The Inheritance, a series of photos of Sybil Shearer by Helen Morrison, Morrison-Shearer Foundation.

John Martin called her a “remarkably creative maverick.” (Martin, 1963) Ted Shawn wrote that she had “the unmistakable marks of true greatness.” (qtd. in Shearer 2006, 339) Walter Sorell noted her “extraordinary originality.” (Sorell, 213) Walter Terry called her a “weaver of magic.” (Terry 1956).

In the 1940s Sybil Shearer was acknowledged as a leader of the avant-garde along with Merce Cunningham. In fact, Terry wrote that the two “have retained almost exalted positions as the king and queen of the avant-garde—others come and go, but they stay on.” (Terry, 1956)

Shearer certainly wove her magic during her 1941 solo debut concert at Carnegie Chamber Music Hall. So much so that after she left New York for the Midwest, John Martin and other critics traveled to see her whenever she performed in the Chicago area.

[Aside: I saw her dance at Ravinia in 1970 and never forgot her. Though I don’t remember the title of the piece, I remember an intense, riveting figure shaking and shimmering, with light flecks coming off her. One couldn’t look away.]

Shearer eventually faded from view to all but dance lovers in Chicago, where her name is still—or again—golden. One wonders, is a modern dance solo practice enough to secure a place in dance history? Was Shearer’s uniqueness, her otherworldliness, only worthy to the field for a finite period? Can her work, in some form, return to inspire current dancemakers?

Given the consistent raves in the 1940s, it’s remarkable how rarely her name appears in scholarly anthologies of national scope. Like Anna Halprin, Shearer left New York, escaping the orthodoxies of the day. I don’t think her ideas cut through the cloth of dance history the way Halprin’s did, but still, she deserves a place in our awareness.

In the 1990s Shearer became a dance critic, writing for the invaluable journal Ballet Review. Embedded in these reviews are clues to her philosophy of dance and art. Also, her three-volume autobiography, titled Without Wings the Way Is Steep, sheds light on major figures like Martha Graham, Doris Humphrey, Agnes de Mille, John Martin, Hanya Holm, and Louis Horst. (Note: this book, at least the first volume, is more of an annotated compilation of previous letters and other writings than a conventional autobiography.)

Early years

Born in Toronto, Shearer grew up in Nyack, NY, Long Island, and Newark, NY. When her mother played the piano, she danced—“always conscious of unseen forces I called fairies” (Shearer 2006, xx). At 4 she started taking ballroom lessons, but what she remembers most is the terror of beginning to dance—a stage fright that followed her into her professional life.

At home in Long Island c. 1920

At age 10 or 11, Shearer saw Anna Pavlova perform and “became filled with dreams.” She managed to get the great ballerina to sign her program. “I had fallen in love with her, with the dance, with the theatre.” (Shearer 2006, xx) Hearing of Pavlova’s death in 1931, Sybil felt bereft; she referred to the ballerina as a fairy, enshrining her as a representative of those unseen forces. She started taking ballet lessons with Grace Miles, who also taught society ladies like the wives of Alfred Vanderbilt and Florenz Ziegfeld.

As a literature and theater student at Skidmore College, Shearer often wrote letters to herself, sometimes addressing them to “My Dear Unknown” (Shearer 2006, xxii). (That word “unknown” was to surface later, perhaps as an adult version of a fairy.) While still a student, she saw the Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo and somehow met the choreographer Léonide Massine. (She had no compunctions about meeting whomever she admired from afar—Agnes de Mille, Katherine Dunham, Sol Hurok.) She didn’t like the dancing or the choreography. It wasn’t until she saw a book in the library called The Modern Dance (1933), by John Martin, that she felt pulled toward this more contemporary form.

The Bennington School of the Dance

After graduating college in 1934, Shearer headed to the first summer of what was to become the cauldron of modern dance, the Bennington School of the Dance. The summer session served two functions: First, to give the “four pioneers” of modern dance—Martha Graham, Doris Humphrey, Charles Weidman, and Hanya Holm—the space to create new works. Second, to grow this larger thing called modern dance and spread the gospel across the country. Many of the students were women who were teaching in physical education departments in high schools or colleges. Very few were destined to become professional dancers; among those few were Alwin Nikolais, Merce Cunningham, Anna Halprin, Louise Kloepper, and Shearer.

Hanya Holm, 1930s, Bennington College Archive

Shearer liked Doris Humphrey’s class immediately, but she was absolutely rapturous about Hanya Holm. Holm seemed wild and free compared to the restrained Humphrey, and Shearer made no secret of her enthusiasms. In the mornings, as related by Nancy McKnight Hauser, Sybil would wait on Holm’s front step until the choreographer practically tripped over her. (qtd. in McPherson 258)

Although Shearer had studied ballet and ballroom, she was a beginner in modern dance. In a conversation among faculty members looking back, composer Norman Lloyd recalled, “Everyone advised her [Shearer] to drop this idea of dancing…but she just kept on working and working by herself, and eventually she ended up in Doris’ company.” To which Bessie Schönberg added, “Every time you opened any studio door, there was Sybil on the floor working.” (McPherson 231)

Dancing on Commons lawn, ph Thomas Bouchard, Bennington College Archive

The grassy fields on the sprawling Bennington campus beckoned almost as much as the studios. Of her outdoor forays, Shearer reports the following reactions: “Flock by flock the cows, horses and sheep came from their pastures and looked over the fence at me. The cows were the most impressed, because they find it so hard to move quickly.” (Shearer 2006, 21)

She found Louis Horst’s composition class to be “agony in itself but great joy at the same time.” (Shearer 2006, 20) She described Horst as a “major-domo throwing cold water on most choreographic projects.” (Shearer 1984, 198) May O’Donnell, who was Horst’s assistant, “remembers the hours she [O’Donnell] spent comforting Sybil.” (qtd in Horwitz, 26)

Horst & Graham in front of Commons c. 1934, Bennington College Archive

Shearer wasn’t crazy about Horst’s outsized devotion to Martha Graham, which she felt had “an enormous influence on the community.” (McPherson, 34) To a friend, she wrote, “This Graham cult is a marvelous thing. I can’t help admiring it, as one does the Catholic Church for its persistence.” (Shearer 2006, 151) Even though she was wowed by Graham’s presence and by her choreography, she had no desire for further study with the high priestess of modern dance: “Miss Graham treats us as though we are morons,” she wrote. “She talks baby talk to us, and I hate to be told that I look like an ‘anxious female’ when I stick my chin out because another part of my anatomy hurts.” (McPherson, 33)

On the faculty, teaching dance criticism and theory, was the New York Times critic John Martin. During Sybil’s third summer, they were sitting at a table in the dining room (perhaps Doris and Charles were there), and he said to the others, “Well I saw Sybil talking to the trees again today.” She replied, “Mister Martin, you are mistaken. I was simply testing the rebound of various branches.” (Shearer 2006, 323) Her own rebound to his remark impressed him, and they embarked on a friendship that lasted until his death in 1985. She always appreciated his support in both conversation and in print. “I could so easily have been crushed by a less imaginative critic,” she wrote as part of her tribute to him in Ballet Review. (Shearer 2006, 319). She compared him to Diaghilev in his ability to be a catalyst for choreographers. (Shearer 1984, 23) She acknowledged that their friendship was controversial because critics and artists were not supposed to be friends. (These days, if there is any perception of conflict of interest, a critic must either step aside or disclose the relationship within the review.)

