The “Radical Bodies” weekend at UC Santa Barbara turned out to be a profound experience for everyone involved. I am flooded with thoughts and feelings about the exhibit, performances, and conference. This was a momentous conclusion to a three-year project—and it’s not over. The exhibit comes to the NY Public Library for the Performing Arts on May 24 and will be up until September 16.

Yvonne Rainer, Anna Halprin, and Simone Forti come together at UCSB. All photos by Ellen Crane unless otherwise noted.

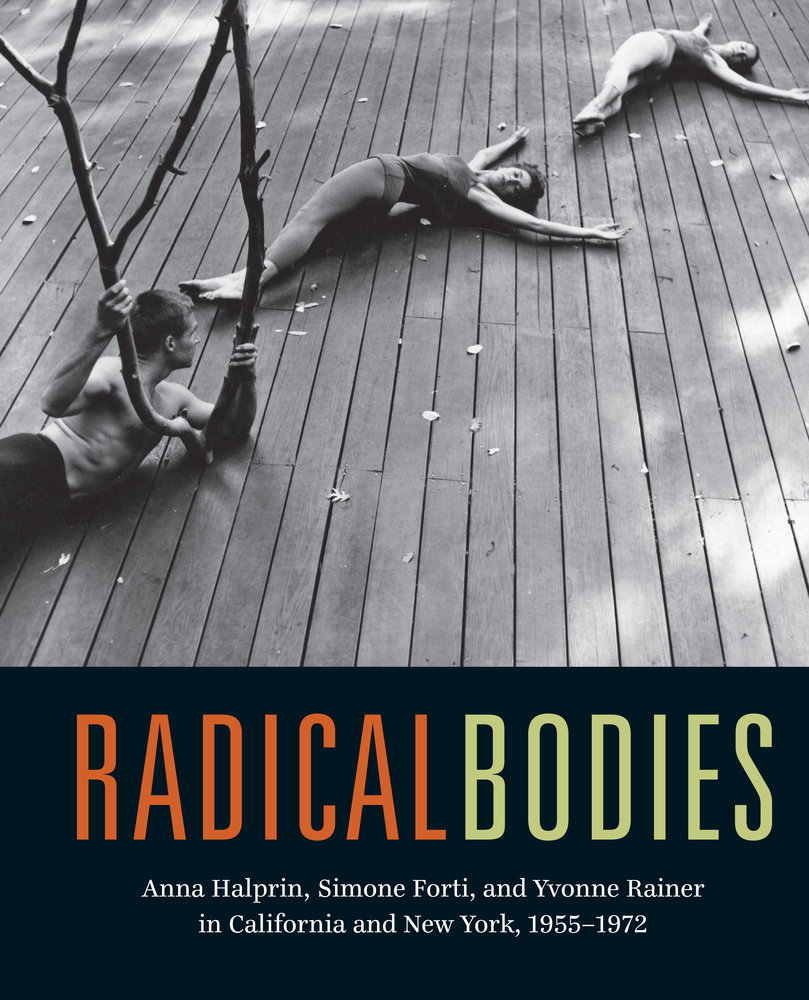

“Radical Bodies: Anna Halprin, Simone Forti, and Yvonne Rainer in California and New York, 1955–1972,” opened on January 27 at the Art, Design and Architecture Museum of UC Santa Barbara, kicked off by a full-day conference. The museum director, Bruce Robertson, is one of the curators; another is dance historian Ninotchka Bennahum, and the third is me. Bruce and Nina are both professors at UCSB and I was brought in because of my knowledge of the period.

The Exhibit

For me it was a revelation to realize, through our research, how much influence Anna Halprin had on Judson Dance Theater, widely known as the incubator of postmodern dance in the early 1960s. Her improvisations in nature, task dances, and use of scores—all these things were embraced by her student Simone Forti, who transported these ideas, contained—concealed?—in Forti’s own luscious dancing and dance-as-art concepts, to New York in 1960. Yvonne Rainer (along with Trisha Brown and Steve Paxton) was enthralled by Forti’s improvised dancing. Working on this project, I gained an appreciation of the sweep from West Coast to East Coast of some of these ideas.

