Dance Was Everywhere: The Uncredited Spirit of the Harlem Renaissance

This essay of mine was published in Dance Index, Volume 14, Number 1, Summer of 2023. Unfortunately Dance Index, which had its first run from 1942 to 1948 and was resuscitated by Peter Kayafas in 2017, just announced its second “exit.” I cherish both eras of this publication, as every issue contributed to our knowledge of dance history. Another reason I am posting this now is that a new exhibit at the NY Historical Society called The Gay Harlem Renaissance just opened, with George Chauncey (whom I quote below) as chief historian.

ALTHOUGH DANCE ENLIVENED HARLEM in a big way in the 1920s and ’30s, it has not been recognized as one of the art forms that launched the legendary Harlem Renaissance. Yet it was essential to the lives and imaginations of the period. People danced in theaters and basements, in ballrooms and night clubs, at rent parties and community centers. Dance shines through the poetry of Langston Hughes and Claude McKay, the novels of Jessie Fauset and Nella Larsen, and artworks by Aaron Douglas and Augusta Savage. A fledgling concert dance scene included Zora Neale Hurston’s stagings of authentic folk forms. Not only did dance flourish throughout the neighborhood, it helped make Harlem a magnet for people of all races and classes.

The Harlem Renaissance was sparked by W. E. B. Du Bois, who was determined to show that Black artistic talent, if given exposure, would blossom so visibly that it would win respect for Black people and help combat systemic racism. Central to this effort was Alain Locke’s anthology The New Negro (1925), which gathered work by a wide array of contributors, including Fauset, Hughes, Hurston, and McKay, as well as writer/activist James Weldon Johnson and poet Jean Toomer. With this profusion of writings, Locke intended to “register the transformation of the inner and outer life of the Negro in America.”[1] In subsequent editions, Arnold Rampersad called the movement “something approaching a cultural revolution.”[2]

However, the Harlem Renaissance was mostly a literary movement. Poetry, fiction, and playwriting were valued, along with visual arts and certain kinds of music—but not dance. From the point of view of Du Bois and Locke, dance endangered the project of elevating Black people in the eyes of the rest of the world. Dance was associated with minstrel shows—a horribly demeaning, century-long American tradition that represented exactly what they wanted to rise above.

In this essay, I consider the sites and situations where dance flourished, infusing this historic period with a vibrancy that did not always register as Art.

MUSICALS

With African Americans effectively banned from Broadway in the 1910s, they developed their own musicals, performing off Broadway for Black as well as white audiences.[3] In 1921, Shuffle Along, created by lyricist Noble Sissle and composer Eubie Blake, burst on the scene, breaking box-office records for months. Writing in Black Manhattan, James Weldon Johnson called it “epoch-making;” he pronounced the dancing in the show the “most exhilarating” in the city.[4] This is the show that brought fame to dancer/singer Florence Mills, introduced an unruly young chorus girl named Josephine Baker, and made Hughes dream of coming to Harlem.[5] Both Blacks and whites flocked to see Shuffle Along at the Cort Theatre on Broadway, creating such a traffic jam that 63rd Street had to be officially declared a one-way street. The dancing included buck and wing (an early version of tap), soft shoe, and slow-motion acrobatics, as well as the prancing and kicking typical of the Cakewalk. In her biography of Baker, Phyllis Rose quotes prominent critic Alan Dale on the powerful impact of the performers:

Every sinew in their bodies danced; every tendon in their frames responded to their extreme energy. They reveled in their work; they simply pulsed with it, and there was no let-up at all. And gradually, any tired feeling that you might have been nursing vanished in the sun of their good humor.[6]

This enthusiastic response reflects the growing craze in the twentieth century for Black music and dance. In addition to satisfying white people’s cultural curiosity, it had an emotional effect: It could improve the mood of white folks whose lives had become increasingly distanced from their physical selves with the onset of the machine age.

In Harlem Renaissance, historian Nathan Irvin Huggins credits Shuffle Along with ushering in the jazz age.[7] Scholar and dance historian Jacqui Malone points out the string of dance-rich Black musicals that followed, including Runnin’ Wild (1923), in which choreographer Elida Webb unleashed the Charleston mania; Dinah (1924), which introduced the Black Bottom; Dixie to Broadway (1924), first of several hit musicals produced by the white impresario Lew Leslie; and The Chocolate Dandies (1924), which featured Baker in a central role.[8]

In 2016, almost a hundred years after it first opened, Shuffle Along enjoyed a Broadway revival with the tagline “or, the Making of the Musical Sensation of 1921 and All That Followed.” Directed by George C. Wolfe and choreographed by Savion Glover, it featured a star-studded cast including Audra McDonald, Brian Stokes Mitchell, and Billy Porter. Although no longer a cultural high-water mark, this lively production did garner ten Tony nominations.

