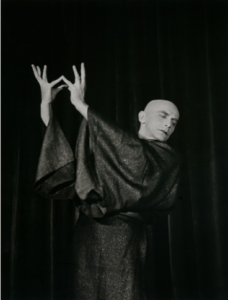

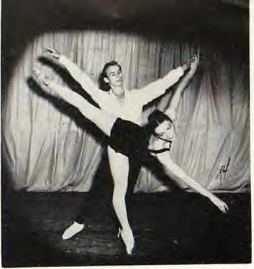

Gloria in Les Sylphides, Havana, 1937

Born Gloria González Negreira in Havana, Gloria Fokine (1925–2012) studied ballet in the same school as Alicia Alonso and her sister Cuca Martínez. She saw — and remembered — a remarkable swath of dance history. This included the beginnings of Ballet Nacional de Cuba as well as the Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo and other companies touring there in the 1930s and ’40s. In 1949 she married Leon Fokine, who was teaching classic Russian technique in Havana. They came to the U.S. and taught in Washington, DC for years, and then taught in the early years of Robert Joffrey’s company as well as at the Harkness Ballet. She taught for her sister-in-law, Irine Fokine in Ridgewood, NJ (where I took her classes as a teenager). After Leon died, she had her own school in Brooklyn Heights from 1978–84. She eventually brought her knowledge of ballet to her position as the photo editor for Dance Magazine. For a complete obit click here.

I interviewed Gloria on September 1, 2004, and it was printed in Ballet Review in the Spring 2007 issue.

(WP) Wendy Perron

(GF) Gloria Fokine

WP: What are your earliest memories of seeing dance?

GF: In Cuba there was an organization called Sociedad Pro-Arte Musical, which was formed by some socially prominent ladies for the purpose of bringing culture to Cuba. They built a theater and they proceeded to bring the best concert artists. There I saw [Sergei] Rachmaninoff, [Valdimir] Horowitz, [Yehudi] Menuhin. There was a Russian immigrant, Nicolas Yavorsky, who had studied dance, and when he left Russia during the revolution he joined a Russian opera as a dancer and wound up in Cuba. So the Pro-Arte ladies thought, “Aha, good opportunity,” and they opened the ballet school. In the beginning they had the classes on the stage, but they built a very nice studio in the top of the theater. Yavorsky, who was a person of exquisite taste, decided to do, for his first production, Sleeping Beauty. It was lavish. I was six years old, and my mother took me to see the performance — my first ballet performance. I remember a little girl as the Bluebird who had a little suit, blue, with lots of jewels in the wings and jumping all the way around the stage, a dark-haired little girl. That was Alicia Alonso. She was Alicia Martínez Del Hoyo at that time, and only 11. I liked it very much. And then when I was 9 years of age my mother took me again to Pro-Arte Musical to see Coppélia, again with a little bit more grown-up Alicia Martínez Del Hoyo. The performances there were not like recitals here. Costumes were very professional; scenery was lavish.

Alicia Alonso in Coppélia

WP: And the audience was not just the parents?

GF: Oh, no, no, no, because there were the members. Pro-Arte Musical was by membership. And it was very affordable, with $3 orchestra, $2 first balcony, $1 second balcony. (Before Castro, dollars and pesos were equal.) That gave you the right to two concerts a month plus ballet, drama, or music lessons. It was a terrific organization, founded by women and run by women!

WP: Did Alicia play Swanilda?

GF: Of course, and her future brother-in-law, Alberto Alonso, was Franz. And that was it for me. I started classes in that summer, 1935, and I loved it. Yavorsky had produced two professional dancers — Alberto Alonso and Delfina Perez Gurri — and he had gone to Europe to take them to Colonel de Basil’s Company, the Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo.

Baronova and Paul Petroff in Aurora’s Wedding*

WP: Was there already a connection between the Cubans and the Russians?

GF: Yavorsky was a White Russian. He had run away from the Soviets. In 1936 Pro-Arte Musical brought the Basil company when it was full with Massine, Toumanova, Danilova, Baronova, Riabouchinska. I went to see the performance in May, and it was so hot—of course there is no air conditioning—and you were perspiring and perspiring. But when the overture starts, you don’t feel the heat. And I saw some very fabulous performances: Aurora’s Wedding with Baronova, Three-Cornered Hat with Massine and Toumanova, [the dances from] Prince Igor with Yurek Shabelevsky. And also Les Sylphides with Danilova and Toumanova and Riabouchinska, who was the most ethereal dancer — in person she doesn’t look ethereal at all. How she can transform herself into a will-o-the-wisp, like a feather — it was unbelievable.