The exhibit includes more than 150 photos, drawings, scores, and objects, plus rare footage of ’60s rehearsals and performances. Visitors can glean how each of the three dance artists redefined performance. The boldness of Halprin’s outdoor experiments, Forti’s affinity for animals in motion and her Zen-inflected drawings, and Rainer’s will to mess up the stage with boxes, mattresses, and human labor are all visible. Different styles of simplicity and different styles of defiance arise from these photos.

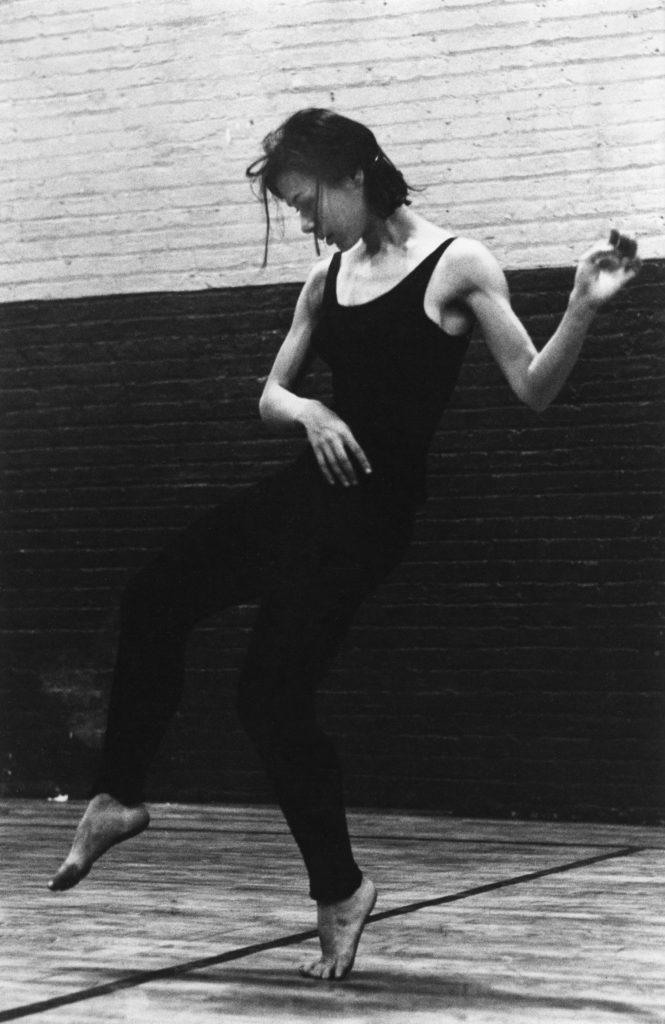

Yvonne Rainer in “Three Seascapes,” 1963 at Judson Church, photo © Al Giese, in the exhibit.

Anna, Simone, and Yvonne visited the UCSB dance department to prepare students to perform their work. Everyone was bristling with the awareness of this historic reunion. Some of the students said that this opportunity was the high point of their four years in college. After seeing the exhibit, Yvonne, who was famously influenced by Merce Cunningham and John Cage, said she never realized how much she had learned from Anna. We curators had been realizing the same thing—and how instrumental Simone was in intermingling Anna’s West Coast ideas with John Cage’s East Coast ideas. (Then again, Cage himself was from Los Angeles.) Actually, and uncannily, some of Halprin’s and Cage’s renegade ideas were very close, for instance, that art and life should be inseparable, and that everyday tasks have their own aesthetic and need no decoration.

