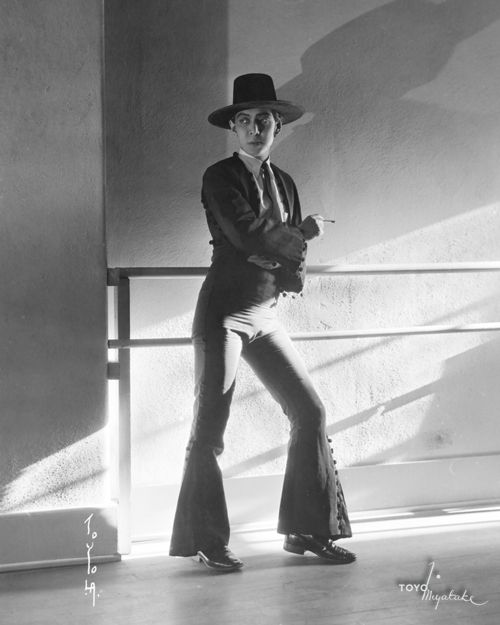

Portrait of Michio Ito, photo Toyo Miyatake Studio

Could it be that one of the pioneers of American modern dance was not American?

Japanese-born choreographer Michio Ito developed a distinctive, modernist vocabulary in the early part of the 20th century. From intimate, poetic solos in New York City to vast spectacles at the Hollywood Bowl, his choreography was grounded in a strong connection between music and movement. His works combined elements of East and West, and he influenced major figures like Martha Graham and Lester Horton.

He was called “one of the modern dance pioneers” by Ted Shawn (Caldwell 1994, 77). Pauline Koner, a prominent modern dancer in the 1940s and ’50s, went further: She called Ito’s work “the first modern dance” (Koner “On Dance”). A true citizen of the world, he inspired poets in London and mobilized the Japanese immigrant community in Los Angeles. In hundreds of works, he balanced East and West in search of a universal art—until he was arrested as an enemy alien after the bombing of Pearl Harbor in 1941. He disappeared from American view and disappeared from our dance history. As choreographer Dana Tai Soon Burgess asks, “How could Michio Ito’s legacy be wiped out so quickly?”

I am not suggesting that Ito choreographed masterpieces that have been tragically lost and should be reconstructed. I suspect his influence was more as a teacher and thinker than as a dance maker. But his short solos and his whole training system were foundational to the development of modern dance. Ito remains a fascinating figure, a lightning rod for current as well as past issues. Thankfully, the research continues to swell, carried out by scholars like Mary-Jean Cowell, Carrie Preston, Yutian Wong, Kevin Riordan, and Tara Rodman.

Early Life

Born in Tokyo to an art-loving, Westward-looking family, Ito studied piano and voice when he was young. His father, who studied architecture in the States, was influenced by Frank Lloyd Wright. The family was among those who were beginning to look upon Japanese and European culture as co-existing rather than warring (Rodman 17). At the age of 18, Ito left for Paris to study opera. But after seeing Nijinsky in Paris and Isadora Duncan in Berlin, he dropped vocal lessons and enrolled in the Dalcroze Institute in Hellerau, outside of Dresden. Just then the school was becoming a center for European modernism. There, as the only Asian out of 300 students, Ito learned Emile Jaques-Dalcroze’s method of integrating music and dance through arm gestures and walking patterns.

Exhibition of Eurhythmic dance, Hellerau Institute

The Dalcroze Institute offered more than a method. It represented a philosophy, a belief, an experimental approach to performance. Solos were emphasized as a mode of self-expression (Preston 9). The Hellerau Festival was the realization of the avant-garde ideas of theater director Adolphe Appia, who had designed for Wagner’s operas (hellerau.org). When Appia oversaw the design of the new theater for the Hellerau Festival, it was regarded, according to the Hellerau website, as “a visionary alternative” to conventional theaters. The Festspielhaus had flexible seating and different levels of platforms, “making it a ‘cathedral of the future’ (Appia) in which the audience and performers were supposed to merge into spiritual and sensory unity” (Hellerau.org).

From Appia, Ito learned about total theater and how both movement and lights could be unifying elements. In the summer of 1913, a radical performance of Orpheus and Eurydice attracted an audience of 5,000, including well known artists such as George Bernard Shaw, Oskar Kokoschka, Max Reinhardt, Rainer Maria Rilke—and the teenage Michio Ito (Hellerau.org and Cowell email).

A note about Hellerau and modern dance: Mary Wigman, who was to become the German counterpart to Martha Graham, had studied at Hellerau and later taught the Dalcroze Eurythmics in her school in Dresden. Thus Dalcroze was an underpinning for what became the German Expressionist dance, or Ausdruckstanz (Soares 45).

London society

When World War I broke out in 1914, the international students fled Germany and Ito went to London. As the story goes, just when he was down and out, he got invited to a soiree at the home of Lady Ottoline Morrell, where he was asked to dance. Being penniless, he had no proper costume, so the hostess loaned him an elaborate outfit she had on hand— and voilà, he performed so brilliantly that the guests begged him for more.

One might think he improvised, but everything Ito ever performed was planned at least to some degree. For this performance he danced a piece to Chopin that he had composed for his Dalcroze exam (Caldwell 40). As Lady Ottoline recalled about a number of these social events, “He would ask Philip [her pianist husband] to play a tune through, then think about it for a few minutes, and then start his interpretation of it, wild and imaginative, with intense passion and form” (Caldwell 42).

By the time of his debut on May 15 in a shared program at the Coliseum Theatre, an ad heralded, “The Famous Male dancer Michio Itow who has created a furore in Society with his repertoire of Harmonized Europo-Japanese Dances” (sic) (Caldwell 37).

He had mixed feelings about being labeled Japanese, as one can see in this passage:

Because I was billed as ‘The Japanese Dancer’ I had to create a ‘Japanese’ atmosphere. All my dances were original however. I danced a programme based on Shojo [the spirit of wine] and Kitsune [a folk tale about a fox] and sometimes even wore eboshi [formal black hat] and nagabakama [a long, pleated split skirt] as well (Preston 11).

His debut was called “novel and impressive” by The Times of London (Caldwell 37), and the appearance led to other invitations. But the pressure to appear Japanese followed him everywhere. Orientalism had been rampant in London since the 1880s (Sato 28). As Mary-Jean Cowell points out, the perception of Asian people was two-sided: “The image of the Oriental as a being of profound spirituality and artistic refinement coexisted with the devious, lazy and sensual stereotype” (Cowell 2001, 11).

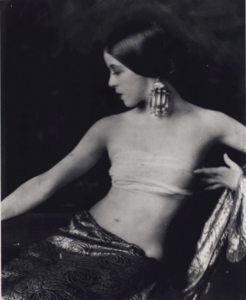

Yamada Tone Poem II 1926

Collaborating with Yeats

Ito started frequenting the Café Royal, an international hangout where his lack of English wasn’t a hindrance since he could speak German and French. There he met Ezra Pound and other artists (Caldwell 39). Pound was working on a translation based on Noh theater, and he’d asked the poet William Butler Yeats for help. They drew Ito into their project, even though he had an aversion to Noh, saying, “Noh is the damnedest thing in this world” (Caldwell 44). But he had absorbed enough of his own cultural roots to contribute something authentic. Yeats then decided to write a play in the Noh style—starring Michio Ito.