Possibly Bessie Schönberg’s class, 1934, Bennington College Archive

Sybil thought about grand moments in dance history, for instance Michel Fokine’s 1914 reforms for ballet and what they meant for her own time. She considered romantic and classic styles not as opposites but as ever present modes that any choreographer could draw upon. She felt that ballet, being classic, was necessary for training the natural body, while modern techniques were a matter of style. She viewed modern dancers as secret romantics because their work was personal and they favored serious issues over the trivial. (Shearer 1984, 24)

Ballet Caravan, 1936: Lew Christensen’s “Encounter,” MP+D

Much as she revered Pavlova and Nijinsky, Shearer had no patience for Ballet Caravan, the company that Lincoln Kirstein brought to the Bennington School of the Dance. In July 1936, reacting to Ballet Caravan’s program of works (probably by Eugene Loring, Ruthanna Boris, and Lew Christensen), she wrote:

I went to the ballet Saturday night, and have felt ill ever since—just plain disgust that grew from indifference on first seeing it. It cannot be called art, and therefore cannot be compared with our dance, but it is really not entertaining either because of its depressing influence. It tried to be so light and gay that it became strained, just as a gushing society butterfly becomes strained as she grows old. (Shearer 2006, 154)

Sybil at Bennington in 1935, ph Sidney Bernstein, Bennington College Archive

The stone canyon

In the fall of 1934 Shearer moved to Manhattan, where she continued studying with Humphrey and Weidman. (She preferred Holm, but her father, who had agreed to pay for a year of classes, felt the Academy of Allied Arts, where Humphrey and Weidman taught, was more “practical.” [Horwitz 29]) She was still at a beginner level, but by late November she was chosen to be in Humphrey’s “demonstration group” (apparently an understudy or workshop group).

She also studied acting with Maria Ouspenskaya and helped form a group called Theatre Dance Company that aimed to integrate acting and dancing. John Martin’s wife, Louise, gave them acting lessons. The group, which comprised about seventeen people including Fe Alf, Eleanor King, Bill Bales, George Bockman (Lloyd 240) and Jack Cole (Shearer 2006, 185), performed demonstrations that sometimes included Sybil’s choreography.

Shearer hated New York. She called it a “stone canyon” (Christiansen) and likened its skyscrapers to “prehistoric monsters.” (Within This Thicket DVD) As her longtime dancer Toby Nicholson told me, “She felt it was hard to be creative in New York and she wanted to get out of there as soon as she could.” She had no use for the left-leaning dancers of the New Dance Group, remarking snidely, “The Russian Revolution seemed to fascinate everyone.” (Within This Thicket DVD)

One of her rare pieces about world events, And Prophesy, was unfortunately never filmed. She describes it as “My vision of dancing on the edge of a cliff in a wild storm as Germany marched into France in World War II. In my memory I was running and falling and sliding on the ground again and again as I beat the wind with my arms.” (More on this solo later.)

Dancing with Humphrey-Weidman

Although Shearer was not technically advanced that fall, she harbored a “wild imagining” that she might someday get into the Humphrey-Weidman company. (Shearer 2006, 28) As others observed, she worked very hard, and by the fall of 1935 she was invited to join the demonstration group. By January of 1936, she became a full-fledged member of the company. She assisted Humphrey in her teaching at Allied Arts as well as at Bennington during the summers of 1936 and ’38. This was a peak period for the Humphrey-Weidman company, and Sybil was in the original casts of their most enduring works: New Dance, With My Red Fires, and Passacaglia and Fugue in C Minor. (McDonagh 1976)

Dancer and author Stuart Hodes contributes a story about how hard she worked, as told to him by Bill Bales:

…according to Bill Bales, Weidman had said, “Sybil, your dancing needs to be sharper and more clearly defined”…So Sybil went into a studio for six months and came out dancing sharper than anyone had ever danced before. Then Doris said, “Sybil, your dancing needs to be more lyrical,’ so Sybil went into a studio and came out in six months the most lyrical dancer in the company. (Hodes 36)

Doris Humphrey in “Passacaglia,” 1938, Bennington College Archive

Hard work aside, there was also an economic reason Shearer was asked into the understudy group: the Great Depression. Humphrey had found spots for her better dancers in Broadway musicals, with the understanding that they would help support the company with their earnings. (Shearer 2006, 43) But some of them preferred to keep their Broadway gigs rather than return to the poverty of concert dance.

Shearer waffles in her regard for Humphrey. At first she calls the choreographer a genius; she writes, “It has to me all the glamour of the Russian ballet in Nijinksy.” (Shearer 2006, 31) She describes her as “cool, sensitive to philosophical ideas” but that “she had a will of iron.” (Within This Thicket DVD) In an interview with Dawn Lille (Horwitz), she said, “Watching Doris create was very stimulating. But her point of view was extremely narrow.” (Horwitz 1984)

Charles Weidman 1934, Bennington College Archive

Charles Weidman, in addition to being co-director of Humphrey-Weidman, had his own group of less professional male dancers. Among them was one Gerald Davidson, a charming widower from Cleveland with a 6-year-old daughter. He and Sybil fell in love and became engaged. Her flood of letters to “Jerry” are full of passion as well as outpourings about her artistic life; those letters constitute a good chunk of Within This Thicket, Volume 1 of her autobiography. At a certain point, when she realizes the burden that marriage and sudden motherhood would mean to her dance life, she breaks off their relationship. She never again became romantically involved. As her trusty sound engineer James Cunningham said, “She felt she had to devote her life to art to achieve what she wanted to achieve.” (qtd. in Mauro)

Shearer was a standout member of the Humphrey-Weidman company. José Limón, not yet a member of the group, remembers her in the fourth variation of New Dance: “Shearer exploded brilliantly in all directions like a string of Chinese firecrackers:” (Limón 55)

But Sybil discovered that company life was not for her. “I am one globule in this nebulae called the H-W group,” she wrote. (Shearer 2006, 212) Toward the end of her three-year stint, when she was sick and tired of rehearsing the same dances over and over, she acted out her frustration while performing Humphrey’s New Dance. She recounts an uncharacteristic episode of bad behavior:

I stormed through “New Dance” and variations with such a vengeance that I didn’t care, for the first time in my life, whether I was on or off the beat. I just got there when I could with a violence and a conviction that must have made everyone else look wrong. In the variations I suddenly hated every movement and just improvised wildly. The next morning, when Bill (Bales) said, with his Uncle Dudley air, that I should learn to control my emotions, I picked up a glass of water and dashed its content in his face, feeling sure at the moment that only a physical action would keep him and his dictatorial manner to himself in the future. When he said, wiping himself off furiously, that he didn’t think it a bit funny, I said I didn’t intend to be funny and stalked off. We didn’t speak for two days. (Shearer 2006, 251)

Later in 1938, when Sybil was on leave, she attended a Humphrey-Weidman performance of three works. According to Humphrey’s biographer Marcia B. Siegel, Shearer “electrified everyone by asserting at a company meeting that besides looking shabby and technically uneven, the company lacked conviction.” (Siegel, 180) In a follow-up letter, ostensibly to clarify and to apologize for angering Doris’ protégé, José Limón, she drove her point home, saying that some of the dancers were just putting on a fixed happy face instead of dancing with conviction throughout the whole body. “And conviction is the keynote to the whole thing…You have to love every move you make.” (Shearer 2006, 240-41)

This idea(l) of conviction surfaced later as well. In May 1940 John Martin stated in the New York Times that modern dance, requiring emotional conviction, and ballet, being mainly about aesthetic beauty, were so different that they would never overlap. Shearer strongly disagreed. In a letter to him, she wrote “…it seems to me that only by a combination of these two entities, emotional conviction and esthetic beauty, can we arrive at the real and the highest form of the dance art.” (Shearer 2006, 275)

Working with Agnes de Mille

Agnes de Mille 1932 , ph Paul Tanqueray

To immerse herself in the New York dance world, Shearer attended concerts at Guild Theatre every Sunday (this was before the 92nd Street Y became the bastion of modern dance). One performance that stirred her curiosity was that of budding choreographer Agnes de Mille. Sybil wrote her a letter, Agnes wrote back, and the two became fast friends. They shared a devotion to dance and a wicked sense of humor. (Shearer 1994, 10)

