tours like Alvin Ailey or to choreograph Broadway musicals like Donald McKayle, he kept making dances—118 in all. His courage and imagination were inspiring; his febrile physicality was startling. As dance historian Katrina Hazzard Donald says in the PBS special Free to Dance, Pomare “imparts a new validity to Black life in much the same way that Malcolm X does.”

Pomare was a prolific choreographer whose work was too raw for prime time. As Anna Kisselgoff wrote in The New York Times, “Eleo Pomare’s dances always have a special gutsy quality.” His performances were hyper-realistic; indeed he was accused of being “too real.” Although he wasn’t invited to go on State Department–sponsored international tours like Alvin Ailey or to choreograph Broadway musicals like Donald McKayle, he kept making dances—118 in all. His courage and imagination were inspiring; his febrile physicality was startling. As dance historian Katrina Hazzard Donald says in the PBS special Free to Dance, Pomare “imparts a new validity to Black life in much the same way that Malcolm X does.”

For this article, I have relied on two main sources: A cover story in the November 1968 issue of Dance Magazine and a recent phone interview with Dyane Harvey-Salaam, the well-known dancer who started working with the Eleo Pomare Dance Company in 1969. A complete list of sources is at the end.

Beginnings

Born in Colombia, South America, Eleo Pomare sailed with his father, who was of Haitian and French extraction, to join his mother in Panama when he was six. This was during World War II, and his boat was torpedoed by the Germans. Although he was rescued, his father was never found. The trauma of that tragedy gave him a dread of water for the rest of his life. When he was ten, he emigrated to New York to live with his mother.

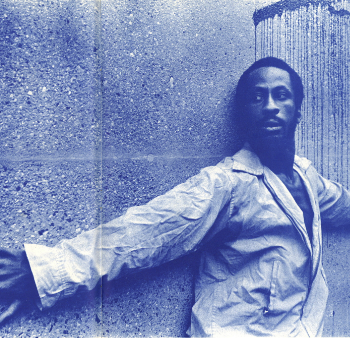

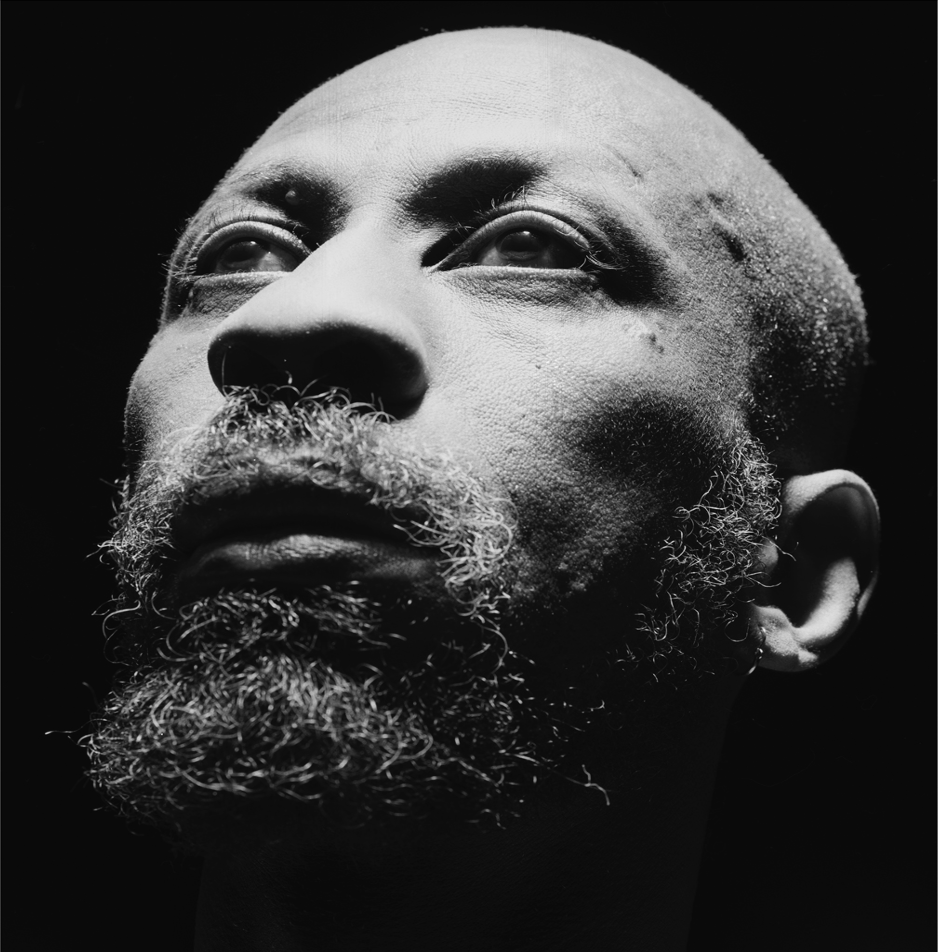

Pomare in photo shoot with David Fullard, courtesy Jill Williams

Pomare was always drawn to music. When he reached Harlem, the sounds coming out of churches reminded him of Carnival back in Colombia and Panama. About attending the church events, he said, “At the time I didn’t realize I was studying theater.”