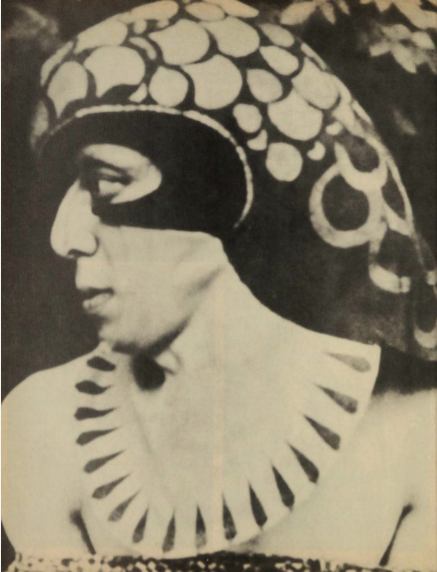

The story of At the Hawk’s Well is a spiritual search based on an Irish tale about an old man, a young man, and a shape-shifting hawk-like spirit who guards the water. Ito’s role was basically the spirit of a hawk, who utters a woman’s cry sounding from a well, like an oracle. He also choreographed movement for other scenes.

For a backdrop, theater director Gordon Craig designed screens (Preston 21), and artist Edmund Dulac collaborated with Ito on an Egyptian-style mask for the supernatural spirit of the Hawk (Cowell 2001, 12).

Hawk headdress ph Alvin Langdon Coburn, London, 1916

Ito brought two colleagues from Japan into the project because they knew the actual songs of Noh. It was through this play, through the blending of Yeats’s poetry and the songs of Noh, that Ito could appreciate the beauty of Noh for the first time. He saw an affinity between the wholeness of a Noh play and the Dalcrozian integration of dance and music. It was a kind of full circle whereby Ito’s interest in the West brought him to Europe, and it was Western poets whose interest in Asia brought him back to his Japanese roots.

For Yeats, Ito was the inspiration to write the play: “I [saw] him as the tragic image that has stirred my imagination.” Yeats felt he had invented a new form: a play with dance. But it depended on the brilliance and depth of Ito’s performance. Yeats wrote three more such plays, but he always had trouble with the dance component after Ito’s departure (Caldwell 52–54).

Coming to New York

The war continued to escalate, and Ito looked toward safety in New York. At that time, Japanese laborers were basically barred from the United States. But a producer named Oliver Morosco was able to offer Ito a three-year contract under a U.S –Japan arrangement called Gentlemen’s Agreement of 1907, which made exceptions for “a category reserved for students, intellectuals, and other ‘desirable’ professionals” (Wong 146). When Ito arrived in New York in 1916 and realized that Morosco was planning what Ito termed a “sex comedy,” he broke the contract (Caldwell 55).

Mary-Jean Cowell, longtime Ito scholar, describes the artistic environment of the city at the time:

There was no “modern dance” movement in New York when he arrived. Outside of ballet, most dancers who aspired to art rather than revues were music interpreters, aesthetic dancers, barefoot dancers, or exotic dancers, the latter mostly Caucasians in generic Oriental attire (Cowell, Ito Fnd).

In 1917 Ito joined Adolph Bolm’s Ballet Intime for an East Coast tour that would raise money for war charities (Caldwell 61). Bolm had been a star of Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes, and this was the first group he assembled after leaving Russia. One can imagine that, because Ito’s sighting of Nijinsky in Paris had ignited his dance desires, he must’ve been happy to dance with another of Diaghilev’s stars.

Ito’s solos fell into two categories: either culturally specific—e.g. Spanish, Javanese, French, Chinese—or his own, more or less abstract, amalgam. The latter were based on his two sets of ten arm gestures (A and B, or masculine and feminine, or sun and moon) and variations of them, not unlike Dalcroze Eurythmics.

Brochure for Ito school in NYC, with Ito family crest

According to Koner’s description, even his non-oriental style had cultural roots: “It had the purity and the clarity of a single brush stroke in a Japanese painting, and at the same time it was like a modern painting influenced by the Japanese style” (Koner 27).

Because these two styles weren’t entirely separate, they seeped into each other. For example, a certain kind of gliding could be used in both styles. In Koner’s words, “He knew how to cover space with the effortless gliding movement of the Oriental, skimming along the floor without the bouncing and shoulder wagging visible in many dancers” (Koner 27).

Ito called his works “dance poems.” He wanted each piece to be concise and focused, yet leave a lingering image, a liminal trail, a shadow. Helen Caldwell, who had studied and performed with him for years, called them “miracles of evocation” in her biography of him (Caldwell 4). She admired his subtlety: “He avoided spectacle . . . and relied upon suggestion rather than elaboration, believing that an idea, including emotion, exerts more power on the imagination when not completely revealed” (Caldwell 34).

In his diaries, Ito observed that “Eastern art is three-fourths spiritual; Western art is three-fourths material.” For him, that presented an imbalance. “True art should be one-half spiritual, one-half material” (Preston 23). His lifelong effort was to find such a balance. As Cowell and Shimazaki have put it, “This blend would be the ultimate universal and eternal art” (Cowell 2001, 13).

Michio Ito and Martha Graham

The experience of Hellerau meant he could work in dance or theater or take gigs that straddled the two. From 1918 to 1928 he designed sets or directed movement for a range of productions. Venues and groups include the Neighborhood Playhouse, Washington Players, the Provincetown Players, the American Opera Company, and John Murray Anderson’s Greenwich Village Follies.

Martha Graham in Ted Shawn’s “Serenata Morisca,” Greenwich Village Follies, 1924, Library of Congress

For the Follies, typically a blend of popular and art dance (Kendall 178-79), he choreographed and designed sets in 1919, and again in 1923. For this last, he “arranged” several numbers, among them an East Indian dance for The Garden of Kama, featuring the 29-year-old Martha Graham. (She also performed Ted Shawn’s Serenata Morisca in the Follies, see photo.) According to at least one historian, her admiration for Ito’s authenticity motivated her to leave the Denishawn company (Reynolds 145).

Ito rented a studio in Carnegie Hall, where it happened that Louis Horst, the pianist for Denishawn who became Graham’s music director and artistic advisor, had the studio upstairs. Eager to bestow a sense of form to the new barefoot dancing, Horst was looking for structures he could lend to Graham and other young dance artists. According to Janet Mansfield Soares, Horst’s biographer,

The pianist carefully observed the way Ito paid particular attention to the underlying dance rhythms in a Bach suite. In his classes in the studio below Louis’s, Ito taught phrases in unison, canon, and with changes of rhythm and talked about symbolism, imagery, and the use of minimal thematic materials — ideas that found their way into Louis’s teaching…As Ito…fed Louis information, he would then share it with Graham (Soares 60-61).

It was through Horst, then, that Ito’s ideas about choreographic structure reached Martha Graham.

Lillian Shapero, in her Enigma, 1936, Courtesy YIVO via Steve Weintraub

Horst not only brought these ideas to Graham, but he also taught dance composition classes at the Bennington School of the Dance (the cradle of modern dance) in the late ’30s and early ’40s, thus instilling his rules and standards to budding modern dancers. (One of them was Lillian Shapero, who studied with Ito, danced with Graham, and choreographed for Yiddish theater [email from Judith Bring Ingber].)

