A young Syvilla Fort,1940 in Seattle, photo by Ernst Kassowitz, Courtesy Glory Van Scott.

A rare talent who danced with both Merce Cunningham and Katherine Dunham, Syvilla Fort was a leader as an educator. She was a force of nature, inspiring generations of students at both the Dunham School and her own school. She was a technical powerhouse in the Dunham style and one of the great teachers in New York. Writing in The New York Times, Jennifer Dunning called Fort “a choreographer and dance theorist of imagination and taste.” Alvin Ailey called her “our inspiration.”

Fort grew up in Seattle, Washington, the oldest of three children. From the age of three, she was bursting with the desire to dance—specifically ballet. Her mother took her to a number of ballet teachers in the area, all of whom abided by the racist practices of the day and turned her down. But several teachers agreed to give her private lessons, including Fred Christensen, the uncle of the more famous balletic brothers—Willam, Harold, and Lew. She was so avid about ballet that, at age 13, she gave free lessons to younger children in her neighborhood. She also performed in musical and dramatic productions in high school.

The Cornish School

In the early 1930s, Fort found a home for her love of dance at the Cornish School in Seattle. Her mother worked as a housekeeper for Nellie Cornish, who took an interest in her children and allowed Syvilla to enroll free of charge. Fort was one of three top students in Cornish’s modern dance program, which was under the leadership of former Graham dancer Bonnie Bird. One of the others was Mercier Cunningham (known as Merce only to his friends), and the third was Dorothy Herrmann, who soon left the dance field.

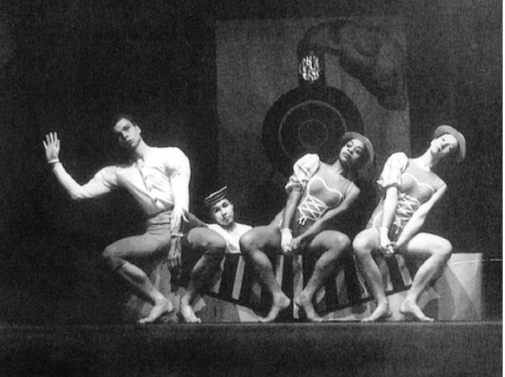

Bonnie Bird, Merce Cunningham, Syvilla Fort, and Dorothy Herrmann, in Three Inventories of Casey Jones, photo by Phyllis Dearborn, Courtesy the Cornish College of the Arts Archives.

