This year, instead of writing all the commentary myself, I’ve asked ten other dance writers to pitch in. Because each writer is spending more time with a particular book, each entry is more like a review than just a blurb. So what was meant as a quick gift guide has turned into quite an education. Big thanks to Mindy Aloff, Barbara Forbes, Ann Murphy, Lynn Colburn Shapiro, Robert Johnson, Bonnie Sue Stein, Marina Harss, Rosemary Novellino-Mearns, Morgan Griffin, and Emily Macel Theys.

La Nijinska: Choreographer of the Modern

La Nijinska: Choreographer of the Modern

By Lynn Garafola

Oxford University Press, 2022

Reviewed by Mindy Aloff

Bronislava Nijinska (1891–1972) was a choreographer, teacher, and coach whose impassioned belief in the principles of classical ballet, coupled with her obsession concerning the spiritual importance of high art, defined her. Trained in the Imperial School of the Maryinsky Theater, she joined Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes as a dancer and then, after a period of teaching and dancemaking mostly in Kiev, rejoined Diaghilev as a choreographer. From there, she went on to create an international repertory (nearly all of it eventually lost) for companies throughout Europe, in South America, and, finally, in the United States, where she, her second husband, and their daughter settled after World War II. Her legacy as a teacher, based in Los Angeles, included such stars-in-the-making as Allegra Kent, Cynthia Gregory, and Cyd Charisse.

Dancers tended to love her; however, Nijinska’s affiliation with the Soviet Union in the early 1920s, her particular brand of choreographic abstraction, her privileging of form and symbolic ideas over physical attractiveness for its own sake, her incorrigible temper, and the strangeness of the choreographic imagery in her work contributed to her controversial reception among critics and impresarios. When Frederick Ashton, her student in the 1930s, became artistic director of The Royal Ballet, he revived her two Ballets Russes masterpieces: the 1923 Les Noces (complete with full orchestra, chorus, and four grand pianos) and the 1924 Les Biches bringing her to London to oversee each production. Lincoln Kirstein included her Les Noces in his landmark history Movement & Metaphor, republished as Fifty Ballet Masterworks: From the 16th Century to the 20th Century. The Russian émigré critic André Levinson despised Nijinska—yet his daughter, who also became a critic, adored her.

This is a genius who led quite a life. Deeply immersed in her art, she still found time, among her ceaseless travels, to marry twice and give birth to two children (while, from her youth up to her death, nursing a quasi-religious devotion to her memory of the legendary bass opera singer Feodor Chaliapine, who had stirred her young girl’s imagination without physically requiting her crush).

Esteemed dance historian Lynn Garafola meticulously chronicles this life—in the first full Nijinska biography ever—across half the globe, in and out of four languages, through Revolution and two World Wars. Perhaps as a tribute to Nijinska’s constant battles to prove herself and be taken seriously in the company of male choreographers, Garafola also touches quite lightly on the achievements of Bronislava’s more famous brother, Vaslav Nijinsky, “God of the Dance.” Indeed, there is not even an entry for him in the book’s otherwise elaborate index.

Martha Graham: When Dance Became Modern, A Life

Martha Graham: When Dance Became Modern, A Life

By Neil Baldwin

Knopf

Reviewed by Wendy Perron

In the first pages, Baldwin situates Martha Graham (1894–1991) among great modernists like T. S. Eliot, Gertrude Stein, Picasso, and Frank Lloyd Wright. With massive research and a literary sensibility, this biography is as much about the era of American modernism as about a single dance artist.

The surprises in Graham’s life start at Santa Barbara High School. Martha was a voracious reader, talented writer, and basketball captain, setting a foundation for a life of both intellectual and physical challenge. She read throughout life, drawing inspiration from Nietzsche, Havelock Ellis, and Carl Jung for her choreography.

The account of Graham’s audition with Denishawn is delicious, with the grandiose Miss Ruth disdainful of the short, black-haired girl while Louis Horst at the piano murmured that she had something special. With the encouragement of Ted Shawn, Martha Graham sculpted herself into a dancer.

But she was determined to be more than an entertainer. Through constant experimentation, she strove to move beyond Isadora Duncan, “beyond ‘imperialism…and weakling exoticism.’” She traveled what Baldwin calls “the perilous journey through her inner landscape.” 201

The exterior part of that journey took her from Vaudeville to the concert stage. It was a gig at Greenwich Village Follies, (1923-25), where she danced alluringly in Michio Ito’s “The Garden of Kama,” that led to her teaching job at the Eastman School in Rochester. And it was her students at Eastman who formed her first company.

Baldwin is a storyteller. He skillfully builds suspense while recounting how Graham startled students with stillness at the Cornish School, how Erick Hawkins came into her life, and how she unknowingly — and haughtily—affronted Michel Fokine at a New School forum in 1931.

At 554 pages, this book keeps billowing out in different but related directions. Graham is always at the center — her conversations, happenstance meetings, evolving points of view, emergency rehearsals in the wee hours, plans with collaborators, and always, what she was reading. Along the way, we learn about other towering figures like Ted Shawn, Doris Humphrey, Mary Wigman, Michio Ito, José Limón, Helen Tamiris, Aaron Copland, Wassily Kandinsky, and Isamu Noguchi. With this wealth of information, what one reader might regard as a digression, another might find fascinating.

A definition of Graham’s modernism pops up during Baldwin’s description of Copland’s Piano Variations, which Graham used for her 1931 solo Dithyrambic: “This ‘straining-against-itself’ jagged advancement and retraction, favoring tightly woven, conflicting patterns, is quintessential Graham.”

Among the many dramatic utterings from the lips of Martha Graham is this one describing her dancing in the solo Frontier (1935), her first collaboration with Isamu Noguchi: she was “flinging myself against the sky.” To explain why Massine cast her as the Chosen One in his 1930 reconstruction of the Stravinsky’s Sacre du Printemps, she said it was her “passionate, destructive, ruthless quality…and also for a body that had animal strength.” 174

Although Baldwin focuses mostly on her modernist period (up till 1950), the book is expansive. The connections he makes between Graham and other modernist thinkers stretch what we know about her. Martha Graham was not only a great dance artist, but she was a major player in forging American modernism.

