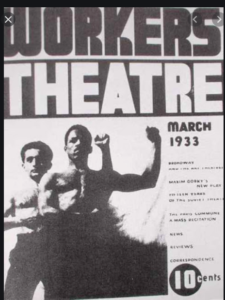

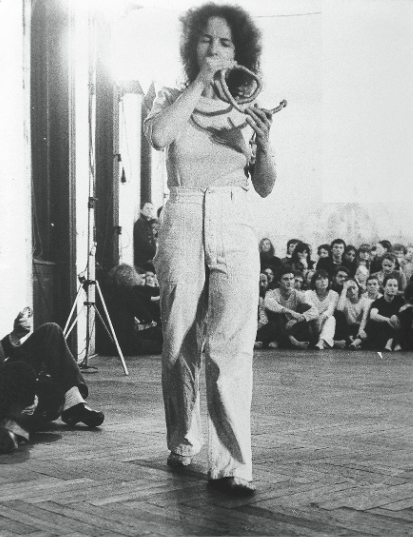

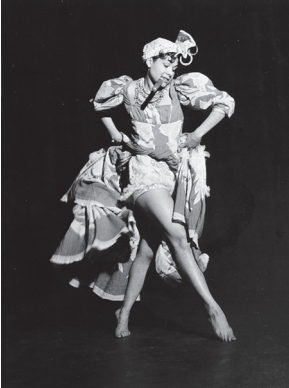

Forti with makeshift horn, Vienna, 1978,

ph Robert Fleck via The Box L.A..

Simone Forti is an inventor of forms. In her performances, the elements of movement, sound, and objects commingle into a new hybrid. Her art embodies both the conceptual strength of minimalism and the curiosity of exploratory improvisation, with her own sly wit thrown in to ensure a dose of radical juxtaposition.

Forti’s great gift is simplicity—a divine, earthy simplicity that can touch onlookers to the core. She possesses an intuitive sense of what is artistically essential at each moment of performance. About the 1960s, the decade in which she forged her aesthetic, she has written, “Back then, making a piece was like brushing away all the sand and debris to reveal one stone.”[i]

A singular force in the art of our times, Forti was the bridge that connected Anna Halprin’s nature-based improvising on the West Coast with the chance methods of John Cage via Robert Dunn in Manhattan. It was Dunn’s composition classes at Merce Cunningham’s studio that led to the revolutionary Judson Dance Theater. Forti’s ingenious concepts and daring dancing inspired Judson co-founders Yvonne Rainer, Steve Paxton, and Trisha Brown to be rigorous in their rule-breaking. She was a major influence, a spirited catalyst, in the formation of Judson Dance Theater, and thus postmodern dance, a role for which she has not been fully recognized.

Forti is known as a master improviser in the dance world. She’s written about what it feels like to be swept up in the “dance state.” By this she means either “that mysterious response to the music”[ii] or “a certain gear…an activation of motor intelligence.”[iii] But from the start she has identified as simply an artist—or a “movement artist”—rather than specifically a dance artist, having no wish to divide the arts into separate categories. In 1961, she mixed disciplines in a way that was natural for her and momentous for the times. Her “dance constructions,” as she called these pieces, merged object and motion in a way that made each essential to the other, thus achieving the desired “one-thingness” of minimalism. In recognition of her achievement in the art world, the Museum of Modern Art recently acquired her dance constructions (more about that later).

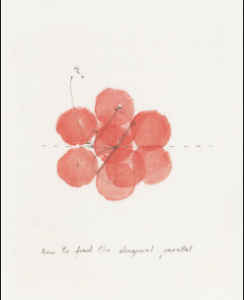

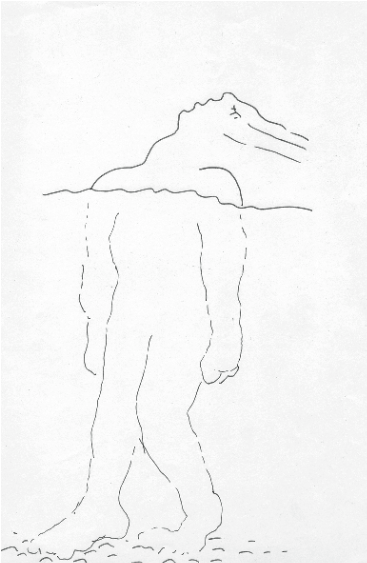

Red Illumination drawing, 1972

Yet the source of her decisions, rather than the theoretical reasoning of male minimalists, has always stemmed from her emotional needs. Her subsequent work—the animal studies, the “illuminations” with musician Charlemagne Palestine, the news animations, the garden journals, the drawings, and the two books she has written—continue to elude categories. In today’s cultural climate where many artists, educators, and thinkers try to move beyond binary thinking, Forti’s embrace of holistic process remains a quintessential model.

An Arts Childhood

Born in 1935, Forti counts writers and composers among her extended family. One uncle, an art critic, was a friend of Giorgio De Chirico, and another was a composer who wrote film scores and composed music for the guitarist Andrés Segovia.[iv] But her immediate family were refugees. When she was four, they narrowly escaped the Holocaust. Having fled Mussolini’s Italy to stay in non-aligned Switzerland,[v] the Fortis lived in Bern for six months, during which time Forti’s mother (Milka Forti) fell gravely ill. On the way to visiting her mother in the hospital, Simone remembers going to the zoo and watching the bears. This was the first time of many that watching animals in motion became a source of self-soothing. (The Swiss, Forti points out, regard the bear as a protective animal.)[vi]

She was five when the family finally settled in Los Angeles. At eight or nine, Forti was sent to dance class because she had flat feet. She took lessons in ballet, tap, Mexican folklorico and what was then termed “oriental” dancing, the latter being her favorite because she liked the “snaking arms.” At home, when she and a friend danced to records of Edvard Grieg’s Peer Gynt, “We’d whip up a storm.”[vii] In Los Angeles, she again visited the zoo, often drawing the animals she observed.[viii]

At Fairfax High School, when she was given a choice between gym and modern dance, she chose the latter. “The teacher had us creating our own dances with a lot of improvisation, with the records we wanted to bring in. There was the matter of just cutting loose and letting movement come out.”[ix]

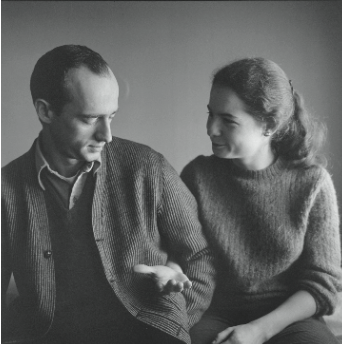

Robert Morris and simone Forti,

c. 1957, ph © estate of Warner Jepson 2017. Museum of Performance + Design, San Francisco.

She took Saturday art lessons at Jepson Art Institute in Los Angeles and grew up surrounded by art books. Her favorite painters were Joan Miro, Piet Mondrian, and Francisco Goya.[x] But she also loved surrealist films and often rode her bike to the Coronet movie theater. “My first awareness that you can work with anything that captures your imagination is from films—Cocteau films, early Renoir.”[xi] (The experimental dancer/filmmaker Maya Deren was also on that list.[xii]) Forti not only responded to the moving pictures, but she dug the style flaunted by the sandal-soled denizens who mingled in the lobby. “I was going to be a Bohemian girl,” she pledged to herself.[xiii]

At Reed College in Portland, Oregon, where she had planned to study biology and sociology, Forti met visual artist Robert Morris. In 1955 they dropped out, moved to San Francisco, and got married.[xiv] (She completed her BFA at Hunter College in New York in 1965.) At the time, Morris was making abstract expressionist paintings that required physical agility to apply paint to canvas. He encouraged his new wife to start painting too; he built a palette table for her and showed her how to stretch canvases.[xv] Typical of Forti’s, shall we say, unorthodox use of the body, she would sometimes “start a painting by taking a nap on a freshly stretched canvas.”[xvi]

Working with Anna Halprin

For Forti, encountering Anna (then Ann) Halprin in 1955 nurtured all her emerging movement and art interests. At first she took classes at the Halprin-Lathrop Studio in San Francisco, which were based on modern dance techniques. But when Halprin’s interests shifted toward improvisation, Forti was thrilled. The moment of that particular awakening occurred in a class taught by a top Halprin student:

One evening, instead of the usual technique class, one of Anna’s senior students, A. A. Leath, taught a dance improvisation class. He had us work with the idea of upwardness. I clearly remember a moment of deep and joyful involvement, lying on the floor, every cell of my body reaching upwards. And from the edge of the room I saw A.A. make a gesture as if to cast a fishing line to reel me in.[xvii]