De Mille loved Sybil’s dancing and recognized her “comic genius” (de Mille 245). In her book Dance to the Piper, she described the younger dancer in an almost mystical way:

Physically she presented the asexual aspect of a Renaissance angel, sensitive but not girlish, her face too strong for prettiness, her manner unbroken with the noble ease of an animal or a spirit. She might have stepped from any Botticelli fresco. She had the enigmatic smile, the airy magnificence, the unsexed purity and vigor of his heavenly youths. She was long-waisted and slender, with angelic long arms, hands that played the air like an instrument and the strong printless foot of God’s messengers. She was a visitor in my studio, a visitor in this world, and, serene in dedication, gave herself daily to the beloved work with the absorption and success of a fanatic. (de Mille, 246)

She invited Shearer into her first touring company of only five people. Shearer also served as de Mille’s assistant on two ballets for Ballet Theatre (later ABT): Black Ritual (Obeah), for the opening season in 1940, and Three Virgins and a Devil the following year. For the latter, Sybil helped develop the role of the devil. De Mille writes:

I created the part of the devil on Sybil Shearer, or rather she created it in spite of the laws of nature and contrary to all human experience. Sybil suggested an Hieronymus Bosch animal whirling and scrabbling over the floor. She gave the impression of flapping in midair shoulder height, banging up against the walls like some untidy bat. She could fall over flat, of a piece, like a felled tree, and all the time there was a preoccupation of business in the face, a confused craftiness as if all the wheels of the brain were out of cog and racing separately. She has always had the ability to maintain three or four rhythms in her separate members without regard to what her head was doing. Guests who came to visit us in our den went out stricken and speechless. Sybil could not get up on point which barred her automatically from the company. She was also, of course not male and therefore perhaps not eligible for this role. (De Mille 257)

The role of the Devil eventually went to Eugene Loring and then to Jerome Robbins, who had already gotten noticed in the comedic role of the Youth.

As a dancer, Shearer felt her work with de Mille was more collaborative than with than with Humphrey:

It was much more fun working with her than with Doris and Charles because I, too, was creating, and I admired her attention to detail of expression and meaning as well as her interesting conversation. (Shearer 1994, 11)

Agnes de Mille in “Three Virgins and a Devil,”Ballet Theatre

De Mille liked Shearer’s dancing so much that she wanted her to play “dance Laurey” in Oklahoma! (Nicholson email) (This was the lead dancing role in the famously long—twelve-minute—dream ballet.) But Shearer felt that any immersion in a commercial venture would taint her own work. (Shearer 1994, 11)

Although she admired Shearer’s dancing, de Mille did not think of her as a choreographer. So she was surprised to learn that the younger dancer was planning a solo concert at Carnegie Chamber Music Hall. She asked to see a preview, after which she was stunned. “It became suddenly clear that Sybil had enormous gifts. I sat staring, looking white and, I’m sure, small.” (de Mille, 258)

For her part, Shearer felt that de Mille never came up with original movement but more or less arranged movement in theatrical ways. It was Humphrey whom she looked up to as a choreographer:

When I create I tend to do more what Doris talked about, which is to be oneself. My concept was to experiment with as much abstract movement as possible in order to enlarge my vocabulary, but I also included movement from all walks of life, animal, vegetable, and mineral. (Horwitz, 31)

Some of these explorations produced humorous portrayals. In African Scrontch by Mail, she imagined a housewife learning to jitterbug by correspondence. In In a Vacuum, a factory worker gets so caught up in mechanical actions that she almost becomes a machine. Shearer sees these works as more than just disjointed, limbs-flailing slap-stick. “Actually these satires that I was doing, though funny, were not comedies at all. They were tragicomedies on the human dilemma—Who am I? Why am I here? Where am I going?” (Shearer 2006, 273)

Making her mark

In 1938 Shearer requested time off from both the Humphrey-Weidman company and the dance theater group to delve into her own choreography. As she wrote to Humphrey, she needed time alone so that “I might gain control over my whole body to the point of being capable of any quality of movement which I would wish to use in the expression of an idea.” She also planned, as John Martin had suggested, to take in music concerts, art exhibits, and literature. (The title of one of her first solos, O sleeper of the land of shadows, wake! expand! is from a poem by William Blake.)

Screen grab from “In a Vacuum,” CFA

For her debut solo concert at Carnegie Chamber Music Hall in October 1941, she created a range of moods, from the mystical Nocturne to the explosive And Prophesy to the agitated In a Vacuum.

Walter Terry in the Herald Tribune proclaimed In a Vacuum “one of the funniest things I’ve ever seen.” Sybil had actually gotten advance notice of his reaction when Agnes came running backstage, blurting out, “Did you hear that huge guffaw during In a Vacuum? That was the Herald Tribune!” (Shearer 2006, 297)

Terry also wrote that And Prophesy “was flooded with dynamic energy to the point of explosion.” (Shearer 2006, 334) He was so excited by the whole concert that he devoted his Sunday column, four days later, to it. He compared her concert favorably to Massine’s latest premiere for the Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo, which he slammed. (qtd. in Shearer 2006, 336)

Shearer at Jacob’s Pillow 1942, ph John Lindquist © Harvard Theatre Collection

John Martin wrote a positive review, noting some flaws, but saying that And Prophesy “achieves a tinge of creative madness.” He concluded with “Through it all gleams the light of a definite and an original talent.” (qtd. in Shearer 2006, 335)

The good reviews established Shearer as an artist on the rise, and the New York Times named her the season’s best solo debut (John Martin being the sole arbiter of that accolade). She was invited to appear on a program of young dance artists on the first summer of the Jacob’s Pillow Dance Festival, 1942.

Moving westward

Fortified by good notices, Shearer felt she could leave New York without damaging her currency as a dance maker. Accepting a position at Roosevelt College (now Roosevelt University), she moved to the Chicago suburbs in 1942. There she met Helen Balfour Morrison, a noted portrait artist twelve years her senior. Morrison believed in Shearer so much that she became her lighting designer, photographer, publicist, and all around encourager.

Shearer was able to really concentrate on making dances, sometimes getting to the depths of humanity in a way that touched people. Margaret Lloyd, dance critic for the Christian Science Monitor, wrote about her in her 1949 book, The Borzoi Book of Modern Dance, the first critical collection about modern dance:

In “No Peace on Earth” (Scriabin), the stooped figure of an old woman wrapped in the gray of sackcloth and ashes, painfully crawls across the stage, her hands clasping and unclasping in commingled agony and prayer. It is very short, and poignant, for it is a concentrate of misery. Sybil can use her hands with Oriental fluency. She can do anything with her body. She can liquify it to the point of dissolution, or coil it taut as a steel spring, only to let go in lashes of energy. She can practically turn herself inside out with convulsive movements, or flow with the placidity of a sunlit stream. From the molecular to the largest muscular areas, every fiber, tendon, and tissue is hers to command. The news should be withheld no longer—she is a remarkable dancer. (Lloyd 236)

Another critic who appreciated Shearer was Jill Johnston—the crazily brilliant writer who championed Judson Dance Theater in the early sixties. In a pre-Judson essay, she paired Shearer with Katherine Litz as two dancers who harked backed to Isadora:

In some sense the style of Shearer and Litz was a return to the romanticism of Isadora Duncan. It was definitely a reaction to the tortured introversion of Graham, and to the broad, open extroversion of Humphrey, and to the techniques of both, which were sharp, angular and dissonant. Yet, unlike Duncan, their romanticism is refined and distilled by its formal containment and by the concentrated internalization of gestures. The art of Shearer and Litz is a solo art. Although they have both choreographed for groups, they were never interested in the massive, symphonic forms that were so popular in the thirties. (Johnston 164)