Sportin’ Life: John W. Bubbles, an American Classic

Sportin’ Life: John W. Bubbles, an American Classic

By Brian Harker

Oxford University Press

Reviewed by Wendy Perron

There are precious few films of John Bubbles available, but Brian Harker, in this epic biography, describes Bubbles’ dancing so vividly that we can practically see it and feel it. When Bubbles brought tapping back on its heels, he syncopated it, gave it irregular beats, and complicated the rhythms. According to Harker, he had “drop dead charisma” and a sexuality that was more threatening than that of the elegant, buoyant dancing of the more iconic Bill “Bojangles” Robinson.

Buck and Bubbles, the Vaudeville team that he was half of, was a sure-fire act. (Their given names were Ford Lee Washington and John Sublett.) As a piano and tap dancing duo that was also comedic, they would bring down the house. They toured with Carmen Jones and they performed in Gershwin’s opera Porgy and Bess. As Sportin’ Life, Bubbles had “just the right combination of attractiveness and evil,” according to one critic. His portrayal inspired Sammy Davis Jr. and Cab Calloway to follow in his footsteps for their interpretations of this role.

But the Vaudeville houses were yielding to movie palaces, and after Buck died, it was difficult for Bubbles to find work. Like Robinson, he was sometimes accused of being an Uncle Tom type of performer because of the limited roles available to him. But he enjoyed a comeback when television stars like Lucille Ball and Judy Garland hired him for their acts.

Harker, a music professor, brings to light Bubbles’ influence on jazz music. During the time when he haunts the Hoofers’ Club in Harlem, he is called a bridge between ragtime and jazz. (Btw, Jeni LeGon has said it was Bubbles who brought her into this sacred/profane cauldron of male dance creativity.)

Bubbles was known as the “father of rhythm tap.” He wasn’t a model human being (and who is anyway?) but he was a “genius onstage” who inspired many in the next generation, including the current dancer/actor André De Shields.

Mr. B: George Balanchine’s 20th Century

Mr. B: George Balanchine’s 20th Century

By Jennifer Homans

Penguin Random House

Reviewed by Mindy Aloff

Toward the end of this ardent and enthusiastically praised biography is an author’s note of several pages, explaining how deeply immersed in George Balanchine’s milieu she has been since her adolescence. She also enjoyed a close relationship as a student and a longstanding friend of Suzanne Farrell, the ballerina photographed with the master on the book’s dust jacket.

The Note adds that the author grew up in “an intense family of intellect and words” at The University of Chicago. The essentially wordless experience of dance—which Homans studied from childhood, including at the School of American Ballet, and performed as a professional dancer with several ballet companies outside New York—impelled her, finally, to plunge into much of the life of, and some of the works (e.g. Apollo, Concerto Barocco, The Four Temperaments) by George Balanchine. Her birth-to-death chronicle roams where the man roamed, with or without Lincoln Kirstein, the world-class impresario who brought Balanchine to America and who, Homans claims, maintained the longest continuing relationship that Balanchine had with any other person in his life. (Didn’t Balanchine and Alexandra Danilova meet when they were both kids at the Imperial Ballet School, in St. Petersburg?)

Homans’ academic field is history, and, admirably, she goes to some lengths to locate Balanchine’s life among political and cultural circumstances outside those of ballet. Even if dance isn’t your passion, there are other aspects of the 20th century here to keep your interest. The book offers up many passages of creative nonfiction concerning Balanchine’s personality and what he intended his ballets to mean, undergirded by research notes that run for nearly ninety pages. It also follows the choreographer’s medical and emotional sagas, offers unconventional readings of famous ballets, and continually takes the temperature of Balanchine’s sexuality and capacity for what Homans terms his “cruelty” to dancers.

Homans portrays Balanchine as intrinsically lonely, even in the midst of building an institution and a repertory in what is debatably the most social of the arts and despite his five marriages and numerous love affairs. Only Kirstein, constantly embroiled in institutional planning and fundraising—social activities if there ever were any—is presented as similarly lonely.

Mr. B will tell you what books Balanchine read, what kind of bedroom maneuvers he preferred, how the light-skinned African American company manager, the formidable Betty Cage, could pass for white. It talks about elements that went into Balanchine’s dances and, now and then, it shares information about technique. The story proper begins with the Big Bang revelation that Balanchine was illegitimate. What more could anyone want from a biography?

On Site: Methods for Site-Specific Performance Creation

On Site: Methods for Site-Specific Performance Creation

By Stephan Koplowitz

Oxford University Press

Reviewed by Ann Murphy

Choreographer Stephan Koplowitz, a familiar figure in the world of site-based performance, has been working in the genre for more than thirty years. His large-scale events, from Fenestrations at Grand Central Terminal (1987 and 1999) to the immersive site event The Northfield Experience (2018) in Minnesota, exemplify his interest in architectural scale, organized bodies in space and time, theater, media, history, metaphor, and a capacity for complex project creation and management.

Now, so does his new book, On Site: Methods for Site-Specific Performance Creation. In this comprehensive, wonderfully organized volume, he shares his extensive knowledge of a multi-faceted genre, and he does so with elegant logic, along with a spirit of generosity and care. This care extends to a wide array of “guests”—twenty-four fellow artists who also make work in non-traditional spaces and share their thoughts, creating a subtle, antiphonal rhythm throughout that makes the role of collaborators palpable.

On Site is no dry or abstruse tome. It’s an homage to performance in non-traditional spaces, and it’s a stunning template that takes the reader step-by-step through the processes. Koplowitz begins with site visits then moves to constructing structures, gathering partners, participants, public relations, money, budgets, tech, costumes, documentation, and, at the end, designing and making assessments.

From the outset, Koplowitz brings his colleagues and peers into the discourse. His first question, Why make site-specific work? is answered by Anne Hamburger, founder of En Garde Arts: “There’s something exhilarating when I’m outdoors producing a show and thinking, my stage is as high as the sky and as far as I can see….”

