Embedded in Alexei Ratmansky’s ballets are history lessons for us. When watching American Ballet Theatre dance his Shostakovich Trilogy (2012), I saw a keen attention to shape, a gravitas in the surging masses, that reminded of Léonide Massine’s symphonic ballets. Massine was the top choreographer of the 1930s but is now all but forgotten. (More about Massine later.)

Sprinkling References to the Past

If you watch Ratmansky’s ballets closely, you’ll see images of previous ballets tucked into his choreography. In Pictures at an Exhibition, which he made for NYC Ballet last year, the first scene borrows the formation of the nine goons (drinking companions) of Balanchine’s Prodigal Son. And later the dancer in yellow, a role created by Wendy Whelan, quietly touches the floor. It calls to mind the end of Jerome Robbins’ Dances at a Gathering when the man in brown touches the floor, letting us feel that all the dancers are a community standing on one ground. Whelan also stoops to the floor in Ratmansky’s 2006 Russian Seasons, so that gesture was some kind of farewell to her on that stage. (By the way, in this clip Amar Ramasar, who is terrific in Pictures, talks about the choreographer’s impetus.)

Ratmansky’s Pictures at an Exhibition for NYCB with Gonzalo Garcia, homepage photo of Adrian Danchig-Waring and Wendy Whelan, photos by Paul Kolnik

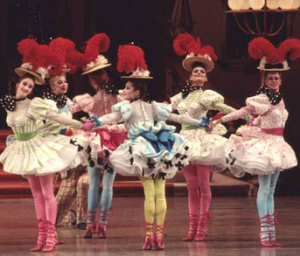

In Ratmansky’s Cinderella (2002), which the Mariinsky brought to BAM last month, there’s a moment in the first act when the stepmother and stepsisters, during their slapstick “dancing lesson,” land on the floor in the final position of Fokine’s Dying Swan. It’s only a split second but it prompted a chuckle to realize that these images are at the choreographer’s fingertips.

Did you ever look for the “Ninas” hidden in the drawings of theater caricaturist Al Hirschfeld? That’s a little what this has become for me. There are many reasons to see Ratmansky’s works more than once, but his version of “finding the Ninas” is definitely one of them.

Soviet Innovators

Ratmansky has not only quoted Balanchine, Fokine, and Robbins, but he’s made us aware of the pioneers of Soviet ballet like Gorsky, Vainonen, and Lopukhov. In my 2010 interview with Ratmansky, he mentions that he based his new Don Quixote for Dutch National Ballet on Alexander Gorsky’s version. Gorsky was the Bolshoi Ballet director who steered the company through the rocky Russian Revolution. Ratmansky’s remakes of Bolt and The Bright Stream pay tribute to Fyodor Lopukhov, one of the first great innovators of Soviet Ballet in St. Petersburg. And his recent staging of Flames of Paris honors Vasily Vainonen, whose 1934 Nutcracker is still performed by students at the Vaganova Ballet Academy. Until now, Flames of Paris was known to us only as a vehicle for pyrotechnics at galas.

Getting Back to Massine

Massine with Moira Shearer on the set of The Red Shoes, 1948

Massine made more than a hundred ballets for Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes and the companies that followed. He also danced in, and choreographed for, Hollywood movies. You’re most likely to know him as the Cobbler in The Red Shoes or the choreographer of Gaité Parisienne (1938). His symphonic ballets, starting with Les Présages in 1933, were a breakthrough.

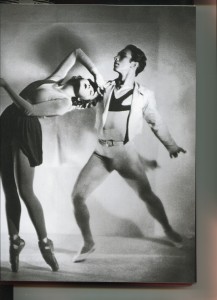

Irina Baronova with David Lichine in Les Présages (1933), sets and costumes by Andre Masson, photo by Studio Batlles

In the new book about Irina Baronova, the famous baby ballerina describes Les Présages, in which she played the role of Passion—at age 13. “It was a sensation when it opened in Monte Carlo and then Paris. Some musicians thought that it was a sacrilege to try and interpret a symphony that was a complete work of art in itself. The art world had never seen an abstract symbolist ballet set before, making no attempt to represent reality. The dance world was shocked by the modernity of the work coming from a classical ballet company. Les Présages immediately established Massine as an important choreographer.”

As I mentioned, Massine’s symphonic ballets surfaced for me when I saw certain pieces by Ratmansky. So I wasn’t surprised when I learned, at the Sundays on Broadway last week, that Ratmansky is an admirer of Massine ballets. Léonide Massine’s daughter Tatiana, who was the guest that night, told us that when Ratmansky was director of the Bolshoi Ballet, he presented an evening of three Massine works: Three-Cornered Hat, Les Présages, and Gaité Parisienne. In 2008, in The New York Times, Alastair Macaulay wrote, “I find it fascinating that at a time when it has become unusual to see a single Massine ballet anywhere, Mr. Ratmansky presented a Massine triple bill at the Bolshoi, thus bringing honor in Moscow to the most celebrated choreographer ever to come from that city.”

One can see the command of surging groups that was a signature of Massine’s symphonic ballets reflected in Ratmansky’s Snow Scene in his Nutcracker, Concerto DSCH (2008), and the Shostakovitch Trilogy (click here for a clip of San Francisco Ballet in this great work).

SFB in Shostakovich Trilogy by Ratmansky, photo by EricTomasson

This 1936 clip of the original Les Présages, shot in Australia when the Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo was on tour, shows how grounded, how focused on mass motion Massine’s symphonic ballets were. (Unfortunately you cannot hear the Tchaikovsky music.)

Massine’s Gaité Parisienne at ABT, photo by MIRA

There’s a bit of a warrior feeling, especially when the dancers shake their fists at the heavens. You can see why Michel Fokine, on seeing another one of Massine’s symphonic ballets, quipped, “Choreartium is Mary Wigman sur les pointes.” (Wigman was the counterpart to Martha Graham in Germany). This is the complex, earth-bound side of Massine, as opposed to the frothy, silly side displayed in Gaité Parisienne, which returns to ABT this spring.

And Back to Ratmansky

In a way, Ratmansky is a one-man peace branch between the U.S. and Russia. In a previous posting, I wrote, “Maybe, after bringing us The Bright Stream and On the Dnieper, Ratmansky has made it OK for the American ballet world to look back on Soviet times with something like curiosity rather than dread.”

We can thank Ratmansky for dipping our toes in that history. And while I’m at it, I want to thank Barnard’s Lynn Garafola for organizing an excellent symposium at Columbia University last week called Russian Movement Culture of the 1920s and 1930s. It revealed to me a wealth of experiments that mingled modern dance and ballet.

Featured Uncategorized 2