I’ve been fascinated for decades with Judson Dance Theater. But when I embarked on the Bennington College Judson Project as a teacher 35 years ago (a project similar to “Radical Bodies” that included an exhibit, reconstructions, and a series of video interviews) I did not realize the huge influence of Anna Halprin. “Radical Bodies” balances out my former assumptions. It was Anna who immersed her students in improvisation, introduced speaking while dancing, and thrust the dancing body into natural and public spaces—very free-love, very California. When Simone came up with her breakthrough dance constructions in 1961, she was drawing on elements of both Halprin and Cage. (For more on Simone, see my essay on her in the Radical Bodies catalog/book co-published by UC Press.)

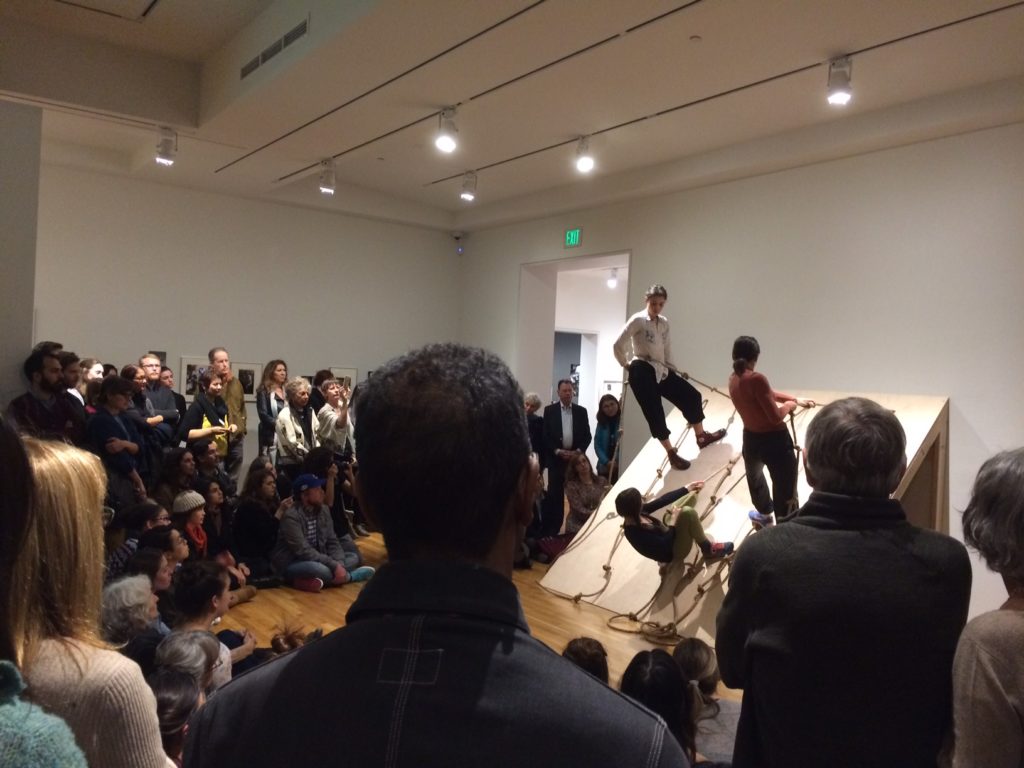

Students in Forti’s “Slant Board” at the opening of Radical Bodies exhibit, photo by WP

Judson in a Nutshell

In 1960 Robert Dunn, a disciple of John Cage, started teaching a course in choreography at the Merce Cunningham studio. His assignments were based on Cage’s notions of indeterminacy and chance. Among his first students were Simone Forti, Yvonne Rainer, and Steve Paxton. Not long after, Trisha Brown (along with Lucinda Childs, David Gordon, Rudy Perez and others) joined the class. Dunn was midwife to an explosion of experimental work that defied the rules of modern dance and became…postmodern dance. (To get an insight into Judson, read this article by Jack Anderson, written for The New York Times on the occasion of the Bennington reconstructions.)