Next he asks, How do we start?, then moves on to How to make a master plan and organize research goals. Here, in the research phase, he underscores the centrality of knowing one’s site. The artist is no longer in the seemingly “blank” space of a theater. A site, regarded seriously, is at least in part an unknown, perhaps even a mystery, and by meeting, engaging, and learning about it, one opens oneself up to inspiration and transformation. The site becomes a partner, even in cases where the site incidentally—or accidentally—conditions a work, as in Merce Cunningham’s Events in a particular environment.

Koplowitz professes no utopian vision. His solidarity with fellow artists is earthy and muscular as he invites his peers to present ideas. (Generosity may be one of the 21st century’s more radical acts.) Also, he approaches even the daunting administrative elements of creating site-based work with a spirit of equanimity. He brings to it a reflexive engagement that encourages one to decenter themselves again and again to meet challenges with curiosity, engagement, compromise, and self-assessment.

It’s not a bad recipe for living.

Serenade: A Balanchine Story

Serenade: A Balanchine Story

By Toni Bentley

Penguin Random House

Reviewed by Barbara Forbes

The thrill of reading Toni Bentley’s moment-by-moment account of dancing Serenade, the first ballet George Balanchine choreographed in America, lies not simply in her meticulous description of the steps; nor in the fascinating story of how the dance came into being and earned its place in history; nor in learning why it was that Martha Graham wept when she first saw Serenade.

The reader is drawn in by the interweaving of all of the above with stories about the ballet’s creator and its composer, combined with portraits of the many artists who have contributed to the ballet’s evolution over time. Bentley is willing to delve deeply into her own intensely personal experience. It’s as if she is inviting us to dance with her in order to explore why this iconic ballet is one “of rapture, of crushing beauty.”

The opening paragraphs detail the rituals of preparation before the curtain goes up to reveal a formation of seventeen dancers on a bare, moonlit stage. Interpretation of the constant mood and scene changes during the ballet’s ensuing thirty-two minutes and forty-nine seconds is augmented by abundant historical information, yet anchored in the reality of the dance as it is happening, each step venerated and at the same time instructional.

For the reader who does not know the ballet, this book will no doubt promote the desire to see it. For someone already familiar with the wonder of Serenade, a sense of intimacy with its beauty will deepen. Perhaps an embodied description will bring to mind the Tchaikovsky passage for that particular moment of choreography. Balanchine claimed that he could see and hear better than anybody else: “God said to me, ‘That’s all you are going to have.’. . . I said, ‘Fine.’”

Bentley’s poetic impressions of Balanchine’s world support her belief, her conviction, that the Balanchine dancer’s unique passion is for “only one thing: to dance with him across the shadowed land of the eternal present.”

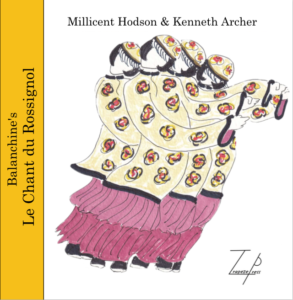

Balanchine’s Twenties

Balanchine’s Twenties

By Millicent Hodson and Kenneth Archer

Five small volumes—one each for Le Chant du Rossignol, Valse Triste, La Chatte, Le Bal, Cotillon—based on the authors’ historically informed theatrical realizations of the ballets with various companies in Europe and the United States.

Trapeze Press, a division of the Orion Group

Reviewed by Mindy Aloff

The ballets that George Balanchine made in Europe during his twenties, in the 1920s, are legendary for their glamorous contributors, exciting décors and musical scores, highfalutin audiences, mash-ups of fairytale elegance on the surface, and darkly suggestive subtexts. They also contain early examples of choreographic themes, images, and physical language that Balanchine himself put to use over the rest of his career. The authors here, dancer/reconstructor Millicent Hodson and the visual archivist Kenneth Archer, who have themselves excavated many supporting materials, are not intending to resurrect the ballets as alive and new, the way their original audiences perceived them. Still, their efforts at reconstruction—for both the page and the stage—let us glimpse the contour of the action, the floor plan of the choreography, the spectacle of the dancing bodies in costume, some of the choreographic imagery, and, here and there, impart an educated guess as to Balanchine’s intentions.

These “jewel” volumes—each a delightfully sized 7 x 7-inch square—conjoins the assembled elements into a kind of browser’s magick. They offer readable, contextual essays by Hodson and other scholars or performers; a “guide” to the ballet at hand that breaks down the dance action into comprehensible scenes; revealing quotations about the work from Balanchine’s contemporaries at the time of the premiere; footnotes and bibliography; and a wealth of meticulously arranged, relevant visual treasure seized from the past—in color or black-and-white, as appropriate to the source. Running through each volume are Hodson’s colorful drawings, derived from archival materials, that suggest how moments from the dances might have looked. The pleasure of the books is in no small measure owing to the layouts and design choices of Elizabeth Kiem, who runs Trapeze Press; however, the ultimate pleasure they give is owing to the editorial choices of Hodson and Archer and to their integrity in providing abundant evidence for their proposals of how the ballets lived on stage and why they remain haunting.

Ruth Page: The Woman in the Work

Ruth Page: The Woman in the Work

By Joellen A. Meglin

Oxford University Press

Reviewed by Lynn Colburn Shapiro

Ruth Page: The Woman in the Work begins as an academic pilgrimage into the late 19th- to mid 20th-century dance in Chicago through the lens of Page’s life and career. Eventually, this lengthy tome (429 jam-packed pages) blossoms into a delicious dive into the imagination and artistic journey of a gutsy innovator.

The book’s exhaustive detail across a wide range of inquiry demonstrates just how significant a force Ruth Page was. Like George Gershwin, with whom she collaborated, she combined classical and jazz forms into a style that was distinctly American. Page was determined to make dance relevant and accessible to a broader population, not just the elite few.

For a slew of reasons, not the least of which was her anchor in the Midwest, Page never received the recognition she deserved. Meglin’s book sets the record straight. As a 20th-century pioneer of theater dance, she collaborated with some of the greatest artists of her time, including Adolph Bolm, Frederic Franklin, Harald Kreutzberg, and Isamu Noguchi (with whom she had a love affair). She was extremely well-read and multi-talented as a musician, writer, and actress. She poured all this into her company, Chicago Opera Ballet, which was the resident ballet of Chicago’s Lyric Opera Company and toured independently under Columbia Artists Management during the early 1960s.