Pomare enrolled in the High School of Performing Arts for its theater program, but after a year he switched to dance. Fellow student Cora Cahan (co-founder of The Joyce Theater and now president of Baryshnikov Arts Center) remembers him vividly: “He was true to his own voice at an early age. He couldn’t conform; it wasn’t in his DNA. He was highly original.” He studied composition with Louis Horst; he also sought out teachers of color, attending the New Dance Group to study with Asadata Dafora and Pearl Primus, and also studied with Syvilla Fort and José Limón. After he graduated in 1958, he co-started a small dance company with fellow student Dudley Williams.

In 1962, he accepted a scholarship to study with Kurt Jooss in his school in Essen, Germany. But he hated it there, likening the school to “a convent or prison.” He started choreographing with students from the school, which rubbed Jooss the wrong way, and he was expelled. He moved to Amsterdam with his dancers and performed his experimental work in the Netherlands, Sweden, and Denmark, receiving good reviews.

In 1963, fate intervened. As the Civil Rights movement in America heated up and the March on Washington approached, the writer James Baldwin, a good friend of Pomare’s, called him. “Eleo,” Baldwin commanded, “you are going to be there.”

He was ready to leave Europe anyway. “Eventually, I felt Europe wasn’t for me,” he said in 1968. “A Negro dancer is to them a ‘wild thing,’ exotic.” On a later occasion he explained his disaffection further: “I believed the myths that one had to study in Europe to be really educated, and that Europe was more sensitive to Black people. I was looking for a place to work where my complexion didn’t come before my product.”

Artistic Range

The March on Washington, where Martin Luther King, Jr. gave the famous “I have a dream” speech, galvanized Pomare to put Black life forward in his work. His work Blues for the Jungle (1966) included a preacher, a couple involved in domestic abuse, a prison inmate dreaming of freedom, a prostitute, a cop, a nun, and, most famously, a junkie. Pomare performed the junkie himself, writhing, convulsing, desperate for a fix, basically self-destructing—in the most riveting way. According to Thomas de Frantz, Blues for the Jungle “included a cast of desperate characters who spilled from the stage as they shouted slogans and physically confronted the audience, accusing them of complicity in the construction of the American ghetto.” (The beginning of this segment of “Free to Dance: Episode 3: Go for What You Know” shows part of Jungle including “Junkie.”)

Narcissus Rising

His signature solo, Narcissus Rising (1968), was possibly even more harrowing. Pomare, as an S & M biker, wearing a leather jockstrap, bare chest, sunglasses and rakish cap, revved his imaginary motorcycle, declaring his right to be a rebel. The character, whom we might define today as intersectional, was described by Don McDonagh as “menacing”—until he is hunted down by police searchlights.

Spanning five decades, Pomare’s work explored many other themes as well. Some, like Sombras (1980) and Conaqua (1987), were based on his Hispanic heritage. Others were based on literature, like Still Here (1982), inspired by a Langston Hughes poem, and Tabernacle (1989), inspired by Baldwin’s The Fire Next Time. Still others were mostly musical, like Back to Bach (1983).