Even though the original Shuffle Along was such a hit—and some credit it with sparking the Harlem Renaissance—when Locke teamed up with editor Charles Johnson to create the precursor to The New Negro, they shared a vision that did not embrace Shuffle Along and its ilk. As scholar David Levering Lewis wrote:

Both wanted the same art for the same purposes—highly polished stuff, preferably about polished people, but certainly untainted by racial stereotypes or embarrassing vulgarity. Too much blackness, too much streetgeist and folklore — nitty-gritty music, prose, and verse — were not welcome…[9]

Locke and Charles Johnson considered the sexuality of the dancing in these shows to be crass and uncivilized. As they saw it, dance was not noble like the sorrow songs so poignantly described by Du Bois in the final chapter of The Souls of Black Folk (1903). The Fisk Jubilee Singers, with their repertory of Negro Spirituals—or “sorrow songs”—had toured the United States and Europe to great acclaim since 1871. Their widespread popularity fueled Du Bois’ idea that showcasing the talent of Black artists could garner broad respect for African Americans. In discussing these songs, Locke bemoans the reluctance to elevate them—or any folk art—to the level of high art, saying, “It still requires vision and courage to proclaim their ultimate value and possibilities.”[10] While he and other scholars recognized the artistic significance of the sorrow songs, they did not have the “vision and courage” to recognize dance as an art form.

By contrast, several of the younger Renaissance writers embraced dance as vital to life in Harlem. McKay, whose raunchy depiction of the neighborhood in his first novel, Home to Harlem (1928), antagonized Du Bois and Locke, loved Shuffle Along. He wrote that Blacks “have traditionally been represented on the stage as a clowning race. But I felt that if Negroes can lift clowning to artistry, they can thumb their noses at superior people who rate them as a clowning race.”[11] Substitute “dancing” for “clowning” and the message is the same: McKay believed that lifting vaudevillian song and dance to the level of “artistry” imbued those disparaged forms with dignity.

THE SAVOY

Shortly after it opened in 1926, the Savoy Ballroom became the first dance hall in Harlem to be racially integrated. In the late 1920s and ’30s, people of all races and classes frequented the Savoy—along with the Renaissance and the Alhambra ballrooms —to dance the Shag, the Shimmy, the Grizzly Bear, the Big Apple, the Black Bottom, the Charleston, and other new dances brewing in Harlem. The Savoy was the place that put the Lindy Hop on the map when its Saturday night dance competitions escalated to ever greater inventiveness and rambunctiousness. Whitey’s Lindy Hoppers, the professional group that emerged from these competitions, kept upping their game with mind-boggling dance moves. You may have seen the Lindy Hop clip from the Hollywood film Helzapoppin’ (1941) where six charged up dancer/acrobats go all out to the beat, with dancers shooting up into the air, grinding down into the floor, or hurling themselves at their partners.[12]

Hughes wrote in a letter that he was moved to tears by the interracial intermingling at the Savoy, and he realized how much Blacks had influenced mainstream American culture:

That was one of the things that got me to feeling like crying thinking how a simple thing like music-and not high-brow music, but popular music—the people’s music—could bring folks together, like at the Savoy Ballroom in Harlem where everybody dances with everybody else, white, West Indian, Filipino, Mexican, Negro, and nobody’s the worse for it. Then I got to thinking how this music was Negro music, and how Negro music had influenced all American popular music to such a great extent that it is now pretty hard to draw any color line at all in popular music. From George Gershwin up or down, white American composers have been influenced by, have improvised on and borrowed from the Negro composers and the folk songs of the Negro people, until our American popular music is flavored through and through with the sad-happy honey of the Negro soul.[13]

THE COTTON CLUB

In contrast to the diversity of the Savoy, Harlem nightclubs like the Cotton Club, Small’s Paradise, Connie’s Inn, and the Plantation, were places where Black entertainers—including choruses of light-skinned young women—performed for white audiences.