Forti was invited by Halprin to study at her mountain

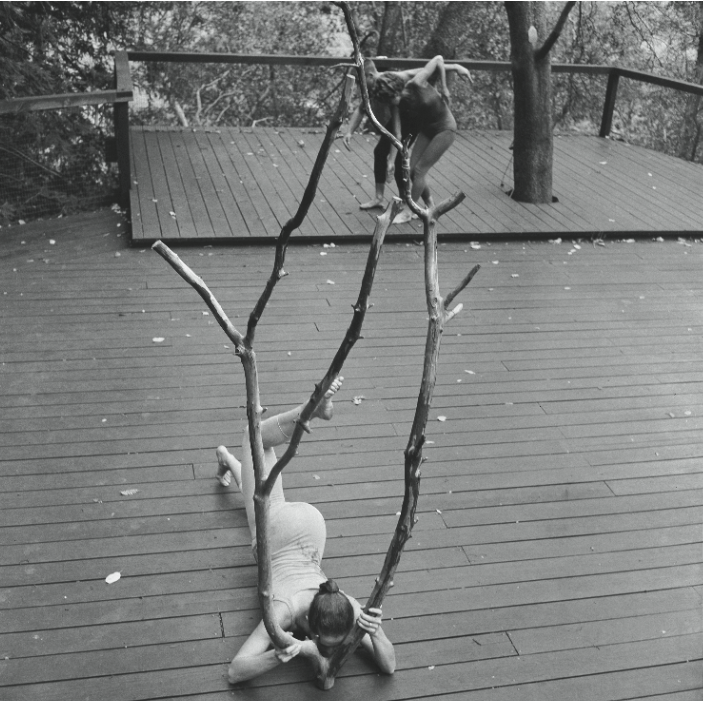

Halprin’s Branch dance, Kentfield, CA, c. 1957: Forti, foreground, Halprin & A.A. Leath, ph © estate of Warner Jepson 2017, MPD.

home studio, where sessions on the outdoor deck involved keen observation and concentration. The younger dancer felt it was a “tremendous gift” to be working with her mentor at a time of change.[xviii] “It was all very new,” she said about the work with Halprin. “It was her honeymoon with improvisation.”[xix]

The focused explorations led to specific revelations about the inter-connectedness of the body. “If you pick up something heavy, the work of the legs changes,” Forti noticed. “If you swing an arm, the whole body changes. We’d be improvising around a point of reference, and it would be joyful.”[xx]

She often quipped that improvising was physically like making expressionist paintings minus the baggage of the actual canvas.[xxi] From the beginning, Forti conceived of her body as part of the art.

The somatics practitioner June Ekman, who started studying with Halprin in the summer of 1955, was struck by Forti’s dancing right away. “Her quality was sensuous; it was organic—in a way, fearless.”[xxii] She also observed that Forti had already earned a favored place in the Halprin constellation:

It seemed to me that Simone was quite established. Anna was crazy about her. Anna loved her.…Every time we were on the dance deck, a lot of attention was paid to what Simone was doing. Her quality was sensuous, it was organic—in a way, fearless. Simone was very lyrical and Anna was not. Anna had a strong, attenuated body, wonderful in a Hanya Holm way. She did a lot of arcing and swinging. Simone didn’t have bones; she was very flexible.[xxiii]

Ekman felt that Halprin, while breaking away from modern dance and reaching toward a more functional use of the body, saw in Forti a dance artist who embodied the new path.

For her part, Forti found resonance in the Bauhaus aspects of Halprin’s approach as it reminded her of Saturdays at Jepson Art Academy.[xxiv]

She would have us work with elements like the negative space between two dancers…Or we would explore conceptual elements: momentum, weight, line. She wouldn’t show us movements, but would say, “We’re going to work with fast and slow for an hour, and then we’ll show each other interesting things that we found”…And then Anna might say…“What was interesting about this?” or, “You could go deeper into that.”[xxv]

Halprin immediately trusted Forti. She cast the newcomer alongside the senior members of the San Francisco Dancers’ Workshop, and she sent her to teach children’s classes. They were on the same wavelength in terms of observing nature—nature as in landscape as well as the nature of the human body. They also shared a willingness to try new things. Words came into their work through John Graham, a longtime Halprin performer who had had theater experience. While experimenting with vocalizing and movement, Forti realized that words could be used not only to illustrate movement but also to oppose it:

Maybe you could be doing very watery movement, very languid, soft undefinable movement. At the same time you could be describing the splinters of glass of a broken window. So we were juxtaposing very different qualities. It was a collage kind of aesthetic. We were working with nonsense and the kind of surprise to the imagination— non-sequiturs—and I think the more something would slightly unhinge our mind, the more delightful it was.[xxvi]

The “surprise to the imagination”—often involving the juxtaposition of two very different things to produce an unknown effect—is basically a Dadaist idea. According to Forti, Halprin also urged “that we should base our work in the experience of sensation. That has some roots in how California absorbed Zen—mainly from Shunryu Suzuki, whom all the beat poets studied with.”[xxvii]

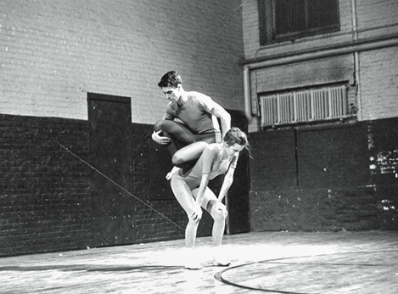

Halprin’s Four Square (1959), 1960: Forti and A. A Leath, MPD

Doris Dennison, a pianist who accompanied classes at the Halprin-Lathrop School, had worked with John Cage at the Cornish School in Seattle. Through that connection, Cage came to know and respect Halprin’s work.[xxviii]

Like Halprin, Cage had interests in both Zen and Dada. In the 1950s, he had attended lectures at Columbia University by D. T. Suzuki (no relation to Shunryu), who was instrumental in introducing Zen Buddhism to the U.S. Even before that, he’d attended a lecture at Cornish by Nancy Wilson Ross, who had experience in both Dada and Zen. With just a bit of dramatic flair, Kay Larson wrote, “As Ross made the spiritual link between Dada and Zen, Cage’s mind flew out of its nest.”[xxix]

Cage felt Zen was essential to his work as a composer and thinker, but he did not want people to think Zen was responsible for the controversial nature of his ideas. “What I do, I do not wish blamed on Zen.” At the same time he felt that Dada, as embodied by Duchamp, could leaven Zen. Conversely, he said that Zen had put “a space, an emptiness” into the ideas of Dada.[xxx] In other words, there were ways that the Dadaist sensibility and Zen beliefs meshed well.

In January 1960, Cage urged his student and colleague La Monte Young to contact Halprin. Young, on his way to becoming a major minimalist composer, brought stimulating experiences to Halprin’s workshop. Often they were about listening. Forti was impressed that Young was using “a single mass of sound that didn’t change over time but was very complex within itself.”[xxxi]

During this period Forti was reading her own mix of Zen and Dada: British Zen specialist Alan Watts, surrealist poet and artist Kurt Schwitters, and absurdist playwright Eugène Ionesco. All three writers reinforced her interest in the “surprise to the imagination.” While performing in Halprin’s work, Forti and her cohorts would sometimes veer off into nonsense. “We would set up something that seemed to make sense so that we could flip it and have it not make sense.”[xxxii] It might have been exactly this kind of humor that made Forti say later, “We were California kids. It was sort of surfer surrealism.”[xxxiii]

Breaking Away from Halprin, or The Call of Minimalism

Forti was passionately engaged in Halprin’s work as it evolved. What she learned was central to the future development of her own work: “to really trust the body, its intelligence and how it wants to move.”[xxxiv] She loved the freedom of improvisation but found herself waking up in the wee hours and pounding on the floor, perhaps to protest what she felt was an overdose of super-saturated improvisation.[xxxv] Plus, she was also frustrated by the nonsense aspect of the verbal portion. “I began to wish that I could say what I meant. I remember toward the end of my time there one evening shouting out, ‘Say what you mean! Say what you mean!’ ”[xxxvi]

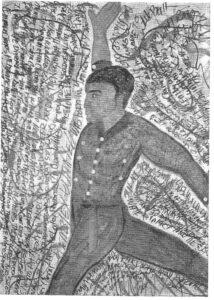

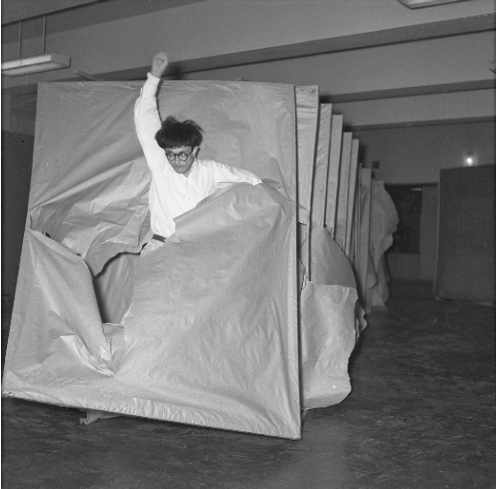

Saburo Murakami, “Passing Through,”1956, ph Osaka City Museum of Modern Art.

In 1958 or 1959, Forti saw an article in a magazine at Halprin’s studio about Japan’s radical postwar collective, the Gutai group. “They were doing single events, body events, jumping off of high places into mud, leaning logs up together and then crashing ’em down.”[xxxvii] One photo that imprinted itself on her mind depicted Saburo Murakami bursting through a series of large, framed paper sheets. His solo performance piece, Passing Through (1956), was a singular action that, even glimpsed in a magazine, made a strong impact. It seemed to be an antidote to what Forti called “a plethora of writhing” in her improvisational practice.[xxxviii] At the same time minimalism, with its demand for a single action, was gaining traction in the United States. Years later Forti wrote, “I prefer to see…some radical change take place in the course of the ‘piece’ rather than to see many varied shiftings.”[xxxix] Murakami’s bold action answered this wish. She experienced the call of minimalism as a response to the too-muchness (of physicality, emotional heft, and gesture) of abstract expressionism as well as to endless improvisation. “I still love abstract expressionism,” she told me recently, “but it was a little bit like when you’re drunk you want to lock your eyes onto something stable.”[xl]

In terms of style, Forti was crystallizing her own aesthetic of “plain beauty,” which did not always jibe with Halprin’s growing wish to produce finished dances. Forti recalled that while working toward a performance, Halprin would bring in a costume designer…“and the whole spirit of it changed. It would become much more theatrical.”[xli] She preferred the stripped down mode of rehearsal wear or street clothes.