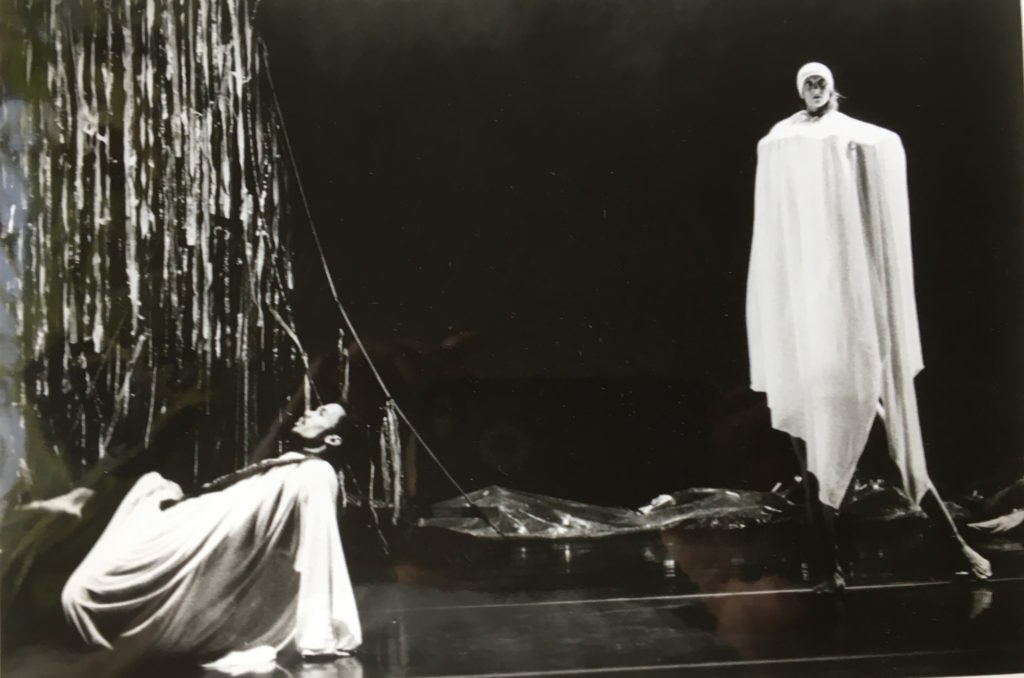

Conagua (1987) with , L: Stanley Joseph and R: Maxine Steinman, photo by David Fullard, courtesy Harvey-Salaam and Martial Roumain

A more hard-edged portrayal, along the lines of Blues for the Jungle, was High Times (1967). McDonagh recalled that in the “Up Tight” section of this ballet, “a snarling speakeasy atmosphere vividly came alive to convey skillfully the unhappiness of the people trapped within.”

And then there was the high drama of the literary sort: Las Desenamoradas (1967) an interpretation of Garcia Lorca’s “The House of Bernarda Alba.” About this enduring work, Dyane Harvey-Salaam says, “This situation deals with the human condition, how human beings interact with one another. Everybody in the piece is suffering, except the suitor who married into the family. All of the women are frustrated, and you get a chance to dig into personalities and interactions.”

About his grittier work, Harvey-Salaam says, “It doesn’t bother me to depict these powerful atrocities because if we don’t show them, if we don’t dig into them, how will we ever be able to appeal to anyone else’s humanity?”

But she also appreciates the gentler, imagistic side of her mentor’s oeuvre: “Along with all the global consciousness, the human suffering, the struggle against injustice, he was very intrigued with the beauty of life itself.” She described scenes from De la Tierra (1975), which is based on images from his youth: “He created a cricket by using dancers with poles as the legs,” recounted Harvey-Salaam. “A little boy was dancing around the cricket, searching for his voice. In another scene I portrayed a little girl playing/dancing in the street as a funeral passed by. These were haunting yet beautiful images.”

Pomare was ahead of his time in exploring gender. As mentioned, Narcissus Rising claimed his right to be Black, queer, and self-defined. In “Ode to Prophet Jones,” which was originally part of Radiance of the Dark (1969), he played a prophet in drag. But he also knew how to give women dancers their power. McDonagh, writing in The New York Times, described the solo Hex (1964) as “a study of a woman bursting with venom and magic.”

