This story was originally printed in Dance Magazine, December 2000. When I included it in my first book, Through the Eyes of a Dancer (2013), I wrote this little preface:

When I joined the editorial team of Dance Magazine, I was asked, What is the issue we are not covering? My immediate answer was AIDS. The disease had ravaged the dance community, yet not much had been written about it in the magazine. I was devastated when my friend Harry Whitaker Sheppard died in 1992, and that was just one death of thousands. Working on this story immersed me in the sadness and anxiety we all felt. But it was galvanizing—and uplifting—to hear what these six dance artists, all of whom had contributed much to the field, had been through and the courage they called upon. By 2000 there was some good news: people who had found the right combination of meds were living with AIDS a long time.

— + —

I was riding in an elevator in a Manhattan hospital, and the elevator doors happened to open onto a ward in which a distraught young man was talking into the phone at the nurses’ station. I recognized him as a fellow choreographer—Arnie Zane. I knew Arnie had AIDS, and I stepped out to say hello. He had just learned that his chemotherapy wasn’t working and the doctors were telling him there wasn’t much hope. He was crying, and I hugged him. That was all I could do. As we walked outside, he lamented, “I know I complain a lot, but I love this life and I don’t want to die.” A few months later, Arnie, like so many others, left us.

That was in 1987–88. If this scene had happened today, there would be more hope.

In the eighties and nineties, the dance community was decimated by AIDS. We lost some of our most treasured elders: Alvin Ailey, Robert Joffrey, Rudolf Nureyev, and Michael (A Chorus Line) Bennett; some of our most promising youths: Edward Stierle of the Joffrey and Peter Fonseca of American Ballet Theatre; and mid-career artists like Arnie Zane (whose memory is preserved in the name of the Bill T. Jones/Arnie Zane Dance Company), Louis Falco, Robert Blankshine, Christopher Gillis, John Bernd, Harry Sheppard, and Ulysses Dove. During that period, it seems, we were attending as many memorial services as dance performances. We learned the meaning of community—the gathering together when the loss of someone you love leaves a big hole.

But thanks to improved medication, testing positive for HIV is no longer a death sentence. More dancers are continuing to live and dance with the virus. Others are still having a hard time. The fatality rate is slowing, but we cannot forget the devastation the disease still brings. I spoke with six dancers and former dancers who are handling the disease in different ways.

Dancer/choreographer Neil Greenberg, who teaches at the State University of New York at Purchase, tested positive in 1986. He’s been basically asymptomatic, so he is living his life as usual, only cutting back on alcohol. Greenberg says 1993 was a hard year for him: his brother died of AIDS, two-thirds of the people in his HIV support group died, and he learned that the virus’s presence in his blood had increased. Out of these tragedies emerged his Not-About-AIDS-Dance (1994), a powerful work that created a buzz in downtown New York.

Greenberg in 2018, photo by Paula Lobo

But in 1997 he landed in the hospital. “I had high fevers the whole week I was performing that fall,” he says. “About a year later the doctors realized it was the medication that was doing that to me.”

Now on new medication, he is thriving again. All along, he says, he has maintained a positive approach. “I tried to deny what all of the papers said, which was a ten-year maximum life expectancy,” Greenberg says. “I refused to believe that and, as it turned out, I was right, for myself.” However, he still struggles with the disease emotionally: “The whole AIDS-as-punishment thing is hard to get rid of in the deepest layers, and I probably haven’t.” In order to dispel some of the stigma that he grew up with, he makes a point of telling his freshman students at SUNY Purchase that he has the virus. After all, he reasons, it’s part of their education.

Another dancer I spoke with performs every night in a high-powered Broadway musical. He has asked that his name be withheld, so I’ll call him Jack. Jack got the bad news in 1996, the year that new medications came into being and many AIDS patients found “cocktails” of a variety of medications to be effective. Jack says, “My doctor told me right away, ‘This isn’t the end of your life. Don’t drive your car off a cliff. There are medications that are helping people, and you should be able to live a normal life. It’s a controlled disease like diabetes. You just have to take your pills every day.’” At first Jack balked at telling his fellow dancers. But, he said, “I’ve never had a bad reaction from people I’ve been working with, though it’s scary at first. You’re afraid that people will look at you differently. But I don’t mind being out at work, because people have questions and they know they can come to me. I enjoy giving back whatever I can to people around me.” He’s been generally very healthy, but his doctors haven’t always known what to prescribe: “One time, for a whole month, I couldn’t leave the couch: vomiting, diarrhea, severe stomach cramps. It was very scary.”