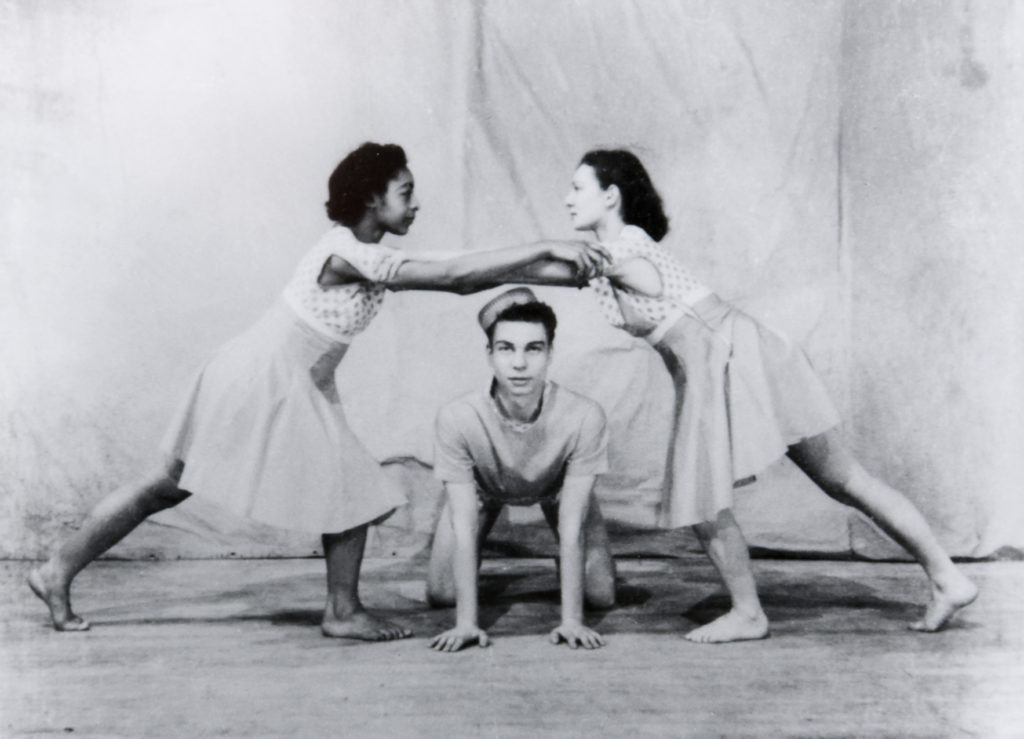

In 1939, the dance department produced an evening called “Hilarious Dance Concert.” Bird choreographed Three Inventories of Casey Jones for herself and the three favored students. Also on the program was Skinny Structures, a collaboration by the three students in which they played silly characters: Cunningham spoofed a bellhop that had been a popular figure in a cigarette ad, Fort did a take-off on “The Good Ship Lollipop,” and Herrmann played a kind of streetwalker. This work had premiered the previous year as a benefit for the cause of the Spanish Civil War. It was originally site-specific, occupying three “skinny” row houses on the campus.

Skinny Structures with Fort, Cunningham, and Herrmann, Courtesy Cornish College of the Arts Archives.

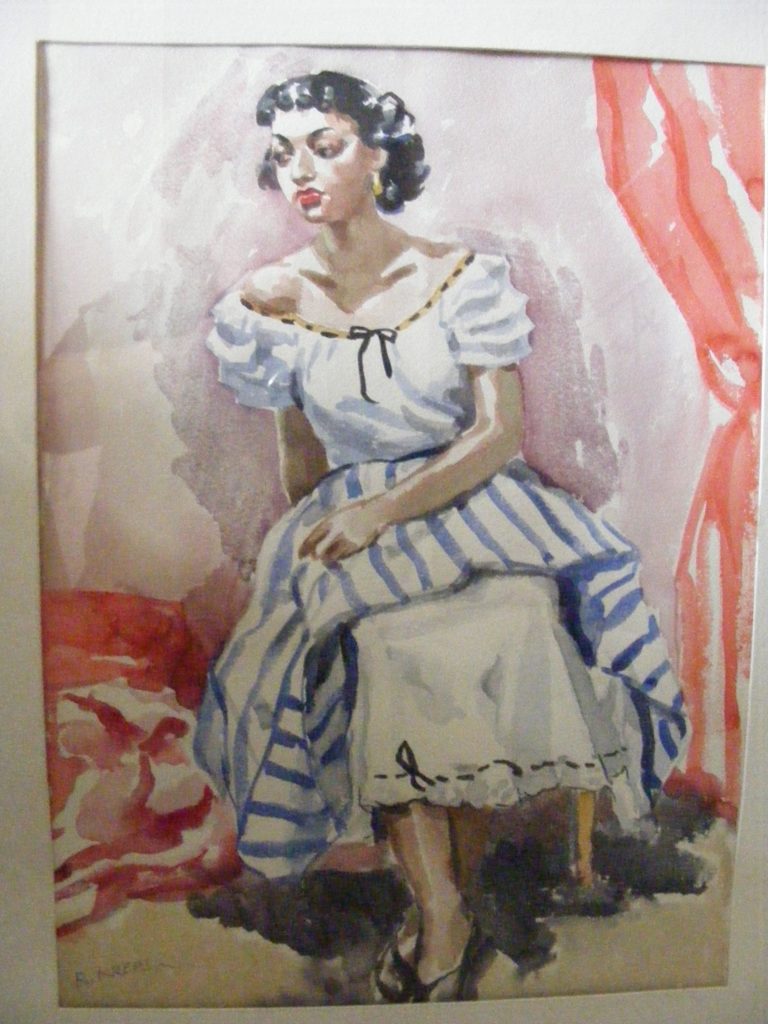

Another activity of Syvilla’s at that time was modeling for student artists. Below is a watercolor made by Ruth M. Kreps, who was part of a group of serious women artists, probably in 1936.

