Last fall, after we’d been cooped up with our screens for a year and a half, theaters started opening up. I sprang back into theater-going, happy to experience live dance again. There was nothing tentative or just-getting-back-into-it about these ventures, and much to get excited about. As always, this list is limited by what I was able to see. I organized this by categories rather than chronologically. (A short version of it appears in the Berlin-based Tanz magazine Yearbook.)

Premieres

Bill T. Jones’ Deep Blue Sea looms as an epic work. From the solitary figure of an aging man (Jones) in the vast space of the Park Avenue Armory, to the spectacular rendering of an engulfing sea (design by Elizabeth Diller and Peter Nigrini), to the literary references (Martin Luther King and Herman Melville), to the Bill T. Jones/Arnie Zane Company’s intricate groupings, plus about a hundred community participants swarming into the space, this work was overwhelming. It summoned the rage, sadness, and fierce clarity of resisting systemic racism.

For Ballet Hispanico at New York City Center, Annabelle Lopez Ochoa created Doña Perón, a full-length ballet about the short, tumultuous life of the first lady of 1940s Argentina. The corps embodied Evita’s passionate working-class supporters as they powered through striking choreography. The heroine’s most emotional moments tore through the silence between Peter Salem’s musical sections.

Compañía Nacional de Danza, now directed by Joaquin De Luz, received a warm welcome at the Joyce Theater. The company brought Johan Inger’s visually stunning Carmen, a tale about innocence vs. violence told from a child’s point of view. Dark, lurking (human) shadows crept around the doomed characters, suggesting that violence comes from within as well as from without.

Dance Theatre of Harlem brought an extended version of Balamouk, a rousing celebration, to City Center. The combination of Annabelle Lopez Ochoa’s choreography, the Klezmatics’ infectious beat, and Mark Zappone’s colorful non-binary costumes make for a festive piece. It felt like a village parade that everyone wanted to join.

In Cave, Hofesh Schechter’s new work for the Martha Graham Dance Company, also at City Center, the dancers threw themselves into wild club dancing. Their tribal, pulsating movements trod the line between joy and despair. The “creative producer” of this work was Daniil Simkin, a principal with both Staatsballett Berlin and American Ballet Theatre; he joined in their ecstatic gyrations, throwing in a few multiple pirouettes. (Good news: Cave will return to City Center for Fall for Dance.)