Music and dance came together in the persona of Cab Calloway, the legendary jazz singer and bandleader who presided over Cotton Club shows in the 1930s. With his outsized personality and charisma, he captivated audiences as he led his band. A quick survey of YouTube clips shows Calloway struttin’, truckin’, jivin’ and twisting in his long white tails as he conducted his swing band. He swiveled his hips seductively, trembled like renowned Harlem nightclub eccentric dancer Earl “Snake Hips” Tucker, and did an early version of the moonwalk—all within eight beats. The ultimate showman, he led band members not just with an oversized baton but with his hyperactive body—which you can see in this YouTube clip him in his signature song “Minnie the Moocher.” One of the musicians who was scheduled to follow him described the effect:

When Calloway came on for the second set he made a remarkably spectacular entry, leaping over chairs, turning somersaults, and indulging in all manner of non-musical showmanship, all the while singing… in his most eccentric manner. This so won over the audience that we didn’t dare go on again.[14]

Alyn Shipton, Calloway’s biographer, writes that in the 1934 film Cab Calloway’s Hi-De-Ho, he goes from “frenetic movement to slow drag walking… his movements drew on the entire vernacular of African American dance, with allusions to nineteenth-century survivals like buck and wing alongside comparatively recent fads like the black bottom.”[15]

Operating from 1923 to 1935, the Cotton Club catered to whites who could afford to buy alcohol during Prohibition. It was run by a white gangster who often used racial caricatures to promote his shows. Calloway described the decor as “a replica of a Southern mansion, with large white columns and a backdrop painted with weeping willows and slave quarters.”[16]

While Calloway was able to put up with this ugly racism—after all, it gave him the space to develop as a performer—Hughes deplored it. “I was never there,” he wrote in The Big Sea (1940), “because the Cotton Club was a Jim Crow club for gangsters and monied whites. They were not cordial to Negro patronage, unless you were a celebrity like Bojangles.”[17]

EARLY CONCERT DANCE

As white performers experimented with modern dance, a fledgling concert dance scene began to emerge in and around Harlem in the 1930s through the work of Hemsley Winfield and Edna Guy. A young actor and community theater producer, Winfield brought together a group of largely untrained dancers to form the Bronze Ballet Plastique. Influenced by Locke’s The New Negro, he changed the name of his dance troupe after its first performance to the New Negro Art Theater Dance Group. In 1931 his company of eighteen dancers performed what was billed as the “First Negro Dance Recital in America” to packed houses at Theater in the Clouds, a tiny midtown upstairs venue. Winfield produced dances with titles like Ritual, Bronze Study, Black Foundation, and Life and Death. Guy, a young dancer who had been held back by racial prejudice, performed two solos she learned from her white teacher and idol, modern dance pioneer Ruth St. Denis: A Figure from Angkor Wat and Temple Offering.[18]

Bronze Ballet Plastique in Life and Death, with Hemsley Winfield at Center, ph Martinus Anderson, via Nelson D. Neal

In 1931 Winfield and Guy also performed in Fast and Furious, a revue partly written by Hurston in which Winfield appeared in a comical “pansies” skit (at the time, pansy was a term for a gay, queer, or gender-non-conforming man). Winfield produced a version of Oscar Wilde’s Salome and even performed the role of Salome himself—thus inspiring a series of erotic drawings by Bruce Nugent. Three months before his tragic death at age 26, he and his group danced in an operatic production of Eugene O’Neill’s The Emperor Jones, becoming the first African Americans to perform at the Metropolitan Opera.[19]

After Winfield died, Edna Guy performed in her own concert in a studio at Carnegie Hall. More important, she co-organized (with Allison Burroughs) the Negro Dance Evening at the 92nd Street Y in 1937. One of the artists she invited was Katherine Dunham, and this marked Dunham’s NYC debut. (To learn more about the Y’s early welcome of Black dancers, I recommend Naomi Jackson’s book, Converging Movements: Modern Dance and Jewish Culture at the 92nd Street Y.)

During this same period, some white left-wing dance artists were reaching out to the Black community. Edith Segal’s duet Black and White Workers Solidarity Dance was first performed, by herself and Black dancer Allison Burroughs, at the Harlem Revels at Rockland Palace in 1930. (see Stepping Left: Dance and Politics in NYC 1928–1942, by Ellen Graff, p. 37.) It later became known as a duet for two men, in which a Black man and a white man took turns swinging a hammer. It was performed at many rallies and meetings but later was regarded as merely an agit-prop piece. In any case, it was part of a larger movement to try to integrate the Black and leftist dabce communities.

The Black press basically ignored concert dance until the arrival of Kykunkor (The Witch Woman), a “native African opera” choreographed by Asadata Dafora, at the Little Theater in 1934. An immigrant from Sierra Leone, Dafora combined European and African influences in a production staged at several venues including the Harlem YMCA. Writing in Opportunity, the journal of the National Urban League, Locke applauded its “primitive cleanliness and vitality instead of the usual degenerate exoticism and fake primitivism to which we have been accustomed.”[20] White critic John Martin called it one of the most exciting dance performances of the season.”[21] Dafora’s career took off, and, in 1937 he choreographed Bassa Moona: The Land I Love, a dance opera with forty actors and thirty dancers, at Harlem’s 1,500-seat Lafayette Theatre. (For more on Dafora, see Perpener’s essay in Jacob’s Pillow’s Dance Interactive here.)