Watercolor by Ruth M. Kreps, Courtesy Glenn Airgood.

The Invention of the Prepared Piano

In 1938, Bonnie Bird hired John Cage as an accompanist, teacher of experimental music and choreography, and composer for dance works. For her piece Bacchanale (1940), Fort asked Cage to write something with an African “inflection.” Cage envisioned a percussion ensemble, but there wasn’t enough room in the Repertory Playhouse to accommodate. All he had was a piano. So he lifted the lid and stuck some screws and bolts and paper clips in between the strings. This was Cage’s first experiment with the “prepared piano.” Thus altered, it sounded like an entirely different instrument—sometimes reminiscent of a gamelan orchestra— and it’s one of the inventions Cage is known for. (The actual idea of altering the piano’s inner strings is attributed to Henry Cowell, but he did not develop it into a compositional element as Cage did.)

Making Training Available to All

After four productive years at Cornish (which did not become accredited as a college until 1986), Fort attended the University of Washington, where she earned her bachelor’s degree in two years.

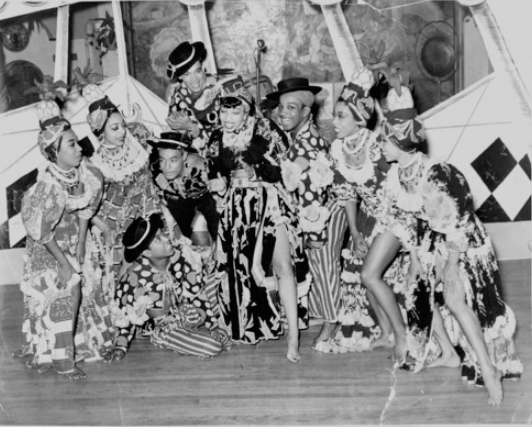

She moved to Harlem to dance with Katherine Dunham around 1941. According to Talley Beatty, she was “a very sensational dancer;” other sources say she received rave reviews. While touring to her home city in 1943, Fort was interviewed by the Seattle Times. She spoke out about the lack of opportunity for students of color: “A fight that a lot of young people have, especially if they are of a minority race, is to get the training they want.”

Dunham dancers: Lucille Ellis, Marie Bryant, Laverne French, Lavinia Williams, Claude Marchant, Roger Ohardieno, Tommy Gomez, and Syvilla Fort. Photo, Armand’s Photography, San Francisco.

She also expressed a dream that soon came true: “Through the Katherine Dunham group of dancers and other groups, things are happening. Maybe it will finally bring about a school or a place of training which would be open to all for artistic or cultural training.”

At the time of the article, the movie Stormy Weather—with Lena Horne, Bill Robinson, Cab Calloway, the Nicholas Brothers, and the Dunham troupe—had been shot but not yet released. Fort had this to say about the filming process: “It is much more difficult to sustain the mood when dancing before cameras than before an audience. When dancing before an audience they sort of ‘warm up’ to you and you to them at least before you’re halfway through the program.”

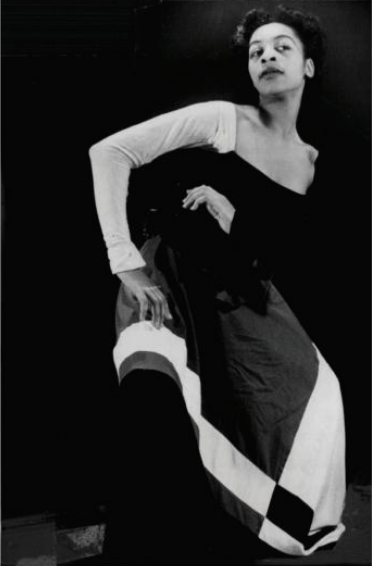

Fort in a Dunham work, photo by Carmine Schiavone, Joe Nash Collection.