Toumanova and Massine in Three Cornered Hat

WP: And what about Toumanova? What was she like?

GF: I was not tremendously impressed with her in Sylphides. Baronova in Aurora’s Wedding was the personification of the princess: beautiful, gorgeous, but with a strong, solid technique. I saw Toumanova with Massine in his Three-Cornered Hat and she was very beautiful. But then I saw Massine’s Présages, my first symphonic ballet.

WP: Did they had live music?

GF: Oh, yes. And the conductor was Antal Dorati.

WP: And what was your impression of Présages?

GF: I loved it. And then they did Massine’s Beau Danube, danced by Massine. He was the kind of person that he walks on the stage and fills it. He was not a classical dancer; he was more a character dancer, but he was a tremendous personality.

But there was Danilova, my dear. That little can-can she does as the Street Dancer with the very frothy skirt of deep red velvet, lined with white lace ruffles — I memorized the steps, I don’t know how. When Danilova was on the stage you never looked at anybody else. She was unique, unforgettable. Then there’s the romance between the Massine character and the Riabouchinska character, who’s a young girl, and then the Street Dancer tries to come between them. It was a thrilling experience.

In 1937 Yavorsky did Swan Lake with Alicia, and that was her last ballet with Pro-Arte as a student. She had some coaching from Baronova, who was a close friend of Yavorsky. And I made my debut in it when I was 11 or 12. I was a little buffoon, one of six kids (at right). It was Yavorsky’s choreography for the school, it was not the Petipa. We came out all in a line and then jumped.

WP: What other dancers did Pro-Arte bring?

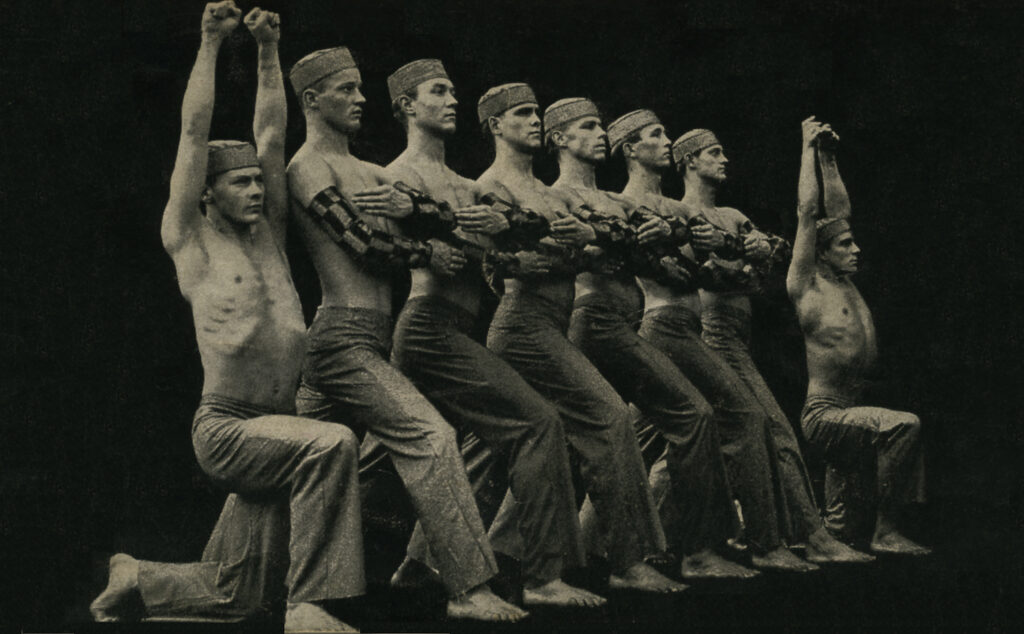

Harald Kreutzberg, 1949

GF: Harald Kreutzberg. That was my first sight of modern dance. The stage was dark and this man, head shaved à la Yul Brynner, long before Yul Brynner, with a big spotlight, controlled the stage in a manner that nobody else does. Then Pro-Arte brought Lincoln Kirstein’s Ballet Caravan, which was again a different kind of ballet. What I liked the best was Filling Station, choreographed by Lew Christensen, which he danced. And the novelty was that his costume was made of transparent plastic.

Lew Christensen in his Filling Station (1937), ph George Platt Lynes

WP: That’s very early for plastic.

GF: Yes, this was in 1938. It was very American. It was not about fairies or princesses, but about everyday situations. There was a filling station and a father and mother and the kids.

WP: Were you in other Yavorsky productions?