For me, it’s a revelation to know that Horst had absorbed so much about structure from Ito to pass on to the “pioneers” of modern dance. It also explains why it’s been said that Ito “deeply influenced” Graham (Phillips 38).

In addition to their time with the Follies, Ito and Graham both performed in the gala opening of the John Murray Anderson—Robert Milton School of the Theatre and Dance in November 1925, where they would both be teaching (Stodelle 45). They performed together again, this time with Benjamin Zemach in an Irene Lewisohn production called Les Nuages with music by Debussy (Jowitt email).

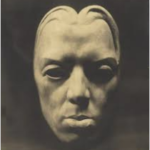

Noguchi head of Ito

Ito introduced Graham to his friend, the sculptor Isamu Noguchi. This was perhaps his greatest gift to her. The Graham-Noguchi collaboration, beginning with Frontier (1935), defined a spare yet sculptural, modernist look. Dating from her friendship with Noguchi, and possible even before that when she met Ito, she always felt an affinity for Asian dancers too. “I am deeply Asian in all of my interests,” she proclaimed (Stodelle 153).

Pauline Koner and the Tour to the West Coast

Also frequenting the Carnegie Hall studios was the young Pauline Koner, who later became an international soloist and a guest with the José Limón company. While taking Flamenco lessons on a lower floor, she heard a rumor that a “true Oriental” occupied Room 61 (the craze for Orientalism was as fervid in the U. S. as it was in Europe), and she ventured upstairs. It’s worth relaying her immediate reaction to Ito, as penned in her autobiography:

One of the most extraordinary faces I have ever seen. Shining black hair falling on either side of his oval face framed unusually large, luminous eyes, with a hint of sadness in them. His nose had a slight arch, almost Mayan in its contour, and a full and protruding lower lip lent a sensuous quality tinged with determination. This was not a handsome face, but a torn, and beautiful face. There was an outward calm masking an inner intensity that sent an electric current through me (Koner 23).

She signed up for private lessons and began to learn Ito’s slow, stately Javanese dance. After six half-hour sessions, Ito asked the 15-year-old Pauline to join his small company for a tour. They would be opening in New York and then going across country to the West Coast (Koner, “On Dance”). The other dancers had been with him for a while. But Koner had trained with Michel Fokine, so she brought her ballet lines and legwork to her roles.

The debut of this group took place at the Civic Repertory Theatre in Manhattan in December of 1928. Although Koner reports that the reviews were “encouraging” (Koner 29), a Billboard critic compared the group unfavorably to Doris Humphrey’s group (Rodman 135). Perhaps that’s why Ito then augmented the repertoire with a few more dances. He asked Koner to perform the ebullient Hungarian solo that Fokine had taught her, and he invited Georgia Graham, Martha’s sister, to dance two solos from the Denishawn rep. [Aside: In the 1960s, we all knew her as “Geordie,” the sister who kept attendance records at the Graham school.] These works were not given choreography credit in program notes or press releases, and Koner gives no hint of indignation. (Whether Fokine cared or not is another matter.) Conversely, the “ethnic dancer” La Meri danced took several Ito solos on her tour in the late ’20s without crediting him [Ruyter 34]. This lax attitude is certainly different from today’s policies of giving credit.

He probably didn’t mind La Meri’s “borrowing” his choreography because she’d studied with him, and he was generous to his students. He enjoyed teaching and giving his students opportunities (Caldwell 85; Rodman 146).

In his prime, Ito was a charismatic performer. Koner recalls his onstage presence with her usual descriptive powers:

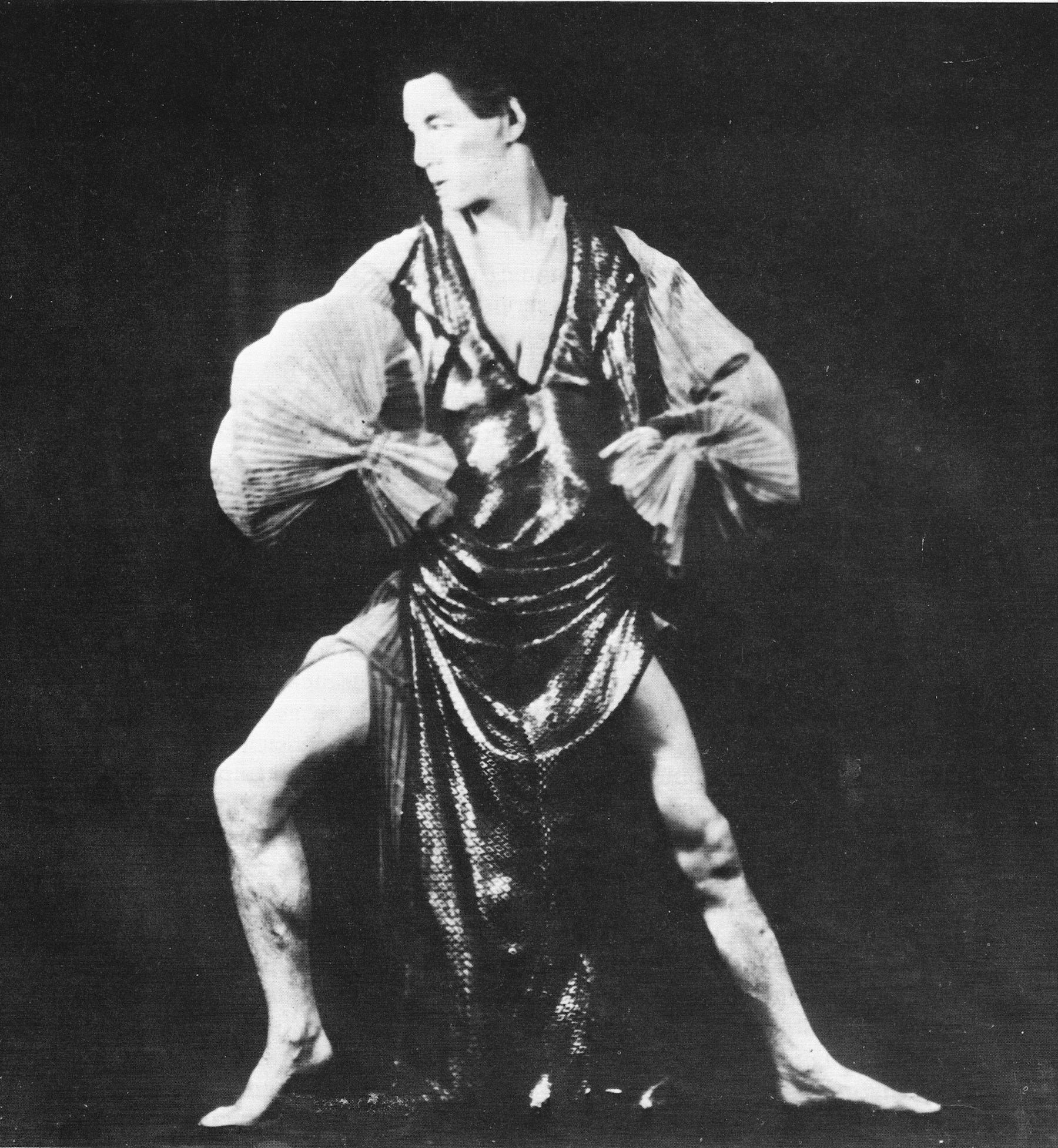

Ito possessed a magnetism that made all eyes focus on him. The moment he entered, the very air seemed to change. Space seemed infinite, and he could shape it to whatever size he wished —boundlessly open, or minutely pinpointed. In his Albeniz Tango Ito’s body was the entire space, concentrated within the confines of his own limbs, taut, intense, lithe as a puma, ready to pounce, but always held back. In his tightly fitted black trouser, short jacket, and jaunty black-trimmed Spanish hat, he was the essence of a Spanish dancer without doing a single true Spanish step (Koner 29).