Dunham opened the Katherine Dunham School of Dance and Theatre on West 43rd Street in 1945. Not only were there classes in Dunham technique, ballet, and modern dance, but also classes in percussion, dance notation, classic Spanish technique, dance history, acting (with master teachers like Herbert Berghof and Paula Strasberg), visual design, voice and speech, French, Spanish, music appreciation, psychology, and philosophy of religion. Writing in The New York Times in 1946, critic John Martin was clearly impressed with the range of offerings, the rigor of the pre-professional programs, and the inter-racial mix of the 400 students. But he also noted that it was financially precarious. Almost every student who wasn’t on the GI bill was on scholarship.

The Dunham school, however, made a huge impact. Dunham biographer Joanna Dee Das credits it with “desegregating the space of dance in New York and in promoting diaspora as a model for a peaceful postwar global order.” It was a central hub of many genres of dance. This is where Arthur Mitchell met the ballet teacher Karel Shook, years before the two formed Dance Theatre of Harlem.

When she wasn’t on tour, Fort taught both Dunham technique and ballet there. Two of her students, Marion Cuyjet and Sydney King, asked her to guest teach at their studios in Philadelphia. She did teach in Philly during the 1947–48 school year but stopped in 1948, when she took on the responsibilities of dance director of the Dunham school. That same year, her mother died, making her the legal guardian of her 8-year-old brother, John Dill (together, at right). He joined her in Harlem and eventually became a drummer.

When she wasn’t on tour, Fort taught both Dunham technique and ballet there. Two of her students, Marion Cuyjet and Sydney King, asked her to guest teach at their studios in Philadelphia. She did teach in Philly during the 1947–48 school year but stopped in 1948, when she took on the responsibilities of dance director of the Dunham school. That same year, her mother died, making her the legal guardian of her 8-year-old brother, John Dill (together, at right). He joined her in Harlem and eventually became a drummer.

The Phillips-Fort Studio of Theatre Dance

Although Fort was devoted to Dunham, she wanted to be independent. (Some sources say there was a falling out between the two women.) She had met tap dancer and war veteran Buddy Phillips at the Dunham school, and they married in the early 50s. In 1954, they opened their own school, which was to offer his style of Jazz Tap and her Dunham-based style of Modern-Afro, one block north of the Dunham school. Many students followed her to the new school, especially her children’s group, which included Walter Nicks, Julie Robinson (who later married Harry Belafonte) and Joan Peters. As with Dunham’s school, the Phillips-Fort Dance Studio offered a wide array of dance classes, adding tap classes led by Cholly Atkins, Honi Coles, and of course, Buddy Phillips.

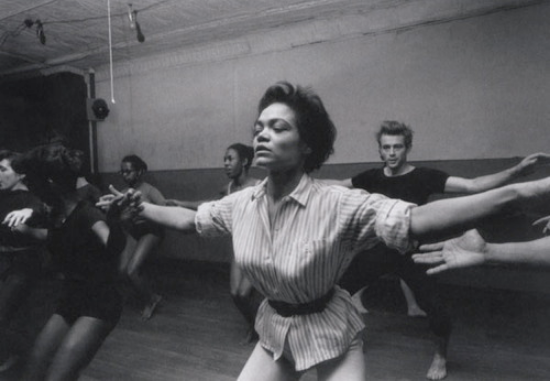

Eartha Kitt foreground, James Dean, background, most likely shot by Dennis Stock of Magnum photos.

Alvin Ailey, Chuck Davis, Eartha Kitt, Brenda Bufalino, and Yvonne Rainer all studied at the new school. So did James Dean, Marlon Brando, Eartha Kitt, Jane Fonda, Shirley MacLaine, James Earl Jones, and Geoffrey Holder. As current dance artist Katiti King said, “If you were an actor, she was the movement teacher to go to.”