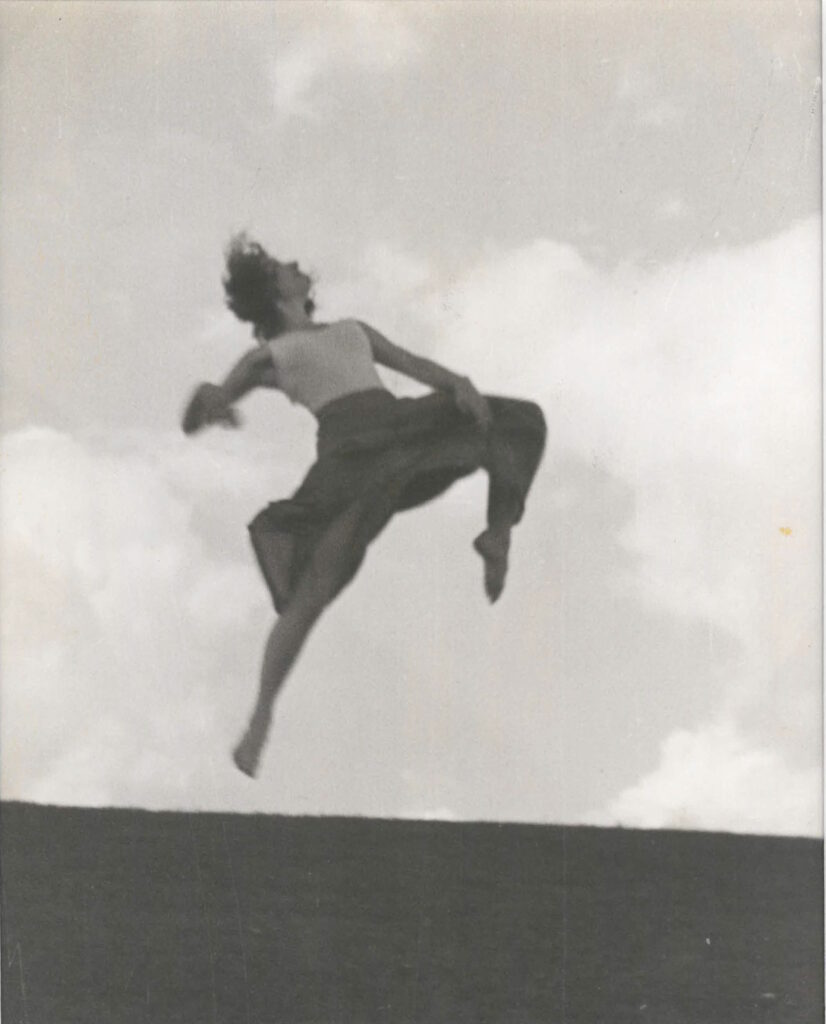

In Northbrook, Morrison-Shearer Foundation

When asked what she had in common with Isadora Duncan, Shearer pointed to music. Isadora “was music,” she said. She claimed that Dalcroze, who was an influence on Mary Wigman and Marie Rambert (and, I would add, Michio Ito), had been blown away by Duncan’s musicality. Like Duncan, Shearer danced to the classical composers Chopin, Brahms, Schubert, Bach, Beethoven, and Scriabin. But she also sought contemporary composers like Bela Bartok, Henry Brant, Gunther Schuller, Kurt Weill, and Gyorgi Ligeti—and she was one of the first modern dancers to use jazz music. For her Salute to Old Friends suite, she chose recordings by Miles Davis, Dave Brubeck, Benny Goodman, and W. C. Handy. (Note: Another way she was different from Duncan is that she believed in ballet training as a foundation for any kind of dancing.)

Like Isadora too, she reveled in the open air. In this film of Early Northbrook excerpts, she is dancing with the wind. (I suggest going 45 seconds in.) Famous for her elusiveness, she described her efforts to choreograph as wanting to “put my hands around the unknown.” (interview with Walter Terry)

Perhaps the most obvious tribute to the “unknown” is her 1949 solo Mysterium Tremendum, danced to Benjamin Britten’s “Ceremony of Carols.” She moves as though blown by a slow breeze or a quick wind—or by the prayer within Britten’s music.

Sybil helping to build studio 1952, ph Helen Morrison, Morrison-Shearer Foundation.

In 1951 she moved to Northbrook, a suburb of Chicago, where she bought land from Morrison. On an acre of tree-studded land, Morrison designed a secluded studio/home for her. At the center of the building was the large, mirror-less studio, with one entire side a window looking out onto the garden. The walls were flexible, and the lighting could be adjusted for rehearsal showings or filmings. Since she refused to be filmed onstage, Shearer, with the help of Morrison, figured out how to record her dancing in this studio with optimal lighting. [Aside: Although the films constitute a terrific archive, to my eye, they do not capture the electric sensation of seeing her onstage.]

Sybil in Northbrook Studio, Morrison-Shearer Foundation

John Martin was of two minds about Shearer’s choice to leave New York. In 1959 he wrote,

She is extremely independent, sometimes infuriatingly so…That she is a mystic, a nature mystic, goes without saying, and this is the core of her power…More honor to Miss Shearer for her sense of values. May she retain her deaf ear to the siren’s song of the Capital of the Dance World.” (Martin, “The Dance: Forward,” 11/1/59)

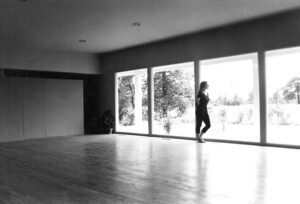

Program notes for solo performance at BAM, 1954, BAM Hamm Archives

She gave her last New York performance at the Brooklyn Academy of Music in 1954. The dance artist Martha Wittman, then a first-year student at Juilliard, remembers one of the sections of the eleven numbered pieces:

I think it may have been to a Scarlatti piece—a quick section. I remember the movements being swift, darting. She was in darkish blue leotard and tights—not a dress—with small pieces/scraps of white material, featherlike, that floated away from her body in the breezes as she moved so quickly. I believe she was often also perched on half toe. It all reminded me of a bird. (Wittman email)

In 1957 Shearer approached the Dance Panel of the U. S. State Department, which made the decisions on which dance artists and companies to send abroad. The Panel members included Martha Hill, Lincoln Kirstein, Walter Terry, Ann Barzel, and Margaret Lloyd. (Two years earlier, when Lloyd had suggested Merce Cunningham and John Cage, the recorded minutes revealed that “The Panel considers Harry Partch even more contemporary and avant-garde than Cage, and Sybil Shearer better than Merce Cunningham, if we want to send this type of performer.” [Prevots 55]) When Sybil herself applied, the response was not exactly enthusiastic: “Although she is a marvelous dancer, as a performer she is unpredictable. And audiences often do not understand what she is doing.” (Prevots 61)

John Martin expressed this confused feeling of her audience when he wrote that “You go with an open mind, and you come away either sputtering or walking on air.” (Martin 1953)

Another aspect of her unpredictability was recounted by Naomi Jackson, historian of dance at the 92nd Street Y. About Shearer’s performances, she wrote, “If she did not like the ambiance of a particular audience, she would leave the stage and end the performance.” (Jackson 160)

(Her quixotic behavior was repeated in 1967—with an inadvertently historic outcome—when Shearer cancelled her appearance at the Hunter College Playhouse on short notice. Luckily the Playhouse director learned that Anna Halprin was available to fill the spot. [Ross 192] Thus New York was treated to Parades and Changes, momentous as a performance of imagistic postmodernism and notorious for earning Halprin’s company a warrant for their arrest because of the [understated, ritualistic] nudity. Tales of this performance reverberated through the decades so resoundingly that it was celebrated fifty years later.)