For all these reasons, after four years, Forti needed to move on. Her husband, Bob Morris, wanted to go to New York to be around painters like Willem de Kooning and Mark Rothko[xlii] and she felt she needed a break. Together they moved to New York in 1959 (or perhaps early 1960[xliii]).

During the late summer workshop of 1960, when Forti returned to Halprin’s deck after having moved to New York a few months earlier, Halprin and Forti were observed arguing.[xliv] Perhaps it was inevitable that there would be tension between these two women, both at an early stage of becoming giants in the field. However, looking back on her time with Halprin, Forti said, “I feel that whether or not I had stayed with her vision, I really got a sense of what it is to have a vision.”[xlv]

Arriving in New York: Cunningham, Cage, Dunn

When Forti hit New York she felt alienated from the natural environments she loved. “It was like a maze of concrete mirrors. It was very depressing. I remember how refreshing and consoling it was to know that gravity was still gravity. I tuned into my own weight and bulk as a kind of prayer.”[xlvi]

One day, after a Cunningham technique class that Forti could not (or would not) absorb, Steve Paxton, then a member of the Merce Cunningham Dance Company, noticed her drop to the ground. As he described it, while the other students were leaving the studio, Forti got down on her hands and knees to crawl on the floor, hair hanging in her face. In the context of an upright dance class, that was practically a savage act. But Paxton realized it was what she needed, and it made him curious about her. “Was she returning to basics, the roots of movement?”[xlvii] [Paxton 59]

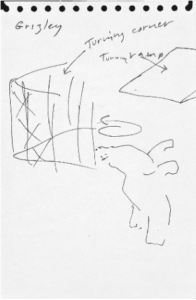

Forti’s Grizzly Turning Corner, 1968, via The Box, L.A.

Indeed she was returning to the roots of movement, which for her lay in the movement of animals. This pull toward the earth may have reminded her of the comfort she felt at the age of four watching the bears in Bern. It was a touchstone, a reminder of something basic in life. Bears don’t throw words and movement around just to be clever. She could channel a lumbering bear or a hopping frog whenever she needed to.[xlviii]

Although Forti did not cotton to the Cunningham technique, it was at the Cunningham studio that she found out about Robert Dunn’s composition class. A pianist who played for classes at the studio, Dunn had taken John Cage’s famous course in experimental music at The New School for Social Research. The course became an incubator for new modes of performance, and students included future interdisciplinary artists Allan Kaprow and George Brecht; visitors to the class included Jackson Mac Low, Jim Dine, and Yoko Ono.[xlix] Cage himself had taught a composition class at the Cunningham studio in the 1950s; by using methods of indeterminacy he rejected the theme-and-variations format that had been taught by Louis Horst, Martha Graham’s musical director. Not wanting to continue, he asked Dunn to take the reins starting in the fall of 1960.[l] Dunn had played piano for Horst’s composition classes, which he considered hopelessly old-fashioned,[li] and he accepted Cage’s challenge.

Forti was among the first five who signed up for Dunn’s class, the others being Yvonne Rainer, Steve Paxton, Marni Mahaffay, and Paulus Berensohn. Dunn combined the Bauhaus artists’ focus on the nature of materials with Cage’s embrace of the everyday in art. Cage’s idea that any sound could be music was extended to Any movement could be dance. (That idea remained theoretical for Cunningham. It was Halprin and the Judson dancers who accepted pedestrian and task movement as dance.) His assignments offered structures based on Cage’s concepts of indeterminacy, and his feedback offered curiosity rather than judgment—not unlike Halprin’s feedback. Like Cage, Dunn was influenced by Eastern thought:

From Heidegger, Sartre, Far Eastern Buddhism, and Taoism, in some personal amalgam, I had the notion in teaching of making a “clearing,” a sort of “space for nothing,” in which things could appear and grow in their own nature.[lii]

To this clearing, Forti brought the richness, curiosity, and daring of Halprin’s explorations from the West Coast. And in the cauldron of Dunn’s composition class, she clarified her interests. She was steeped in the nature-based improvisations of Halprin but embraced the rigorous structures of Cage via Dunn. “Anna Halprin’s work and Robert Dunn’s work coming together really set me on my path.”[liii]

One of Dunn’s assignments was to compose a three-minute dance and not work on it more than three minutes. Because choreographing is so time-consuming, Forti quickly realized that the only way to solve the problem was to come up with a strong idea. It was the dawning of Forti’s consciousness of herself as a conceptual artist.

Remy Charlip, at the time a dancer in the Cunningham company, after watching a session of the students’ responses to the Satie assignment (which used the composer’s number structure for Trois Gymnopédies as a score[liv]), said that he was “most impressed with Simone Forti’s solution to the assignment.”[lv]

Forti handled that assignment in a way that forced her to be physical:

I decided that being up in the air was going to be my neutral position for it. I would begin with a jump and had to land with a certain number of points of my body touching the floor. Then I would jump again, and land with a different number of points of my body touching the floor. These numbers were determined, somehow, by the phrasing in the music. It was very awkward to do and wasn’t pretty to see, which I liked.[lvi]

Her pleasure at not being “pretty” was part of her aesthetic of plainness. Forti was such a beautiful woman and luscious mover that the unadorned aesthetic suited her. Her natural sensuality and the awkwardness of such a solution played off each other to produce a beguiling kind of restraint.

But there was also a conscious component to this preference for plainness, which had to do with what she (and Rainer as well) perceived as narcissism. “One aspect of modern dance I saw around me…was a narcissism that didn’t charm me a bit,” she wrote in Oh Tongue. Looking back on her insistence on plainness, she continued, “The interest in looking at movement, just plain generic movement, everyday movement, must partly have been a response to that narcissism.”[lvii]

Later, when Forti got together with Paxton and Brown in independent improvisation sessions, they often worked on what Forti called “rule games.” Brown relished the challenge of a structure that Forti had come up with, one that was similar to the Satie assignment:

This one was awful! Start walking across, enter and exit a rectangular space, but when you crossed it you had to have only one part of your body on the floor. And when you returned you had to have two parts of your body on the floor. Three, four, five…So you end up with everything on the floor actually when you get to ten parts. So that was sort of arduous.[lviii]

Brown considered Forti to be a mentor to both Rainer and herself, especially in the area of improvisation.[lix] She pursued the idea of games that Forti had introduced. In Brown’s Rule Game 5 (1964), the performers walked within demarcated tracks and had to get lower to the ground as they approached the seventh and final aisle. When passing a fellow performer, you had to crouch lower or rise higher depending on where your track was in the room.[lx]

The game structures drew on both Dunn’s interest in chance methods and Forti’s continued passion for observing animals. She watched long enough to discern patterns in the walking of the bears, the sparring of the chimps, the diving of otters….She noticed that some animals, like children, make up games to entertain themselves. She saw bears “whipping their bodies around…sorta like kids do somersaults or twirl or swing on a swing. It’s a free ride. It feels good, it’s fun, it passes the time.”[lxi] Describing polar bears diving into a pool, she wrote, “There remains some element of fun and the practicing of skill, an impeccable measuring and matching of shape and effort…to the length of the pool.”[lxii]

Perhaps, then, it is not surprising that she would be captivated by a human being who possessed the same combination of wild fun and impeccable measuring:

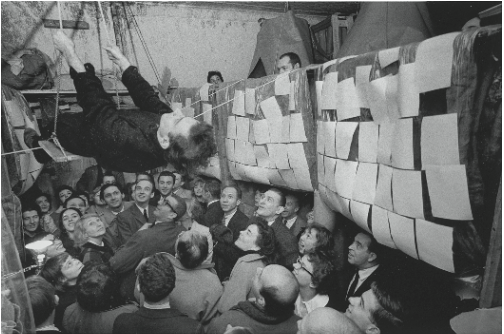

The first work I came across in New York that I felt an immediate kinship with was a piece by Bob Whitman called E.G. Part way through it, Whitman took a flying leap directly over the heads of the audience. It looked like he was going to come crashing down into the crowd when, just in the nick of time, he grabbed some bars which he had installed in the ceiling, and swung away out of sight.[lxiii]

She was attracted to the “undomesticated” (animal-like) quality of his actions.[lxiv] And she found a soul mate in Whitman (who had been a student of Kaprow). Forti started performing in his pieces and helping him paint the sets,[lxv] the first one being American Moon at the Reuben Gallery in the fall of 1960.[lxvi] Whitman brought lights, imagery, objects, fabrics, and film projections together in an ingenious and surreal jumble. The look of his works was so chaotic that sometimes they were called Happenings. But they were in no way haphazard.

Robert Whitman’s American Moon, Reuben Gallery, 1960: Lucas Samaras above, ph Robert McElroy, Getty Research Institute.