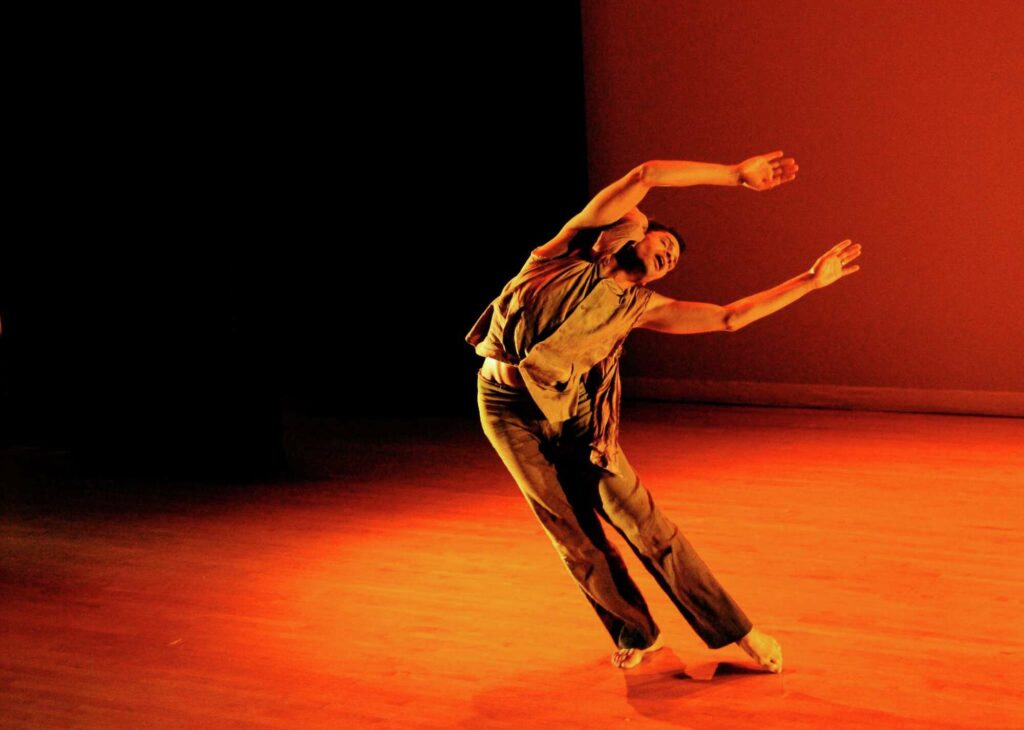

The Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater, also at City Center, had to shut down mid-season due to Covid. Luckily, they had already presented a program of works by artistic director Robert Battle—and it revealed how masterfully his choreography balances restraint and explosiveness. I was so taken with this program that I wrote about it here.

On a more intimate scale came Irish Modern Dance Theatre’s witty duet Cloud Study, choreographed by company director John Scott as part of La Mama Moves. Effervescent but infused with an ominous sense of danger, it seemed to be about searching and finding something different than what was expected. Both physical and metaphysical, it was danced and spoken by New Yorker Jamie Scott and Nigerian-Irish Mufutau Yusuf, two terrific contemporary dancers with a wondrous, subtle, spontaneous rapport.

From London, Candoco Dance Company brought their version of Trisha Brown’s masterful Set and Reset and Jeanine Durning’s improvisational Last Shelter to Brooklyn Academy of Music. Both pieces benefitted from the mix of differently abled bodies. Last Shelter sees the dancers applying Durning’s method of “nonstopping” to tasks like placing and replacing tables and chairs. A quality of rhythmic alertness made the choreography (improvising?) constantly engaging.

A jolt of astonishing body-slamming came from Abby Z and the New Utility to New York Live Arts. In Abby Zbikowski’s Radioactive Practice, six dancers thudded to the floor, sprang upward with no preparation, or whacked an arm to the ground, over and over. Like hard-driving athletes, they grunted and groaned with exertion. But this was no game. They seemed to be telling us that this kind of violence is what it will take to survive in these times.

At Jacob’s Pillow’s 90th-anniversary gala, we were treated to a kind of fantasy piece with two airborne figures from Kinetic Light. In There, Found, Here by Alice Sheppard in collaboration we Laurel Lawson, the two rose up high, somersaulted in the air, and swung across the upper space holding hands—all in wheelchairs. With gleaming lights in the darkness, the duet could have been titled Alice and Laurel in the Sky with Diamonds.

Pacific Northwest Ballet brought a refreshing program of contemporary ballet to Lincoln Center, sponsored by the Joyce. Crystal Pite’s Plot Point, with its faux plot (a street brawl? a murder? an adulterous affair? all of the above?) and creepy music from the movie Psycho, was spooky fun. Each character had a double, so the whole mimed drama was played out with simultaneous two-ness: human vs. robotic, real vs. unreal.

American Ballet Theatre premiered Single Eye, by Alonzo King (of LINES Ballet), at the Metropolitan Opera House. King’s sinuous style looked great on these dancers, pulling them into new territory: less frontal, more dimensional, more entwined with each other. Special mention: In a sublime oneness of dancer and choreography, Calvin Royal III held me rapt in his lithe, torqueing solo.

For the chamber company New York Theatre Ballet, Art Bridgman and Myrna Packer created a world of impressionist paintings come to life. Based on the famous French painter, Toulouse’s Dream was a dance-and-video mix in which Diana Byer, founder of the company, played the painter as though a Diaghilev type character. She wielded a wand like a paintbrush, activating all sorts of magical images.

Rennie Harris Puremovement’s LIFTED transformed the stage of the Joyce into a space of the Black church: a community of song and dance, love and forgiveness. The use of stopped action and backward action was arresting, so to speak. The choir (Alonzo Chadwick & Friends) filled the space with soaring voices. Special mention: Joshua Culbreath sped through astonishing break-dance spins and pretzel twists that were more than just tricks. His moves expressed the despair of his character, a lost orphan who wanted to be found. Sometimes an amazing head spin would end with a sudden splat on the back. For the audience, awe intermingled with sorrow.