Another quality that may have bothered the Dance Panel: Shearer eschewed all presentational niceties. Chicago critic Joseph Houseal wrote, “Sybil was a joyous creature, but she was anti-establishment to the core and social mores were meaningless to her.” (Houseal, 11) Also meaningless to her were the trappings of theatricality: She never wore stage make-up or changed her hair. As Martin noted in 1946, her “costuming as well as her personal grooming tend toward the drab.” (Martin 1946) Jackson’s view was that Shearer was “confrontational in her challenge of the dance world.” (Jackson, 160)

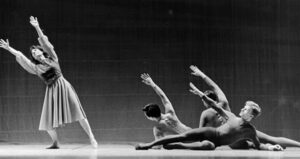

Within this Thicket 1959, Shearer with Masao Yoshimasu and Toby Nicholson, Morrison-Shearer Foundation

In 1958 Shearer started choreographing on her advanced students, possibly because of the critics’ growing negativity toward her solos. Her group works mingled legible gestures with dance movement. The Reflection in the Puddle Is Mine has a whiff of the enigmatic quality of her solos.

In 1962 Shearer was appointed artist-in-residence of the National College of Education (now National Louis University) in Evanston, Illinois. Her company often held its annual program at the school’s Arnold Theater. She hired a Cecchetti ballet teacher, Lee Wallace, to give the warmups. She liked Cecchetti because she felt it didn’t impose a style onto the steps. (Nicholson email, Aug. 19, 2021) After 1972, when they gave their last performance at Chicago’s Arie Crown Theater, Sybil worked with Helen Morrison to make films of her dance pieces. They shot their main film collaboration, A Sheaf of Dreams, outdoors in changing seasons. Ann Barzel, writing in Dance Magazine, called the film “a poem of visual images”:

“A Sheaf of Dreams,” ph Helen Morrison, Morrison-Shearer Foundation

Memories are as trivial as plucking a flower in spring, as darkly significant as the volatile dance paralleled by storm clouds, or as elusive as a shadow glimpsed in a pool. There are bits of…beautiful dancing, by Sybil Shearer, at her best in an environment of nature. (Barzel, 16)

Meanwhile, the Sybil Shearer School of Dance expanded to nine branches in cities like Evanston, Lake Forest, Northbrook, and Milwaukee. On Saturdays in Winnetka, she trained teachers for these schools. Every December she produced a program called Christmas Wish, with about 300 children gathered from the various schools. Eventually, in order to concentrate on her company, she put each school in the charge of a teacher she had trained. So, for instance, the Winnetka school became the Toby Nicholson School of Dance.(Nicholson, email Aug. 17)

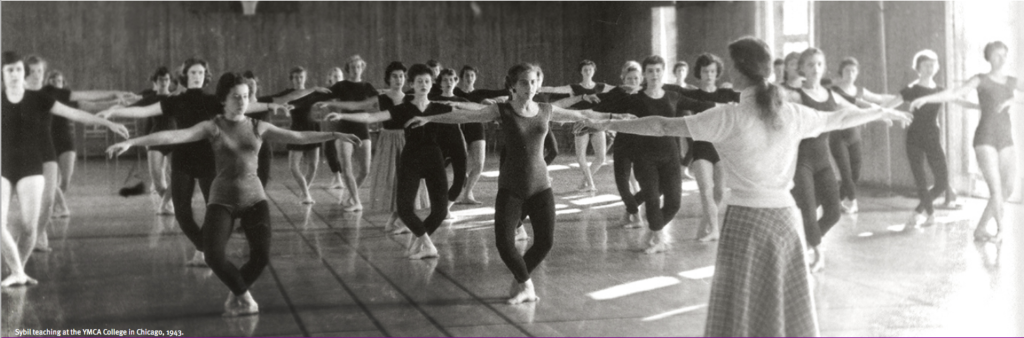

Shearer teaching at YMCA College of Chicago 1943, Morrison-Shearer Foundation.

A downward slide, critically speaking

Amid the raves of 1941, John Martin had slipped in one caution: “Sentimentality constitutes Miss Shearer’s greatest peril. She creates too much in the over-lyrical vein of the recital dancing of fifteen years ago to be considered a mature artist at the moment.” (qtd. in Shearer 2006, 335) It is perhaps ironic that Shearer herself had already articulated the danger of sentimentality in 1934: “It is a kind of self-expression without form. It is all right…in the private life of an individual, but not all right in public because it is formless and artless.” (qtd in McPherson 38)]

Solo from “Shades Before Mars,” 1953, ph Helen Morrison, Morrison-Shearer Foundation

By the mid-40s Martin’s reviews still glowed but also imparted a vague sense that she wasn’t fulfilling her potential, that perhaps the peril he had named had invaded. In 1951, with her suite of fanciful characters, Once Upon a Time, he felt she had fallen “into the realm of pure personal indulgence” and that this was “a sad occasion.” (qtd. in Horwitz, 28. Original quote in NYT June 19, 1951) (However some critics found it enchanting, and Don McDonagh praised it for its “exceptional gestural elegance.” [McDonagh 1976, 309].)

Her 1949 appearance at Carnegie Hall garnered a bewildered review from Nik Krevitsky in Dance Observer (Louis Horst’s publication). The program had the look of a casual rehearsal. He ended by saying, “There was an arrogance in this studied naivete of the April 24th concert that shows no sign of progress in one of our most distinguished young dancers.” (Krevitsky 83)

Her 1949 appearance at Carnegie Hall garnered a bewildered review from Nik Krevitsky in Dance Observer (Louis Horst’s publication). The program had the look of a casual rehearsal. He ended by saying, “There was an arrogance in this studied naivete of the April 24th concert that shows no sign of progress in one of our most distinguished young dancers.” (Krevitsky 83)

Shearer’s contribution to the 1959 edition of American Dance Festival brought her down even lower in the eyes of critics. That summer was a tribute to Doris Humphrey, who had died the previous December, and guest artists included José Limón, Pauline Koner, Merce Cunningham, Ruth Currier, Daniel Nagrin, Helen Tamiris, and Sybil Shearer. (Anderson 74) According to Jack Anderson, many critics were disappointed by Shearer’s dances, which shared a program with Cunningham and Pauline Koner. Even Margaret Lloyd, who had championed Shearer, wrote a stinging review in the Christian Science Monitor:

Noted for range of movement and loftiness of thought, she astonished everybody by descending from her accustomed heights to indulge in sweet and pretty stepping with Dalcroze effects. It was as if some philosopher of reputed profundity (and rather careless in dress) had come out on the lecture platform to chatter about trivialities. (qtd in Anderson 75-76)

In Dance Magazine, Doris Hering contrasted Shearer’s growth to that of Cunningham, adding a special note of condemnation:

Both are mystics. Both move as though as though chosen by the wind. But Miss Shearer’s artistic development has not been nearly so constant as that of Mr. Cunningham—not so cumulative in its sophistication. And at the present time she seems to be out of contact not only with her audience, but with herself.” (qtd in Anderson 76, originally Oct. 1959, 35)

“All is not gold, but almost,” 1961 ph Helen Morrison, Morrison-Shearer Foundation

In December of that year, Martin traveled to Winnetka yet again to see her performance and gave a hot and cold review. He deemed the first half, Within This Thicket, to Bartok, to be “intensely personal and yet somehow subcutaneously communicative,” resulting in a work of “tremendous power and beauty.” About the second half, where she resorted to ballet steps, he wrote, “The result is sterile, largely negating her great and individual powers of creative movement.” (Martin 1959)

Don McDonagh, who had proclaimed Shearer to be ahead of her time in her internal, non-linear concerns (McDonagh 1970, 37), now felt that her visits to New York drew a decidedly mixed response: “She began to be regarded as a slightly dotty favorite aunt with a formidable technique who was liable to do anything on stage. She was odd and unpredictable and was held in baffled affection.” (McDonagh 1970, 38)