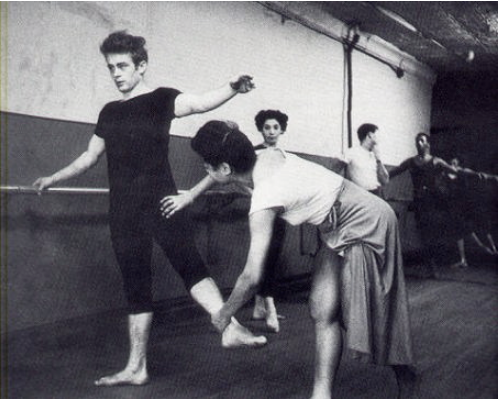

Fort correcting James Dean, most likely taken by Dennis Stock of Magnum photos.

Fort’s presence remains vivid in the minds of those who studied with her. Joan Peters, who has been chair for the Dunham technique at The Ailey School since 1978, was part of her special children’s group. “When you were around her, she gave you such a warm feeling,” Peters said recently. “There was a certain softness there so you were never afraid to try things in front of her.” As the children grew, more was expected of them. “She was more critical; she wanted you to be constantly thinking of what you were doing and not just sliding by.” This loving yet demanding approach created an incentive to do well. “You poured your heart out because you wanted her to be satisfied with what she saw.” And Peters had one more memory: “She had the most beautiful arms and hands, and we always tried to imitate that.”

Fort, 1940, photo by Ernst Kassowitz, Courtesy Cornish College of Arts.

Dr. Glory Van Scott, the triple-threat star who was invited to join New York City Ballet by Balanchine (she turned him down), devoted a chapter in her autobiography to Fort. Here is an excerpt:

There were times in her studio . . . when everyone was so synchronized, so spiritually in tune, that it seemed that the walls moved back and forth with us . . . Miss Fort plied her magic. We grew, we thrived, and went out to conquer Broadway, dance companies, and the concert world. We held Boule Blanches—white dress balls—talent showcases and performances at the Diplomat Hotel and other theatres in and out of town. We had a world where those who taught us cared, shared, and nurtured us—so much so that no matter where you were, you always returned to 153 West 44th Street to take classes and recount your travels . . . The studio was really home to us. . . Whenever Miss Fort walked into the room to teach class, there was an air of excitement and expectation, an almost holding-your-breath waiting to hear her say, “Good Afternoon, now let’s begin” . . . She had such beautiful, large, doe-shaped eyes—they seemed to mesmerize you into wanting to do everything right . . . When you said her name, it conjured up the feeling of comfort, of well being, of a mother’s quiet, steady, loving touch.

In a recent phone conversation, Van Scott recalled Fridays with special fervor:

On Fridays after classes ended at 7:00, we’d rush home and get ready for the Bambouche at 10:00. People would flood that studio, and you’d sign up on a list to show your work. Miss Fort and Buddy would both be there, and there was always food. There were kids of all languages. I remember Chinese acrobats wearing beautiful costumes. Sometimes we would dance until three in the morning.

When I asked Van Scott to describe Fort’s own dancing, she said, “She moved like a feather—light and flowing. When she danced her role in Danza, you’d be mesmerized. It was Spanish with a Moorish accent.”

In a completely different vein, Fort choreographed for Langston Hughes’s Prodigal Son in 1958, directed by Vinnette Carroll. Van Scott played the lead female role of Jezebel. “That was hot choreography!” she blurted out on the phone.

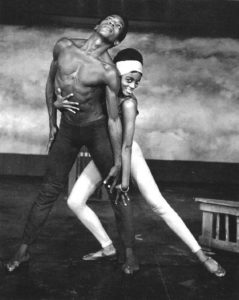

Langston Hughes’ Prodigal Son (1965) with Philip Stamps and Glory Van Scott, photo by Bert Andrews, Courtesy Van Scott.

Tap dance master Brenda Bufalino (and choreographer/director of The American Tap Dance Orchestra), also had a sense of uncontainable activity at the studio. “The studio was very small,” she told me, “and sometimes so crowded you felt like you might end up out in the street.”