GF: Yes, he staged a fantastic ballet for the younger ones — The Four Seasons. He had an ability to get the most from each student. He used to yell a lot, but we adored him. “Spring” was in the woods, and the younger ones were flowers. The older ones were butterflies, fireflies. And I was Little Red Riding Hood, and she has an encounter with Peter Pan. “Summer” was a wedding in Eastern Europe and we were peasants. That was my first taste of character dance because I was the groom and had to do all kinds of pas de chat, landing in grand plié. It was very elaborate with beautiful costumes. And then “Fall” was in the castle in Scotland, with hunters. I was one of four Scotsmen, which was fun because we were taught an authentic Scottish dance by one of the older students. I had a bagpipe and a kilt. And then for “Winter” there’s the snowflakes and the wind. The younger ones were Tyrolians; I was an ice skater.

WP: What other modern dance did you see?

Ted Shawn in Mevlevi Dervish, Jacob’s Pillow Archives

GF: Ted Shawn arrived in Cuba for a Pro-Arte production. I was already pre-teen, and all I can say is “Wow.” His men were so good-looking. They did one of those pieces that imitate machinery. [You can see a 1938 film of that piece, Mechanized Labor, here.] It was wonderful. What he did himself was a whirling dervish. That I enjoyed very much.

In 1940 Pro-Arte brought the Jooss Ballet. They did some things that were humorous, they did one that was like a fairy tale, with fantastic costumes [A Spring Tale]. And A Ball in Old Vienna and The Big City. And they did The Green Table. That was potent, to say the least. Ernst Uthoff was the Standard Bearer, but anyone who has seen Rudolf Pescht as Death will never forget it. I was sitting at the edge of my seat. It was fantastic. And then the light effects — the spotlight starts getting smaller and smaller, and just the face.

Ted Shawn’s Labor Symphony, 1930s, Jacob’s Pillow Archives

But that was a revelation of what you can do with modern dance. Kreutzberg is one man doing it. With Shawn they were all men and it was exciting to see. But this was a company of men and women. There was so much variety in the company. You have something as powerful as Green Table, and the Big City is very deep, but these nasty things that happen. And then you have the Seven Heroes, which was funny, with cheerful peasants.

WP: Jooss had already fled Germany? Where was he living?

GF: The Jooss Ballet and the Comedie Française came to Cuba because they were running away from the Nazis. Jooss took up residence in England with the company, and they were touring mostly the Americas. Ernst Uthoff, the father of Michael Uthoff, opened a school in Chile. I also saw Ballet Theatre in the mid-40s. They did Agnes de Mille’s Tally Ho. That was a lot of running around. I don’t know who was chasing who, but someone must have been chasing an imaginary fox. And in 1948 Ballet Alicia Alonso came with Coppélia, which Leon had staged for them. They also did Peter and the Wolf [the one choreographed by Adolph Bohm]. Melissa Hayden was a very charming bird; Cynthia Riseley was a sinewy cat, and Dulce Wohner, a product of Pro-Arte Musicale, was a very funny duck. Then unfortunately there were some politics in Pro-Arte and Yavorsky left. They brought in Georges Milenoff, a Bulgarian who had been in Ida Rubinstein’s company. In the meantime de Basil came back with a more extensive repertoire, but Danilova, Toumanova and Massine were not with the company. Baronova came but she danced only two performances. This time they had Coq d’Or, Swan Lake, Petrouchka,and Paganini.

One of the best things they did was Balanchine’s Cotillon. That was beautiful. It’s about the relationship between the young men and the young women at a ball. It had fabulous costumes and scenery by my favorite designer, Christian Bérard. I am kind of sorry that Balanchine never staged it for the New York City Ballet. It has mystery like Ravel’s La Valse. The “Hand of Fate” pas de deux is beautiful and unusual.

But then we had enough time to see a lot of Basil because the company went on a strike, which was considered by some to have been the beginning of its end. [See Vicente Garcia-Marquez’s book The Ballets Russes, p. 272.]. Half the company left Cuba, and the other half stayed with Basil in Havana for four months. They didn’t have money, of course. Yurek Shabelevsky came to join them, and Alberto Alonso and his wife, who had left the de Basil company in 1940, came to help them out. She was Canadian, with fantastic technique. Her name actually was Patricia Denise Meyers, but she was called Alexandra Denisova.