That she employed and choreographed for Black dancers, notably Katherine Dunham, when racial integration onstage was considered scandalous; that she developed themes in her ballets that tackled socially relevant subjects, sexuality, and controversial personalities; and that she had the daring to ridicule social norms, such as in Billy Sunday (1948), made her a stand-out among her peers. In 1938, under the auspices of the Works Progress Administration, Page and Bentley Stone created a feminist ballet, Frankie and Johnnie, inspired by the popular song.

Meglin offers the reader a visceral understanding of Page’s creative process. This includes casting, the dancers’ input, nuanced description of Page’s movement that defines character and relationship, and choreography that is insistently in service of storytelling.

Two of her colleagues, Bentley Stone and Walter Camryn, and after them, Dolores Lipinski and Larry Long, became the bedrock of ballet training in Chicago. Page’s legacy continues today through the Ruth Page Center for the Arts, which she founded as a ballet school and performance venue.

Meglin’s colorful depiction of Ruth Page’s determination includes detailing of obstacles she faced, such as financial restraints, public criticism of her daring use of sexually explicit themes, personality clashes, political in-fighting among artists, and racial integration on stage resulting in outrage in the press. Quotes from reviews throughout the 20th century give perspective on the evolution of aesthetics in the context of historic events, mores, and styles.

Page clearly had an impact on concert dance in America. Ruth Page: The Woman in the Work will inspire and inform ballet devotees, scholars, and practitioners who have the stamina to stay with it long enough to reap its rewards!

A Guide to Somatic Movement Practice: The Anatomy of Center

A Guide to Somatic Movement Practice: The Anatomy of Center

By Nancy Topf, with Hetty King

University Press of Florida

Reviewed by Barbara Forbes

Dancer, choreographer, and innovative somatic educator Nancy Topf had written the first draft of her book when she died in a plane crash in 1998. The manuscript, now lovingly re-worked by long-time student and colleague Hetty King, is a potent handbook for easeful, intelligent self-use. King learned from Topf how to embody thought, feeling, sensation, and intuition while moving. Along the way, she discovered that during her years of injurious dance training, “what had been left out was me.”

Topf agrees with psychologist James Hillman’s statement that “Consciousness has more to do with images than with will.” She uses conscious imagery to induce sensations that internalize anatomical principles of alignment. She guides us to imagine cycles of energy flowing along complementary lines of force. An attitude of kindness and curiosity invites reflection around a more nuanced perception of movement. “When I open a dialogue with my body,” says Topf, “I stop trying to manipulate it.”

She begins by introducing herself to her imaginary student “Italica,” the reader who will learn anatomical structure and function by applying meditative visualizations. Each element in their playful conversation is given an italicized voice with which to describe its role as a collaborator within the entire bodily system. For example, Clavicle says: “OK, Scapula, you are really my partner.” This uniquely personal process, based on Topf’s studies with somatic pioneer Barbara Clark, lies at the heart of her method, Topf Technique/Dynamic Anatomy.

So, too, does understanding the psoas muscle, which connects the legs to the spine. Topf offers practices for understanding deep developmental patterns so that we can experience the psoas as pathway, muscle, energy, structure, and also as a place of anti-gravitational upward thrust. We find grace and strength by visualizing the spine’s harmonious curves carrying our weight, one curve balancing upon the other with support from the flow of breath. We say “ ‘Yes’ to gravity’s force.”

For this reader, all discomfort from an old hip injury was relieved while walking and visualizing the relationship between psoas as suspension cables for the bridge of lumbar spine, and the crura muscles, which anchor the diaphragm to the lumbar spine, lengthening on exhalation. Thank you, Nancy Topf!

Diaghilev’s Empire: How the Ballets Russes Enthralled the World

Diaghilev’s Empire: How the Ballets Russes Enthralled the World

By Rupert Christiansen

Farrar, Straus and Giroux

Reviewed by Robert Johnson

More than an artistic director, Serge Diaghilev was a Prometheus. Early in the 20th century, his Ballets Russes set Europe ablaze and kindled a mania for ballet around the globe. Now dance writer Rupert Christiansen is carrying the torch in Diaghilev’s Empire: How the Ballets Russes Enthralled the World.

The author is a dogged researcher. To tell his story, Christiansen aggregates the latest scholarship, extracts tidbits from obscure memoirs, and rummages in the attic of Diaghilev biographer Richard Buckle. Christiansen’s judgments can be intemperate: In contrast with the Ballets Russes, he writes, the repertoire of Anna Pavlova’s company was “garbage.” He lapses into slang, telling us that Diaghilev wished to “cock a snook”—whatever that means—at his critics back home. Christiansen is also parochial in that tiresome British way, sneering at supposedly “obligatory” Russian hysterics. He remains consistently entertaining, however, and offers a detailed introduction to his subject that may excite a new generation of balletgoers.

Christiansen’s best bits derive from the research of Diaghilev biographer Sjeng Scheijen, who broke new ground in 2009, and from the observations of Diaghilev’s contemporaries. Diaghilev’s Empire profitably quotes Marie Rambert’s description of Nijinsky’s technique, and Léon Bakst’s remarks on color as a powerful element in design. On the other hand, Christiansen shows himself gullible when repeating accusations that Diaghilev sought only to shock the public, and that Diaghilev knew nothing about dancing. The evidence of the Ballets Russes repertoire, even when imperfectly performed, demolishes both those claims.

Like some dance specialists, Christiansen has a weak grasp of art history. Thus, he misses the way Symbolism and the trend toward abstraction influenced ballets from Fokine’s Petrouchka to Nijinska’s Les Noces and beyond. He ignores, for instance, the spiritual character of Les Noces, and the self-conscious theatricality that ties Nijinska’s Romeo and Juliet to early Ballets Russes aesthetics and to its novel, Surrealist milieu. Romeo was not an idle provocation.

It has become fashionable in the age of Jeff Koons to discuss the marketplace for modern art, rather than the principles and aims of modern artists. Yet one winces at the suggestion that the Ballets Russes was merely a “shop window” for the likes of Picasso. Diaghilev’s activities were never crassly commercial. He had an aristocrat’s contempt for money and died penniless, after vastly enriching the world.