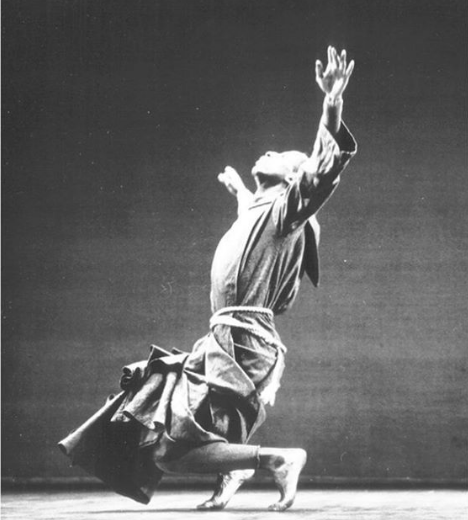

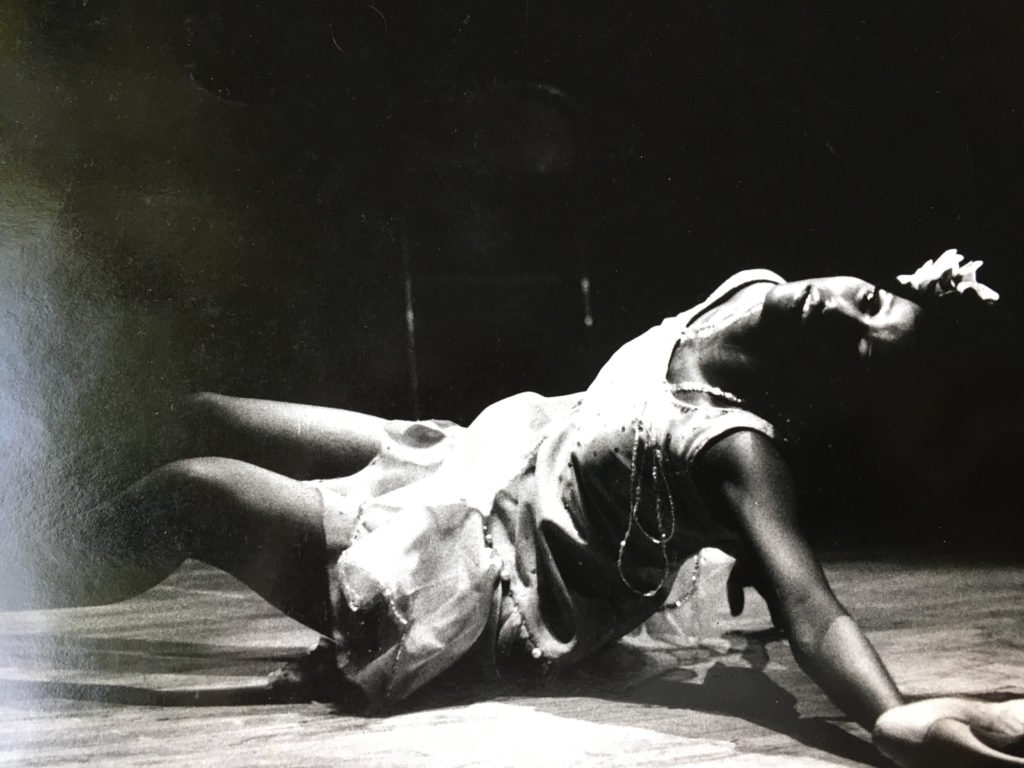

Pomare in Cantos from a Monastery (1956)

The music for Pomare’s choreography ranged from Coltrane to Vivaldi, Steve Reich to a Congolese Mass, Miles Davis to the Edwin Hawkins Singers.

Other companies that have performed Pomare’s works include Dayton Contemporary Dance Company, Philadanceo, the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater, Cincinnati Ballet, the Cleo Parker-Robinson Dance Company in Denver, Alpha and Omega Dance Company in New York, and companies in Holland, Norway, Australia, Taiwan, Canada, and Brazil. He has mounted works for students at Southern Methodist University, Howard University, Florida A&M, The Ailey School, and Hofstra, where Harvey-Salaam has been an adjunct for years.

Pomare in South Africa, with Diane Johnson of African Arts Fund, 1992, photo by Anthony Rodale

In the Studio

Elizabeth Dalman, an early dance collaborator in Pomare’s European company (Dansgroep Eleo Pomare) in the ’60s, said this about working on his piece Gin.Woman.Distress (1966): “My body was in such turmoil, and he would say, ‘Push the leg more, the arm more,’ … the shape being the feeling for the viewer.”

In the early 70s, as Harvey-Salaam told me, “The Black Arts Movement was on fire. Everyone was finding their voices, developing their expression.” It was in this context that she started working with Pomare. “He made me think about what I was doing. He made me investigate what kind of energy I needed to achieve the movement or the shape or the concept.” She watched him nurture other dancers too. “Depending on what you brought to him, he would adapt and adjust and then go full steam ahead on you. He did that with your mind as well as your body.”

In 1972, the year after Ailey choreographed Cry for Judith Jamison, Pomare made Roots for Lillian Olubayo Coleman. A fifteen-minute solo in three sections, it started in Africa with African sculptures, went to the song “Strange Fruit” with Billie Holiday singing about the horror of lynchings, and ended up with Nikki Giovanni’s poem “The Great Pax Whitie,” an indictment of systemic racism. For Harvey-Salaam, who stepped into the solo later, Roots made a statement: “We have to honor ourselves. We have to see life for what it is and acknowledge our greatness, our ability to survive, achieve, and thrive.”

Lillian Olubayo Williams in High Times, photographer unknown, courtesy Havey-Salaam and Martial Roumain

Angry or Alert?

Although Pomare was often called the “angry Black man of dance,” his own preferred adjective was “alert.” He was alert to the ways in which the Black community was marginalized. He was also alert to how some white critics tried to marginalize him. When asked to respond to critics who called his work “too real” or “too undisciplined,” he replied, “Whites see things only in terms of their own values — they feel too little for the Negro.” As for discipline, “How many critics really understand the discipline it takes to erase all white influences, and yet dramatize precisely the world the Black artist is struggling to escape from?”

Pomare had no wish to seduce or appease a white audience. “I don’t create works to amuse white crowds,” he said in 1968. “Nor do I wish to show them how charming, strong, and folksy Negro people are—as whites imagine them—Negroes dancing in the manner of Jerome Robbins or Martha Graham. Instead I’m showing them the Negro experience from inside: what it’s like to live in Harlem, to be hung-up and uptight and trapped and Black and wanting to get out. And I’m saying it in a dance language that originates in Harlem itself.”

The novelist Toni Morrison has also said that she did not write for a white audience. Of course, Morrison’s novels do attract many white people. So too did Pomare’s forceful and imaginative works.