Jasinski in Cuba, 1933

We saw them in class and in rehearsals. It was amusing to see Serge Grigoriev, who had been the regisseur for Diaghilev and for de Basil, demonstrating a dance in the Beau Danube that Danilova had left. (I think it was Olga Morosova who had replaced her.) He was a big man, not very young, and holding up his pants. And there was his wife, Madame Lubov Tchernicheva, who had been with Diaghilev. Another ballet that they did was Schéhérazade, and she was Francesca in Francesca da Rimini by David Lichine. Tatiana Leskova was the girl in pigtails in Lichine’s Graduation Ball and she was wonderful and very funny. And so we had those Russians there for three months.

We became close friends with Roman Jasinski, Yurek Lazowski, and Paul Petroff. I remember Jasinski’s wife, Moussia Larkina (originally Moscelyne Larkin; they later co-founded Tulsa Ballet). She was about 15 years old. She’s American Indian, very round face, two pigtails, dark, a very good dancer. Afterwards she was dancing with Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo, the other Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo [headed by Serge Denham].

WP: Were you able to take classes when they were in Havana?

GF: I took classes with Paul Petroff. He gave me my first pas de deux class. He taught me the adagio from Swan Lake and the nocturne from Les Sylphides. In the meantime Milenoff started rehearsing Carnaval. I was Columbine. We didn’t have many male dancers so my Harlequin had to be a female Harlequin — who happened to be Alicia’s older sister Cuca.

Baronova in Les Sylphides*

WP: Did you ever want to dance with Basil’s company?

GF: Oh, I would have loved to, but I was not even in high school and my mother wouldn’t have let me anyway. But Pro-Arte kept bringing the Metropolitan Opera, and I danced with the opera. I was in Aida and the Gioconda. And I danced also in Rigoletto and Carmen.

WP: And who choreographed these?

GF: Alberto did one. The “Dance of the Hours,” in Gioconda, I think, was his wife Pat. Aida I think Alicia did, because when Alicia had the eye problem, she couldn’t dance and was staying in Cuba.

WP: When you finished high school what did you do?

GF: I stopped dancing.

WP: Why?

GF: There were no other schools outside of Pro-Arte except what I call the twinkle-toes type of school. After that, Milenoff left. Alberto Alonso’s mother had become president of Pro-Arte’s musical group, so Alberto took over the school with his wife Pat. I realized later on that Pat was only about two or three years older than I was. Actually, it blew my mind also when I saw the first Basil company — I was 11— that those dancers that I thought were so sophisticated like Baronova and Toumanova, were only a few years older than I was.

Pat was very young but she was a tremendous technician. She had taken over most of Baronova’s roles. Then they started teaching character classes and pas de deux classes around 1940, maybe ’41, ’42. So the school was taking a different shape. Then we started doing the repertoire: Aurora’s Wedding, Les Sylphides, Petrouchka. Pat had just left the company; she had been one of the principal dancers for several years. She made a big mistake [by marrying Alberto] because that truncated her career as a dancer at only 18 or 19 years old. Tremendously strong technician — she could turn to the right, to the left, she could turn on her toes, she could turn on her head.

WP: Where was she trained?

GF: In Canada by a very good teacher, June Roper from Vancouver. Many good dancers came from there. And so it was fun to do Aurora’s Wedding. I was doing the Bluebird but with the original choreography, not the Yavorsky or Milenoff. I was doing the real thing. We danced Les Sylphides — the Fokine Les Sylphides, and it was very exciting. But then Alberto divorced Pat, and there was a big change, so I just didn’t want to continue. That’s when I went to law school.

WP: In Havana?

GF: Yes, in the university. One of my classmates was Fidel Castro. We didn’t have high school. We have the European system. It’s five years. Tough. There were no choices. I take two credits of this and one credit of that. It was very difficult.

WP: What was Fidel Castro like as a classmate?

GF: I don’t know because he was into politics, and I was into having a good time with my friends. But he was a very good student and was already involved in politics. He was always in this or that organization or going to Santo Domingo to overthrow the president. I was studying diplomatic law. I missed dance, but there was no place to go. Finally I found out that Anna Leontieva, from de Basil’s company, had stayed in Cuba and opened a small school. By the way, that’s really is her name. Beautiful dancer.

I was talking a couple of years ago with Tatiana Leskova, who was one of the dancers stuck in Cuba during the strike, and Lichine. They had to make some money, so Lichine got an engagement to do a show in the Tropicana, which was the biggest nightclub in Havana. (It still exists.) The show was called Conga Pantera — the panther. The panther was Tatiana Leskova, poor thing, and they used to throw her from one tree to the other. But they had to pay the rent. She’s wonderful. She’s the one who staged Présages for us.

WP: And she came up to Jacob’s Pillow to stage Massine’s Les Presages for the Russian-American student program in 1991.