A History of Butô

A History of Butô

By Bruce Baird

Oxford University Press

Reviewed by Bonnie Sue Stein

Note: Japanese names in the article are stated last name first, as Baird, a fluent Japanese speaker, has done in his book (e.g. Tanaka Min is more commonly known in the U.S. as Min Tanaka).

Butô has become one of the most influential dance forms of the 20th century, and Bruce Baird’s new book traces and confirms that history and influence.

Butô, the avant-garde dance form, originated in Japan with the first performance probably in 1959, with the two founders, Tatsumi Hijikata and Kazuo Ohno. The literal definition of the word butô is “dance step or stomp.” However the term now commonly refers to the entire form, originally called “ankoku butô,” or “dance of darkness.” It is also thought of as a reaction against Western influence in Japanese politics and culture that is purely Japanese in nature. Most of the butô dancers wear white body makeup and torn or messy clothing, and they might alter their body form with fabric and costume. But there is more to the form than that. The first time many Western critics saw butô, it was remarked that the bombing of Hiroshima and the resulting human deformities were a direct influence.

The movements in butô are mostly based on deeply inhaled and subconscious imagery, such as imagining a thousand ants crawling up your legs, or butterflies behind your eyelids. These imagistic prompts result in physical embodiments that may appear to the outside eye to be awkward, spastic, or out of control—like watching a body in space reacting to outside forces. However a butô dance score might be composed of hundreds of these images and be as carefully constructed as any formal ballet.

In an article for TDR in 1986, I wrote that butô artists work beyond self-imposed boundaries, passing through the gates of limitation into undiscovered territory. Whether their gestures are slow and deliberate as with Ashikawa Yoko, or wild and self-effacing as with Tanaka Min, the artists share a dedication to transformation. The strength of their commitment is an extension of the samurai, never-give-up spirit that is essentially Japanese.

With this new publication, scholar Bruce Baird makes an enormous contribution to the dance field, offering an in-depth study following the work of ten key dance artists. All of these artists have used the term butô and/or re-defined butô, moved on to other genres, or for some, dropped the term altogether as a conscious act to free themselves from a pigeonholed definition. In fact, Baird deftly acknowledges this troubled definition in the book’s conclusion. One example is Maro Akaji (b. 1943), the famed director/actor/dancer and spectacle genius of Dairakudakan (Great Camel Battleship). The company, celebrating its 50th anniversary this year, was the first butô seen in the U.S. at American Dance Festival in 1982. Though Maro keenly traverses dance and theater definitions. Dairakudakan’s early member, Amagatsu Ushio, went on to found Sankaijuku (School of Mountain and Sea), probably the most famous butô company worldwide.

Choosing some famous and some not so famous dancers, ranging from artists from Japan to those whose work developed outside Japan, Baird shows a number of facets of the dance form that might not have been exposed before. He eventually states that butô is beyond definition while continuing to be a major dance influence.

Baird’s book is a welcome historical resource and commentary. His knowledge and first-hand research highlight the expansive nature of butô’s place in the 21st century.

The Choreography of Everyday Life

The Choreography of Everyday Life

By Annie-B Parson

Verso Books

Reviewed by Morgan Griffin

A slim book at 96 pages, Annie-B Parson’s The Choreography of Everyday Life walks the reader through a winding trail of strung-together thoughts, metaphors, images, and daily occurrences. It’s on one hand deeply personal, and on the other hand applicable to many. Parson takes us on a journey of conversations, memories, questions, and observations that seem to make up one single day. These “acts of dailiness” carefully weave themselves around a conversation on The Odyssey, tying characters and moments in Homer’s tale to simple everyday experiences. The writing defies a linear narrative (as only a post-modern choreographer can), but recurring themes are roped together and circle back. Somehow everything makes sense, and all roads lead to dance and choreography: the dance of conversation, the dance of arriving at conclusions, the choreography of protests and celebrations, the collaboration of our two lungs, the small hand duet of letter-writing….everything for Parson becomes a stage.

Even the book itself is a careful choreography. The spacing, brackets, punctuation, and images denote pauses, pairings, emphases, and visual cues. Verbs grow muscles, and metaphors become great choreographic tools. And though Parson appears to be an avid fan of Trisha Brown’s rejection of fanfare, there remains a healthy dose of drama throughout.

A simple stroll down the sidewalk turns into a collective tempo agreement, laden with dramatic pauses and spatial considerations; political rallies are choreographic decisions of bodies in space; nouns are post-modern; Instagram is a “theater of images;” and the pandemic is perhaps the greatest collective dance of all time. Parsons demonstrates that, “We are space makers, we are natural choreographers as we craft our paths and proximities” through life.

And as I read this small but mighty book, I add my own choreography of underlines, asterisks, page creases, and arrows, creating my own emphases and moments in time that weren’t there before, all the while wondering if everyone else who is reading this is doing the same.

Making Broadway Dance

Making Broadway Dance

By Liza Gennaro

Oxford University Press

Reviewed by Rosemary Novellino-Mearns

Never take it for granted that the people onstage who are making your heart race have an easy job getting you, the audience, where they want you. As told in this richly researched yet entertaining book, the skill, training, and hard work that go into creating musical numbers for a Broadway show are mind bending.

Liza Gennaro has done an impressive job of research on the history of dance in Broadway musicals. The reader will get a full education on how it was and is done, with wins and failures. Gennaro delves not only into different choreographers’ specific styles but also the unique way they prepare to face the task. As the reader, you experience that first day of rehearsal when the choreographer has a group of dancers/actors waiting for them to be creative. You quickly realize the serious preparation necessary to handle all that is expected of the choreographer. The rehearsal studio is filled with different personalities that can get in the way, including those ever-expanding egos that can wreak havoc with every drop of sweat.

This book covers choreographers from the beginning of the Broadway musical to today’s innovative creators. The process of Agnes de Mille’s characterization of “The Postcard Girls” in Oklahoma! (1943) was spot on for a dream/nightmare ballet. These dance hall girls with a complete lack of emotion on their faces set the mood immediately. Twenty years later Bob Fosse used almost the same sense of detachment with his sexy taxi dancers in Sweet Charity’s “Big Spender.” Jerome Robbins searches for authenticity of the character and why they need to express themselves with dance. He uses the Stanislavsky method, expecting the dancers/actors to dig into themselves for this kind of motivation.