Tango, 1926, photo Toyo Miyatake Studio

The small group traveled by Pullman train to Detroit, Chicago, Kansas City, El Paso, Seattle, and San Francisco. They typically performed a program of 20+ solos, duets, and trios, with the audience often demanding encores of several pieces (Moore 24). Most of his works, according to Koner, could be done by either a man or a woman (Koner 28).

By her own admission, Koner “worshipped” Ito as both a man and a dance artist. She was hungry to learn from him. On tour, she writes,

We often gathered in Michio’s room, where he sat crosslegged at the head of his bed while I, being the smallest, found room at the foot . . . He talked of emotion and logic controlling life, the need to discover new movement, the importance of contrast, the balance of opposition, and the nuance of shading (elements Doris Humphrey emphasized in later years). The first time I heard the term A-B-A, I was sitting at the foot of Michio’s bed (Koner 36).

Here Koner supports the idea that Ito brought musical structures to his teachings early on.

After their final performance in March, they were stranded. Ito and the dancers were broke; Koner had to wire home for money. She and Hazel Wright, the dancer married to Ito, took the train home to New York. Wright had left their two small sons with relatives (Koner 36-37). Ito stayed in California. It was the Depression and hard to get work everywhere. But he’d done one Hollywood film, and thought he could book more (Cowell email).

A Utopian, Socialist, Communal, Impossible Dream

Toward the end of his time in New York, Ito had bemoaned the dearth of space for dance. “Everything from Grand Opera to burlesque has its own building, its own home,” he pointed out, “but dancing has no place!” Frustrated, too, by the constant necessity to earn money to support his choreography, he began to imagine a community of dancers who would share rehearsal and performance space. He came up with a plan: the New York Dance Guild. According to a feature article in The American Dancer by its editor, Ruth Eleanor Howard, in February 1929, the New York Dance Guild would be a home for dancers (Howard 9).

On a rooftop in NYC, 1919

Ito envisioned a new building where dancers would pay a monthly fee toward renting space. He even chose the architect — Hugh Ferris — and the site — on the East River between 54th and 55th Streets. He claimed he had pledges from 136 dance artists who would participate to the tune of $200 rent a month. This, he reasoned, would help defray the cost of construction, for which he would obtain a three-million-dollar loan. The building would have two theaters—a 600-seat and a 1,000-seat—a swimming pool, a library, and a roof garden, as well as plenty of studios for working and apartments for living. According to his math, the building would repay the loan and make a profit within five to seven years. In Howard’s account, Ito said he presented this proposal to some people with money, and within three minutes “these gentlemen” agreed to make the loan. (Howard 22). Exactly who these “these gentlemen” were was not divulged.

It’s kind of an astounding vision, like a year-round Jacob’s Pillow, or like the Ailey hub in midtown Manhattan, but with living space included. Ito’s vision of community was as impractical as it was lofty.

We know from scholars that Ito tended to fabricate stories (Cowell 2001,12; Rodman 83). It’s possible he drummed up interest in the New York dance community, but it’s doubtful he ever presented his proposal to potential donors. (However, Cowell told me in an email that one newspaper reported that he did bring the proposal to someone of financial means.)

Scholar Tara Rodman traces this communal, idealistic notion back to an artists’ retreat in Connecticut that Ito attended with his students in 1921:

Itō hatched his own plan… the major nations involved in the peace talks would each donate the cost of one battleship, and this fund would go towards the founding of an international dance school that Itō analogized to the Red Cross—able to enter any country, it would bring together youth from across the globe in the harmonious study of dance (Rodman 186).

According to a memoir he wrote, Ito went to Washington, DC, and spoke with various ambassadors and President William Harding himself. Although this is probably fantastical, his concluding sentiment is significant: “It would be my life’s work to promote peace through the stage” (Rodman 187).

He transplanted his dream of peace, of bridging communities, to Los Angeles.

The Ito-Horton-Ailey Thread

Ito’s first performance in Los Angeles was April 28, 1929, at the Figueroa Theatre. This must’ve been a solo concert since his dancers had returned to New York. Afterwards, he immediately received an offer to teach at the Edith Jane School of Dancing. His stint as her first internationally known guest teacher was announced in the May 1929 issue of The American Dancer, along with the statement that “Mr. Ito’s enthusiasm for the West and its eager young disciples of the dance is unbounded.” (There seems to have been a thin line between news and advertising at that time.) He set up classes for advanced students as well as a weekly community class for non-dancers, with a discount price for those of Japanese descent (Rodman 152).

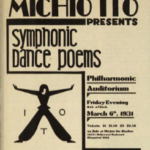

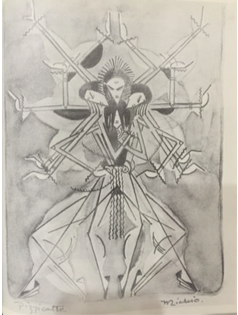

Poster with drawing by Ito

For five Monday evenings that summer, he brought students to perform at the 300-seat Argus Bowl, where he remounted his production of Yeats’s At the Hawk’s Well. This time, the role of the Guardian Hawk went to Lester Horton, a talented student in his professional-track class.

Caldwell, who had watched Ito rehearsing Horton for the role, describes the dancing:

The hawklike Guardian, as composed by Michio Ito, was, in fact, a modified Noh dance—tense, continuous movement with suble [sic] variations on its monotony, inducing a trancelike state in both personages and audience —but its increase in tempo was more rapid than in genuine Noh and arm movement was broad and smoothly dramatic, recalling Egyptian representations of the hawk with spread wings and giving a feeling of a great bird’s gliding and wheeling (Caldwell 45).

A Los Angeles Times critic raved about Horton: “Lester Horton, the hawk, surpassed my earlier good impression of his artistic accomplishments. He is rhythmic, poetic, pliable and touched with the spirit of ‘make believe’ (Prevots 185). This mention no doubt helped Horton set up his own company in 1932.

Horton, who became a modern dance pioneer—and mentor to Alvin Ailey— in Los Angeles, was strongly influenced by Ito. Horton’s biographer, Larry Warren, wrote that,

As a performer Ito had an enormous personal dynamic. Horton was able to observe and study the stage projection of a competent artist who could command the attention and interest of his audience by the stateliness of his bearing and the clarity and forcefulness of his projection of gesture. His body spoke eloquently; his facial expression was calm, mask-like. These performance skills were integrated into Horton’s understanding of theater dance and later he was able to refine them and pass them along to his dancers (Warren 31).

The Lester Horton Dance Company is often credited with being the first modern dance company to be racially integrated. It famously included Carmen de Lavallade and Alvin Ailey as well as Bella Lewitzky and Joyce Trisler. But Cowell has pointed out that Ito’s integrating of white and non-white dancers came first (Homsey DVD).