Baranova practicing Choreartium in her dressing room, 1933*

GF: And she did also Choreartium. My favorite of all the symphonic ballets, which is unfortunately lost, is Symphonie Fantastique. Ah, what a beautiful ballet! The Berlioz music is beautiful. Again, costumes and scenery by Christian Bérard. [Unbeknownst to Gloria, there is a 1948 film of it danced the Royal Danish Ballet dancing it.]

WP: So how did you get back into dancing?

GF: I went to Anya’s studio. Anya [Leontieva] had been trained in Paris Opéra Ballet, but her mother, Genia Klemenskaya, who was in the Diaghilev company, came too. She reminded me of Maria Swoboda, yelling her head off all the time.

I came to New York for the summer. It was during the war, 1944. Alicia had studied with Mme. Alexandra Fedorova, and she used to say to everybody, “If you go to New York, you have to study with Mme. Fedorova.” (Annabelle Lyon had told her about her.) But when I was in New York and I wanted to study with Mme. Fedorova, Mme. Fedorova was in Chicago with Leon Fokine, her son. It’s a twist of fate that I never studied with her, and then she became my mother-in-law. So I studied with her in the dining room!

I wanted to study with [Anatole] Vilzak, but he was on vacation, so then I went to study with Sviacheslav Swoboda. The main students there were the Tyven girls, Gertrude and Sonja. Gertrude was the principal dancer of Denham’s Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo. That summer I saw that company do Balanchine’s Danses Concertantes with Danilova and Freddie Franklin. I kept going to Anya while still going to Havana University.

Then, in 1948, Ballet Theatre closed for one season because of financial difficulties. So Alicia and her husband Fernando rounded up a bunch of dancers from Ballet Theatre including Igor Youskevitch, Melissa Hayden, and Barbara Fallis, and came to Cuba with the idea of starting a company, with Pro-Arte as headquarters. Pro-Arte gave them the space, the costumes, the scenery, the orchestrations — everything. Alicia asked me to join; she needed a few Cuban dancers for Swan Lake. (Her company was called Ballet Alicia Alonso, and after the revolution it became Ballet Nacional de Cuba.) I said no because I was not in shape. Alberto Alonso left with the company on their tour to South America, so Pro-Arte had to have a new teacher, and they brought Leon Fokine [son of Alexandra Fedorova and Alexander Fokine, Michel’s brother]. So I started taking class to get back in shape. But I never got into the Alonso company because we got married.

WP: What do you remember about Leon’s classes?

Leon Fokine with Vera Volkova, at the Harkness Ballet, 1964

GF: They were fantastic. He taught me how to plié. I used to have a tremendous jump, but how to do plié, how to hold the arm, how to hold yourself, how to present yourself — he taught me that. We got married in 1949 and, after a short time in New York, we went to live in Washington, D.C. He was engaged to teach for a big school there that was the competitor of the Washington Ballet. And then the lady who owned the school decided to sell it, and Leon bought it. We were there from 1953 to ’61.

WP: Did you have any students who later became professional?

GF: Yes, Lili Cockerille [later Lili Cockerille Livingston, author of American Indian Ballerinas]. Lili was the prettiest little girl, had bright red hair. She was always spotless, with her little leotard, her tights were spotless, her ballet slippers, the hair in a little bun with flowers around it.

WP: I remember her as an advanced student at SAB, around 1960, when I was there for the summer. I would watch the advanced class, and she was one of my favorites.

GF: Yes. That’s before she joined the Harkness. Washington is a wonderful city, but the restaurants closed early. Once after a performance Alicia and Igor [Youskevitch] and I went out to have dinner. We wound up in a Whelan Drugstore having grilled cheese sandwiches.

Alicia Alonso with Igor Youskevitch, ph Sedge Leblang, Dance Magazine Archives

WP: Were you in Washington when Castro led his revolution that took power?

GF: Oh, yes. Almost every summer Leon used to go and teach at Ballet Alicia Alonso in Havana, and I took company class. Once I went, I hadn’t been home in three years. The company was going to South America, and Alicia asked me to come with them. But I hadn’t seen my mother in three years, so I said no. Castro was already in power and it was my last trip to Cuba. I had a big class reunion with my friends from school because it was my birthday. It was the last time I ever saw my schoolmates, because then everybody was leaving Cuba and going to different places. It was getting harder for Cuban citizens to leave, and I was still a Cuban citizen. But I was a U.S. resident, however, and so I could leave.

I came back to Washington. One day Fernando Alonso called to say they were going on tour to the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe and he wanted Leon and me to go with them, Leon as ballet master and me as regisseur.