After a break-up with Morris in 1962 (long in the works), Forti married Whitman. She felt fulfilled working with him, partly because of his ability to mix media while keeping a consistent focus. She likened his theater pieces to “moving sculptures”[lxvii] “In Whitman’s work, it was going towards the central image. There was a central theme that maybe never was spelled out but poetically it was there.”[lxviii]

Some of her later works that used projections, for example Cloths (1967) and Bottom (1973), were influenced by Whitman.[lxix] Her drawings at the time were influenced by Whitman’s use of primary colors. In 1966, she made a series of vibrant “Red Hat” watercolors. “I had a big red hat,” Forti remembered, “and somehow it became the signature for this character, me, running over mountains, sometimes pursued by dark figures.”[lxx] These are striking pictures with saturated color that tread the line between the figurative and the abstract.

Watercolor series, 1966. Clockwise from upper left: Red Hat With Black Background, Red Hat Pursued With Yellow, Red Hat on Bicycle.

Defying Categories

Forti never aspired to become a dancer in the sense of the virtuosic bodies we see on a proscenium stage. She recoiled at any attempt to fit her into that mold. Taking the intensive June course in 1960 at the Martha Graham School of Contemporary Dance, she was appalled when told to hold her belly in—a standard correction in almost any dance technique class.[lxxi]

Fascinated with motion rather than dance per se, she would observe natural phenomena for hours. Over a period of days, she watched an onion grow sprouts and topple over; then she wrote a “dance report” about it consisting of two sentences that she recited in Dunn’s class. Why was this a dance? For Forti, observation, time, and change were part of dancing.

Another experience that Forti decided to view as a performance occurred when she was working at a nursery school and taking the children to Central Park:

I remember one day one of the little boys said, “You all sit there and watch me.” He had a tin can on a string, and he climbed up on this rock with it. Then he dropped it, making it bounce against the side of the big rock, almost like a puppet. We were just mesmerized watching this tin can. It made me realize that anything can be interesting. And that’s what Bob Dunn was teaching us also. I think it’s because of Bob that I could see this little event with the tin can as theater, as dance, as working with movement.[lxxii]

Forti was starting to see art in everyday experiences. She believed, as Duchamp did, that art is whatever an artist says it is. In terms of genre, she felt that you could define your own terms. Crossing disciplines was in the air in the 1960s, and she felt supported by the downtown milieu.

I have the feeling that I wasn’t the only one. I did a lot of sound pieces and I felt very free about it, calling them “dances.” I like doing one thing and calling it something else…People were doing things that really crossed lines. Lucinda Childs did a piece where she was walking over sand, leaving her footprints…Sculptors and painters were involving their own bodies…I thought of it as a broken field running… sorta like a rabbit getting across a field safely by dashing this way and then holding still, and then dashing that way so that there’s not this announcement, “I am going to make a dance” and everyone saying, “Yes, yes, it’s a dance.” It’s more like I’m going to bake a cake and then instead… [she looks around, takes an object and tosses it on the floor] There’s your cake![lxxiii]

She was aware of Duchamp’s readymades, Rauschenberg’s collages, and of course, Cage and Cunningham’s use of chance. She was right in tune with the Dada Zen sensibility that was infusing the art scene.

But something even more fundamental was going on. The blending or colliding of different forms was a way to subvert an age-old habit of Western philosophy: binary thinking. In terms of perception, this deconstruction of our tendency to polarize genres and ideas is something that La Monte Young brought into focus. During his days with Halprin, he is quoted as saying, “A person should listen to what he ordinarily just looks at, or look at things he would ordinarily just hear.”[lxxiv]

Just as Young proposed a melding of sound and sight, Forti proposed, in her own moving body, a melding of art and dance:

You are composing when you’re improvising. One of the kinds of improvising I sometimes do is to stream myself around through space. And I think it’s very close to abstract expressionism in painting. To use your body almost as a bunch of wet paint that I can move around the space. In my imagination I almost leave traces.[lxxv]

In a physical, intuitive way, she had already eluded binary thinking. During this period she continued making drawings and watercolors. She felt she was equally a maker of dance and a maker of visual art.

All these experiences of knitting different modes together led up to the moment when she sat on her bed and drew five “ideas” that she decided to call “dance constructions.”

The Dance Constructions — A Landmark in the Arts

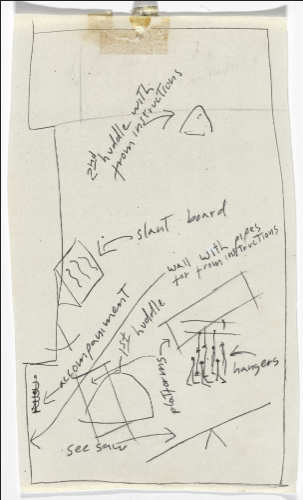

Forti’s floor plan for the Dance Constructions

In the spring of 1961, La Monte Young invited Forti to create an evening in the series of interdisciplinary programs he had organized at Yoko Ono’s loft at 112 Chambers Street.[lxxvi] Forti easily came up with ideas that merged the task elements of Halprin with an object or visual situation. She called them dance constructions, and they embodied the non-dualistic thinking that she had been working toward all along. She was still with Morris at the time, so he built the necessary objects from simple materials like wood and ropes. She presented these dance-and-sculpture hybrids in a bare studio. There were no seats and people could mill about, viewing the pieces from any orientation.

What follows is a partial list of the events included in “Dance Constructions & Some Other Things” in May of 1961. I describe most of them in the present tense because these structures exist and can be performed at any time. In fact, the Museum of Modern Art recently acquired the dance constructions—a remarkable development. Just as they would buy a tangible work of art, they have bought Forti’s dance constructions, to be loaned out and performed according to Forti’s stipulations. The acquisition, which has been in the works for several years, is considered “groundbreaking” by the curators at MoMA.[lxxvii] Not to mention that it cements Forti’s reputation as a leading figure in the avant-garde.

Slant Board consists of an 8-foot square ramp with a 45-degree incline to which several knotted ropes are attached. Three or four performers pull themselves across the surface, going under and over each other while holding a rope. The physicality of pulling on the rope as the legs grapple with the incline—a bit like rappelling in a climbing gym—ensures a certain level of difficulty.

Slant Board (1961), Forti at upper right, Stedelijk Museum,1982.

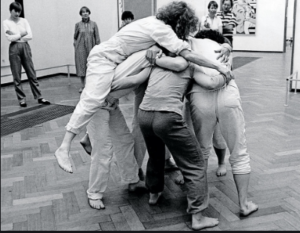

Huddle, later sometimes titled The Mountain, is a moving sculpture of humans. Six to nine people cluster together to form a group that collectively makes a small mound, girding themselves by holding one another, shoulder-to-shoulder, heads lowered. One at a time, each person extricates from the group and climbs up, over, and down the huddle of other bodies, feeling the surfaces with her or his body. The idea is to keep it plain, to focus on the simple task of climbing across the top of the “mountain.”

Forti in Huddle, Stedelijk Museum, 1982

In From Instructions (also called Instructions for a Dance), again, no concrete object, just two people and two conflicting sets of instructions. Forti told Morris to tie his sculptor friend Robert Huot to the pipes jutting from the wall, and she told Huot to lie on the floor no matter what. Not surprisingly, the piece devolved into a wrestling match.[lxxviii]

Platforms consists of two low and long, hollow platforms of slightly different dimensions. A man helps a woman crawl underneath one of the platforms, then takes his place under the other one. From that hidden position, they whistle, responding to each other’s sounds, for a designated period of time. The man then emerges from his cave and, adding a chivalrous touch, he goes to help the woman out and up.

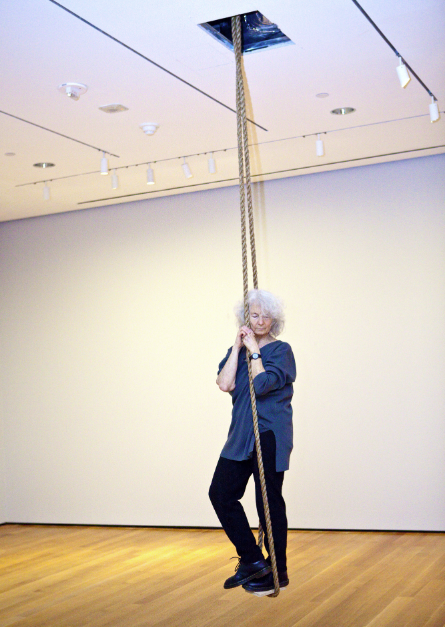

“Accompaniment for La Monte’s 2 Sounds” (1961), MoMA, 2009, ph Yi-Chun Wu

For the most enigmatic piece, Forti used a sound score recorded by Young and fellow minimalist Terry Riley the previous year at Halprin’s studio. For Accompaniment for La Monte’s “2 sounds,” and La Monte’s “2 sounds,” she steps into a hanging rope loop about one foot off the ground. An assistant winds her all the way in one direction, like kids do with a rope swing, and then lets ’er rip. Unlike kids, however, this is done to an almost unbearably harsh combination of two simultaneous sounds. Forti describes them this way: “One sound I think is a glass or a nail on a window, those are the high pitches, and the other one is a wooden mallet rubbing on a gong.”[lxxix] (The two sounds were actually called “Cans on Window” and “Drumstick on Gong.”[lxxx] This score was later used for Merce Cunningham’s notorious Winterbranch in 1964, and is described slightly differently on the Cunningham Trust’s website.[lxxxi]) As the momentum untwists her, then twists her in the other direction, she adopts a waiting, listening expression on her face. The loud scraping sounds are gloriously god-awful. Says Forti, “I’m listening to it and the audience is listening to the music, and I have some idea that I help them listen.”[lxxxii]

When I saw Forti perform this work at the Museum of Modern Art in 2009, the audience definitely needed help staying calm while being bombarded with Young’s sounds. Watching her slow down to eventual stillness was a beatific thing to witness. Her face, like an Italian Renaissance portrait, has a timeless beauty, and in its listening mode emanated a serenity that coexisted with (or, as indicated in the title, accompanied) the twelve-minute racket. We were in the presence of a poetic—and somehow spiritual—example of stillness and acceptance.