In “Free to Dance,” he stated clearly his view of the artist’s role. “What the choreographer should do is to instigate or to be forecasters of things to come.”

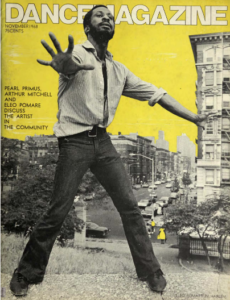

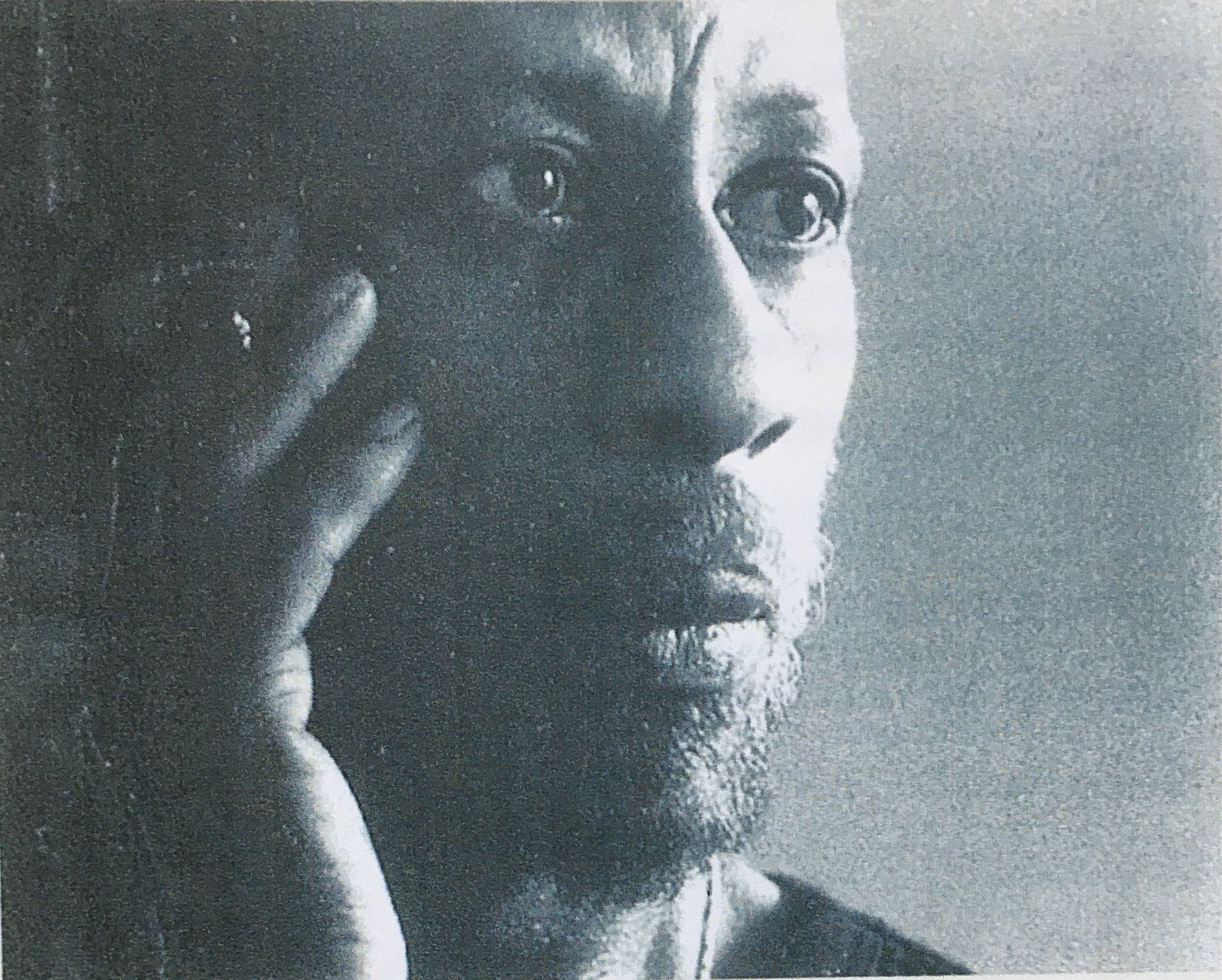

Pomare, 1968, photo by Sigrid Estrada for Dance Magazine

This attitude sometimes caused controversy. At the Adelaide International Festival for the Arts in 1972, he railed against being marginalized by the choice of venue, making headlines. In the meantime, his main dancer, Carole Johnson had taught classes in advance of the performance to a group of Aboriginal dancers. To the dismay of the white presenter, he gave out free tickets to these indigenous dancers. While the white audience was indifferent, it was his new friends who really took to the work.