However, “Improvisation was not on the grid in New York,” Trisha Brown observed. “Bob Dunn thought it was not acceptable as an answer to a compositional assignment.” (See page 32 in Susan Rosenberg’s new book, Trisha Brown: Choreography as Visual Art.) It was outside of class that Simone and Trisha got together to play. Or Simone and Yvonne and Nancy Meehan. Or Simone and Steve Paxton. When the exploratory improvisation à la Halprin came up against John Cage’s chance procedures as introduced by Bob Dunn, the encounter erupted into Judson Dance Theater.

Rainer’s “Concept of Dust: Continuous Project–Altered Annually,” with, left to right: Rainer, Patricia Hoffbauer, Pat Catterson, David Thomson, Keith Sabado (falling), and Emily Coates

The two nights of performances at UCSB included several works by Yvonne and her “Raindears,” a News Animation by Simone, and the students performing Chair Pillow by Yvonne and Anna’s Paper Dance from Parades and Changes. This last was utterly beautiful and deeply moving. (More about this later.)

The Conference

The daylong conference, conceived and organized by Ninotchka, began with a conversation between Anna, Simone, and Yvonne. I was over-the-moon happy to serve as moderator for these three extraordinary dance artists. I cannot give you the arc of the conversation, but I will say a few things I remember.

Talking about the 1960 workshop on Anna’s deck on Mt. Tamalpais, Simone recalled how very particular Anna was in guiding exploratory activity. The famous moment when Trisha Brown was sweeping the deck and suddenly thrust the broom out until she was almost flying in the air, stemmed from an assignment on momentum. (Again, see Susan Rosenberg’s book, page 23, to read the vivid memories of both Simone and Yvonne about Trisha’s low-flying episode. Also I’ve written about how this moment on the deck engendered many more instances of what I call Trisha’s Horizontal Dreaming.)

Anna, me, Yvonne at conference

When I asked each of them if they felt they were pre-feminist (since feminism didn’t surge until the 1970s), Yvonne allowed as how she and Simone had, over the years, an ongoing argument about this. Yvonne said she embraced feminism but didn’t feel she had the right to call herself that because she wasn’t an activist. Simone, on the other hand, said she did not feel drawn to feminism. Her father had told her she could be whatever she wanted, and her first husband, minimalist sculptor Robert Morris, had encouraged her and helped her become an artist.

Prompted by something in Simone’s poignant letters to Anna, 1960-61, which are published for the first time in our catalog/book, I asked whether ideas circulated differently on the West Coast and East Coast. I suggested that perhaps in New York artists were more concerned with “owning” ideas than people in California.

Prompted by something in Simone’s poignant letters to Anna, 1960-61, which are published for the first time in our catalog/book, I asked whether ideas circulated differently on the West Coast and East Coast. I suggested that perhaps in New York artists were more concerned with “owning” ideas than people in California.

Simone at conference

In response, Simone said she felt New York was more influenced by Duchamp and Europe, whereas California was more influenced by Suzuki and Zen. (This is a major insight that some scholar should follow up on.) And Anna blurted out, “I was annoyed. People from New York called me ‘touchy-feely,’ and what’s wrong with that?” Yvonne said something like, “That’s because Minimalism was against all that!” I pointed out that Anna’s sense of touch in dance—touching the earth, touching other bodies—infiltrated NYC via Simone, influencing Steve Paxton and Trisha Brown, and leading to Contact Improvisation.

My last question to our three graces was, What can an artist do in this new world disorder? Anna expressed outrage that the White House is now telling women what to do with our bodies. She also described her annual Planetary Dance, which originally led to the capture of a killer on Mt. Tamalpais. Simone said that in her News Animations she tries to bring in an awareness of politics. In her performance the next night, she made sly references to both Trump and Mussolini.

Simone in her “News Animation” at UCSB

In other conference presentations, Janice Ross, author of Anna Halprin: Experience as Dance, called Anna’s use of nudity “silent unpeeling.” She traced the use of nudity back to 19th-century Germany’s physical culture, and to Anna’s teacher, Margaret H’Doubler, who took her University of Wisconsin students to a lakeside where they danced nude. Scholar Peggy Phelan zeroed in on words, for example comparing Trump’s use of “move on her” in the infamous lewd sound bite from 2005 to a military sense of the phrase. “Moving on” as conquering, raping.