From the intensity of Michael Bennett’s A Chorus Line in the 1970s to the cleverness of Andy Blankenbuehler’s work on Hamilton, to current innovators like Sergio Trujillo and Camille A. Brown, theater and choreography are ever changing. Working with non-dancers presents its own challenge and—if you “get it right”—its own rewards. Steven Hoggett’s work on The Last Ship was powerful and organic, and done with actors, rather than trained dancers. (A Beautiful Noise, with choreography by Hoggett, is on Broadway now.)

I enjoyed some of the history about Liza’s father, Peter Gennaro, who I was lucky enough to work with as a dancer. The revelation that Jerome Robbins was not the sole choreographer of West Side Story should set the record straight. Peter’s huge contribution to the Sharks’ choreography, uncredited, will surprise and shock today’s generation. I, for one, am happy that Liza Gennaro and her brother, attorney Michael Gennaro, are correcting this erasure by insisting that all future productions give credit for Peter Gennaro.

For anyone who wants to know what it takes to make Broadway dances, read Making Broadway Dance.

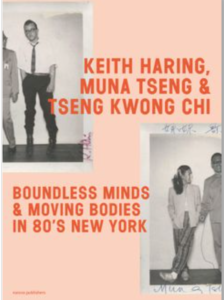

Keith Haring, Muna Tseng & Tseng Kwong Chi: Boundless Minds & Moving Bodies in 80’s New York

Keith Haring, Muna Tseng & Tseng Kwong Chi: Boundless Minds & Moving Bodies in 80’s New York

Schunk Museum

Nai010 publishers

Order at artbook.com

Reviewed by Wendy Perron

This book captures the wild and wooly East Village club scene of the 1980s, flourishing even while AIDS was devastating the arts. Previously defined categories were blurring, and Keith Haring was redefining graffiti as art. This book traces the connections between three artists who were crossing boundaries: Haring, choreographer Muna Tseng, and her brother, the photographer Tseng Kwong Chi. The only one of the three who survived the AIDS plague is Muna Tseng.

Muna had danced with Jean Erdman, and when she started making her own mythic stories, she collaborated with Haring. His drawings for Epochal Songs (1982), generously displayed in this book, are powerful, reflecting the horror of the nuclear arms race and other social ills—in an upbeat way. Together they invented a new piece of equipment: a special carousel that could travel while projecting the drawings. “We were so inventive,” Muna said, “because we had no money.” Her brother designed the compelling posters.

The following year Haring designed the sets for Bill T. Jones and Arnie Zane’s trippy Secret Pastures at Brooklyn Academy of Music, which upped the notoriety for all players. (For more on how Secret Pastures burst on the scene, see my essay on thirty-five years of the Next Wave Festival.) Jones and Haring had already collaborated on an iconic series of “Body Paintings.”

An existential quote from Keith Haring in the age of AIDS: “I can be made permanent by a camera.” That camera belonged to Tseng Kwong Chi, who documented Haring’s astounding creativity all over the city. Kwong Chi had his own surreal series called “East Meets West,” where he photographed himself in a variety of cryptic Chinese guises, complicating what it meant to be Asian American.

Somehow it’s fitting that in the midst of today’s pandemic, we would learn about artists of the ’80s club culture lost to us in the scourge of a former pandemic. In addition to the feast of visual images —street scenes, club scenes, Muna Tseng’s lovely dancing, Haring’s dynamic drawings — the book contains an interview with Muna plus essays by Bill T. Jones and Joshua Chambers-Letson. In this last, Chambers-Letson uses the word “queerness” to describe something larger than sexual preference, namely a social milieu “that is collectively produced on the margins of social, sexual, and aesthetic norms.”

During the ’80s and ’90s, it was wrenching to witness so many artists lost to AIDS. At the end of Bill T. Jones’ essay, “Thoughts/Recall,” he asks, “What Survives?” His answer: Relationship, memories and love of art.”

Red Star White Nights: The Life and Death of Yuri Soloviev

Red Star White Nights: The Life and Death of Yuri Soloviev

By Joel Lobenthal and Lisa Whitaker

Ballet Review Books

Available at Amazon

Reviewed by Marina Harss

Joel Lobenthal and Lisa Whitaker’s book Red Star White Nights is many things at once: biography and scrapbook, reminiscence and cultural history. Its central subject is the Soviet ballet dancer Yuri Soloviev (1940–1977), member of the Kirov Ballet (now known as the Mariinsky Ballet) and model to both Nureyev and Baryshnikov. Amongst his former colleagues and friends, as Lobenthal and Whitaker convincingly lay out, Soloviev was considered perhaps the greatest male classical dancer of his generation. In the West, where he was seen all too infrequently, he was overshadowed by flashier stars, like Nureyev, and by their headline-grabbing defections. Soloviev was the one who stayed, who persevered behind the Iron Curtain, dancing not only the classical repertory but idealized roles in Soviet ballets by Yuri Grigorovich, Leonid Yakobson, and Igor Belsky.

As history records, and Lobenthal and Whitaker describe in this deeply sympathetic portrait, Soloviev was also a tragic figure: isolated, “elusive,” depressed, sometimes exploited, and eventually “filled with despair.” During a particularly low period, when he was feeling underappreciated by the Kirov and at a loss about what would become of him after he stopped dancing, Soloviev left his home in St. Petersburg for a beloved dacha in the countryside and shot himself. He was only 37.

All suicides are an enigma, and Soloviev’s was no less so, but Lobenthal and Whitaker trace the depressing arc of the career of an artist of rare sincerity and vulnerability, utterly committed to his art and profession, and seemingly unable to shore up his defenses enough to survive in the harsh reality of the Soviet ballet world. Soloviev refused to join the Communist Party. Joining would have assured him greater access to foreign travel—and the fresh air, friendships, and new ideas that came with it—as well as better treatment by the ballet’s administration. And at the same time, he never considered defection, lacking the personal ambition and drive to take such a step.