In Hollywood — In Community

Ito was teaching and rehearsing in Victoria Perry’s studio in Hollywood Hills—where Agnes de Mille and Carmelita Maracci also rented space (Homsey DVD). Ito’s own schools had spread to six sites throughout L.A. (Rodman 154). For at least some of his time in California, he also taught at the Denishawn school. In a 1926 interview, he described his teaching:

My teaching embraces the ballet, which trains the legs; acrobatic dancing, which trains the body; Oriental dancing, which trains the arms; and Dalcroze Eurhythmics, which develops the brain control of all three (Cowell 2001, 13-14).

He drew on his students to populate the next phase of his creativity: large-scale pieces that he called “symphonic choreographies.” Venues like Pasadena’s Rose Bowl and the Hollywood Bowl allowed Ito to produce events he never could have dreamt of in New York.

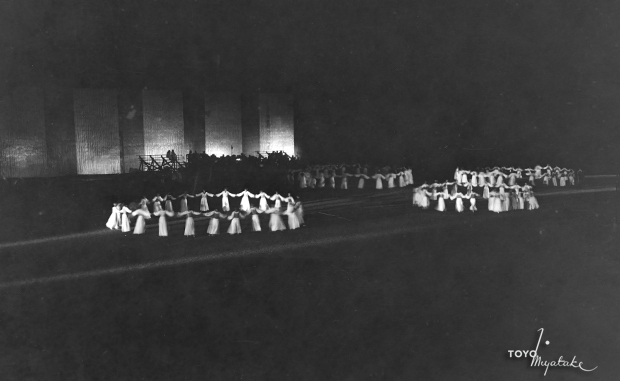

“New World Symphony,” Pasadena Rose Bowl, 1929, photo Toyo Miyatake Studio

The first of these, in September 1929, was the “Pageant of Lights” to celebrate the new floodlights at the Pasadena Rose Bowl. With a cast of 150 dancers, Ito divided them into groups of 24. The Los Angeles Philharmonic and 200 singers performed music by Tchaikovsky, Chopin, Grieg, and Dvorak. His go-to stage set was a gold, folding screen 40-feet high by 125-feet long, reminiscent of Craig’s screen for the Yeats play.

As spectacular as all that was, it was Ito’s signature solo, Pizzicati (sometimes called The Shadow Dance), that brought the house down. This solo, with feet planted wide and arms and head moving in time to the Delibes music while casting a humongous shadow, possessed what Caldwell called a “mystifying power” (Caldwell 79). According to a review in the Pasadena Star News, Pizzicati was the climax of the show: “A slim black figure silhouetted in startling relief against an enormous gold screen,” wrote the reviewer, “dominated the Rose Bowl and held the crowd of five thousand people spellbound and silent” (quoted by Caldwell 88).

Pizzicati (1916), photo Toyo Miyatake Studio, 1929

The stock market crashed the next month, and the “Pageant of Lights” was never to be repeated.

The following summer, however, Ito mounted Borodin’s Prince Igor at the Hollywood Bowl. For this performance, he mobilized groups from the University of Southern California, as well as from the Los Angeles Playground Department and the Japanese-American Women’s Association, to either perform or help build sets and costumes. Prince Igor had a cast of 125 dancers, a 100-person orchestra, and the 200-person Mormon Chorus.

As one can glean from his magnificent costumes and striking drawings, Michio Ito had a visual command as well as a choreographic command. The visual aspects, especially with the various platforms, harked back to his time in Hellerau. Ito’s visual aplomb also had the ability to deflect the eye from the less-than-professional level of some of the dancers (Rodman 156).

Greene reviewed it in Los Angeles Examiner: “The whole spectacle was a triumph of gorgeousness that inspires the hope for others of its kind. Such an artist as Ito is an asset to the community” (Prevots 187).

The American Dancer made much of his contribution to the community. Lewis Barrington, who had traveled with Ito’s touring group as the lighting technician, wrote a piece in the July issue attesting to the “growing momentum” of the “Community Dance movement” in California (Barrington 16). He quoted Bertha McCord Knisely reporting that Ito

believes that the dance is the most natural outlet for human aspiration toward higher activity than the mere utilitarian things of life. He has a vision of community dancing which shall be a step beyond the community singing idea . . . we hope that Michio Ito and his dance have come to stay and to be a part of our striving for those things that nourish man’s ‘divine vitality.’ (qtd in Barrington)

California was ready for Ito. And yet . . .

The Dark Side of Orientalism

While the Californians were as enamored of Orientalist exoticism as Europeans, the anti-Asian sentiment was growing, stoked by the media. The “Yellow Peril,” a term coined to indicate the threat that Asian laborers would take away work from whites, led to harassment and beatings. Hollywood depicted Asian characters as conniving, menacing, and barbaric. Various laws prevented Asians on the West Coast from buying land or marrying a white person. (Cowell 1994, 276; also see Mel Wong “Unsung Heroes of Damce History”).

And yet Ito agreed to work on six Hollywood movies, either as a movement director or as an actor. The first was Dawn of the East (1921), in which he played a villainous character. For No, No, Nanette (1929–30), he contributed a “Japanese ballet.” For the Henry Fonda movie, Spawn of the North (1938), he played a Native American and prepared ceremonial dances. For Sunset Murder Case (1938), he created a gliding dance for a group of women. In Booloo (1938), as the “chief of a savage Sakai,” he wore a ridiculous get-up, representing, as Cowell noted, “an irrational, primitive tribe of “Others,” an image which is an implicit argument for the hegemony of Eurocentric civilization and for white supremacy.”

Ito, at left, as Sakai chief in Booloo (1938)

Noticing that Ito never told stories about these experiences, Cowell writes that it was probably “a painful collision of Ito’s lofty vision of a universal art and contemporaneous socio-political factors” (Cowell 1994, 276). Meaning racism.

Pearl Harbor, the FBI, and the Artist as Saboteur

The fact that the U. S. and Japan were at war threw Ito into turmoil. In a post-war memoir, he wrote,

Japan is the land of my birth. America gave me my education and reared me. That these two countries should be at war astounded and confused me. As time passed the seriousness of this situation filled me with a trembling fear. As an artist, my hope was to build a bridge between Japan and America…so that a new and higher civilization could be developed (qtd in Cowell, Ito Fnd)

The FBI began watching Ito in 1939. He was not only Japanese-born, but he had an “artistic temperament,” which marked him as unpredictable, thus capable of sabotage (Riordan 24). Right after the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, the FBI raided Ito’s home and arrested him. He was sent to a series of four Department of Justice camps in Montana, Oklahoma, Louisiana, and New Mexico (Rodman 188). He had the distinction of being one of only 770 (out of 110,000) who were incarcerated as “enemy aliens” and suspected of espionage (Riordan 67). These Justice Department camps were not the usual internment camps where families could at least stay together. They held Europeans as well as Japanese. As Kevin Riordan quipped, “Even Ito’s internment was international’ (Riordan 85).

Another view of Pizzicati

At the hearing of the Enemy Alien Board in 1942, the first of eighteen “Findings of Fact” was that “Subject is an alien enemy;” the second states that Ito is an “artist of artistic temperament.” Another “finding,” recorded as though it were a joke, was “That the alien also made a statement, the gist of which is that he believes in the ‘world brotherhood of man’ ” (Riordan 80). (Note: in February, President Biden apologized to Japanese Americans for the U. S. government’s racist action of incarcerating their families during World War II.)