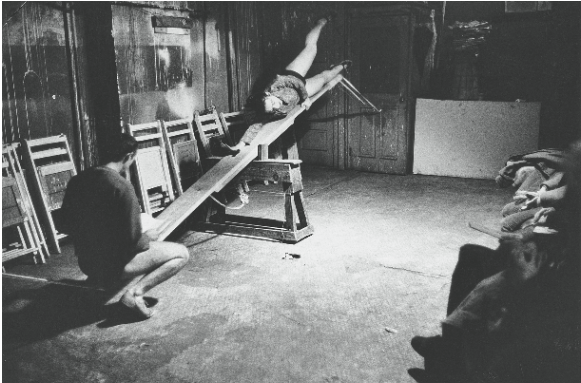

Forti now counts two earlier works as dance constructions as well: Roller Boxes (also called Rollers) and See-Saw. These two were performed in December, 1960 at the Reuben Gallery in a shared program with Jim Dine and Claes Oldenburg. See-Saw was a crude see-saw whereby two performers (Morris and Rainer in the first performance) used structured improvisation to experiment with balancing each other out. A noise-making toy emitted a “moo” each time the balance was tipped.

Roller Boxes involved a pair of wooden boxes on swiveling wheels, in which Forti and Patty (Mucha) Oldenburg sat. The idea was that they would both hold a single tone while audience members pulled the boxes by a rope.

Forti recently described what actually happened:

The audience started careening us around…When I was a kid I loved the bumper cars, and this was very much like being in the bumper cars except that they were wooden boxes.…The audience was jumping, running to stay out of the way. Our boxes were banging together, and we were screaming. We were lucky we didn’t get hurt.[lxxxiii]

In subsequent performances, Forti, concerned about safety, asked people she knew, rather than random audience members, to pull the boxes.

Impact on Judson Dance Theater

The dance constructions had a far-reaching impact. These works, and Forti’s approach in general, were a strong influence on four of the groundbreaking Judson pack: Paxton, Morris, Rainer and Brown. Paxton, who performed in Forti’s program and later became another seminal figure in postmodern dance, recognized the dance constructions as a precursor to Judson Dance Theater. He said they were like “a pebble tossed into a large, still, and complacent pond. The ripples radiated.” He wrote that the Judson choreographers “took courage from” her daring hybrids.[lxxxiv] His solo Flat (1964), in which he walked around, removed almost all his clothing one piece at a time, and hung the garments on hooks affixed to his bare skin, seems to echo the unity of body and object of the dance constructions.

But on a more philosophical plane, Paxton ruminated about the divesting of the trained body that was necessary for him to perform in the dance constructions. He sent me this in an email:

Simone demonstrated her movement for the cast. There were no pointed toes, no extremely extended limbs. It is not easy to shed these elements. First with Simone, and later in Judson performances, there was the question about movement not governed by the Western Dance Aesthetic. To that point, Simone said, “I have worked hard on my ideas, and I don’t want other people’s ideas in my work.” And evidently that meant “not the Western world’s” ideas of movement. As one of her dancers I had to honor her wish, and then to confront the system I had before training, admit one existed, try to discover the innate movement I had prior to hours every day trying to change that movement. It was self-shaking, paradoxical, and enlarging…My Modern Dance–made body needed to relax and reform. “I” needed to admit that I was also non-conscious, a more complex entity than I had imagined myself, or could imagine myself.

Simone’s work provoked what I might call a growth of awareness, and that growth seems to be in the form of inhabitable viewpoints, such as seeing an elusive former, preconscious self from the post-training vantage, imagining a post training body from the hope of a pre-training state, my conscious mind trying to discern what my non conscious mind is, etc, a cycling circling twisting attempt to catch oneself in the wild, unaffected by the fact one is watching. The cards are stacked against us, but the struggle makes us stronger, or just makes us us.[lxxxv]

Like Paxton, Morris, who went on to make several performance pieces at Judson, also felt the need to divest. But since he was not a dancer, it wasn’t dance training he was trying to get rid of. It was the disconnect between the making of a work and “the static, finished product.” His stated problem was that the object had no relation to the process that produced it.[lxxxvi] For him, sculpture that extended into time was a solution to what he considered a troubling difference. “I found in the theater a situation where that dichotomy was not the case.”[lxxxvii] (The term “theater” was Cage’s term for aNY time-based art “that engages both the eye and the ear.”[lxxxviii]) In his eyes, his ex-wife was a part of that solution. In fact, he places Forti in the line of other major figures: “A thread runs from Duchamp to Cage to Forti and is part of the larger story of modernism,” Morris wrote in 2012. “All share a common strategy.”[lxxxix] What he is referring to is that all three had broken through convention to discover that the materials one is working with can suggest a single decision that governs the artistic process.

The physical struggle between Morris and Huot triggered by From Instructions may have served as a seed for their collaborative duet War (1963) at Judson. They really went at it—wearing outlandish costumes while yelling loudly and taking whacks at each other—but only for a few seconds. War was one of the more bizarre performances at Judson. Rainer loved it; Paxton hated it.[xc]

Back on Halprin’s dance deck, in response to one of Halprin’s assignments to observe nature, Morris had chosen to focus on a rock. Forti still has a vivid memory of it:

Bob had observed a rock, and he started out lying down. Over a period of three minutes he drew himself together until he was all balled up and balanced on the smallest part of himself as possible, as that rock—which kinda foretold some of the work that he was then going to do.[xci]

Later Forti sometimes performed with the idea of placing herself as a stone in different areas of the performance space.[xcii]

When Judson Dance Theater launched on July 6, 1962, it was a natural outgrowth of the Dunn workshop that Forti was very much part of. But by that time she was involved with Whitman, who was in a different camp, so to speak. Most of her fellow students in the Dunn class—Rainer, Paxton, Brown, Lucinda Childs, Rudy Perez, Elaine Summers—performed as part of the Judson collective, which is widely known as the crucible of postmodern dance. As Sally Banes has written, that first concert “proved to be the beginning of a historic process that changed the shape of dance history.”[xciii]

Possibly the two Judson renegades most influenced by Forti were her friends Yvonne Rainer and Trisha Brown. Needless to say, they both went on to become seminal figures in postmodern dance. Rainer met Forti in New York in 1960 through fellow Bay Area dancer Nancy Meehan.[xciv] That fall, after the Halprin intensive, Rainer was sharing a studio with Forti and Morris in lower Manhattan:

Around this time I saw Simone do an improvisation in our studio that affected me deeply. She scattered bits and pieces of rags and wood around the floor, landscape-like. Then she simply sat in one place for a while, occasionally changed her position or moved to another place. I don’t know what her intent was, but for me what she did brought the god-like image of the dancer down to human scale more effectively than anything I had seen. It was a beautiful alternative to the heroic posturing that I felt continued to dominate my dance training.[xcv]

See-Saw (1960), with Yvonne Rainer above and Robert Morris below, ph Robert McElroy

Forti’s effect on Rainer is even more strongly expressed in this excerpt from Rainer’s diary of September 1961: “I am indebted to Simone for my awakening as a dancer. I can say that my creative life as a dancer began when I met her, shortly before our trip west last year.”[xcvi]

Another artistic revelation for Rainer was working on See-Saw. About that experience, Rainer says of Forti, “She made no effort to connect the events thematically in any way…And one thing followed another….Whenever I am in doubt I think of that. One thing follows another.”[xcvii]

This disjunctiveness—one thing following another even though it may not make obvious thematic sense—is typical of the way Forti works. Perhaps it owes something to the Dada Zen sensibility of Cage as well as to the Halprin tendency to “flip” meaning. Forti had an uncanny ability to commit to each thing as it happened—even when there was no continuity. “My style is more to jump from things to things,” she said. “If I stay with something and see where it evolves to, I’d feel a little bit imprisoned by it. I get a little claustrophobic.”[xcviii]

Forti’s association with Trisha Brown, whom she met that same summer of 1960 at Halprin’s course, continued throughout the Judson years and beyond. Brown was immediately struck by Forti’s inventiveness at the house of Halprin. For years she retained a vivid image of Simone “with a garden hose pointed at her mouth, singing a beautiful Italian aria. It was riveting. I didn’t know what category of behavior that went into.”[xcix]

That happy confusion of categories, of course, became even more pronounced in the dance constructions. One can see their influence on Brown’s equipment pieces. For example, Brown’s Planes (1968) took the incline of Slant Board and made it so steep as to be an almost vertical plane with holes to get one’s feet into—a precursor of the more famous Walking on the Wall (1971).

Trisha Brown’s Lightfall, with Brown and Steve Paxton, sound by Forti, ph Al Giese, 1963.