The book derives depth from Whitaker’s friendship with Soloviev, the result of a brief but intense acquaintance that came about when Soloviev was on tour in Australia, Whitaker’s home at the time. Their touchingly sincere epistolary friendship is among the most revealing strands in the book, particularly a devastating letter dated 1969, in which he writes, “You must be able to understand how bad things are for me…everything has turned out so badly.” After that cry in the dark, she never heard from him again.

The final section of the book traces Whitaker’s efforts, after the fall of the Soviet Union, to connect with Soloviev’s friends and family and make some sense of his death. Red Star White Nights is built out of fifty-five short, sometimes very short chapters, exploring everything from Soloviev’s “personal style” to his partnering skills; his sexuality; his relationship with the leadership of the Kirov; Soviet “drambalet”; the Russian tendency to categorize dancers by physical type, or “emploi”; and the seismic effects caused by the defections of Baryshnikov and Nureyev. Lobenthal and Whitaker’s story is complemented by a huge number of photographs and documents. Its structure is sometimes choppy, but this is made up for by the impressive volume of material gathered and discussed. Red Star White Nights is clearly a labor of love.

Democracy Moving: Bill T. Jones Contemporary American Performance and the Racial Past

Democracy Moving: Bill T. Jones Contemporary American Performance and the Racial Past

By Ariel Nereson

University of Michigan Press

Reviewed by Wendy Perron

Taking the position that artists are public intellectuals, Ariel Nereson aims to “think with artists.” Bill T. Jones is indeed a public intellectual, and his work involves a lot of thinking and researching. An assistant professor of dance studies at the University of Buffalo, Nereson offers a multi-layered understanding of a particularly research-heavy stretch of Jones’ work, the Abraham Lincoln series. In this trilogy, made by the Bill T. Jones/Arnie Zane Company from 2008 to 2013, Jones set out to dismantle the simplistic reputation of Lincoln as the Great Emancipator. Nereson, in alignment with that goal, delves into America’s racial past that Lincoln was inevitably part of, educating us about Lincoln, Frederick Douglass, the Civil War, and Jones’ collaborative process.

Jones poses these questions at the outset: What does history mean to us? What does dance mean? What can dance do? One answer, for Jones, is that dance can thrust us into an unsettling quandary that pries open our understanding of history. He is so resistant to people’s assumptions—about Lincoln as well as about himself—that this trilogy, according to Nereson, emerges “excessive, opaque, ambivalent,” meaning nothing in this work is easily digestible.

Nereson points out that a concrete monument fixes history in time, whereas a dance is a more fluid way to commemorate a legacy. In the piece, Jones refers to Thomas Ball’s Reconstruction-era Freedmen’s Memorial (1876), which depicts Lincoln reaching down toward a kneeling enslaved man. Jones offers an alternative in two ways. First, he adds a kneeling woman, thus acknowledging that the first donation toward the statue was given by a freed woman. Second, through a choreographic sequence in which Paul Matteson, who represents Lincoln, not only reaches toward two Black people, but also touches their foreheads. He then he presses their heads downward, suggesting, in Nereso’s words, “persistent constraints on Black mobility.”

While Nereson’s effort to meet Jones where he stands as a challenging, uncompromising figure is laudable, she chases a veritable maze of theory that sometimes ties her into knots. Her objection to pure movement and postmodern dance as racialized is hard to take seriously when she cites Yvonne Rainer’s iconic Trio A as being full of repetition, when a hallmark of that solo is that it has zero repetition. So she seems to be making claims based on a piece she hasn’t even seen.

However the book is notable because it gives weight to an artist who interrogates our most cherished heroes and beliefs. Bill T. Jones’ life as a constantly questioning public intellectual is inseparable to his life as a constantly experimenting artist.

Milestones in Dance in the USA

Milestones in Dance in the USA

Edited by Elizabeth McPherson

Routledge

Reviewed by Wendy Perron

Dance historian Elizabeth McPherson has gathered ten essays that tell a complex lineage emphasizing BIPOC artists and social justice movements specifically in the United States. Reading this de-colonized dance history rooted in our home country can be revelatory.

In the first chapter Robin Prichard takes us through Native American dance, touching on the Hoop dance, the healing Jingle dress dance as well as pan-Indian identity. In Chapter 2, Dawn Lille gives an expansive view of ballet in this country, concluding with an eye to the future, especially in questioning gender roles in ballet. In the third chapter, on Black women in jazz and tap, Alesondra Christmas brings to the fore dancers like Alice Whitman, Josephine Baker, Jeni LeGon, Norma Miller, as well as current luminaries Debbie Allen, Dianne Walker, Dormeshia, and Chloe Arnold. In the next chapter, Julie Kerr-Berry applies a lens of gendered politics to historical figures like Duncan, St. Denis, Graham, Humphrey, Dunham, and Rainer. In Chapter 5 Miriam Giguere teases apart the differences between inspiration, borrowing and appropriation.

Hannah Kosstrin contributes Chapter 6, a kind of survey of dancing for social change. In addition to Anna Halprin, Jawole Willa Jo Zollar, Bill T. Jones, the late H.T. Chen, she brings in some less obvious choices. For example, have you ever heard of Anna Sokolow’s 1938 piece Filibuster, about the Senate’s resistance to passing an anti-lynching bill? In her discussion of the American Indian Movement, Kosstrin introduces in Daystar Rosalie Jones, a dancer/choreographer who draws on her Native heritage.

Joanna Dee Das challenges the supposedly opposite categories of art and entertainment in Chapter 7, revealing the racism inherent in the separation of high art and popular art. French-Cambodian dancer Emmanuèle Phuon contributes Chapter 8 on postmodern dance. She discusses not only Halprin, Judson Dance Theater, and Grand Union, but also the surrounding visual and theater arts that made that period, in her words, a “laboratory of rupture.” In Chapter 9, Carl Paris looks at the contested term “Black dance” and its relationship to postmodern dance. In his view, the latter includes Alvin Ailey and Eleo Pomare, as well as Rennie Harris, Thomas DeFrantz, and Ni’ja Whitson.

For the final chapter, Jody Sperling traces the lineage of dance-related technology from Loie Fuller’s magic lantern and Thomas Edison’s 1894 film of three Black men in a buck dance challenge to the ingenious ways that dance artists have utilized technology and media during the pandemic. Along this route, Sperling points out the invisibilization of Blacks on televisions and video games.