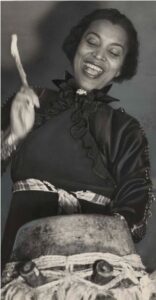

Hurston’s productions of folk dances from the African diaspora offered another form of concert dance. In addition to being a major literary light, she was an anthropologist who researched dance forms of the American South and the Bahamas. Hurston organized at least twenty-five performances in New York, Chicago, and other cities featuring a group of Bahamian dancers, whose concerts typically culminated in the kinetically charged “Bahamian Fire Dance.” Originally the last scene in her play “The Great Day” (1932), this ritual consisted of three sections: a “Jumping Dance,” “Ring Play” (which involved partnering), and the “Crow Dance.”[22] This finale proved to be such a tour de force that it resurfaced in multiple incarnations in productions by both Hurston and others. (A rudimentary clip of Hurston’s “Crow Dance,” with her voice explaining and singing, can be seen here.)

DRAG BALLS

In the late nineteenth century, the Hamilton Lodge—built as an Odd Fellows hub in 1869—hosted events known as “masquerade and civic balls.” By the 1920s, these events had gained greater visibility—and flamboyance—eventually morphing into what was dubbed the “fairies’ ball.”[23] Unsurprisingly, the architects of the Renaissance looked down on queer culture as much as on dance, but younger writers and artists felt free to form their own opinions.

At a time when the Cotton Club and Connie’s Inn excluded Black patrons, the Hamilton balls attracted a racially diverse crowd.[24] Hughes recalled that movie stars like Beatrice Lillie and Tallulah Bankhead would watch from the balcony above.[25] Scholar George Chauncey estimates the number of drag queens at these events to be in the hundreds and spectators to be in the thousands.[26] In fact, audiences for the balls became so massive that sometimes they were held at the Astor Hotel or even Madison Square Garden.[27]

Other Harlem venues that held similar parties included the Rockland Palace, Lulu Belle (named after the provocative 1926 musical, which included Hemsley Winfield in its cast), and Cyril’s Café. This was all part of the “pansy craze” sweeping New York (as well as Los Angeles, London, Paris, and Berlin).[28] A high point of these evenings was the “parade of pansies” that preceded the official costume competition. A 1932 newspaper article in The New York Amsterdam News with the headline “Hamilton Lodge Ball Draws 7,000” explains it this way:

The “beauty” pageant started at 1:45 am. Bowing, throwing kisses, snake-hipping or Lindy-hopping as the mood struck them, nearly 100 of the more expensively costumed impersonators strode across an elevated platform and courted the favor of the crowd and judges. From this group a score of semi-finalists were chosen.[29]

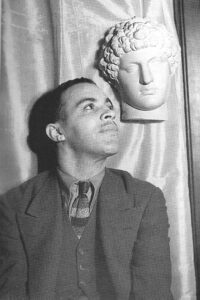

Nugent’s posthumous collection Gay Rebel of the Harlem Renaissance celebrates just how fabulous these balls were. He had danced with both Winfield and, later, Wilson Williams’ short-lived Negro Ballet Company, which performed at the Humphrey-Weidman studio in 1941 and 1942.[30] Nugent describes one masked ball as follows:

“We arrived late, and the dance floor was a single chaotic mass of color. Abbreviated ballet skirts of pink, blue, silver and white dancing with Arab sheiks in fantastic colors. Turks with bright ballooned trousers, curled pointed boots and turbans with sweeps of brilliant feathers and sparkling glass gems… pirates in frayed trousers, bloody shirts, headbands, earrings and tattoos …Apache Indian, Spanish, Dutch and Japanese girls.”[31]

In the foreword to Gay Rebel, Henry Louis Gates Jr. emphasizes that the drag balls did not belong to a nefarious gay underworld but were so much a part of Harlem’s public life that they were often covered in the Amsterdam News.[32] Supporting Gates’ view is a recent article by Tsione Wolde-Michael, who traces the current voguing scene back to the Harlem Renaissance and makes the point that the gay movement in Harlem played out very publicly, seeding the fluid gender structures we are seeing today:

Many of the movement’s leaders were openly gay or identified as having nuanced sexualities including Angelina Weld Grimké, Claude McKay, Langston Hughes, Wallace Thurman, Alice Dunbar-Nelson, Alain Locke, and Richard Bruce Nugent, among others. The movement offered a new language that challenged social structures and demonstrated the ways that race, gender, sex, and sexuality distinctions were actually intersecting, fluid, and constantly evolving.[33]

Although the line from the parade of pansies to today’s voguing ballroom scene may not be perfectly straight, a discernible thread clearly connects the two.