Forti and Brown shared a sensibility that favored a relaxed body and the freedom to go wild while improvising. They trusted each other artistically, and Forti provided sound for several of Brown’s pieces. When Brown performed her first solo, Trillium (1962), at Maidman Playhouse[c] and later at Judson, the sound score was a recording of a vacuum cleaner with Forti vocalizing tones she heard in the sound of the machine.[ci] And for Brown’s Lightfall (1963) at Judson’s Concert No. 4, Brown and Paxton performed the perching-and-falling duet to a recording of Forti whistling.[cii]

Rainer, Paxton, and Brown were stalwarts in the Judson rebellion who each went on to become a force in contemporary dance (in Rainer’s case, film as well). In recognizing Forti’s influence on them, we recognize her influence on the whole phenomenon of postmodern dance.

An Emotional Pull

While many of the male minimalists explained their motivation with mathematical formulas or academic theories, some female artists gave an emotional motivation. For example, Morris has written, “[T]he decision to employ objects came out of considerations of specific problems involving space and time.”[ciii] In Forti’s writing, we see the words “want” and “feel” and “need.” Even her reaction to Cage’s ideas was emotional. Although she threw herself into solving Dunn’s assignments that were based on Cage’s chance methods, what stayed with her was learning about Cage’s own expressed need”

[Robert Dunn] said that John had wanted to be able to hear sound, and that when he listened to music that was in any way traditional, he’d know that after this sound and that sound and that sound, then there could be this or that or that, but it was gonna be one of them.…he always had a double experience of the sound itself and the expectation. And he wanted to be able to just hear sound without any expectation…I felt from that, that if you need something, you can create a structure that will give it to you.[civ]

Ultimately Cage, via Dunn, had given Forti permission to set up whatever framework she needed to satisfy her emotional/artistic needs. And what she needed at that time was physical contact. Ultimately, that need, plus her growing interest in mixing genres, fueled her dance constructions:

I had just left San Francisco, I had just left the trees, I had just left the mountains. I needed to climb, I needed to feel my physical strength.…And it occurred to me that I could make this little mountain, which I call the Huddle… and be part of that structure or climb on it, that I could make something that could give me what I was needing.[cv]

Floating in Water, 1971, via The Box, L.A.

In another interview, while talking about her move to New York, she admits to a level of vulnerability rarely acknowledged by artists, male or female:

I think it hit me especially hard because the marriage [to Robert Morris] wasn’t going so well. I remember feeling that the nature that I’m really part of, that I can really still experience, is my weight—that I take up space and have weight…The work was a way for me to connect to universe. To say, I’m here, I feel confused, bad, and lost, but I’m still attached to the earth.”[cvi]

Forti’s emotional radar was alerted over an ethical issue in 1968 when she was living and working in Rome. She tells this story about Fabio Sargentini’s Rome Festival of Music, Dance, Explosion and Flight, which she had enthusiastically helped to organize. She was horrified by a series of “experimental” explosions engineered by American sculptor David Bradshaw. In fragmentary writing that reflects her state of mind (she was known to sometimes partake of marijuana and acid in the late 1960s), she recounts the incident:

The jolt. The water rising…The fish were coming up dead…I walked over to David Bradshaw and asked him if, in the light of the dying fish, he felt one explosion had been enough. He said…that the death of the fish was not the intention of the piece, and that he would continue. Right. I just squatted beside a tree, my head in my hands. Another jolt, water rising… It is true. I was stoned and I was watching the ants at my feet. They were going crazy. Through their frenetic scrambling I had a vision of their ancient tunnels crumbling. My tears fell among them. And I was miles into the sky. And these tiny forms were people down below, scrambling on the surface of their crumbling survival structure. Radial victims of a linear intent. It is true. I was stoned. I was there, but I was not in Rome. I was with the ants.[cvii]

Forti with her father, Mario Forti, in Florence, c. 1948, via The Box, L. A.

The trauma of that experience left her feeling like the New York art world, of which Bradshaw was a part, was becoming as hawkish as U.S. foreign policy in its disregard for human life.[cviii] This disaffection harks back to the McCarthy era of the 1950s, when Forti felt a sense of protest, but it was more emotional than actively political.

I started going to hootenannies. Getting together with people to sing folk songs and songs of resistance. The feeling state which I picked up from that community was good for me, as was the singing. Opening my throat and singing my heart out.[cix]

A later decision, one that ignited her series of “news animations,” hinged on her feelings about the death of her father, Mario Forti.

My father died in 1983. He was an avid reader of newspapers. I’ve thought that that’s how he knew, before so many others did, that it was time to get out of Europe. When he died I figured I’d better start reading the news. Also, it felt like a way to be close to him. Still does.[cx]

Going back to her early childhood, there may be a residue from the traumatic events of her family’s escape from Europe. Although Forti has never said this, I think there is something about her work—the hunger for touch, the desire to feel the earth under her feet, the distrust of authority—that may be the legacy of being a four-year-old child bewildered by the haste with which her family had to flee their home country.

Traditions Nevertheless

Although she has railed against the conventions of the dance world, Forti also had a respect for lineage in both dance and visual art:

I felt aware that I was in the same tradition with Kurt Schwitters and I felt the tradition wasn’t gonna end with us. The continuance of this tradition like working with Ann Halprin: she also had worked with Margaret H’Doubler, who worked with exploring movement anatomically. Laban had been working with movement, even factory movement, how to lift—how to build machines so the body functions in harmony with them…When a tradition’s been going a period of time, you don’t imagine it’s gonna end with you. You’re gonna have something to do with its going on.[cxi]

She also feels in line with the tradition of another California girl—Isadora Duncan. She calls Duncan “one of the founders and sources of dance improvisation in America”[cxii] and admires how, in the Cagean sense, Duncan created a structure for what she needed.

[Duncan] who stood silently still in the center of her studio waiting for a movement impulse, was working with this very particular problem she had given herself, of clearing the environment and listening for an inner impulse.[cxiii]

Perhaps Forti’s sense of valuing the past was most poignantly expressed in a hand-written letter she wrote to Trisha Brown after seeing her perform Accumulation in Rome in 1972. She wrote that Brown’s solo, in which she returned to the first gesture (extending the thumb outward almost like a hitchhiker would) after each new movement was added, served as a kind of guide for Forti. “I used to stretch both hands to the future,” she continued. “Now I’ve been stretching one hand to the future and one to the past, and my house seems to be building up a lot stronger.”[cxiv]

Forti’s Planet, P. S. 1, 1976

Another way she connected with the past has more of a cultural basis: “In Naples people speak with their dead as much as with their saints. Enlist their help. As a Florentine Jew, I too speak with my dead. I love them, and they help me clear my mind.”[cxv]

She found reinforcement for this kind of communication in the I Ching, the ancient Chinese Book of Changes, which is the tome Cage relied on as a guide to chance procedures. This kind of connection with the past has a spiritual element:

In the I Ching they often talk about music and dancing and inviting the ancestors to be present…I do have a sense of the ancestors …being present in this ongoing, redoing and redoing…as our way of making art changes. It is a way of having the antenna to intuitions that are vital to survival as one of its functions. I see myself as a worker in the ongoing format of divination.[cxvi]

Legacy, True and False

Big Room, 1974. ph Robert Alexander, via Fales Special Collections at NYU, and The Box, L.A.

In the years following the dance constructions, Forti has gotten involved in many new and recurring collaborations. Her work with composer Charlemagne Palestine, which began when they met at California Institute of the Arts in 1970, led to the “Illuminations” series, including various ways of performing circles (she was “banking from orbit to orbit”[cxvii]). Her animal studies in the 1970s and 1980s were performed with musician Peter Van Riper. The news animations, ongoing since the 1980s, braid words and movement together in a slyly oblique way. In the late 1980s Forti started feeling that integrating one’s body and mind was not enough. She wanted her art to be aware of the world too. Thus she came up with a way of framing her work that she called “Body, Mind, World.”[cxviii]

Forti has continued to perform in museums, galleries, and festivals in the United States and Europe. A part-time faculty at UCLA from 1997 to 2014, she has given workshops all over the world (except Germany, where she has refused to go[cxix]). About her approach to teaching, she says, “I still teach the workshop process that I learned from Anna.”[cxx]

Her practice of improvisation, now often combining dance and words, is part of her legacy. She aims not only to cross the barrier from dance to art, but from body to mind:

Movement, or improvisation, always involves following impulses while also watching the whole situation…There is always thinking going on while the movement is happening…What I want to impart… is the experience of having the motor centers and the verbal centers of your mind communicating with one another, working together. I want to facilitate that dialogue.”[cxxi]

Forti’s drawings and watercolors have been shown at galleries in Los Angeles, New York, and Zurich. The holographic pieces she made with holography pioneer Lloyd Cross in the ’70s (Striding Crawling and Angel) are in the permanent collections of the Whitney Museum of American Art and the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam. Forti, who has received several lifetime achievement awards,[cxxii] was the subject of a major retrospective the Museum der Moderne in Salzburg, Austria, in 2014. As mentioned, she has a permanent relationship with MoMA, which has acquired the Illumination ink drawings that came out of her work with Palestine, as well as her dance constructions, giving her the status of a major visual artist.