My co-curator Bruce Robertson juxtaposed Yvonne’s Parts of Some Sextets (1965) with the 1959 musical Once Upon a Mattress starring Carol Burnett. Although there were also scholarly nuggets about Rainer’s influence on the art world, it served as an apt prelude to Yvonne’s talk, “What’s So Funny? Laughter and Anger in the Time of the Assassins.” In this hilarious and scholarly lecture, her main point was “One person’s funny bone is another’s yawn.” In one part, Yvonne read, verbatim, a wondrously incoherent rant from Trump on his good genes. She concluded her lecture by showing, on video, the section of her dance Assisted Living (2012), in which Pat Catterson instigates a laughing fit that is seemingly uncontrollable and contagious. You can’t help but giggle when you see it.

Ralph Lemon, flanked by me and Ninotchka

Ralph Lemon’s presentation blew me away. In his talk, “Circling around post-modernism like weather,” he put our slice of dance history into context by saying how much he’s learned from the “white women” of modern dance. He started the talk by showing an archival video of Mary Wigman’s fierce 1913 Hexentanz, onto which he superimposed Carol Jones’ 1968 funk-soul song “Don’t Destroy Me.” The pairing was perfectly, uncannily synced, beat for beat. It was like he was saying, “This is how I locate myself in postmodern dance.” A brilliant juxtapositon. By labeling the lineage of modern-to-postmodern dance “white women,” he underscored the homogeneity of the early years of the genre. His first modern dance teacher was Nancy Hauser, who studied with Hanya Holm, the star student of Wigman who brought her technique to this country.

Wigman’s “Hexentanz”

How does Ralph, who was recently honored by President Obama with a National Medal of Arts, fit into this lineage? The answer is through his work with Hauser, then with Meredith Monk, then starting his own company with dancers who had studied the same somatic techniques that Trisha Brown relied on. But for Geography, his monumental, poetic trilogy that spanned ten years, he went searching for dance roots in Africa, Asia, and the American South, while keeping aspects of his unique blend of postmodern improvisation intact. His last work at Brooklyn Academy of Music, How Can You Stay in the House All Day and Not Go Anywhere? (2010) went so far beyond the decorum of concert dance in its physical and emotional exhaustion that it was its own No Manifesto—at least in my eyes.

After listening to Ralph’s Circling lecture and thinking back to his work of the last 20 years, this is what I realized: Ralph is taking postmodernism where it needs to go. It started as a formalistic stripping down to essentials at Judson Dance Theater in the ’60s; it opened up to complexity of movement and narrative in the ’80s and ’90s, and it has evolved to explore cultural and racial terrain.

And another thing: Hexentanz means “Witch Dance.” In some way, Halprin, Forti and Rainer are witches—the good kind of course. But also the kind that make people uneasy. Watching their performances at UCSB, it occurred to me that, had they been in Europe in the Middle Ages, they all might have been burned as witches. They all possess a certain divine madness. (See addendum* for Eva Yaa Asantewaa’s definition of witch.) Anna’s ability to create a healing kind of beauty out of something as mundane as paper; Simone’s luminous presence and slippery pathways between movement and words in her News Animations, and Yvonne’s refusal of performance conventions in Trio A, the screaming fit Three Seascapes, the droll humor and random readings in Concept of Dust: Continuous Project—Altered Annually, would have gotten them into trouble.

Patricia Hoffbauer in Rainer’s “Three Seascapes”

And one could say they put a spell on the students. We heard over and over how much the students were enchanted by working with them. (They had learned Simone’s dance constructions Huddle and Slant Board, Yvonne’s Chair Pillow, and Anna’s Paper Dance.) One said she wished Simone could be her grandma. Another who was taking Ninotchka’s course on Dance As Social Protest said she’s become obsessed with Halprin. Another said the experience changed her life. Many students as well as outsiders thronged to see the exhibit, which is up at UCSB’s AD&A Museum until April 30.