Akram Khan’s Giselle for English National Ballet finally came to New York, performing at City Center. The setting was a dark, abandoned factory, represented by a huge grey wall that mysteriously disappeared and reappeared. The love duets were inventive, the ruling class costumes were outrageous, and the Wilis wielded long, threatening sticks. Special mention: Company director Tamara Rojo as a vulnerable Giselle, and then as a Wili, hovering on pointe, seemingly about to levitate into a spirit world.

Even before Liz Lerman’s Wicked Bodies started, we were all part of it. We were invited to write our own spells and post on an altar on the grounds of Jacob’s Pillow; we were asked what we were each the witch “of.” Lerman and her team created an environment complete with claps of thunder, a smoky stage for casting spells, and verbal explanations, e.g. why witches are associated with broomsticks. But it was the scene where King James tortures a woman to elicit a confession that stays in my mind. Each of the eight witch-dancers was totally individual, but most haunting of all was the dreamlike figure of the 80-something Martha Wittman wafting through the film (projection design by Olivia Sebesky); you could imagine her possessing the qualities that got women into trouble: wise, weary, and wielding magic.

At Japan Society, Yoshiko Chuma, impish yet masterful, led us through a sixties-style happening during the exhibit of Kazuko Miyamoto’s celestial sculptures. In Tipping Utopia Toward Kazuko Miyamoto, she communed with the art work, some of it made of thousands of strings. Clusters of people parted as Chuma glided, strode, or stomped through three galleries. The musicians, never in the same gallery at the same time, were double bassist Robert Black, violinist Jason Kao Hwang, and trombonist Christopher McIntyre. Chuma defiantly made mischief by pulling the double bass away from Black or sitting on the video monitor to cover the image of herself dancing almost 40 years ago.

Christopher Williams reimagined Les Sylphides as a queer reverie, and it was every bit as sensitive to Chopin as Fokine was in 1907. Special mention: In the role of the poet/dreamer, the vibrant Mac Twining twisted mid-leap and entwined lovingly with the sylphaderos.

Music at New York City Ballet

Two peak moments at New York City Ballet came from the music: The first was during the Stravinsky Festival when the orchestra rose up on a platform above the pit so we were almost face-to-face with the musicians. Andrew Litton conducted the Suite No. 2 for Small Orchestra, which has four parts: a fanfare-like march, a bird-chirping waltz, a giddy polka, and a loping gallop. This special occasion made one realize how rarely we see the people who make the music.

The second moment came with Justin Peck’s new Partita, with music by Caroline Shaw for Roomful of Teeth, who sang live. Verbal fragments burst into other-worldly chanting, and other sounds, including something I can only call a steam engine of exhales, whizzed by. I’d never heard anything like this as accompaniment for a ballet, and it seemed to bring Justin Peck into fresh rhythmic territory.

Site-Specific

Richard Move’s Herstory of the Universe at Governors’ Island portrayed, with a wild imagination, six goddesses from different eras in sites all over the island. It culminated with aerial dancer Lisa Giobbi, as Greek tree nymph Hamadryad, plunging between branches at Picnic Point.

The “In Plain Site” series of early Trisha Brown works came to Beach Sessions at Rockaway Beach, attracting a growing crowd of beach-goers. As I was standing on the shore line with the water lapping around my ankles, and watching the softly gestural Group Primary Accumulation, I felt a double dose of blissful sensuality.

Broadway, Roaring Back to Life

Some of the new musicals like Paradise Square, MJ the Musical, The Music Man, and for colored girls who have considered suicide/when the rainbow is enuf were bursting with dance. For dance history fans, Paradise Square’s depiction of the cross section of Irish and Africanist dance in the Five Points Neighborhood hit the spot. Choreography by Bill T. Jones with Garrett Coleman and Jason Oremus showed the gradual integration of Africanist dance forms with Irish stepping into what evolved into tap dance. Special mentions: Jared Grimes in Funny Girl, infusing astonishing steps with high-wattage energy; A. J. Shively in Paradise Square, buoyant and unstoppable as the Irish step dancer.

NYCB Divas as Curators

Tiler Peck’s program at City Center included an exhilarating in-person version of William Forsythe’s Barre Project, Blake Works II, the astounding physicality of Alonzo King’s duet Swift Arrow, and a sculptural group work by Peck herself. The evening was topped off by Time Spell, a giddy collaboration with tapper Michelle Dorrance and L.A. dancer Jillian Meyers, utilizing a pool of diverse dancers. Ballet and tap merged when Peck and Dorrance danced the same complex rhythms on a small, miked platform. Their high spirits made it sheer fun for the audience.