Illustrious dance artists who have been influenced by Forti, including Susan Rethorst, David Zambrano, Daniel Lepkoff, and K. J. Holmes, have made her sensibility visible to a new generation of dancers. Her legacy is inextricably entwined with her longevity, allowing several generations to experience her work. Recently Forti reunited with Charlemagne Palestine for a reprisal of their “Illuminations” series. When this was performed at MoMA in 2014, Brian Seibert of The New York Times described her presence as Palestine hummed and made sounds with a glass and a laptop:

Meanwhile, Ms. Forti, in black pants and a white sweater, eyes closed, slowly rolled across the floor. The beauty of her approach, if also its limitations and risks, lies in how she doesn’t put on a show; she just is. At one point, she directed attention to the moon outside by saying “moon.”[cxxiii]

Clearly, she still revels in her aesthetic of plainness and her connection to nature.

But there is also a part of her legacy that has gone beyond actual witnessing to rumor and hearsay. You know that an artist’s reputation has reached the realm of legend when that happens. In the fall of 2014, I attended a performance event in a small loft in SoHo. All of us were standing, packed like vertical sardines, shoulder-to-shoulder, ear-to-ear. I could not help but overhear one young Italian man telling his friends this story with great authority:

When Simone Forti’s relationship with Robert Whitman broke up, she was so unhappy that she had to do something very different. She went to Rome and she did a piece where she got naked and performed in a cage with a bear. A big f—-g bear!

I was impressed. But after a moment I realized there was a chance this story might not be entirely true. So I e-mailed Simone and asked her about it. I received a reply right away.

Hi Wendy,

Well, I really should leave that rumor intact. But as I remember things, I did go to Italy shortly after breaking up with Whitman, and began my zoo studies. Then, years later, I was in Paris to perform with Charlemagne. While walking in the street on a cold day, with a videographer associated with the Sonnabend Gallery, I saw a cage-like mid basement walk-down to an entrance. I don’t know how else to describe it. We decided to shoot me moving down in that pit-like place. After a while of doing my bear studies movement, I took off my clothes, leather jacket and all, and continued naked. There’s a very nice video of that, which was once shown in a mini retrospective of mine at MoMA.

With love from Paris where I just performed with Charlemagne, fully dressed,

Simone

One of Forti’s News Animations, ph Ellen Crane, 2017, via Radical Bodies

[I originally wrote this essay for the exhibit I co-curated titled “Radical Bodies: Anna Halprin Simone Forti, and Yvonne Rainer in California and New York, 1955–1972.” It originated at the Art, Design & Architecture Museum, UC Santa Barbara in 2017, and came to the NY Public Library for the Performing Arts. The Radical Bodies exhibition catalog was published by UC Press. Special thanks to The Box L.A. for this posting.]

¶¶¶

Endnotes

[i] Forti, Simone, “Reflections on the Early Days,” Movement Research Performance Journal #14, Spring 1997 (a special edition titled “The Legacy of Robert Ellis Dunn”), 4.

[ii] Simone Forti, Handbook in Motion (1974), (Northampton: Contact Editions, 1997), 129

[iii] Simone Forti, “Full Moves: Thoughts on Dance Behaviors,” Contact Quarterly 9, no. 3 Fall 1984, 8.

[iv] E-mail to the author, October 17, 2015.

[v] In an email to the author January 8, 2016, Forti elaborates: “Here is the narrative I’ve settled on: We crossed the border into Switzerland in December of 1938. There had been Kristallnacht and the way across the border was easy at that moment because many Italians were heading to Switzerland for their ski holidays. The story goes that we put our skis on top of the car and were waved through along with everyone else. Why did we hide our departure? Was Fascist Italy already blocking Jews from leaving? Supposedly, no more passports were being issued to Jews and ours were about to expire.”

[vi] Oral History transcript of Simone Forti, interviewed and recorded by Louise Sunshine, May 8, 1994, Dance Division, NY Public Library of the Performing Arts, 1–3.

[vii] Ibid., 7.

[viii] Forti, “Full Moves,” 7.

[ix] Oral History transcript, 8.

[x] Conversation with the author, June 10, 2014.

[xi] Bennington College Judson Project (1981) dir. Wendy Perron, video interview with Simone Forti conducted by Meg Cottam, in Forti’s Manhattan studio.

[xii] Forti, Oh Tongue (Los Angeles: Beyond Baroque Books, 2003), 125.

[xiii] Oral History transcript, 10.

[xiv] E-mail to the author, Sept. 21, 2015.

[xv] Forti, Handbook in Motion, 32.

[xvi] Ibid.

[xvii] Forti, Oh Tongue,131.

[xviii] Ibid., 132.

[xix] Conversation with the author, June 10, 2014.

[xx] Breitwieser, Sabine, “The Workshop Process, In Conversation with Simone Forti,” in Breitwieser, ed. Simone Forti: Thinking with the Body, (Salzburg: Museum der Moderne, 2014), 21. Exh. catalog

[xxi] Conversation with the author, June 10, 2014.

[xxii] Author’s phone conversation with June Ekman, September 7, 2015.

[xxiii] Ibid.

[xxiv] Forti, Oh Tongue, 132.

[xxv] Breitwieser, 21.

[xxvi] Oral History transcript, 24

[xxvii] Breitwieser, 22–23. Note: Shunryu Suzuki, author of the influential book Zen Mind, Beginner’s Mind, founded the San Francisco Zen Center in 1962.

[xxviii] Ross, Janice, Anna Halprin: Experience As Dance (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2007), 80.

[xxix] Kay Larson, Where the Heart Beats: John Cage, Zen Buddhism, and the Inner Life of Artists (New York: Penguin Books, 2012), 79.

[xxx] Cage, John, Silence: Lectures and Writings by John Cage (Middletown: Wesleyan University Press 1961, paperback 1973), xi.

[xxxi] Bennington College Judson Project.

[xxxii] Cypis, Dorit, “Between Conceptual and Vibrational,” X-tra, Vol 6 No. 4, Summer 2004, 10.

[xxxiii] Oral History transcript, 25.

[xxxiv] Ross, 151.

[xxxv] Ibid.

[xxxvi] Forti, Oh Tongue, 117, and Cypis, 10.

[xxxvii] Bennington College Judson Project.

[xxxviii] Oral History transcript, 32.

[xxxix] Forti, Handbook in Motion, 53.

[xl] Author’s phone conversation with Forti, October 19, 2015.

[xli] Author’s phone conversation with Forti, August 25, 2015.

[xlii] Steffen, Patrick (2012), “Forti on All Fours,” Contact Quarterly Online Journal, https://community.contactquarterly.com/journal/view/onallfours.

[xliii] Gerard Forde has exposed a discrepancy as to when the couple moved east. Forti had said 1959, but Morris dates the relocation as 1960. Forti has told me that Morris has the more dependable memory. Forde, Gerard. “Plus or Minus 1961—A Chronology 1959–1963.” online

[xliv] Ross, 136.

[xlv] Oral History transcript, 22.

[xlvi] Forti, Handbook in Motion, 34.

[xlvii] Paxton, Steve, “The Emergence of Simone Forti,” Simone Forti: Thinking with the Body, 59.

[xlviii] See Forti, Oh Tongue, 135, for Forti’s eloquent description of the “dancers among the captives in the zoo.” She describes, among other actions, “bears running back and forth up a ramp and …reaching and spiraling their noses skyward…the biggest male of a herd of deer doing a terrifying leap straight at but just short of at the newborn fawn.”

[xlix] Banes, Sally, Greenwich Village 1963 (Durham and London: Duke University Press, 1993), 28, and Biesenbach, Klaus and Cherix, Christophe, Yoko Ono: One Woman Show 1960-1971, New York: MoMA, 2015).

[l] Charlip, Remy, Movement Research Performance Journal #14, Spring 1997, 10. Charlip was a dancer, choreographer, costume designer, and writer and illustrator of children’s books.

[li] Soares, Janet Mansfield, Martha Hill and the Making of American Dance (Middletown: Wesleyan University Press, 2009), 250.

[lii] Dunn, Robert, Movement Research Performance Journal #14, 1997, 1, originally printed in Contact Quarterly, Winter 1989.

[liii] Forti, Simone, video interview in Judson Dance Theater: 50th Anniversary internet series, Artforum.com, 2012.

[liv] Banes, Sally, Democracy’s Body: Judson Dance Theater 1962–1964 (Ann Arbor: UMI Research Press, 1983) (Durham: Duke University Press, 1993), 4.

[lv] Charlip, Movement Research Performance Journal #14, 10.

[lvi] Breitwieser, 24.

[lvii] Forti, Oh Tongue, 117.

[lviii] Brown, Trisha (2004) Trisha Brown: Early Works 1966–1979, DVD Two: A Conversation with Trisha Brown and Klaus Kertess, ArtPix DVD.

[lix] Ibid.

[lx] Teicher, Hendel, Trisha Brown: Dance and Art in Dialogue: 1961–2001 (Addison Gallery, distr. Cambridge: MIT Press, 2003), 300.

[lxi] Author’s phone conversation with Forti, August 25, 2015.

[lxii] Forti, “Full Moves,” 7.

[lxiii] Forti, Handbook in Motion, 35.

[lxiv] Forti, Simone (1999), “Animate Dancing: A Practice in Dance Improvisation,” in A. Cooper Albright, & D. Gere (Eds), Taken By Surprise (Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press, 2003), 61.

[lxv] Kaminski, Astrid, “Join the Movement,” Frieze.com, Issue 168, January-February 2015, http://www.frieze.com/issue/article/join-the-movement/.

[lxvi] Forde, Gerard

[lxvii] Cypis, 10.

[lxviii] Oral History transcript, 51.

[lxix] Breitwieser, 24.