WP: This is for Ballet Alicia Alonso?

GF: No, Castro was already in power so it was Ballet Nacional de Cuba. There are these posters for Ballet Nacional de Cuba’s Coppélia, saying “choreography by Leon Fokine.”

WP: So, did you go with them to Russia?

GF: Yes. Leon, who hadn’t seen his brother Nicholas in thirty years, was very interested. But we had to find somebody to stay at the school. So finally we came to Havana and started working. They wanted me to dance, but Leon wouldn’t let me. He had a previous relationship with a dancer who was always on tour, and he said, “No, no, no, I want my wife with me.” I agreed to it. What could I do?

We went to Russia but Leon had ulcers. We went to Riga [where Leon had lived and had danced with the Riga Opera, where his mother was ballet director], we went to Moscow, we went to Leningrad. And we went to Poland and Germany. When we got to Berlin, Leon had to have surgery. I stayed with him for a couple of days but then I had to leave to Leipzig. I came back to Berlin and he told me, “I don’t want to go back to Washington.” Hallelujah! Anyway, because of his surgery I had to leave the company, also because the company was going to China and I was not an American citizen. So we came back to New York. I went to Washington to settle the school and Leon was here.

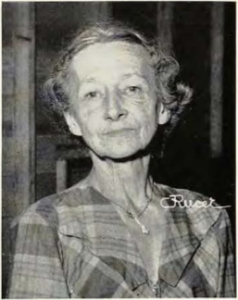

Alexandra Fedorova in 1962

WP: And then in New York did you take classes with Fedorova?

GF: Oh, yes, I took many ballet classes with Fedorova. Even when we lived in Washington we’d come to New York and I’d go take class with her and sometimes with Vladimir Dokoudovsky also. He taught at Carnegie Hall.

WP: So what did Leon do when he came back to New York?

GF: Looked for a job.

WP: Did he do Radio City then?

GF: No, no, no, he was in Radio City before I met him, during the Depression. Rebekah Harkness wanted to take private ballet lessons, and Leon’s friend Jeannot Cerrone, who was manager of Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo and Ballet Theatre, got him the job. When he lost the job at Harkness, he taught at Irine’s.

WP: Yes, he taught at Irine Fokine School of Ballet in Ridgewood, New Jersey [where I studied]. I remember him as a strict teacher. So was he part of the beginning of the Harkness Ballet?

GF: Very much so. I was there too. Mrs. Harkness asked Leon to come watch the audition for her new company with Joffrey, and I went with him. When Harkness got together with Joffrey and went to Watch Hill, Rhode Island the summer of 1962, we spent the summer there. As a matter of fact I won a prize in a contest. Rebekah wrote music and Donald Saddler choreographed it, which had the black bottom and every social dance up to the twist. And my partner was Bob [Joffrey], appropriately.

WP: Yes, Bob was small too.

GF: We won second prize — the first prize was won by Mrs. Harkness! We got to perform it two times.

What she wanted was to do the Rebekah Harkness Ballet with Robert Joffrey as the director. But Bob Joffrey worked too damn hard to have his own company, not just to be the director of somebody else’s company!

WP: So you were on his side.

GF: Absolutely. Leon went on working with Harkness for several years more. I sympathized with Bob. [Joffrey struggled to remake his company after Rebekah Harkness started a company in her name with his dancers.]

WP: You once told me that what you liked about Leon was something about the arms.

GF: Yes, because they’re one hundred percent Leningrad, Imperial Ballet — that openness. Leon trained there, and that stays with you.

WP: So when you got to New York, Leon was teaching at Harkness and you were teaching sometimes at Irine’s school?

GF: I was teaching there from 1961 to ’74.

WP: I understand you studied with Olga Preobrajenska in Paris.

GF: Being a Cuban girl, I lived in the House of Bernarda Alba, a very Spanish family. There’s no such a thing as independence. You’re always dependent on your mother or your father or your grandmother or whoever. When I got married and came to New York for a day, I didn’t dare to leave the house by myself. The Royal Ballet came to Washington and a very dear friend of ours was with them, Svetlana Beriosova, who said, “Oh, you have to come and visit us in London.” So I asked Leon, “Is it okay if I go?” He said “Sure.” And Svetlana said, “Well, if you’re going to London you might as well go to Paris, and if you go to Paris you might as well go to Rome and Venice and Florence.” So the trip mushroomed to be a three-month affair. This was before air flight, and she said, “Of course you have to travel on the Ile de France.” Everything was so exciting and the kids in the studio gave me parties and presents. And then I got cold feet and said, “How the hell am I going to go Europe?” And so I came to New York first. My friends Sally Edwards and Marlene Rizzo—she’s Helgi Tomasson’s wife — took me out to dinner and to the hotel—it was my first time staying at a hotel alone.