DANCE IN RENAISSANCE LITERATURE

In poetry and novels of the period, dance held a prominent place but meant something different for older versus younger writers. For the former, dance represented either an obligation or a humiliation. For the latter, it allowed for exuberance and self-expression.

Novelists Jessie Fauset and Nella Larsen were both aligned with Locke’s sense that dance was not a bona fide form of art. For Joanna, the protagonist in Fauset’s novel There Is Confusion (1924), dance is a profession that becomes an obstacle to love. Like many aspiring Black dancers, she endures the humiliation of needing to arrange for separate lessons for non-white students, but by the end of the novel she loses interest in dance. In a disappointingly unliberated move, Joanna opts to stop going to dance classes in order to devote herself exclusively to marriage. Given that Fauset was a colleague and disciple of Du Bois, it is not surprising that dance is seen as an obstacle in her world.

In Larsen’s Quicksand (1928), dance provides a turning point—a revelation really—for mixed-race protagonist Helga Crane. As a guest in Denmark, she joins a white audience at a vaudeville show. In the final act, when two Black performers “danced and cavorted,” and the audience “clapped and howled and shouted for more,” Helga is horrified by both the grotesque performance and the audience’s response.[34] However, she is drawn to the show repeatedly, attempting to understand its meaning. Is this why her Danish hosts dress her up in bright-colored outfits? Do they see her as nothing more than a curiosity, an animal in the zoo? Ultimately, she decides to return to Harlem, where she can be herself—or at least half of herself—without being stared at.

For younger writers likes Hughes and McKay, dance held a Dionysian allure. Hughes used dance to express a special vitality or a connection to nature. In his poem “Danse Africaine,” a veiled girl “Whirls softly, slowly / Like a wisp of smoke around the fire” while the beating of the tom-toms “stir your blood.” His poem “Dancers” expresses a similar sentiment:

Stealing from the night / A few / Desperate hours / Of pleasure.

Stealing from death / A few / Desperate days / Of life.[35]

Similarly, for McKay, dance represents total abandon. In his poem “Negro Dancers,” people dance in order to lose themselves—to let go of the burdens of everyday life: “Dancing, their world of shadow to forget.” And later, “Dead to the earth and her unkindly ways of toil and strife / For them the dance is the true joy of life.” The dancing has “Not one false step, no note that rings not true.”[36] It is also “true” because it is done freely, not to impress anyone, and it brings the subjects closer to their true selves. When McKay writes, “They dance with poetry in their eyes,” he seems to suggest that, in touching the soul, dance is elevated to art—as were the sorrow songs.

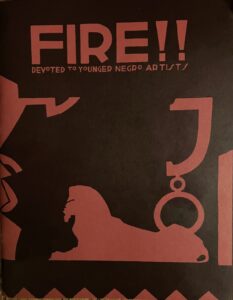

Hughes, McKay, and others had their day in the sun when a group of them got together to start a new literary journal called Fire!!, described as “A Quarterly Devoted to the Younger Negro Artists.” According to Nugent, the idea for the journal arose from long walks and talks he had with Hughes.[37] They wanted to create a publication that was less reverent, less aired at impressing white folks. The first (and what turned out to be the only edition of Fire!! came out in November 1926, only a few months after Locke published The New Negro. It included drawings, essays, short stories, commentary, and poems contributed by not only Nugent and Hughes, but also Hurston, Arna Bontemps, Countee Cullen, Aaron Davis, and Wallace Thurman, among others.

One of Hurston’s two contributions was “Color Struck,” a play in which the climactic event is a Cakewalk competition. She describes the revelers strutting, parading, prancing, and holding up their skirts to show the lace underneath. This was not the type of cultural event the Black intelligentsia considered artistic. As dance scholar John O. Perpener III has pointed out:

Harlem Renaissance artists and intellectuals engaged in ongoing debates about the appropriate framing of black cultural expressions. Bourgeois members of the intelligentsia supported the high-art versions of black folk music, while Hurston opted for presenting the “real” thing.[38]

“Color Struck” takes place in Florida, where the winners apparently really take the cake—a humongous one made with three dozen eggs. But more to the point, Hurston describes the competition in a way that makes it clear how this dance mocked plantation owners. It begins with a grand promenade in which couples are “prancing” in place, warming up. Two men carrying the huge cake lead the procession, and before the couples begin to dance, each man doffs his top hat to sweep into an elaborate bow, while his partner lowers into a deep curtsy. The couples begin to strut together, often with a comically stiff formality that alludes to the highly mannered dances of white slaveholders. “Fervor of spectators grows until all are taking part in some way—either hand-clapping or singing the words. At curtain they have reached frenzy.”[39] Hurston shows that the Cakewalk was both a defiant performance and an entertaining community event.