The knowledge of his HIV status actually motivated him. “It made me pull my life together and get my career going. I was happy doing revues and competitions, but I decided I wanted to make Broadway. Within three months, I made Broadway.”

He feels comfortable in the dance world. “Being gay in the dance world is more accepted and you can be who you are. Because of that, people who are [HIV] positive can come out and share that also. When you get into tv or film, being gay is not OK. They may hire you to be a gay character, but they want you to be straight. If they were to find out you’re HIV [positive], they would probably not hire you.”

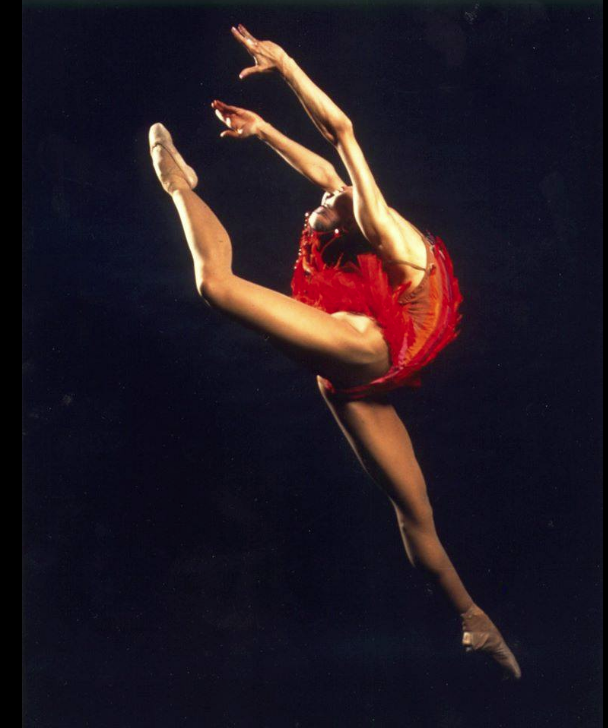

Of course, not only gay men get the disease. Stephanie Dabney, former star and unforgettable Firebird with Dance Theatre of Harlem in the early eighties, was diagnosed ten years ago. Her first thoughts were, “There goes my career. If I get too sick to dance, what am I going to do? How am I going to tell my brother and sister?” She spent all of 1996 in the hospital with recurring pneumonia, and the following year in nursing homes. “My fourth pneumonia was PCP [pneumocystis carinii pneumonia, a life-threatening infection for people with weakened immune systems], and my lung collapsed. I had a chest-tube pump in me for eight weeks. I remember the doctor coming into my room, surprised, saying ‘Hi, I didn’t think you would be here.’ He thought I wasn’t going to make it through the night! That freaked me out.” She is now participating in an experimental program, a nine-month trial with an Italian physician. “Maybe I’ll help him find the cure,” she says. Friends encourage her to resume dancing. “I ran into [actress] Cicely Tyson, and she thinks I should dance again,” she says. “But Arthur [Mitchell, DTH’s artistic director] has young, healthy, and eager dancers now, and there’s nowhere else I would want to dance besides DTH. I can’t imagine trying to get in shape. I’d rather be remembered as the Firebird when I was young and healthy.”

Stephanie Dabney in John Taras’s Firebird

Sometimes nondancers would turn against her when they found out she had AIDS. “There was a woman in Atlanta whose position was to wine and dine the Somebodies,” Dabney says. “I was the black ballerina who did Firebird, so I was in her in-crowd. But when she found out I had it, she wouldn’t even return my calls.”

Dabney, who has taught at Spelman College in Atlanta, thinks about the future. “I thought I’d want to teach again, but I’m walking with canes now. Tanaquil LeClerq [the extraordinary Balanchine ballerina who was struck down with polio in 1956] was my favorite teacher. She used her hands and arms as legs and feet.”