Ito felt betrayed by the United States. Before the war, he resisted identifying as Japanese: “In my dancing, it is my desire to bring together the East and the West. My dancing is not Japanese. It is not anything—only myself” (Cowell, Ito Fnd). In the internment camps, he bonded with his fellow prisoners. He started to let go of his individuality as an artist and embrace his Japaneseness. As Rodman writes, “For Itō, imprisoned in a bleak camp, the Japanese Empire seemed to offer the promise of cosmopolitanism that the West had betrayed” (Rodman 191).

In his notebooks during these terrible times, Ito questioned the nature of being human and the nature of civilization, always trying to reconcile the difference between the cultures of East and West.

What is a civilization? I think it is about how we exist together and its culture examines the aesthetics of that existence…. America is a young country and the concern is about an easy existence, whereas in the East, the focus is on the beauty of existence. When the easy existence is solved, the next effort will be to exist beautifully (Homsey, based on Ito’s writings).

In 1943, Ito requested, and was granted, repatriation. He and his second wife, Tsuyako, sailed to Japan as part of a prisoner exchange (Rodman 193).

Return to Japan

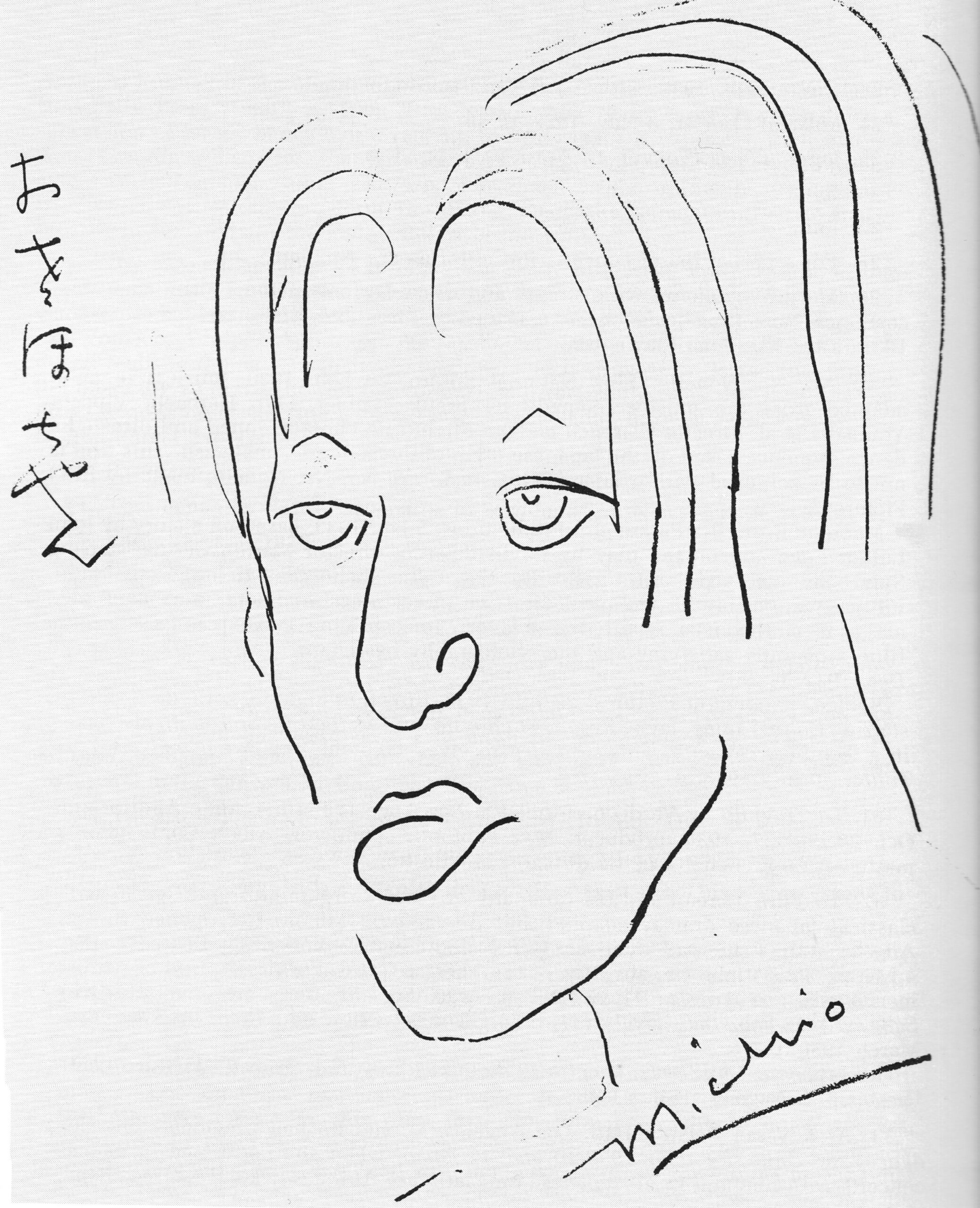

Self caricature 1937

As he had dreamed up the New York Dance Guild in New York, and an inclusive community in California, Ito now proposed The Greater East Asia Stage Arts Research Institute. He envisioned a series of pageants, street theater, and musicals that would highlight the diversity of cultures in Asia (Rodman 263). Likening these grand notions to Hellerau, Rodman writes that the Institute “recast the internationalism of Hellerau as a Pan-Asian cosmopolitanism” (Rodman 197). After months of planning, the Institute produced only a single performance before the battering of American bombs forced Ito and family—and some students— to flee to the countryside in the spring of 1945 (Rodman 200).

Oddly Bridging East and West

It seems like a sharp irony that soon after Ito was labeled an enemy spy by the American government, he was hired by the U. S. Army to produce lavish shows for American G.I.s in Occupied Japan. Clearly, he was no longer suspected of being a spy. In fact, his native-born knowledge of Japan was an asset to the Allied Occupation. And from the other side, the Japanese had bestowed on him the status of “foreign expert” through his articles on etiquette in women’s magazines, for example, showing women how to walk wearing the tight skirts then in fashion in America (Rodman 224-25). This visibility led, in 1953, to Ito starting a training program in a fashion school for “make-up, hair styling, movement, etc. classes in decorum and appreciation for music, art, film and literature” (Cowell, emails).

Sakura Flowers, Ernie Pyle Theatre, Tokyo, 1947

The Ernie Pyle Theatre, named for a heroic American journalist, provided the only entertainment for the 350,000 American personnel stationed in Japan. And Michio Ito was the only person who could have produced the spectacles that would appeal to American G.I.s. — young men desperate for a hit of Americana but needing to learn about the culture they now inhabited. Ito’s experiences in the U. S. prepared him for this responsibility, which was to choose, direct, and choreograph for a cast of mostly Japanese women. Operating from 1947 to 1952, they had titles like Jungle Drums, Sakura Flowers, and Rhapsody in Blue.

Sakura Flowers, Ernie Pyle Theatre

Itō used this knowledge to stage an image of Japan as a land of rich cultural traditions, modern sophistication, and exotic allure. Befitting the Ernie Pyle’s reputation as the Radio City Music Hall of the East, Itō consistently shaped these images through the fantasy of the revue (Rodman 231).