DANCE IN THE VISUAL ARTS

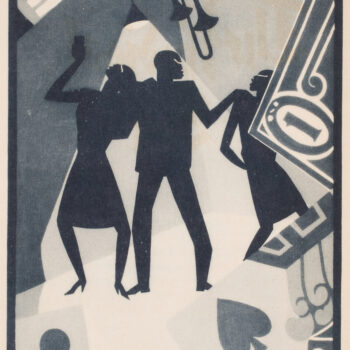

Aaron Douglas, perhaps the most celebrated Black visual artist of the time, developed a style that merged modernism with African traditions—using bold figures, angled limbs, and silhouettes reminiscent of ancient Egypt. His stark graphic style graced the pages of The New Negro and many covers of Crisis, the magazine of the NAACP edited by Du Bois and Fauset that helped establish Harlem as the hub of Black resistance.[40]

Like Locke and Du Bois, Douglas believed that art should elevate the Black image in order to resist the oppressiveness of slavery and Jim Crow. He was inspired by Du Bois but disagreed on one point: He felt that dance did help lift and define Black culture. In a 1936 essay, Douglas wrote:

The dance offered a field for the unrestricted expression of the Negroes’ creative passion. Here were no expensive instruments to be purchased, no weird symbols to be mastered, no unfamiliar tools and stubborn material to be overcome, only swift feet, strong legs, a lust for life and a soaring imagination. With this limited equipment the Negro has kept folk dancing alive in America when it has died almost everywhere else in the world. He has not only kept the dance alive, but in a spontaneous, revolutionary, creative state.[41]

Perhaps Douglas’ grandest ode to dance was a large mural called Evolution of Negro Dance created for the Harlem YMCA in 1935. Still visible on the wall of what is now a multipurpose room, the silhouetted figures tell a story that can be read from left to right: People crouching close to the ground with a ritual feeling (left) yield to fancy folks in top hats and poofy dresses (center), and then to a man in bowler hat playing a banjo (right). Though the mural is sorely in need of restoration, it still reveals the artist’s stylized shapes and masterful composition.

Many other paintings by Douglas depict dancing or jazz musicians. In The Congo several women—possibly nude, seen through a haze—respond to an unseen whirlwind. In Dance Magic a single woman dances in a nightclub, wearing provocative tassels. His illustrations for God’s Trombones (1927), a series of seven sermons in verse form by James Weldon Johnson, present each biblical scene— from “Creation” to “Judgment Day”—as a dance. According to Douglas’ biographer, jazz music “provided the backdrop for this series.”[42]

In some Douglas paintings such as Sahdji and I Couldn’t Hear Nobody Pray, a solo figure appears in counterpoint to a group. The silhouetted figures are so clear and the groupings are so well composed that these paintings evoke skillful choreography frozen in time.

INNOVATION AND IMPROVISATION

In both social and concert dancing, innovation was highly valued. Dance historian Jacqui Malone makes a point of the individuality expressed at both the Savoy and the Apollo.[43] Each dancer strove to create an individual style in order to stand out and be noticed.

In the early twentieth century, Bill “Bojangles” Robinson had become a top name in vaudeville through constant experimentation. He developed speed, precision, and crystal clarity of sound, all while keeping a natural, elegant upper body.[44] Critic Robert Benchley called his quality “indescribably liquid, like a brook flowing over pebbles.”[45] Robinson brought tap dancing onto the balls of the feet, changing it from flat-footed buck dancing by infusing it with a sense of uplift. His famous stair dance was a wonder of elegance and ingenuity. When he was lured to Hollywood in the 1930s, he teamed up with the white child star Shirley Temple to make entertainment history as the first interracial duo to dance and sing together in four films.