Bufalino felt challenged and strengthened by the classes. “Syvilla gave a strong barre. Lots of hinging. You needed strong thighs and good knees. She really prepared you to dance. You felt ready to do whatever you needed to do.” Then Bufalino, who is 83 and still dancing, added, “which is what made me last so long.” The tapper also felt that Fort was sensitive to the fact that she was one of the few white dancers there. “Even when I was taking class with another teacher at the studio, like Talley Beatty or Walter Nicks, or ‘Chino,’ who taught Afro-Cuban, I felt she was watching over me.”

Children were captivated by Fort. Katiti King, who was a child when Fort died but whose parents shared the same artistic milieu as Fort, was also struck by her: “I remember her being kind, thoughtful, articulate, super intelligent. When she looked into your eyes, it didn’t matter your age or how you danced.”

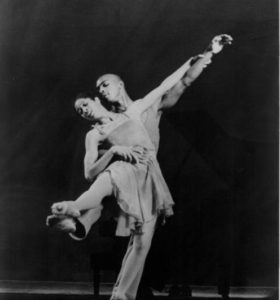

A tango with Peter Gennaro and Fort, likely taken by Dennis Stock of Magnum photos.

Buddy Phillips passed away in 1963. After paying for the funeral, according to her stepson, Sabur Abdul-Salaam, Fort was strapped. Luckily, just then Harry Belafonte recommended her for the position of helping develop a national dance company in the country of Guinea. She spent a few months there, giving the dancers a solid foundation in Dunham technique and other forms. According to Van Scott, she was so successful that the organizer in Guinea wanted to keep her longer. When returned, she resumed running her school. In 1967, she took an additional part-time job at Teacher’s College, Columbia University.

Because of the past discrimination she faced as a child, Fort was passionate about keeping her school open to everyone. “In the violent sixties,” wrote Van Scott, “she refused to bow to radical pressure to have only Blacks in her workshop group, for she felt that dance was universal.”

And yet she was committed to a Black dance aesthetic. As scholar Thomas F. DeFrantz has noted, Syvilla Fort was part of the sweep of African American artists aligned with the Black Power Movement, a precursor to Black Lives Matter. They recognized “the political need for a coherent ‘black aesthetic’ . . . outside traditional structures of dance performance.” These artists, who included Nanette Beardon, Chuck Davis, Louis Johnson, Joan Miller, Walter Nicks, Eleo Pomare, and Rod Rodgers, “sought to invest ‘black dance’ with the proclamation of self-representation, to use it as a tool . . . to create work relevant to African American audiences.”

A Starry Gala Tribute

Around 1974, this beloved teacher was diagnosed with breast cancer. As her strength faded, the Black Theatre Alliance produced a celebration of her life in 1975. Titled “Dance Genesis: Three Generations Salute Syvilla Fort,” it was held at the Majestic Theatre, where The Wiz was playing. Harry Belafonte and his wife Julie, a lead Dunham dancer who had trained under Fort, hosted.

In this clip from the Black Theatre Alliance, we see glamorous audience members singing her praises. James Baldwin, who was friends with Eleo Pomare and other dancers, said, “I’ve seen the results of her work, and she’s a very important woman.” Harry Belafonte said, “More silently, more tenaciously and more graciously than almost anybody else I know on the face of the earth, she made one of the most powerful contributions to the field of dance, to the field of theater.”

Tributes continued onstage that night. Alvin Ailey: “She is our mother, our inspiration . . . She taught us to develop a beautiful philosophy of how to live and how to love. She taught dance as a positive expression of the human spirit.” Dunham, who was in the hospital at the time, sent a message, calling Fort “one of the greatest people who ever honored the Dunham company with her presence.”

Dianne McIntyre’s Shadows, with Phillip Bond. Photo by Bert Andrews, Courtesy BAM Archives

The performances were stellar. Charles Moore performed Asadata Dafora’s classic Ostrich; Dyane Harvey danced what Don McDonagh of the New York Times called a “razor sharp” rendition of Pomare’s Roots; Chuck Davis’s troupe gave a rousing performance of the South African Boot Dance; Dianne McIntyre’s Sounds in Motion premiered Shadows, with music by Cecil Taylor. There were numbers by Peter Gennaro, who adored Miss Fort, and George Faison, the choreographer of The Wiz.