Another former dancer, Joseph Carman, is now a freelance writer. Carman, who has danced with American Ballet Theatre and the Joffrey Ballet, almost died four years ago before the new medications became available. He had been diagnosed in 1987 while dancing with the Metropolitan Opera Ballet. “I kept it secret in the beginning because there was such a stigma. That was the time when The Post was running headlines like ‘AIDS Killer.’ There weren’t many support groups around. The year before I left the company, I told the ballet mistress, Diana Levy. The Americans with Disabilities Act had just been approved, which protects anyone in the work force who has a disability. It allows people with HIV to shorten work hours or to do a less demanding job. She was understanding and would ask me during rehearsal, ‘Are you OK?’ ” The main thing for Carman was getting enough rest. Working on a new production, he’d sometimes be in the theater for twelve hours: “When things were bad, I’d break out in shingles.”

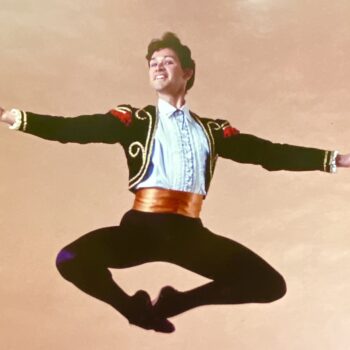

Joe Carman in ABT’s Don Quixote, early 1980s

In 1996, he was diagnosed with Kaposi’s sarcoma (KS), a cancerous growth associated with AIDS. “It progressed slowly and then all of a sudden my immune system went like a house of cards. I’d wake up with two new lesions every day. It was terrifying. They discovered I had KS in my lungs. That usually means a year to live if you’re lucky. The doctor put me in the hospital and administered heavy-duty chemotherapy. I call it ‘slash-and-burn’ chemo because it wrecks everything. For days afterward I would feel like crawling out of my skin. But it did get rid of the tumors.”

An AIDS conference in Geneva had just demonstrated that protease inhibitors and the new “cocktails” were helping people. It was good timing, and Carman started a regimen of the new medications. “My immune system slowly started to rebuild itself, and my T-cells [white blood cells that help suppress disease] climbed from ten to over six hundred. It’s truly miraculous.” But it wasn’t easy emotionally. “I thought I was dying, and then all of a sudden I wasn’t dying. I was in shock for about a year. Physically, it took me four years to feel like myself again.”

Joe Carman now

But Carman has been through a significant shift. “When you come that close to death, it changes the way you look at things. It’s like a rebirth; it cuts the bullshit factor. For me now, the quality of life is important: eating well, walking my dog in the park, spending time with my boyfriend. I still do a juggling act with all my medications.”

Carman feels that consciousness has been raised and there is less stigma about the disease. He is grateful for the concern of people in the dance world. But the past is a string of sorrows. American Ballet Theatre’s 1977 video of The Nutcracker starring Mikhail Baryshnikov and Gelsey Kirkland used to be broadcast on TV every Christmas. He says, “I can’t even watch it now because half the dancers in it are dead.”

Chris Dohse, a dancer/choreographer/writer who is also a proofreader, is torn between submitting to the new medications and just letting himself slide downhill. “I don’t know if I want to buckle myself into the regime of the new cocktails. I don’t want to go through that ordeal.” Dohse, who tested positive in 1987 when he was dancing in Washington, D.C., was put on azido-thymidine, or AZT, in 1990. AZT inhibits the spread of the AIDS virus, but it can have debilitating side effects. “I felt terrible every single day of that year,” says Dohse. “It makes you tired, nauseous, headachy, dizzy, and run-down. During that time they were finding that it works better if you take less of it. I got disillusioned and distrustful, so I don’t believe anything the doctors say.”

Chris Dohse in a dance by Nancy Havlik

But for Dohse too, the news was at first a motivating factor: “Knowing I had the virus made me stop fiddling around. I stopped dancing for other people and started making my own work.” Like Greenberg, he used his despair creatively. “I made a big dance for nine people that was going to be the final thing that I gave to the world. I kept revamping it. I didn’t want to finish it because then it meant I was going to live, and have to make other work. This was supposed to be the everything-I-have-to-say piece.”