Harlem was a magnet for other tappers, too. Between 1927 and 1934, Peg Leg Bates came from South Carolina, Charles “Honi” Coles and the Nicholas Brothers from Philadelphia, Baby Laurence from Baltimore, and Eddie Brown from Omaha, among others.[46] Many of them gathered at the Hoofers Club, a basement studio near the Lafayette Theatre. According to dance historian Constance Valis Hill, their jam sessions sometimes lasted all night as they challenged each other with variations of over-the-top, five-step wings, and backward trenches.[47] Apparently, their guiding rule was “Thou shalt not copy each other’s step—exactly.” [48] In fact, “stealin’ steps” was a way for each dancer to develop their own style and extend their range. The dancers allowed into the Hoofers Club were mostly Black men, although the charismatic young dancer Jeni LeGon was possibly the only woman to show up and be invited back.[49] In addition to Robinson, Coles, and Laurence, the regulars included John W. Bubbles, Leonard Reed, and Eddie Rector.

The hoofers were tough on each other. If they did not think a dancer was laying down the iron, they would let him know. Bubbles was an experimenter and improviser who first came to the Hoofers Club as a teenager with a vaudeville act. When he showed his steps, he was laughed at—someone yelled, “You’re hurting the floor!”[50] Months later, after practicing in California, Bubbles returned, ready with a sure-fire original sequence. “Man, I was really fortified. Like a fellow with a double-barreled shotgun—who’s gonna stop me?”[51] According to Bubbles’ biographer Brian Harker, his new style was “fast and complex, audacious and unpredictable.” Instead of dancing on the balls of his feet like Robinson, he brought his weight back down to the heels and cut the tempo so he could pack his moves with syncopation. Bubbles may have been influenced by Lancaster clog dancers on the vaudeville circuit. “I took the white boys’ steps and the colored boys’ steps and mixed ’em all together so you couldn’t tell ’em, white from colored.”[52] Harker contends that his dancing “resembled the freewheeling solos of the great jazz artists of his time.”[53] In a wonderful clip from the Buck and Bubbles Varsity Show (1937)—where he performs with a partner—the duo’s comedic routine, snazzy steps, and impeccable timing are clear.[54] (My review of Harker’s biography is third one down in this link.)

The complex style Bubbles created was eventually called rhythm tap. Harker claims that jazz drumming was “rudimentary compared with rhythm tap.” Coles recalled that when jamming with the tap dancers, the drummers were able to deepen their own art.[55] Rhythm tap really caught on among young dancers. “Everybody during my maturing years wanted to be like Bubbles,” said Coles.[56]

Some of the dancers developed such a unique style that they became known as “eccentric dancers.” Rector developed his own way of combining new rhythms with free-flowing traveling steps and also performed atop three huge kettle drums.[57] A dancer named Johnnie Hudgins specialized in Chaplinesque hand and arm gestures.[58] Possibly the most far-out eccentric dancer was Earl “Snake Hips” Tucker, who would throw his hips way off to the side, undulate his spine outrageously, and then send a feverish shudder throughout his body.[59]

Improvisation was key to both social and stage dancing. At Saturday-night rent parties, as Hughes wrote, “the dancing and singing and impromptu entertaining went on until dawn came in at the windows.”[60] Often a well-known pianist like Fats Waller was hired, and revelers would be doing the Slow Drag. This was a couples dance with the loosest of structures, with partners first dancing together closely and slowly before separating and improvising their own steps. Renowned dancer and Lindy Hop master Frankie Manning recalls numerous variations of the Charleston that people came up with: “turnover Charleston, hand-to-hand Charleston, flying Charleston, long-legged Charleston, squat Charleston.”[61]

In describing rehearsals for shows on the TOBA circuit (the Black vaudeville network officially known as the Theater Owners Booking Association), Malone points out that directors and dancers “helped cultivate an atmosphere that encouraged improvisation on a wide scale.”[62] As end-girl in Shuffle Along, for instance, Josephine Baker kept the basic steps but added “crazy things.”[63] Once she was cast in the next Sissle and Blake production, The Chocolate Dandies, she started to develop her solos through improvisation. “She was a jazz artist,” wrote Rose in her biography, “and her inspired solos, while they took place in a context that had its own discipline, were great because of her gift for spontaneous invention.”[64] Needless to say, this combination of discipline and spontaneity took her on a ride all the way to Paris.