While it seems outrageous to me that the U. S. government would expect this work of Ito after incarcerating him, scholar Tara Rodman has another take:

One gets the sense that although for many Japanese, the Ernie Pyle was a painful symbol of the complicated sense of exclusion and opportunity wrought by the Occupation, for Itō, it offered a sort of return to his adopted home, while remaining in the nation of his birth (Rodman 233).

Ito’s dream to bridge the cultures of the East and the West may have been partly fulfilled.

Ito rehearsing Rhapsody in Blue, 1947

Ito’s Last Idealistic Plan

In 1960, the Japanese government chose Ito to produce the opening and closing ceremonies for the 1964 Olympics. They wanted to show that a flourishing new Japan had rejoined the international world. Ito envisioned the torch relay as a pan-Asian journey that would celebrate the different cultures, from Greece to Japan, with dances and music from all regions performed along the way (Rodman 261-62). He was still building bridges, but instead of bridges between East and West, this time it was between all the Asian nations. But in 1961, Ito died suddenly of a cerebral hemorrhage.

His protegée and assistant, Ryuko Maki, took over his studio and kept it running for fifteen years. In 2006, he was recognized with a two-hour documentary produced by Japan’s Public Broadcasting Company, NHK, entitled Michio Ito – an Artist Abroad. The Michio Ito Foundation, which licenses his works, has been overseen by his granddaughter, Michele Ito, in California.

Pizzicati drawing by Ito

Revivals of Ito’s Work

A young student named Satoru Shimazaki attended a performance by Ryuko Maki and was struck by her drama and authenticity. Shimazaki had been disappointed by the techniques of ballet and Graham, so he enrolled in the Ito school, which was then headed by Maki. He became well versed in the Ito method and came to New York in 1971 to study other styles. He started performing his own choreography at venues like The Kitchen, then in SoHo. Realizing how little was known about Ito, he decided to mount reconstructions of his work (Chin). In 1979 he invited Maki to perform and to set her mentor’s works, the result being “A Memorial Festival of the Choreography of Michio Ito,” at Jean Erdman’s space, the Theater of the Open Eye. Ito’s nephew, Teiji Ito, who was then the musical director of Jean Erdman’s company, introduced the evening, and Erdman narrated the lec-dem portion.

As guest artist, Maki danced two of Ito’s signature solos: Pizzicati and The White Peacock. Muna Tseng, a member of Jean Erdman’s company who performed in this evening, described Maki as “a dynamo” in Pizzicati. In the archival video (viewable by appointment with the Jerome Robbins Dance Division at the NY Public Library for the Performing Arts), her musicality is impeccable, with strong accents in the wrist action.

The White Peacock, as Tseng recalled, was “highly Orientalist . . . the costume was amazing, almost like Folies Bergères” (Tseng). When I watched the video , I saw Maki wearing a long trail of tail feathers. There was a stunning moment when, after Maki does something inscrutable with her fingers, the train of feathers suddenly springs up to become a huge disc behind her. (The magic of strings, no doubt.)

Tseng also described being coached by Maki:

It was fascinating, really. I found the technique, the physical moving, quite musical. We would do almost Isadora Duncan-y runs and leaps and little jumps. I remember it was lyrical and very precise with the hand and arm gestures (Tseng).

While coaching, Maki encouraged the dancers to be soft. “I remember one rehearsal [when] Miss Maki kept going, ‘Don’t go up so high in relevé,’ and ‘Don’t get so stretched up’ ” (Tseng).

In an interview in advance of this Memorial Festival, Maki recalled Ito’s stage persona: “He looked like a black tiger in Tango. It was the direction of the eyes, as concentrated as a Japanese samurai” (Dunning).

Shimazaki too was a charismatic performer; like Ito, he had an androgynous look. His rendition of Tango was contained and elegant. The pacing was so measured that the occasional stamp for rhythmic accent created a momentary thrill.

Critics were respectful about Ito’s work but did not claim it to be revelatory. Deborah Jowitt, writing in the Village Voice, wasn’t wowed by these short dances but valued “their simplicity and their ardent clarity.”

To today’s eyes, Ito’s work looks limited in range of motion and dynamics. The music visualization aspect is quite literal, meaning that the motifs are repeated often to match the musical motifs; in the duets and group works, the interaction is minimal. But these are foundational studies at the dawn of modern dance, and they helped move the art forward. As we’ve seen via the experiences of Koner and Horst, Ito’s teaching was perhaps more influential than his choreography.

Burgess in Pizzaccati. ph Mary Noble Ours

In 1996, Shimazaki coached a similar evening, this time with Dana Tai Soon Burgess Dance Company in Washington, DC. This fared better with at least one critic, perhaps because Shimazaki emphasized the drama of Ito’s life. During the Burgess evening, Shimazaki told the audience, “World War II tore out his heart, and his life” (qtd in Kaufman).

Critic Sarah Kaufman enthused about the dances in The Washington Post: “What was truly revelatory was the fact that the passage of time has not dimmed their power or made them mere curiosities from the beginnings of modern dance” (Kaufman).

Burgess, whose company continues to perform and discuss Ito’s work, gives a lecture online about Ito’s work that is full of insights. Whereas some have perceived the figure in Pizzicati to be a puppet or a military leader, Burgess finds a deeper meaning:

His shadow psyche is larger than life . . . a giant shadow expressed his surreal state. Pizzicati is aligned with the growing psychological theories of Carl Jung and Sigmund Freud. It exemplified the shadow self, the unconscious influencer of our conscious actions that is hidden in our inner emotional terrain.

Burgess believes Ito’s work includes a moral component. In the lecture he says, “that the shadow resides in all of us and that we must become cognizant and responsible for our actions” (Burgess).

Repertory Dance Theatre in Salt Lake City has been performing Ito’s works since 1992. In 2007 they received an American Masterpieces grant from the National Endowment for the Arts to support the Ito repertoire, especially in educational settings (and create this brief documentary)

En Bateau, performed by Repertory Dance Theatre

Other groups that have restaged Ito’s works include Los Angeles Dance Foundation, Chamber Dance Company at the University of Washington in Seattle, and CityDance in Washington DC.

Current scholars have put forth different opinions as to whether Ito was primarily transnational, or Japanese, or cosmopolitan. As Rodman has pointed out, “early efforts to reclaim his place in the modernist and modern dance canon have shifted to interrogations of how race and ethnicity shaped his career” (Rodman 20).

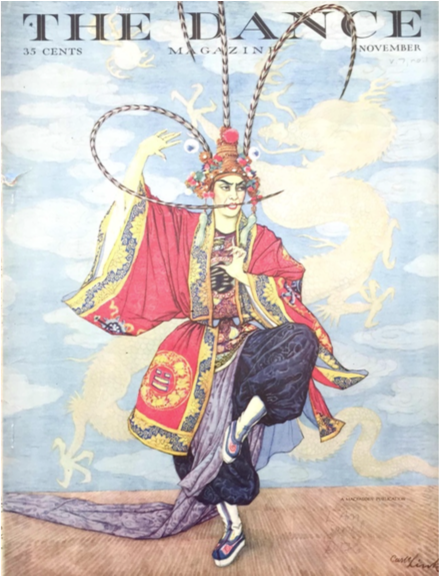

Is Michio Ito part of the modern dance canon? Should he be part of it? To hell with the canon. We teach what is valuable or nourishing at a particular time. In 1926, Ito graced the cover of The Dance magazine, a precursor to Dance Magazine. The June 1960 issue of Dance Magazine called Ito “Japan’s elder statesman of dance” (Bowers). And the Dance Heritage Coalition has named him one of America’s Irreplaceable Dance Treasures. With the deluge of recent scholarship—and more on the way—he will eventually be more recognized and studied.