Still, she kept dancing to her own drum. And in a 1963 review, John Martin seemed to have recovered his good cheer and wrote that “her movement continues to be supremely personal, and her turn of mind incurably inquisitive so that she is forever evolving fresh and evocative material.” (Martin, 1963)

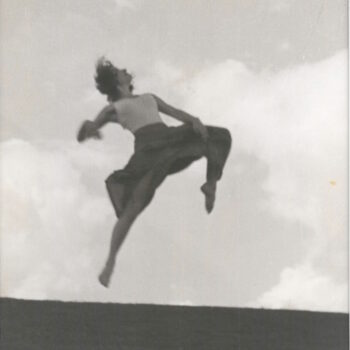

Sybil leaping, ph Helen Morrison, Morrison-Shearer Foundation

One example of a fresh approach was reported by Russell Hartley in Dance Magazine. He describes a 1968 performance in Berkeley where she interpreted the styles of famous painters like Picasso and Renoir. Then she asked for the audience to call out names of other painters, and she embodied each style on the spot, with uncanny accuracy, to hear it from Hartley. (Hartley 105-07)

The Neumeier connection

John Neumeier 1961, Morrison-Shearer Foundation

One of Shearer’s dancers was to become a major international figure: John Neumeier. As a student at Marquette University in Milwaukee in the 60s, he commuted to Chicago two or three times a week to study and rehearse with her—for no pay. They shared a passion for dance history. He already knew about Nijinsky as a dancer, but his interest in this icon leapt forward when he met Shearer. “What I remember most was Sybil’s clearly analyzed, lucid explanation of Vaslav Nijinsky’s great importance as a choreographer of the twentieth century.” (Neumeier xi) Neumeier, who has been the choreographer and artistic director of Hamburg Ballet for almost fifty years, has been famously obsessed with Nijinsky. His Foundation John Neumeier now possesses the largest collection of Nijinsky drawings and artifacts in the world.)

More than their shared interest in Nijinsky, Sybil was a model and mentor as a dance artist. In 2013, he called her “my greatest inspiration.” (Smith) In a recent interview with Jenai Cutcher of the Chicago Dance History Project, Neumeier said,

She was a true genius, being so inventive, so special … There were two things: she was the first person who could make me laugh without there being a story. It was through the physicality of her body that she gave us a moment of human understanding of ourselves, a flash of our….stupidity, what is funny about us. And a very modern idea of lyricism— lyricism, not as being fairy light, but the lyricism of the earth. The weight of her movement was unforgettable. (CDHP interview)

John Neumeier, in Hamburg, being interviewed by Chicago Dance History Project, 2020

He later repeated this idea, using the phrase “the heaviness of lyricism” (which, one might say, is the quality of his work that is beloved in Germany). Then he added, “But also a sense of inner concentration…out of which movement comes as opposed to performance.”

But he also recalled how frustrating her rehearsals could be:

One day we’d be doing something that had to do with Brueghel, the next day some kind of Bartok. So we never knew what we were doing or if there was a kind of goal. But because of her palpable genius, it was important to be near her, to watch her. (CDHP)

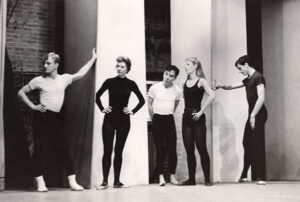

“Within This Thicket,” with Nicholson at left and Neumeier at right

One day, while rehearsing Time Longs for Eternity from her suite “Fables and Proverbs,” Shearer lost her temper. The provocation was that Neumeier had changed a horizontal arabesque into a more upright, balletic arabesque. “We were in the theater in Winnetka and I was doing this thing and she screamed at me and ran out of the theater. I didn’t understand exactly what was happening.” When she calmed down, she explained to him that, for her, a horizontal line symbolized eternity and he was ruining the symbolism of the ballet. Apparently she cried and embraced him, saying, “John I hope this works.”

Decades later, he wrote that “I was sorry and upset, but also surprised and somehow moved by her showing her emotions so openly.” (Neumeier xiii) Ironically, he ended up using the same imagery—a horizontal line to represent eternity—in his own choreography.

(This clip of a rehearsal of The Reflection in the Puddle Is Mine begins with Neumeier sitting on Nicholson’s back.)

She was writing all along

When Helen Morrison became deathly ill in 1984, she urged Shearer to write about dance. The dancer followed her advice, as usual. She had long ago accepted Morrison as a mentor because she felt “Helen’s concept of wholeness was unique in this departmental world.” (Shearer 2012, 475) Sybil had always written letters, for keeps—meaning, she hand-wrote them into her notebook, then copied them on paper to send to their destinations. So the first draft was in some way already a memoir.

Threaded through her columns in Ballet Review (which sadly folded in 2020) are hints of her artistic ideals. Her critiques were always conscious of “unseen elements.” In an interview with Walter Terry, she said, “I often think that when you look at a dancer, you’re seeing the unseen, and that’s what always interest me, as I look to see…where I can join with them and go somewhere else.” (Terry interview 1980)

The Inheritance, photo series, Morrison-Shearer Foundation.

As the Chicago correspondent for Ballet Review, she reviewed a range of subjects including American Ballet Theatre, Stephen Petronio, Joe Goode, Merce Cunningham, Hubbard Street, Twyla Tharp, the Joffrey Ballet, Baryshnikov’s PastForward, David Dorfman, John Neumeier’s Hamburg Ballet (of course), and Susanne Linke’s reconstructions of German expressionist dances.

She had startling insights that could sometimes be quite harsh. She wrote that “Mark Morris seems to be a choreographer who cages his dancer, then stands back to see how they react.” (Shearer, Spring 1991, 11) Right after Martha Graham’s death, she wrote, “…this group of dancers, left over after her death, should dedicate themselves to recording her works, then put them in a vault…to be revived after…a hundred and fifty years, for a new audience and new dancers.” (Shearer, Winter, 1991, 10)

When she was drawn to a particular dancer, for instance Sally Rousse, Maria Terezia Balogh, Krista Swenson, or Ginger Gillespie, she described them beautifully, ineffably. Occasionally her description of a dancer sounded a lot like her own dance ideals. About Linda-Denise Evans she wrote this: “She captured what in life is only native to dragonflies and hummingbirds, something beyond the control of muscles and balance, an inner essential understanding of what lies within the atmosphere in which she moved…..” (Shearer, Winter 1991, 9)

The curious Sybil/Merce friendship

Merce Cunningham, Jacob’s Pillow 1955. Photo by John Lindquist © Harvard Theatre Collection

Shearer had befriended Cunningham, who had arrived in New York in 1939. In 1949, she and Morrison organized a series of performances at Winnetka’s North Shore County Day Theatre, and one of their first offerings was Merce Cunningham and John Cage. In Volume II of her autobiography, Sybil wrote, “I got these two to come out to the Midwest from New York by telling Merce I would choreograph a dance for him.” (Shearer 2012, 155) When I read this, I had to remember that Merce and Sybil had both been thrust into the category of leading avant-gardists. When did she make this solo for him? The day before his performance. She wanted to see all his other solos before deciding on movement that would contrast nicely. And then, even more strangely—and possibly unethically—she reviewed the program in Dance News. Although she did say in the review that she choreographed one of the solos, she did not say that she and Morrison produced the program. [Note: She didn’t begin her writing career until 1984, so I’m guessing that she wrote it because she felt it wouldn’t be covered any other way.] Ethical questions aside, she made perceptive comments:

One has to transport oneself into Cunningham’s world as though you were listening to the language of the animals or the insects….”Root of an Unfocus” was a high point emotionally, and I felt chills of repulsion and attraction mounting and tacking until I wanted to get in there and dance too….But in “Mysterious Adventure” we were drawn into the warm hypnotic flow and were carried on and on way past the end of the performance. (Shearer 1949)

The solo she made for him, Scribble Scrabble (or A Woman’s Version of a Man’s World), was never performed again. (Vaughan 49; Shearer 2012, 155) But Merce remained fond of Sybil. According to Bonnie Brooks, a Chicago presenter and longtime friend of Cunningham, “Whenever he came to Chicago, one of the first things Merce would always ask me was ‘Is Sybil coming?’ He had great admiration for her.” (email, Aug. 11, 2021).