Creativity in All Directions

Harvey-Salaam notes how Pomare defined his art. At school lecture-demonstrations, he would explain to the children, “I’m a choreographer. A choreographer uses bodies to paint pictures to tell stories.” She recalled that his drive for artistic expression was constant and varied. When he wasn’t choreographing—or painting or writing poems—he could be stringing beads, sewing a shirt, or cooking a special dish—or he’d say, “Let’s go to the museum.” (An example of his paintings can be seen here.)

The poet in him came out when describing his own dancers. In 1966, two of his longtime female dancers performed in his Gin.Woman.Distress. to songs by Bessie Smith. They were Elizabeth Dalman, a white dancer from Australia, and Carole Johnson, an African American who later stayed in Australia to work with the Aboriginal dancers. “When Lizzie does it, it’s as if she swallows the heat and you feel that the heat is burning from the inside out, that she’s not going to let it explode. Carole ices it; she’s like a block of ice until you see the cracks when it starts melting.”

In the 1980s and ’90s Pomare’s home base was the Vital Arts Center on 13th Street and Fifth Avenue. When he moved to a larger venue, with four or five studios, he presented work of younger artists like Harvey-Salaam. Pomare and his group kept performing at venues like Marymount Manhattan Theater, Hunter Playhouse, the DanceMobile, and the Delacorte. Sometimes the program included works by other choreographers like Anna Sokolow and George Faison. And he taught in many public schools. In this video where he is giving a lecture-demonstration, you can get a sense of how spontaneous and irrepressible he is, and of his unique, androgynous way of moving. He is showing the ditty bop walk of Harlem, and saying, “I want my dancers to be people.”

Morning Without Sunrise, with Charles Grant, photo by David Fullard

Pomare never accepted being wedged into any racial or cultural hierarchy. Even when he was invited to South Africa by Nelson Mandela in 1992, he did things his own way. Harvey-Salaam recalls, “He went to South Africa and was supposed to teach in Soweto. They told him they wanted him to teach ballet and he said, ‘No that’s not going happen. I’m going to see what the people move like. I’m going to have them teach me how they move. I’m not interested in imposing a European model. I want to give them tools to explore their own language.’ When he came back he created Morning Without Sunrise (1986), a work to music by Max Roach that was dedicated to Nelson Mandela.

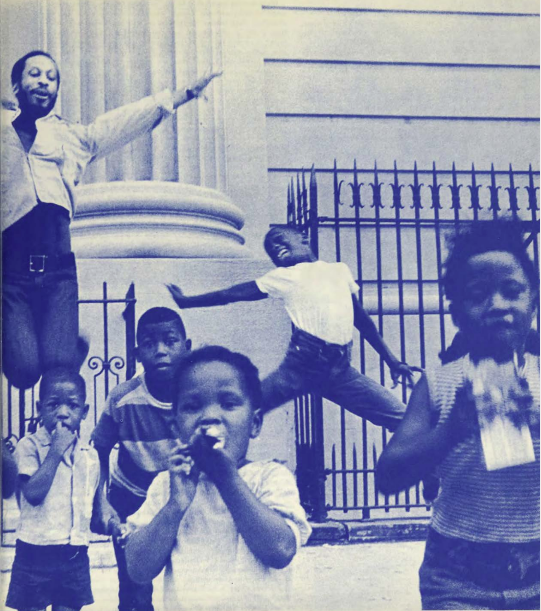

He was also committed to community projects and co-founded the DanceMobile series. Sponsored by the Harlem Cultural Council, this flatbed truck took modern dance performances into underserved communities in the ’60s and ’70s. As its first artistic director, Pomare planned programs that would appeal to children who had never seen dance.

Pomare with children in Harlem, photo by Sigrid Estrada for Dance Magazine, 1968

Pomare remained friends with James Baldwin. According to Harvey-Salaam, “Whenever Eleo mentioned James Baldwin, his heart was warm. He had a deep, deep brotherly camaraderie with Mr. Baldwin. I believe they were kindred spirits in terms of how they used language and how they were deeply committed to discussing this problem with global injustice. They both had had experiences in the U.S. growing up in Harlem, feeling displaced, going to Europe and hoping that this would be the place where they could simply do their art, but realizing that . . . this is the place where racism began, the seeds of racism.”