[lxx] Ibid., 30.

[lxxi] Forti, Handbook in Motion, 34.

[lxxii] Breitwieser, 65.

[lxxiii] Bennington College Judson Project.

[lxxiv] Ross, 145.

[lxxv] Oral History transcript, 67.

[lxxvi] Although most researchers say that Young organized the series at Yoko Ono’s loft, Ono has expressed her feeling that they organized it together. See “A Letter to George Maciunas,” 1971 and subsequent note in 2014, both appeared in Biesenbach, 70-71

[lxxvii] Phone conversation with Ana Janevski, associate curator, Department of Media and Performance Art, Museum of Modern Art, January 20, 2016.

[lxxviii] Oral History transcript, 45.

[lxxix] “In Conversation: Simone Forti with Claudia La Rocco,” Brooklyn Rail, April 2, 2010

[lxxx] Janice Ross, “Atomizing Cause and Effect: Ann Halprin’s 1960s Summer Dance Workshop,” Art Journal, Vol. 68 No. 2, Summer 2009, 75.

[lxxxi] In the Dance Capsules section of the Cunningham Trust website, David Vaughan writes that La Monte Young’s 2 Sounds consisted of “the sound of ashtrays scraped against a mirror, and the other, that of pieces of wood rubbed against a Chinese gong.” http://dancecapsules.mercecunningham.org/overview.cfm?capid=46113

[lxxxii] Ibid.

[lxxxiii] Taken from unused footage of an interview with Simone Forti conducted for Feelings Are Facts: The Life of Yvonne Rainer, the film by Jack Walsh.

[lxxxiv] Paxton, 61.

[lxxxv] Email to the author, August 27, 2015.

[lxxxvi] Weiss, Jeffrey with Davies, Clare, Robert Morris: Object Sculpture: 1960–1965 (New Haven and London: Yale University Press in association with Castelli Gallery, 2013), 300.

[lxxxvii] Ibid., 33.

[lxxxviii] Kirby, Michael, and Schechner, Richard, “An Interview with John Cage,” Tulane Drama Review, Vol. 10, No. 2 (Winter, 1965), 50.

[lxxxix] Morris, Robert, “A Judson P.S.,” Judson at 50, Artforum.com.

[xc] See Rainer’s description of War in Banes Democracy’s Body, 101, and Morris’ explanation of War in “Judson Dance Theater: 50th Anniversary,” Artforum.com, June 8, 2012, http://www.artforum.com/words/id=31187

[xci] Walsh, Jack.

[xcii] Ibid., 69.

[xciii] Banes, Democracy’s Body.

[xciv] Meehan went on to become a great dancer with the Erick Hawkins.

[xcv] Rainer, Yvonne, Feelings Are Facts, Cambridge: MIT Press, 2006), 195–6.

[xcvi] Ibid., 217.

[xcvii] Rainer, Yvonne, Avalanche 5, Summer 1972, page?.

[xcviii] Oral History transcript, 68

[xcix] Brown, Trisha, Trisha Brown: Early Works 1966–1979, ArtPix Videos.

[c] Forde, 23.

[ci] E-mail to the author, September 21, 2015.

[cii] Forde, 41.

[ciii] Morris, Robert, “Notes on Dance,” Tulane Drama Review, Vol. 10, No. 2, Winter, 1965 © The MIT Press, 180.

[civ] Forti, Simone, video interview, Artforum.com, “Judson Dance Theater: 50th Anniversary,” August 2012 http://artforum.com/video/id=36989&mode=large

[cv] Ibid.

[cvi] Breitwieser, 27–28.

[cvii] Forti, Handbook in Motion, 100.

[cviii] Ibid., 103, and author phone conversation with Forti, August 15, 2015.

[cix] Forti, Oh Tongue, 125.

[cx] E-mail to the author, September 23, 2015.

[cxi] Bennington College Judson Project.

[cxii] Forti, Oh Tongue, 133.

[cxiii] Forti, “Animate Dancing,” 54–55.

[cxiv] Forti, Letter to Trisha Brown (1972) reprinted in Trisha Brown’s Notebooks, ed. Susan Rosenberg, October Vol. 140, Spring 2012 (MIT).

[cxv] Forti, Oh Tongue, 13.

[cxvi] Bennington College Judson Project.

[cxvii] Breitwieser, 201.

[cxviii] Forti, Oh Tongue, 113 and 122.

[cxix] Ibid., 116.

[cxx] Goldstein, Jennie, (2014), “Simone Forti in Conversation with Jennie Goldstein,” Critical Correspondence blog, posted July 10, 2014, interview June 2, 2014.

[cxxi] Breitwieser, 34–35.

[cxxii] Forti’s lifetime achievement awards include a Bessie (New York Dance and Performance Award) in 1995, a Lester Horton Award in Los Angeles in 2003, and a Yoko Ono Lennon Award for Courage in the Arts in 2011.

[cxxiii] Seibert, Brian, “Italian Touch, With a Taste of Cognac,” The New York Times, April 16, 2014, C3.

Historical Essays Uncategorized 4

[I wrote this article for the August, 2000 issue of Dance Magazine. Reprinted with permission.]

[I wrote this article for the August, 2000 issue of Dance Magazine. Reprinted with permission.]

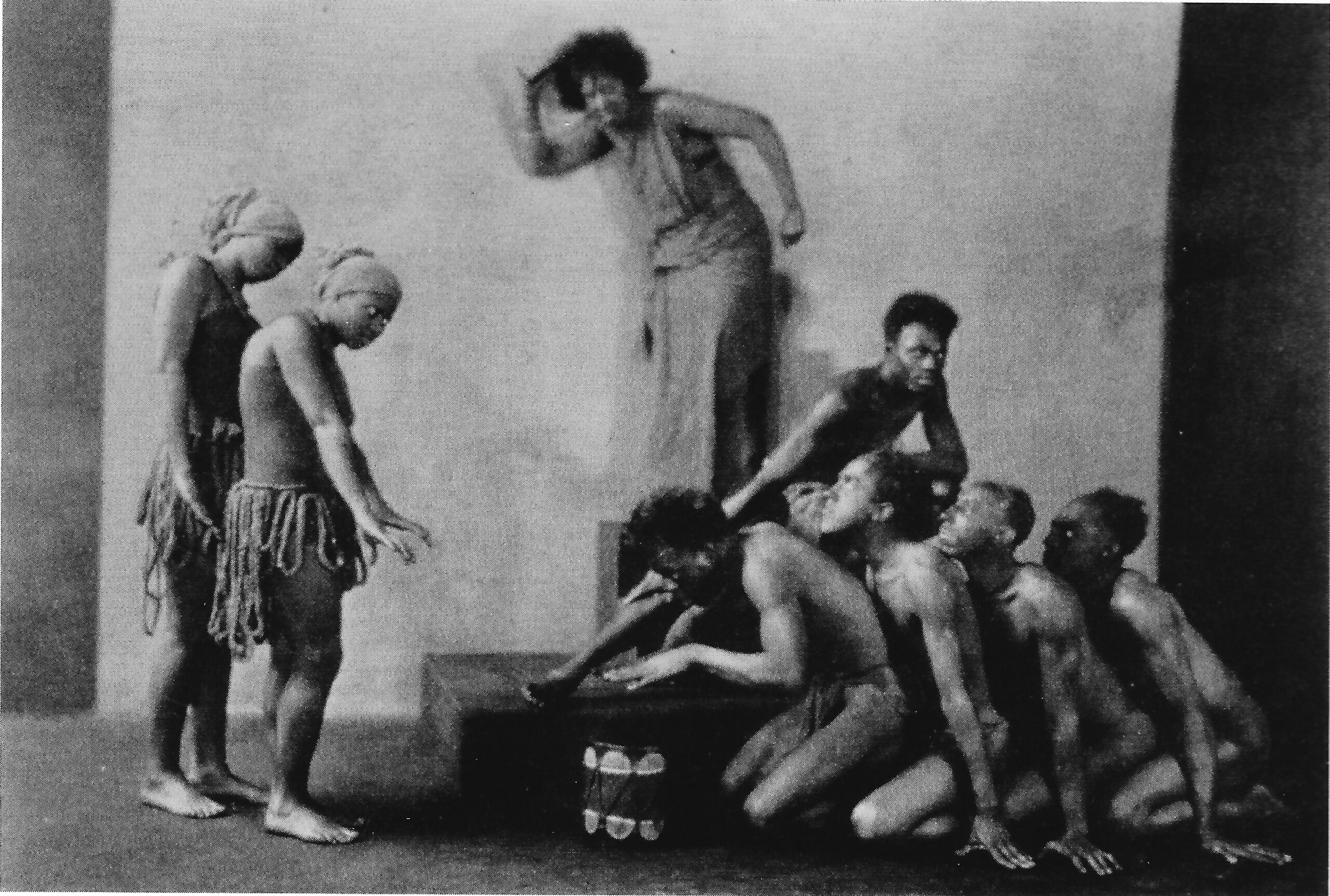

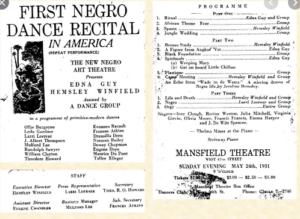

With this new/old name, the company gave the “First Negro Dance Recital in America,” presented by Winfield and

With this new/old name, the company gave the “First Negro Dance Recital in America,” presented by Winfield and