Fortunately, Miss Fort was feeling well enough to leave the hospital to come enjoy the evening with her friends and former students. Sadly, she left this world five days later.

After Her Passing

About a year after Fort’s death, Joan Peters resuscitated the Syvilla Fort Dance Company. It gradually morphed into the Joan Peters Dance Company. Van Scott produced the company’s programs of Fort’s works at Symphony Space in 1992 and ’93. Afro-Caribbean works like Yanvalou (1940), Rhumba (1954) and Carnival (1950), as well as Danza (1955) were staged. In 1992, Jennifer Dunning wrote that Danza “a delicately perfumed yet sturdy abstraction of the stylized Spanish “school” of dance. . . was performed to the hilt by Dr. Scott, Hope Clarke and Loretta Abbott.” In a 1993 New York Times review, Jack Anderson wrote that “What made Yanvalou (1940) striking was the way the cast conveyed a sense of communal solidarity and awe in the presence of divine powers.”

Glory Van Scott in Danza, 1992 Carmine Schiavone, Courtesy Van Scott.

Community builder, dynamic dancer, intriguing choreographer, beloved teacher, Syvilla Fort was lionized by the Black community. In a 1979 article in The Black Scholar, Ntozake Shange grouped her along with superstars Fats Waller, Eubie Blake, Charlie Parker and Katherine Dunham as the giants who “moved the world outta their way” and made art that reflected their lives.

Lastly, some good news: First: the documentary Syvilla: They Dance to Her Drum, made by notable filmmaker Ayoka Chenzira in 1979, is being digitized by the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences (timeline unknown). Second: Glory Van Scott and Joan Peters plan to mount some of Syvilla’s work next year (or whenever possible) at Symphony Space. Van Scott will produce and direct, and Peters will stage the dances. Maybe I’ll see you there.

Portrait of Fort, 1940s, by Carmine Schiavone, Joe Nash Collection

¶¶¶

Special thanks to Dr. Glory Van Scott, Joan Peters, Katiti King, Lee Gretenstein, Brenda Bufalino, Ayoka Chenzira, Glenn Airgood, and Bridget Nowlin, Director of Library Services, Cornish College of the Arts.

Other sources:

- Glory: A Life Among Legends, A memoir by Dr. Glory Van Scott

- Dancing Many Drums: Excavations in African American Dance, ed. by Thomas F. DeFrantz

- Dance in Review, by Jack Anderson

- Review/Dance: Tribute to a Choreographer, by Jennifer Dunning

- “Dance Genesis: Celebrating the Life and Legacy of Syvilla Fort“, by Reba Weatherford

- “Syvilla Fort, A Teacher of Dance,” by Amanda Smith, Dance Magazine, January 1976

- “Better Race Relationships Hoped by Seattle Dancer,” Seattle Times, April 16, 1943, collected in Kaiso! Writings by and about Katherine Dunham, eds. Vèvè A. Clark and Sara E. Johnson, p. 251

- The Black Tradition in American Dance, by Richard A. Long, photographs selected and annotated by Joe Nash

- “Bonnie Bird & Company,” by Maximilian Bocek, Cornish Magazine, January 2016

- Katherine Dunham: Dance and the African Diaspora by Joanna Dee Das

- “Syvilla Fort, My Sister, My Mom,” by John Dill, Tumblr page

- “Talley Beatty: Speaking of Dance,” directed and produced by Douglas Rosenberg, Charles L. Reinhart, and Stephanie Reinhart. American Dance Festival, 1993. Alexander Street, https://0-video-alexanderstreet-

- Video clip of Syvilla Fort BTA Tribute

- ” Syvilla Fort, a Dance Teacher Who Inspired Blacks, Is Dead,” New York Times, 1975

- The Selected Letters of John Cage, ed. Laura Kuhn

-

“The Legacy of Black Philadelphia’s Dance Institutions and the Educators Who Built the Tradition,” by Melanye White-Dixon, in Dance Research Journal, Vol. 23, No. 1 (Spring, 1991), pp. 25-30

Unsung Heroes of Dance History 16