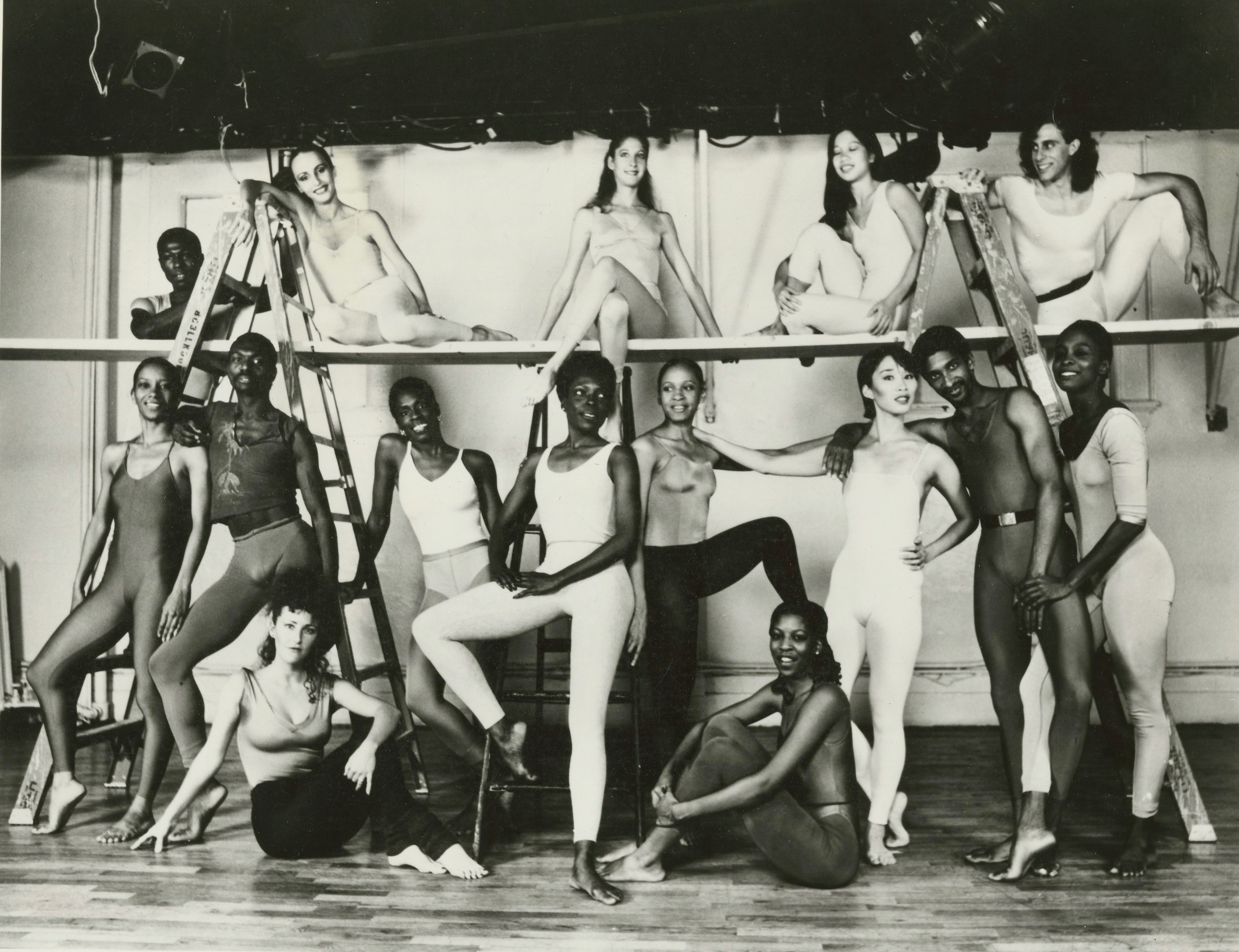

Eleo Pomare Dance Company in an undated publicity shot by David Fullard, courtesy Anthony Rodale

Sparking the Next Generation

Always outspoken, Pomare was the boldest voice on a panel presented by American Dance Festival’s landmark project The Black Tradition in American Dance, in 1988. He posed a question—“What are we going to do now?”—that sparked at least one younger Black artist into action. I had read that Halifu Osumare, author of Dancing in Blackness, was influenced by his question that day, so I asked her in an email to clarify, and she did:

As he was often called “the bad boy” of New York Black concert dance, he was never afraid to explore the underbelly of New York and its reflection of systemic racism and homophobia. One need only revisit his choreographic works Blues for the Jungle (1966) and Narcissus Rising (1968). His artistic themes reflected his vision of the world: one had to challenge injustice and call it out directly. Therefore, when all of the choreographers in ADF’s historic Black Traditions in American Dance project were acknowledging historic racism and attempted invisibilizing of Black dance artists, he wanted to focus on contemporary activism—what could be done at the time to ensure the field of dance was challenged and changed. Although he recognized ADF’s effort and was glad to be a part of the project with his Las Desenamoradas set on Dayton Contemporary Dance Theater, he felt more needed to be done.