The Dance Feb. 1926 “Impression of a Chinese Actor,” by Michio Ito, drawing by Carl Link

Appendix

Side Trip to Other Ito Fables

Here’s another example of a cockamamie scheme to make money, as told by his friend, the sculptor Isamu Noguchi:

He [Ito] asked me to do some masks for Yeats’ play, “At the Hawk’s Well,” a Noh play, I did these masks. He got me to do them with the idea that he would present it and with that he would make some money and with that money he would buy some motion picture houses in Japan and with the money he would make from the motion picture houses in Japan, he would buy an island in the sea and we were all going to retire there. (JRDD recording)

Noguchi was also under the impression that Ito had danced with Pavlova. Perhaps Ito had told him a variation of the story he told Barbara Perry, a longtime student, who recounted the story in Homsey’s documentary:

They had a big benefit in Paris and Pavlova did Pizzicato Polka and flitted from one side of the stage to the other and then when she took her bows she said, “Ladies and Gentlemen, in the audience is the great dancer Michio Ito. Ito, take a bow.” He stood up and took a bow, and she said, “Dance for us, Ito.” And he said, I have no music . . . Yes.” And he went onto the stage and he said to the musician or musicians, “Play the Pizzicato Polka again.” And he stood in second position and he did the whole dance with his hands (Homsey DVD).

Rodman generously calls these tales an “act of self-invention through narrative registers” (Rodman 96). Perhaps these stories are a result of the necessity of having a fluid identity.

§§

Special thanks to Mary-Jean Cowell, Muna Tseng, Bonnie Oda Homsey, Deborah Jowitt, Linda C. Smith of Repertory Dance Theatre, Michele Ito of the Michio Ito Foundation, Daisy Palmer and Tanisha Jones of the Jerome Robbins Dance Division of the NY Public Library for the Performing Arts, and to Steve Weintraub and Dancing Jewish Google Group.

Works Cited

Books

Caldwell, Helen. Michio Ito: The Dancer and His Dances. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1977.

Pauline Koner. Solitary Song. Durham: Duke University Press, 1989.

Phillips, Victoria. Martha Graham’s Cold War: The Dance of American Diplomacy. New York: Oxford University Press, 2020.

Prevots, Naima. Dancing in the Sun: Hollywood Choreographers 1915–1937. Ann Arbor: UMI Research Press, 1987, pp.175–195.

Ruyter, Nancy Lee Chalfa. La Meri and her Life in Dance: Performing the World. Gainesville: U Press of Florida (2019).

Soares, Janet Mansfield. Louis Horst: Musician in a Dancer’s World. Durham: Duke University Press, 1992.

Stodelle, Ernestine. DeepSong: The Dance Story of Martha Graham. New York: Schirmer Books, 1984.

Warren, Larry. Lester Horton: Modern Dance Pioneer. Princeton: Dance Horizons, 1977.

Scholarly Essays and Dissertation

Cowell, Mary-Jean. Research assistant: Satoru Shimazaki. “East and West in the Work of Michio Ito.” Dance Research Journal, Fall, 1994. Accessed March 20, 2021.

Cowell, Mary-Jean. “Michio Ito in Hollywood: Modes and Ironies of Ethnicity.” Dance Chronicle, 2001, Vol. 24, No. 3 (2001), pp. 263–305, https://www.jstor.org/stable/1568133 Accessed March 23, 2021.

Preston, Carrie. “Michio Ito’s Shadow: Searching for the Transnational in Solo Dance.” Onstage Alone: Soloists in the Modern Dance Canon. eds. Claudia Gitelman and Barbara Palfy. University Press of Florida, 2012.

Riordan, Kevin. “Performance in the Wartime Archive: Michio Ito at the Alien Enemy Hearing Board.” American Studies, Vol. 55/56, Vol. 55, No. 4/Vol. 56, No. 1 (2017), pp. 67-89 https://www.jstor.org/stable/44982620, accessed April 5, 2021.

Rodman, Tara. “Altered Belonging: The Transnational Modern Dance of Itō Michio, A Dissertation.” Northwestern University, Field of Theatre and Drama, June 2017.

Sato, Yoko. “At the Hawk’s Well: Yeats’s Dramatic Art of Visions.” Journal of Irish Studies, 2009, Vol. 24 (2009), pp. 27-36. https://www.jstor.org/stable/27759624 Accessed April 14, 2021.

Wong, Yutian. “Artistic Utopias: Michio Ito and the Trope of the International.” Worlding Dance, ed. by S. Foster. Palgrave Macmillan UK, 2009.

Other Articles

The American Dancer, unattributed articles in the June and July, 1928 issues.

Barrington, Lewis. “Community Dancing.” The American Dancer, July 1929.

Bowers, Faubian. “Meanwhile, on Tokyo TV, jazz become popular.” June 1960, Dance Magazine, June 1960, p. 38.

Chin, Gwin, “Can Isadora Duncan Solos Be Danced by a Man?” The New York Times, Jan. 3, 1982, Accessed May 4, 2021.

Cowell, Mary-Jean. Biography for Michio Ito Foundation website.

Jowitt, Deborah. “In Thrall to Meaning,” Village Voice, Oct. 15, 1979, Muna Tseng archive.

Kaufman, Sarah. “The Power of Michio Ito.” The Washington Post, Jan. 22, 1996, Accessed May 29, 2021.

Moore, Rose, “In the Spotlight,” The American Dancer. Feb. 1929, p. 24.

Stoop, Norma McClain. Review. Dance Magazine, Jan. 1980, p. 28.

Traiger, Lisa. “Dance Masters from Coast to Coast.” washingtonpost.com, posted June 3, 2005, Accessed May 11, 2021

Other Resources

Anonymous “Dance On” Video, 1984. https://video.alexanderstreet.com/watch/pauline-koner. Accessed May 11, 2021

Interview with Isamu Noguchi, interviewed by Toby Tobias, 1979, Jerome Robbins Dance Division, Dance Oral History Project, NY Public Library for the Performing Arts

From Los Angeles Dance Foundation, 2013

Michio Ito: Pioneering Dancer-Choreographer – Trailer, Directed and executive produced by Bonnie Oda Homsey. The DVD is Available on Amazon

From Repertory Dance Theatre, 2012

Linda C. Smith, Artistic Director:

- Selected Choreography of Michio Ito

- Michio Ito – Mystique, a Lecture -Demonstration

- Michio Ito – Spirit, includes En Bateau, Pizzicati, Gollywog’s Cakewalk, Ball, etc.

Websites

“Appia, Adolphe,” 1862-1928. Ref.: Exhibition of Eurhythmic Dance at the Hellerau Institute. JSTOR, jstor.org/stable/10.2307/community.13915725. Accessed 10 May 2021.

Unsung Heroes of Dance History 11