For me a heart-stopping moment came when Yvonne, in the middle of Concept of Dust (which I had seen twice before) suddenly cut loose and improvised an eccentric, top-speed, self-interrupting solo that thread through space. All I can say is, at 82, she’s still got it.

Yvonne rehearsing UCSB students in “Chair Pillow”

The Paper Dance

When the UCSB student dance company performed the Paper Dance from Halprin’s Parades and Changes (1965-67), we all realized this went way beyond an educational experience. The dance is an artistic experience that cuts across dance, sculpture, and the human condition. Anna dedicated this edition to North Dakota Pipe Line struggle.

In Anna’s ritual pacing, the 12 dancers entered from the back of the auditorium, walking and whistling. After making their way to the stage of the Hatlen Theater, they slowly removed their clothing while keeping their eyes fixed on a point of their choice. Once they started ripping up rolls of brown paper, we hardly noticed their nudity, so blended were their bodies with the shapes of the paper.

Anna Halprin’s “Paper Dance,” performed by UCSB students

The sound of the tearing, the melding of skin and paper, the floating quality of the paper wafting in air, all made a living sculpture of great beauty. Add to that the ceremonial quality, the sensitive timing of the group, the exquisite vulnerability of these young people exposing themselves—well, it made some of us cry.

They built to a climax of tossing shreds of paper high into the air with whoops of glee—from solemnity to exuberance in 12 minutes! Then they gathered up clumps of torn paper, held them close to their bodies almost like shields, and stepped downstage. Returning to the ritual pacing, they spread out in a long line, and—still holding the clusters close to themselves—they slowly bowed to us. We in the audience were stunned by the humble beauty of the whole sequence.

Students bowing in “Paper Dance”

Anna told me later that this was a symbolic bow, asking forgiveness of the Native American water protectors for destroying their environment. Brooke Smiley, the young woman who staged the Paper Dance, had just been at Standing Rock. She led the dancers through the rehearsal process, guided by her sense of responsibility of the body in the environment.

Stay tuned, because the Radical Bodies exhibit** comes to the New York Public Library for the Performing Arts at Lincoln Center from May 24 to September 16. We will have a slate of related events including the UCSB group repeating Paper Dance and Chair Pillow.

Curators Ninotchka Bennahum, me, and Bruce Robertson at reception for “Radical Bodies.”

Addenda

*Definition of witch, as given to me by dance writer extraordinaire, Eva Yaa Asantewaa: “A witch is someone grounded in ancient and worldwide philosophies and practices of connection to the forces of nature and Spirit, ways of being, thinking and relating that predate monotheistic religion and critique it. A witch is someone who loves and respects the power of forces outside of and within the self, someone capable of awe and instructed by it. Someone who works with all these ideas and energies through physical, mental and spiritual means, using physical or metaphysical tools and symbols. A witch might be trained in a tradition, a lineage, but is often self-identified, self-trained, self-directed and self-determined. There are many traditions and lineages—Celtic, Strega, Norse, Afro-Atlantic; old and tied to specific cultures or contemporary or hybrid. A witch is confident within a certain marginal, outsider status, can be skeptical, heretical, does not need the hierarchical structure or physical structures of patriarchal religion. Can acknowledge one or any number of god/desses or none at all, really. A witch is nobody’s cult member or slave. Is mobile and crafty. Makes, heals, blesses, nourishes, teaches, dances, sings, protects, speaks, challenges, celebrates.”

** Radical Bodies is organized by the Art, Design & Architecture Museum, UC Santa Barbara, and generous support is provided by the May and Samuel Rudin Family Foundation, Inc., the Ceil and Michael Pulitzer Foundation, the Metabolic Studio, and Jody Gottfried Arnhold.

We couldn’t resist: Here I am with old dance pal Wendy Rogers climbing the “Slant Board.” Photo by Linda Murray, Curator, Dance Division of NYPL for the Performing Arts

Featured 1