When he challenged the ADF choreographers and panelists to think about “What are we going to do now?,” I knew my charge. I felt I had to make a major statement about the then young Black choreographers’ recognition and how they were perceived. Hence, I began to work on a mission statement and the first grant to the NEA for Black Choreographers Moving Toward the 21st Century, a national dance initiative that premiered in 1989 at Theater Artaud in San Francisco and Royce Hall on the UCLA campus in Los Angeles. My project continued for five years under the presentation of Theater Artaud, First Impressions Performances (LA), and later Sushi Performance Gallery (San Diego). Tens of artists were showcased and appeared on panels, such as Jawole Willa Jo Zollar, Bill T. Jones, Ishmael Houston-Jones, Nia Love, Lula Washington, Cleo Parker Robinson. I consider it to be the Black Lives Matter initiative in dance during the last decade of the 20th century.

Portrait by Anthony Rodale

Recognition

Although the name Pomare is not imprinted on our dance-history brains, he did receive accolades in his time. New York City Manhattan Borough President David Dinkins (later to become mayor) declared January 7, 1987 “Eleo Pomare Day” in honor of his contributions to the city’s cultural life. In addition to the John Hay Whitney Fellowship that sent him to Germany, the young choreographer received a Guggenheim Fellowship, regular funding from the National Endowment for the Arts, and numerous other awards. The Alpha Omega Theatrical Dance Company celebrated him with a Salute to Living Legends in 1993, and the International Conference of Blacks in Dance bestowed him with an Outstanding Achievements in Dance Award in 1994. The American Dance Guild gave him a Posthumous Lifetime Achievement Award in 2018.

Dyane Harvey-Salaam in Hex, 2018, photo by Yi-Chun Wu, courtesy American Dance Guild

Continuing On

In 2001, the Alpha Omega Theatrical Dance Company presented Narcissus Rising with a woman, Donna Clark—the biker dude turned to biker chick, complete with boots, G-string, and oiled thighs. Karyn D. Collins, reviewing in Dance Magazine, characterized Donna Clark’s performance as “all defiant glare and stalking feminist power.” This was quite an achievement considering some critics had claimed that this solo relied so much on Pomare’s own magnetism that it might not survive a transfer to another dancer.

In the 12 years since his passing several of his works have been reprised. In 2009, Hex and Roots were performed at a symposium in Paris sponsored by the French Ministry of Culture. Harvey-Salaam and Robin Becker remounted Des Desenamoradas on Hofstra students in 2018.

Also in 2018, Loris Beckles, who had danced with Pomare for 18 years, mounted a tribute concert called Pomare Plus, with his group, Beckles Dancing Company. The program included a selection of Pomare’s solo works.

Longtime Pomare dancer Carole Johnson, who had stayed in Australia to teach indigenous peoples, co-founded of Bangarra Dance Theater in 1989. According to Rachel Fensham in “Breakin’ the Rules: Eleo Pomare and the Transcultural Choreographies of Black Modernity,” this company carries on some of his influence.

Looking back, Harvey-Salaam says, “Eleo wanted us to see ourselves in all of our pain and beauty, and to let his audiences know, ‘I see you, we are together in this.’”

Portrait by David Fullard, courtesy Jill Williams

¶¶¶

Special thanks to Dyane Harvey-Salaam, Cora Cahan, Jill Williams, Anthony Rodale, Halifu Osumare, Martial Roumain, and David Fullard. Thanks also to Rashida Ismaili for factual corrections given on August 3.

Sources:

- Interview with Dyane Harvey-Salaam, July 14, 2020

- Ric Estrada, “Three Leading Negro Artists and How They Feel About Dance in the Community: Eleo Pomare, Arthur Mitchell, and Pearl Primus, Dance Magazine cover story, November 1968

- Anna Kisselgoff, several reviews in NY Times, and the obit

- Rachel Felsham, “Breakin’ the Rules: Eleo Pomare and the Transcultural Choreographies of Black Modernity” Dance Research Journal, April 2012

- Jennifer Dunning, “Eleo Pomare Deals with Man’s Inhumanity to Man” New York Times, Nov. 13, 1983,

- Don McDonagh, “Eleo Pomare Group Dances in Brooklyn,” New York Times, November 13, 1967.

- Don McDonagh, The Complete Guide to Modern Dance

- Don McDonagh, “Pomare Dance, Hushed Voice, Out of the Past”

- Thomas DeFrantz, Dancing Revelations

- Manuel Mendoza, “Work of ‘angry black man’ of midcentury modern dance revived in Dallas,” The Dallas Morning News, April 12, 2018;

- A List of Eleo’s Works and Achievements

- “Free to Dance, Episode 3, Go for What You Know,” produced by PBS and ADF

- Richard A. Long, The Black Tradition in American Modern Dance (based on a project of the American Dance Festival) Rizzoli, 1989

- Karyn D. Collins, “Pomare Power Enlivens Omega Evening,” Dance Magazine, October 2001,

- The History Makers, interview with Eleo Pomare, April 18, 2007

- Julinda Lewis-Ferguson, entry on Eleo Pomare in the International Dictionary of Modern Dance

Unsung Heroes of Dance History 4