He lost the few romantic figures in his life, which has left him with a sense of alienation. “Mostly I feel anger that I didn’t get to go with them. They had these memorial services and dramatic narrative arcs, but I have to stay here and turn gray and have my teeth fall out and pay back my student loans. I’m lonely.” Medically, he’s not up for the new round. “They started saying I should take new medication to reduce my viral load. They said that to me in 1990 with the AZT, my blood data will improve but I’ll feel awful.” His T-cells are under a hundred, and, after thirteen years, his viral load has gone sky high. Looking back, he says, “Eight years ago the data showed that thirteen years was the longest anybody had lasted before they started getting sick. I thought: Okay, I got five years left; I’ll make a five-year plan. For eight years I had made six-month plans. I would have gotten a college degree back then if I wasn’t going to die any day. I danced instead, thinking I’d go out in a blaze of glory. Little did I know I would keep lingering. I’m the boy who cried wolf because I’ve lived so long on this edge of despair.”

Christopher Pilafian with Argos, 2021

Christopher Pilafian, on the faculty of the University of California at Santa Barbara, has found some measure of peace. He danced with Jennifer Muller/The Works from its inception in 1974 to 1989, eventually serving as associate artistic director. Now 47, he says, “It’s hard to tell whether what I’m feeling is a result of the virus or of the natural aging process. I’m a little more methodical, less rambunctious now.” Four years ago, he improved his T-cell count tremendously with the new medications.

Pilafian feels fortunate to have colleagues who are sensitive to his condition. “When I was having a bad time, they were available to cover classes for me.” He mourns the toll the virus has taken on the lives of dancers he admired as well as on his own. “The middle years are an important period in a dancer’s life: you’ve still got your chops and also your independence. I would like to have seen what Louis Falco would have done, had he lived past 50. If I weren’t HIV positive, I might have focused on my work as a choreographer. Instead, I had to go into self-preservation.”

In 1989, he attended a seminar that redefined AIDS not as a terminal illness, but as a manageable chronic infection. “To take the assumption of fatality off the diagnosis is very powerful. Now I’m doing things that support life: meditation, visualization, eating well, and watching the purity of things. There was so much fear about the available medicines at that time. To deal with that, I used what I knew from dancing: imagery. I began to visualize the medications as rainbows, waterfalls, and light.”

Pilafian and Nancy Colahan, at the end of their collaborative duet Dream Dancing, c. 2010

“At the conference we were asked, ‘What is this apparent misfortune bringing to you that is a benefit?’ It gave permission to look at your life in a different way. You could imagine the endpoint being closer. Then starts the dropping away of the nonessentials, which is a sacred, life-sustaining process.”

— + —

These six dancers are, like the rest of us, many-faceted people. One of those facets, surely, is tremendous courage. Another is hard-earned wisdom. All of them agree on one thing: the need to tell young people to take precautions. Anyone can contract the virus from sexual activity, and drug users can get it from using a contaminated needle. Although a broad range of treatments is now available, not every patient does well on them, and the side effects can be devastating. The ultimate message is one of prevention: inform yourself, protect yourself, and have only safe sex.

Updates:

- Joseph Carman, a senior contributing editor at Dance Magazine, has written about the performing arts for Playbill, the New York Times, the Los Angeles Times, the Village Voice, the Advocate, and many other publications. Now in stable health (and juggling many medications), he is the author of Round about the Ballet and also teaches various styles of yoga, including vinyasa, hatha, and restorative. Update 2021: Now living in Palm Springs, Joe continues to teach yoga, including chair yoga for survivors of HIV. He writes occasionally and serves on the committee for the Dance Magazine Awards.

- Sadly, we lost Stephanie Dabney in 2022. The NY Times obit is here.

- Chris Dohse has worked as a copywriter and editor for several major pharmaceutical ad agencies in New York. His life performing, choreographing, and writing criticism has become an avocation. He is currently on disability, dealing with the effects of multiple medications and co-morbidities. Update 2021: Chris lives in upstate NY, writes poems and monologues and takes walks in the woods. His drawings are on display at Visual AIDS.

- Neil Greenberg is a professor of choreography at Eugene Lang College, The New School of Liberal Arts in New York City, where he continues to choreograph and dance. Though he had a run-in with an AIDS-related complication (Castleman’s disease of the lymphatic system), he’s had a complete recovery and is living happily, with no viral-load, with his husband. He’s still choreographing and on faculty at The New School, where he is dance program director, and he teaches a course titled “Performance in the Age of Pandemic.”

- Christopher Pilafian was director of dance and vice chair of the Department of Theater and Dance at UC Santa Barbara and served as artistic director of the resident professional company, Santa Barbara Dance Theater. After retiring from UCSB in July 2021, he continues to paint and to contemplate making dances.

— + —

Historical Essays Leave a comment