Each chapter challenges existing definitions, and each chapter concludes with suggestions for Further Reading. An extensive timeline at the end connects landmarks in U. S. History with what was happening in the national dance world. For those of us who teach dance history, there’s a bounty of inclusive information here.

Critique Is Creative: The Critical Response Process in Theory and Action

Critique Is Creative: The Critical Response Process in Theory and Action

By Liz Lerman & John Borstel

Wesleyan University Press

Reviewed by Emily Macel Theys

Liz Lerman, who founded Liz Lerman’s Dance Exchange (now simply Dance Exchange), started her long career by asking questions: Who gets to dance? Where is the dance happening? What is the dancing about? Why does it matter? Along the way, another set of questions got sparked: How to receive criticism for a work in progress without letting it derail the creative process? How to exchange feedback without making assumptions? In the 1990s, Lerman, along with John Borstel, formulated a process for giving feedback that has filled a need in the international dance world.

The new book, Critique is Creative: The Critical Response Process in Theory and Action, gives an overview of the process. The session often begins with an artist sharing a work that is at a point in the creative process where feedback can still help to shape it. The artist and viewers then gather in a circle for the four-step feedback process. Step one: Statements of Meaning; Step Two: Artist as Questioner; Step Three: Responders Ask Questions; and Step Four: Permissioned Opinions. This is a conversation among peers with a facilitator who gently guides responders back to the rules and agreements if they stray in their feedback.

Throughout the book, Lerman and Borstel share anecdotes of when the process has worked well (and hurdles they’ve experienced). They delve into CRP’s origin story, the ways it has evolved, and how it has helped both of them in their careers and lives. Then they widen the circle, inviting others into the conversation. Twenty-one artists, culture workers, educators, writers, and institutional partners share how they use Critical Response Process in their worlds. They include artists and alums from the Dance Exchange (where I am development director) like Elizabeth Johnson Levine, Gesel Mason, Bimbola Akinbola, Cassie Meador, as well as jazz musicians, playwrights, filmmakers, scholars, actors, poets, professors, scientists, and arts administrators. The essays cover topics like making dance work in communities, undoing racism, communicating better with teens, and applying the process across disciplines.

“Part of what makes it successful,” Lerman writes, “is its capacity to live with both rigorous hairsplitting orthodoxy and flexible structure that promotes a vigorous diversity of practice.” It can be applied to situations in and beyond the arts, and as a way of communicating through discord. (I use a less formal version of CRP at home when I’m helping my kids with their crafts or navigating challenging conversations with my spouse.)

Having worked with both Lerman and Borstel, I found great joy in learning more from them through their storytelling and seeing how far this process has stretched into corners of the world.

Ida Rubinstein: Revolutionary Dancer, Actress, and Impresario

Ida Rubinstein: Revolutionary Dancer, Actress, and Impresario

By Judith Chazin-Bennahum

SUNY Press

Reviewed by Wendy Perron

Why would Diaghilev choose a non-professional dancer for the lead in Fokine’s most sensational ballet—Schéhérazade? The answer is simple: Ida Rubinstein (1883–1960) had caused a sensation with her portrayal of Salomé in St. Petersburg. Sensual, alluring, and transgressive, she concluded her “Dance of the Seven Veils” in partial nudity. Always savvy about publicity, Diaghilev invited Rubinstein to join the Ballets Russes, which she did for its first two seasons. When she played Cléopâtre in 1909, a critic described her as “suffocating in her beauty, strange, enigmatic astonishing.” Adored by the public and fascinating to the intelligentsia, she was one of the most photographed, drawn, and written about women of the period.

Rubinstein was born into a wealthy Jewish family in Ukraine at the time of violent pogroms against Jewish communities. By the time she was 8, both parents had died of illness and she moved to St. Petersburg to live with an aunt. She often attended the Imperial ballet performances but was focused on acting.

Bennahum points out how Rubinstein blurred gender expectations in both her stage life— she occasionally played male roles—and her personal life—she became involved with “Paris-Lesbos.” This was part of her overall transgressiveness. It’s also part of what Bennahum calls “a stunning confidence in her body’s emotionality.”

During World War I, and again in World War II, Rubinstein turned her emotional, financial, and organizational resources to helping the war effort. She contributed ambulances, helped build hospitals, and spent time nursing wounded soldiers.

Rubinstein was a secular Jew who channeled her spirituality into art. “Art is truly a revelation,” she wrote. “Dance delivers us from heaviness, while music and poetry provide wings for our imagination.” She poured her money into the arts by forming her own company in 1928, commissioning choreographers like Fokine (who had choreographed her Salomé and had given her private lessons), Nijinska, and Jooss and composers like Stravinsky and Ravel, whose famous Bolero was written for Rubinstein. And always, her ally in the visual arts—Léon Bakst—who had created the first lavishly risqué costumes for her Salomé.

Rubinstein encountered plenty of anti-Semitism in the press. As a Jew in France in the late 1930s, she was vulnerable. But she stayed in Paris until May, 1941, when the Nazis were actually crossing the border into France. She flew to Algeria and made her way to London. All of her belongings in Paris were seized by the Nazis, which is why there are so few letters and other documents are available for research.

But Bennahum (with the help of previous research by Lynn Garafola) does a good job of reconstructing a life that contributed so much to the performing arts. Rubinstein had privilege in terms of money, beauty, and talent—none of which protected her from the steamroller of anti-Semitism.

Books received or announced

The Oxford Handbook of Hip Hop Dance Studies

Edited by Mary Fogarty and Imani Kai Johnson

Oxford University Press

Dark Matter in Breaking Cyphers: The Life of Africanist Aesthetics in Global Hip Hop

Imani Kai Johnson

Oxford University Press

Dance and Ethics: Moving Towards a More Humane Dance Culture

By Naomi M. Jackson

Intellect Books

An Empty Room: Imagining Butoh and the Social Body in Crisis

By Michael Sakamoto

Wesleyan University Press

Putting My Heels Down: A memoir of having a dream…and a day job

By Kara Tatelbaum

Motina Books