WP: So you made it to Paris and you studied with Preobrajenska.

GF: I made it to London, I made it to Paris, I loved it. I studied with Preobrajenska for two months.

Preobrajenska

WP: Tell me what you remember about studying with her.

GF: She was tiny and very old by then. She always wore a maroon-colored jumper with a little crocheted blouse underneath, wrinkled stockings, and ballet slippers with ribbons. She would try to do entrechat quatre and she couldn’t get off the floor. When she explained how to finish a pirouette, she would open her arms, like saying, “Here I am — how beautiful.” At the end of the adagio, she always had a very dramatic pose, like putting your arm on your forehead like you’re suffering. Oh, but if you point that foot in the back, she’ll kill you. “You’re not dancing now; you’re acting. You don’t point your toes.” She was very persistent! That was one of the most thrilling experiences — just to listen to that woman and see her move.

WP: When did you get the job as the photo archivist at Dance Magazine?

GF: Leon died in 1973. In 1978 I opened my own school in Brooklyn Heights, and that’s where I met Marilyn Hunt. I was planning with Marilyn to include dance history classes. But then it was 1984 and everybody’s leases were not being renewed. The school was doing fine. I opened with 50 students and in four years I had 125. But my lease was not renewed. I went to teach for Richard Thomas. His studio was in the former School of American Ballet.

WP: …where there’s now a Barnes & Noble.

Richard Thomas and Barbara Fallis in an undated photo

GF: Yes, and I loved Richard. We knew each other from Cuba because he was in Ballet Alicia Alonso with Barbara Fallis, his wife. (Actually I think his son was born in Cuba. I remember Richard, the son [the actor], in a little buggy as a baby.) But he lost his lease. Dokoudovsky lost his lease. David Howard lost his lease. Finis Jhung. Everybody. There was no place to go. I did not want to leave New York. I’m sorry, but I’m a New Yorker one hundred percent. I didn’t know what to do. One day Marilyn Hunt [a former student of Gloria’s who was an editor at Dance Magazine] and called me up and said, “How would you like to work in Dance Magazine.” I said “Marilyn, I have never worked in an office in my life.” She said, “Well, it’s the photo archives.” That was from 1985 to 1999. After that, Richard Thomas arranged for me to be ballet master at the Universal Ballet Company in Korea. So I spent three months there. They pay very well and treat you like a queen.

WP: You said that you recently [2004] sat down with Alicia and talked.

GF: We reminisced about Yavorsky because he was her first teacher, and about our friends at that time.

WP: I’ve heard that she’s on very good terms with Castro.

GF: Oh, yes. She has government subsidy. If she didn’t have Fidel, she wouldn’t have a company. When I was in Havana University law school, almost every one of my classmates, if there was a ballet performance, used to go to see it.

WP: So it was more part of the culture than it is here.

GF: Yes.

WP: Why do you think Ballet Nacional de Cuba has had such international success?

GF: Well, it had damn good dancers, trained in the school. Everybody talks about the Cuban school, the Cuban school, but it’s the Russian school! It started with Yavorsky; it was started with Milenoff; it started with Fedorova. Cuba was friendly with the Soviet Union. Do you know how many teachers from the Bolshoi and from the Kirov were in Cuba teaching? Of course it has a different flavor. We’re Latins; we have a different feel for the music than the Russians. But basically it is the Russian school. The only trouble now, they’re losing a lot of dancers.

WP: Yes, they’re defecting. Why?

GF: Living conditions in Cuba are terrible, and the dancers don’t get paid well. There’s no water in the city, even if you have any Cuban pesos. It was in the newspaper here that they pay in Cuban pesos, but you cannot buy anything with Cuban pesos in Cuba. Even if they have a million pesos, they cannot eat in a restaurant because you have to pay in American dollars. You buy food with dollars; you buy clothes with dollars. There’s nothing — you cannot buy even a safety pin without dollars.

WP: Where else have you taught?

GF: Tim Wingerd, who had opened a dance conservatory in Albuquerque, invited me to come and teach ballet, and especially character. So I spent a wonderful two months there. He invited me to stay in New Mexico as the head of the ballet department, but unfortunately he passed away.

WP: When you teach, what do you emphasize?

GF: You have to have technique. But also you have to have feeling, and a good ear for the music. The dancers in the de Basil company, their technique was nothing compared to today, but they danced from here [touches her heart].