In “Dichotomous Being,” Taylor Stanley (who recently changed their pronouns) showed the deepening of a performer’s artistry. In a solo from Balanchine’s 1957 Square Dance, they were pristine in placement and feathery in the lightness of port de bras. The commission for Jodi Melnick, These Five, allowed subtle emotional connections to emerge through a sense of touch. Toward the end, Taylor faced the audience and gesticulated in some kind of hieroglyphics, as though daring us to read their inner life. The program concluded with Shamel Pitts’ Redness, a solo for Stanley of alternating explosiveness and soft openness. Special mention: Ashton Edwards in Andrea Miller’s Mango (a renamed section of her sky to hold for NYCB). With a delicate upper body and strong pointework, they had total abandon in the role that was originally Sara Mearns’. With their beguiling non-binary physicality, Edwards made Mango into quite a different romance.

Collectivity in Pandemic Times

Necessity is the mother of cooperation, and more groups are sharing resources now. Last summer, five major NYC companies— New York City Ballet, American Ballet Theatre, Dance Theatre of Harlem, Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater, and Ballet Hispanico—came together to meet, give support, and produce the BAAND Together series outdoors at Lincoln Center. This summer, they went a step farther and commissioned a piece that members of all five companies danced. That piece was the snazzy, jazzy One for All, to music by Funky Lowlives/Dizzy Gillespie, choreographed by Annabelle Lopez Ochoa, who devised the chic non-binary costumes herself.

Revivals — Gems of Dance History

In his program at the Pillow, Taylor Stanley gave a stirring rendition of Talley Beatty’s Mourner’s Bench (1948). In the opening move they seemed to melt upward. The dance was spare and taut, typical of the days of early modern dance when every movement was essential to the core idea. Not a single move was extraneous, all communicating so clearly the state of the performer. On the day I saw it, we were inside the Perles Studio, and just when Stanley was reaching out, thunder rocked the studio. Cosmic.

The Limón Dance Company performed Air for the G String (1928) by Doris Humphrey, restaged by Gail Corbin, at the Joyce. It’s a cool, stately dance, performed to cool, stately Bach music. But the saturated reddish environment (lighting reconstruction by Al Crawford) gave it a feeling of molten copper. Five women wearing long, draped gowns, glided in elegant groupings, sometimes opening like a flower.

Paul Taylor Dance Company went minimal with a selection of early works at the Joyce. In Events II (1957), two women just stand, takes steps, or squat, to the sound of the wind. A gentle breeze rippled through their dresses slightly. Perhaps one woman was waiting by a lamp post, perhaps the other was looking into a puddle. A poetic everyday-ness, performed by Eran Bugge and Jada Pearlman.

Dance (1979) by Lucinda Childs, with music by Philip Glass and film by Sol Lewitt, at the Joyce, proved once again that human bodies creating line, energy, and momentum can rise to the level of transcendence.

Not a choreographic gem, but a ritual gem: At Jacob’s Pillow’s 90th anniversary gala, people who’ve made the Pillow what it is, lined up onstage in a sort of parade of dance history. It started with Carmen de Lavallade, who first danced there in 1953, and Deborah Jowitt, who danced there in 1954. Many others were represented (Graham, Taylor, Cunningham, Pilobolus, etc), but those two great women were there in-person for us to show our gratitude.

Progress

Two strong women will soon be leading two of our greatest ballet companies. In the fall, Tamara Rojo, straight from her ten years at English National Ballet, takes the reins of San Francisco Ballet, replacing Helgi Tomasson after his thirty-seven years as director. Susan Jaffe, after leading Pittsburgh Ballet Theatre for two years, will become artistic director of ABT, which enjoyed thirty years with Kevin McKenzie at the helm. For Jaffe it will be a homecoming, as she was a principal dancer at ABT for two decades. Both Rojo and Jaffe have proven themselves as world class ballerinas as well as adventurous leaders. In these achievements, they match Wendy Whelan, who has been associate artistic director of New York City Ballet since 2019. Change is in the air.

¶¶¶

Featured 2