In later years, that admiration was no longer mutual. In a 2000 review in Ballet Review, she slammed him. She claimed that his choreography “while suggesting movement, actually put movement to sleep…what emerged seemed to be punctuation without connecting to words…a kind of modern puritanism in leotards…statically stylized…Cunningham now has almost erased movement from his choreography by using dancers who are muscular but static …these performers look like gymnasts who have used machines to train their bodies.” (Shearer 2000, 7) Granted, his dancers became more detached from him as the years went on, and her focus as a critic was more on whether the dancers fully embodied the movement (aka had conviction) than on choreography. But her assessment seems rather harsh.

Getting into Sybil’s skin

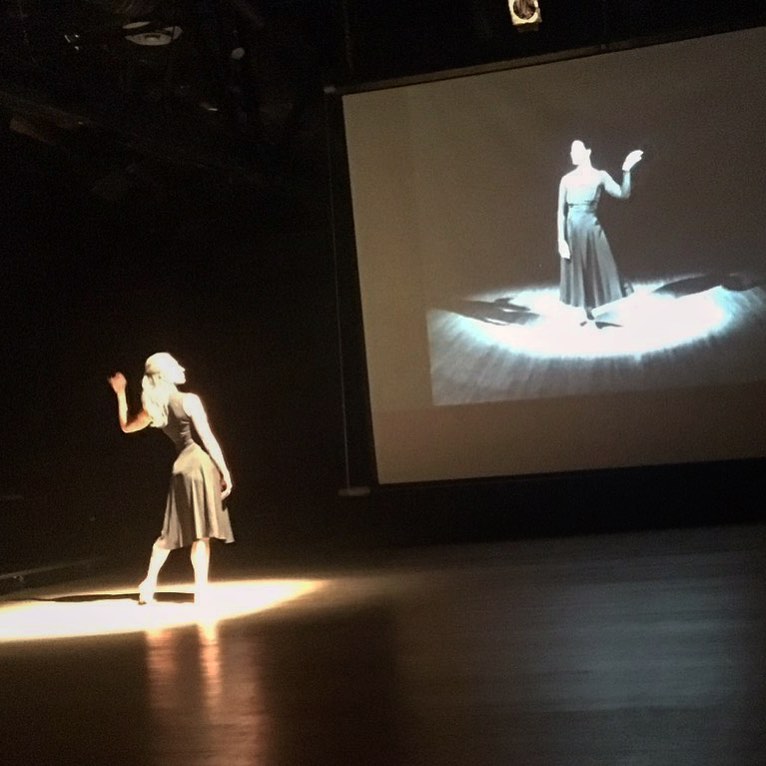

Kristina Isabelle with film of Shearer

The most recent person to re-stage some of Shearer’s dances is Kristina Isabelle, who danced with Bebe Miller and Stephen Petronio in New York. Like Shearer, Isabelle left New York and moved to the Midwest. She has recently steeped herself in what she calls “Sybil work.” She left New York in 2001 because, she says, “I wanted to be in nature and I wanted to make my own movement. And I felt those similarities to Sybil.” She used Shearer’s movement vocabulary as a wedge between her own habits and something new. In this video, you can see Isabelle getting attuned to the outdoors around Sybil’s Northbrook studio and working with her dancers on a piece inspired by Shearer’s choreography.

This work took Isabelle further along in her own choreographic process: “I also wanted to mess myself up, to get someone else’s quirks, see if her rhythm patterns would shift my choices and how that could expand my own movement vocabulary.” She used films of Shearer as a ghostly partner in a new work for her company called And the Spirit Moved Me in 2016. “We would improvise a lot on fire, earth, air and water because she is all of those things… Sometimes earth at the bottom and air or fire at the top, it looks like that within her.” (phone interview Aug. 7, 2021)

Joseph Houseal wrote about Isabelle’s reconstruction of Judgment Seeks Its Own Level in Ballet Review: “The movements are … always surprising with the wave-capped revelation of complex composition arising again and again. The composition is delightfully concealed in the madness.” He went on to say that “Isabelle is the next generation catching the spark from artistic intuition.” (Houseal, 10)

Legacy

As Bonnie Brooks put it, Shearer’s legacy is the “curiosity she stirred among other artists, with her dancing and with her writing and in her unwavering sense of direction in following her own path.” (email Aug. 11, 2021) In more measurable terms, Shearer left behind a five-part legacy, most of which was made possible by Helen Morrison.

First: The films and photographs by Helen Morrison. According to scholar Lizzie Leopold, who helped catalog these holdings, there are nearly 900 films of solos, group works, and Shearer just hanging out with her beloved dogs. (Leopold) As of 2020, these have been transferred to Chicago Film Archives, which now holds the rights.

Ella Rosewood in “Eiight Dance MashUp,” ph Liz Schneider-Cohen, 92 Y

Second: In the last decade, the Morrison-Shearer Foundation has commissioned several re-stagings of Shearer’s works. Jan Bartoszek and Hedwig Dances revived two major ensemble works by Shearer: The Reflection in the Puddle Is Mine and Time Longs for Eternity. Thodos Dance Chicago performed a version of the latter and excerpts of Salute to Old Friends (including the sections on Walter Terry and Agnes De Mille but not the ones on John Martin and Doris Humphrey). In this preview video from 2014, Melissa Thodos and Toby Nicholson, now a trustee of the Morrison-Shearer Foundation, explain a bit about these works. In New York, Ella Rosewood, a dance artist who has reconstructed early modern dance works, created a mashup of herself and a film of Shearer in Eighth Dance (Mussorgsky). As mentioned above, Kristina Isabelle is the latest to challenge herself in this way.

Third: The longevity of Neumeier as a choreographic force in Germany, where he has led Hamburg Ballet for almost 50 years. In June 1984, when Hamburg Ballet came to Ravinia, Sybil was thrilled with the choreography, dancing, and spirituality, as reflected in her review. Completely up front about her mentoring relationship to him, she reported her post-performance conversation with him:

Hamburg Ballet in Bach’s Saint Matthew Passion, 1984, Ravinia Festival/Jacqueline Durand

Later John said to me, “You saw yourself in my work,” and I said, “Yes.” And he said, “I did not try to copy you, but the way you thought and constructed choreography became a part of me, and I found that as I began to work you were there with me.” Because he is highly intellectual and a thinking man he could see this, and because he is a highly intuitive artist he could feel this, and because he is highly moral he could acknowledge this. And I feel fulfilled to have progeny who understand me and what I have always wanted for dance.” (Shearer 1984, 40)

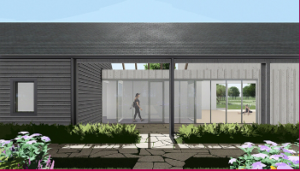

Sybil Shearer Studio at Ragdale (rendering)

Fourth: Looking to the future, the Morrison-Shearer Foundation has partnered with The Ragdale Foundation, an artist residency program, to create a new studio. The Sybil Shearer Studio in Lake Forest will house both a dance studio and a composer’s work space to be part of Ragdale’s residency programs. An echo of the Northbrook studio, the Ragdale studio will have wide windows so dancers can look out onto nature.