WP: When you were teaching at Irine’s, you set Les Sylphides on us. Whom did you learn Sylphides from?

GF: In Cuba, from Pat Denisova from the de Basil company, which is the same Sylphides because it was staged by Michel Fokine himself.

WP: Did Leon stage any of the Fokine ballets?

GF: No, I don’t think he knew the choreography.

WP: So there’s only Vitale [Michel Fokine’s son] who knows them? And what was the relationship like between the cousins — Vitale and Leon?

GF: Like brothers. They were both born in December of the same year, in the same house. I think they were even thrown into the same crib. They lived together, Fedorova and her husband, Alexander, and Michel and Vera, in the same house.

WP: What’s the relation between Chopiniana and Les Sylphides?

GF: Fokine did two Chopinianas. The first one was completely different from Les Sylphides; it had character numbers. One scene was a Polish wedding. In the first scene, the Nocturne is sort of similar to Symphonie Fantastique, the third movement. There’s the Poet and the Muse and then there’s a tarantella; it’s Chopin music but it’s a tarantella. The only thing that is left from that Chopiniana was the waltz that he choreographed for Pavlova and Oboukhoff — not Anatole Oboukhoff, but the older Oboukhoff, Mikhail.

Les Sylphides with Roman Jasinski 1940

WP: Anatole Oboukhoff is the one who taught it at SAB [School of American Ballet].

GF: Yes. That’s not the one. The older one saved it and incorporated it in the second Chopiniana, which is what we know as Les Sylphides.

WP: What do you think should happen with the Fokine ballets?

GF: I don’t know. I wish that they would continue. Alicia was very upset. She wanted to do Sylphides at City Center in 2001. The Ballet Nacional de Cuba has a wonderful Sylphides. But she couldn’t do it because a few weeks before, Isabel [Vitale’s daughter, Michel’s granddaughter] signed a contract with Ballet Theatre that gives them the exclusive rights to do Sylphides in New York I think for two years.

WP: What is it about Fokine ballets that are different from other ballets?

GF: Fokine was very Russian; his ballets like Schéhérazade are supposed to be Oriental, but Russian. I was married to a Russian for a long time. Their philosophy is Oriental. They’re not Western in their thinking. Don’t forget the Tartars were there for many years, so their way of thinking is fatalism. His choreography is very Russian. Some of the ballets are dated, like Paganini.

WP: And what did you think of the way the Joffrey did Petrouchka a few years ago?

GF: Well, that’s another problem. Petrouchka, Prince Igor — they will never be done right until you get character dancers. With de Basil it was exciting to have all these Polish boys like Shabelevsky and Lazowski and Nicolas Orloff.

WP: Oh, I studied character with Orloff at Leila Crabtree’s studio around 1960!

GF: He was the best Drummer Boy that’s ever been in Graduation Ball. Most of the company was character. They had three classical dancers: Paul Petroff, [Roman] Jasinski, and then later Michel Panaieff. Everybody else was character. Shabelevsky, the greatest of them all. And good-looking — oh! Gorgeous. Lazowski, he was teaching character later at ABT’s school. There was Marian Ladré and Narcisse Matouchevsky. They’re all character dancers.

Narcisse Matouchevsy and Yurek Lazowsky on the beach,1932*

When I see the Joffrey Ballet’s Petrouchka, and the Coachmen are dancing, the Nursemaid comes and they start taking off their jackets, you have to tease a little. That doesn’t come through. Prince Igor — I’ve seen it and it’s dead. They do the steps, but they lack the fire of true character dancers, the fire of the Polovstian warriors.

WP: Thank you, we’ve covered a lot of ground. It’s been a long trip into the past.

GF: I might not sleep tonight.

≠≠ END ≠≠

Postscript: Sometime after this conversation, I took Gloria to New York City Center to see the Ballet Nacional de Cuba. Her eyesight was so bad she was legally blind. In intermission, I brought her over to where Alicia Alonso, who was even more blind, was sitting. The two talked animatedly about dancing in Havana when they were young. Then they joked about not being able to see well because they both would rather see their memories of ballet than whatever was onstage in the present anyway.

* These photos are from the book Irina Baronova and the Ballets Russes de Monte Carlo by Victoria Tennant.

Special thanks to Victoria Tennant, Robert Johnson, Norton Owen, and Ballet Review.

Historical Essays 8

It’s a strange, unsettling thing, but disaster can be visually beautiful. In a monumental new book called

It’s a strange, unsettling thing, but disaster can be visually beautiful. In a monumental new book called