Fifth: Her legacy also includes the many probing, questioning, subjective, poetic reviews she wrote in Ballet Review and the three volumes of Without Wings the Way Is Steep. It was Helen Morrison who had encouraged Shearer to write dance criticism and to write her autobiography, which Sybil started at age 82.

I leave you with some choice pearls from her writings:

• “…movement is that force out of which everything has been created. It is a step toward rediscovering spiritual sight, which has been lost for so many centuries in the gradual erosion of the spiritual world.” (Shearer, Summer 2000, 7)

• “A performance for me was a complete emptying out, and after each one I had to have time to recuperate. I needed to withdraw between performances in order that I would have the full amount to give the next time.” (Shearer 2006, xvi)

• “Real freedom is the ability to become the “other,” when seeming opposites merge or when life and death coalesce into love. Then, anything in the universe is possible.” (Shearer, Summer 2000, 10)

• “In dreams there is a logical illogic, which is the usual prerogative of most good art—a discovery of the unknown that emerges and then recedes again.” (Shearer Winter 1998, 5)

“Ondine,” 1953, ph Helen Morrison. Morrison-Shearer Foundation.

• “As far as I am concerned, there are three sides of things: the dramatic, the comic, and the lyric. The lyric is the wholeness; the dramatic and the comic are just subtraction from the whole. The lyricism is everything, it’s the giving and the taking, and that is all of life. It’s a balance — a balance of tension and relaxation, which is the balance between taking and giving.” (Horwitz, 32)

• “Almost everything is a living thing before it becomes inert… A room is simply filled with all the people who were ever in there. And that’s what I feel choreography is: you make a choice from all the movements that are surrounding you.” (qtd. in Horwitz, 32)

• “The arts can be meaningful or decorative, but even decoration has social responsibility.” (Shearer, Spring 1991,12)

• “…purification thru movement (eliminating protest without losing strength), is one of the questions for the future of the dance as an art for all of humanity.” (Shearer, Spring 1997, 17)

Portrait of Sybil by Helen Morrison for the Jan. 1950 issue of Dance Magazine

• “What I believe to be important is not subject matter of the past, nor subject matter of today, nor subject matter of the future, but any material used at any time, romantic or classic, that will reflect the nobility of the spirit and produce a work of art.” (Shearer 1984, 25)

¶¶¶

Special thanks to Scott Lundius and Toby Nicholson of the Morrison-Shearer Foundation, Kristina Isabelle, Lizzie Leopold, Bonnie Brooks, Nick Panfil at Ravinia, Norton Owen at Jacob’s Pillow, Meryl Wheeler at the 92nd Street Y, Martha Wittman, Lynn Colburn Shapiro, Hedy Weiss, Michelle Boulé, Sharon Lehner at BAM Archives, and Dean Jeffrey of ADF Archives. Also, thanks to the staff people at Juilliard’s Lila Acheson Wallace Library, the Bennington Digital Archive, and the Jerome Robbins Dance Division at NY Public Library for the Performing Arts.

Sources

Books

Anderson, Jack. The American Dance Festival. Duke University Press, 1987.

De Mille, Agnes. Dance to the Piper. New York Review Books, 1951, 2015.

Jackson, Naomi. Converging Movements: Modern Dance and Jewish Culture at the 92nd Street Y. Wesleyan University Press, 2000.

Limón, José. An Unfinished Memoir. Lynn Garafola, ed. Wesleyan University Press, 1999.

Lloyd, Margaret. The Borzoi Book of Modern Dance. Alfred A. Knopf, 1949. “New Leaders: Sybil Shearer,” pp. 232–243.

Martin, John. John Martin’s Book of the Dance. Tudor Publishing Company, 1963.

McDonagh, Don. The Rise and Fall and Rise of Modern Dance. Outerbridge & Dienstfrey, 1970.

———. Don McDonagh’s Complete Guide to Modern Dance. Popular Library 1977. Doubleday, 1976.

McPherson, Elizabeth, ed. The Bennington School of the Dance: A History of Writings and Interviews. McFarland, 2013.

Prevots, Naima. Dance for Export: Cultural Diplomacy and the Cold War, Wesleyan University Press, 1998.

Ross, Janice. Anna Halprin: Experience as Dance. University of California Press, 2007.

Shearer, Sybil. Without Wings the Way Is Steep, the Autobiography of Sybil Shearer, Volume I: Within This Thicket, Morris-Shearer Foundation, 2006.

———Volume II, The Midwest Inheritance, 2012.

Siegel, Marcia B. Days on Earth: The Dance of Doris Humphrey. Yale University Press, 1987.

Sorell, Walter. The Dance Through the Ages. Grosset & Dunlap 1967.

Terry, Walter. The Dance in America. Revised edition. Harper Colophon Books 1971. Harper & Rowe, 1956.

Articles

Anderson, Jack. “Sybil Shearer, 93, Dancer of the Spiritual and Human, Dies.” New York Times, Nov. 23, 2005.

Barzel, Ann. “News from Chicago.” Dance Magazine, July 1976.

Christiansen, Richard.“Sybil Shearer: An Original in Every Way,” Chicago Tribune, Sept. 19, 1993.

Hartley, Russell. “San Francisco Bay Area News.” Dance Magazine, March 1968, pp. 105-06.

Houseal, Joseph. Ballet Review, Summer 2017.

Horwitz, Dawn Lille. “A Conversation with Sybil Shearer.” Ballet Review, Fall 1984 pp. 26–35. [Note: This writer is now known simply as Dawn Lille.]

Isaacs, Deanna. “Sybil Shearer Tribute.” The Chicago Reader, Feb. 2, 2006.

Johnston, Jill. “The New American Modern Dance.” Salmagundi, Spring-Summer 1976, pp. 149-174

Krevitsky, Nik. “Reviews of the Month: Sybil Shearer.” Dance Observer, June/July 1949.

Leopold, Lizzie. “Sybil Shearer: An Archive in Motion,” forthcoming in Dancing on the Third Coast: Chicago Dance Histories, eds. Susan Manning and Lizzie Leopold, University of Illinois Press, 2023.

Martin, John, reviews in the New York Times, 1941, 1946, 1949, 1951, 1959, 1963.

———. Feature story: “The Dance: New Ways: Two Artists Show Fruits of Creative Solitude,” New York Times, Nov. 8, 1953.

———. Feature story: “Maverick of the Midwest,” Way off Broadway, New York Times, Nov. 1, 1959.

Mauro, Lucia. “Swan Song.” Chicago Mag, June 25, 2007.

Molzahn, Laura ‘ Chicago Inspired’ from Thodos Dance Chicago, Chicago Tribune, Feb. 22, 2015.

Neumeier, John. “Foreword” to Without Wings the Way Is Steep, Vol. II: The Midwest Inheritance. Morris-Shearer Foundation, 2012.

Shearer, Sybil. Dance News, March, 1949.

———. “Looking Back.” Ballet Review, Fall 1984.

———. “Agnes de Mille.” Ballet Review, Winter 1994.

———. As Chicago correspondent for Ballet Review: Spring 1986, Spring 1989, Summer 1988, Spring 1991, Summer 1991, Spring 1997, Summer 1997, Winter 1998, Summer 2000.

Smith, Sid. “Hamburg Ballet brings ‘Nijinsky’ home.” Chicago Tribune, Jan. 25, 2013

Other

Neumeier, John. Video interview with Jenai Cutcher. January 14, 2020. Chicago Dance History Project (CDHP)

Sybil Shearer interviewed by Walter Terry. Chicago Film Archives, 1980.

Phone with Kristina Isabelle, Aug. 7, 2021

The Newberry Archives: Choreography and the Archives: Preservation, Tradition, and Innovation from Sybil Shearer through the Present.

Unsung Heroes of Dance History 7