Like Baker, the Bahamian dancers organized by Hurston also improvised within a set structure. They felt so possessive of their own inventions that, as Hurston observed, sometimes they fought with each other about who “owned” the steps.[65]

As with literature and music, dance raised issues about class differences. As Danielle Robinson points out, the Slow Drag could be sexually suggestive, and conveyed a sense of backwoods milieu, of Black culture before it migrated north. Considered authentically Black by a younger generation, it was dismissed as too “lowdown” by Harlem elites. When the Slow Drag surfaced at the Apollo in Wallace Thurman’s play Harlem, the dance-along with Black slang and other elements some considered crude— created controversy.[66]

BLACK DANCE AS A SOURCE FOR WHITE DANCE

In the late 1920s, “white show business needed new dances,” according to Marshall and Jean Stearns, “and was beginning to realize that the Negro was an inexhaustible source.”[67] In 1914, the impresario Florenz Ziegfield bought a dance routine from the Black hit Darktown Follies 1914) for the Ziegfield Follies.[68] A few years later, famous white entertainers like Lucille Ball, Eleanor Powell, Paul Draper, Adele and Fred Astaire, and Mae West frequented the Billy Pierce Dance Studio in midtown to take lessons from Buddy Bradley.[69] A largely self-taught tapper, Bradley would teach all day, sometimes working with two students at a time. Black dancers like him got paid to choreograph for white performers but did not get credit for doing so.[70] As he explained:

Soloists always needed routines, so the black dancer, if he could put something together, could make some money. Not get recognition, mind you; we knew that the public would always think the stars just grew up talented and wonderful.[71]

While this imbalance was steeped in the racist attitudes of the time, Robinson points out that the desire of whites to learn Black dances enabled people like Bradley to establish teaching as a viable profession at a time when few Blacks could get jobs that paid as well. As their economic status rose, these dancers were able to join the middle class.[72]

Bradley also assisted Hollywood mastermind Busby Berkeley on several films, and worked on projects with ballet greats Anton Dolin, Frederick Ashton, and Léonide Massine.[73] Other choreographers—from George Balanchine to Jack Cole, Bob Fosse, and Jerome Robbins—also trekked up to Harlem to check out the dance scene there.[74]

When white performers are influenced by Black dance, this type of borrowing is now widely considered to be cultural appropriation. Smith, however, simply calls it “pollination.”[75] The fact that the Black vernacular found its way into white culture was also seen as positive by James Weldon Johnson. In her foreword to the 2021 edition of his Black Manhattan, novelist Zadie Smith writes,

Whereas today “appropriation” is often viewed as cultural theft, for Johnson’s generation, to be worthy of appropriation signaled you had something worth appropriating, and therefore was a matter of pride.[76]

I cite these two viewpoints not because I agree or disagree, but to present another angle on today’s debates about the issue.

THE MARGINALIZATION OF DANCE

Although dance played a central role in the Harlem Renaissance, it was not recognized as important by scholars of the period. Neither Huggins nor Lewis mentions dance—other than incidentally—in their scholarly assessments of the Renaissance.

Among literary heavyweights of the time, only James Weldon Johnson placed dance on an equal footing with other art forms. In his classic memoir about racis, The Autobiography of an Ex-Colored Man (1912), he exulted in the beauty of the Cakewalk. He had seen the international star Aida Overton Walker give this boisterous dance a measure of grace, earning the well-deserved nickname “Queen of the Cakewalk.” Johnson deemed this dance to be one of the great accomplishments of Black culture, along with sorrow songs and ragtime music, calling them “lower forms of art… that will some day be applied to the higher forms.”[77]

A few recent dance scholars, however, have argued that dance was already a “higher form of art.” In his book Grown Deep: Essays on the Harlem Renaissance, Richard Long wrote:

Black dance in its exalting and spirit-enhancing role in African life and in its utilitarian but also redemptive role in the folk life of the Diaspora is one of the great creations of the human spirit.[78]

Amen. But it was not until Perpener’s landmark book African-American Concert Dance: The Harlem Renaissance and Beyond (2001) that a scholar treated dance from this period seriously. After acknowledging that “dance was not held in high esteem as a theatrical art by the intelligentsia,” Perpener goes on to say:

In the world of cabarets, nightclubs and house parties, however, dance was the generator that propelled the frenetic escapism and optimism of the time. It physicalized the pervading spirit of abandon of the 1920s.[79]

CARRYING IT FORWARD

Katherine Dunham, who took the dance world by storm in the 1940s and ’50s, had actually been involved in the wider New Negro Movement as it spread to cities beyond New York. She had met Hughes and Bontemps in Chicago, where they were part of the milieu of the Cube Theatre. Her brother Albert, a protégé of Locke, had established this venue as part of the “little theater” movement that later became known as community theater.[80] Unlike Du Bois’ Krigwa Players in New York, the Cube Theatre was racially integrated [81] and Dunham referred to it as “a people’s liberation group.”[82]

Joanna Dee Das, Dunham’s most recent biographer, points out that the Black Renaissance in Chicago hit its stride a decade after Harlem’s. She writes that after her anthropological field work in the Caribbean, Dunham’s performances “would enrich the transnational dimensions of the New Negro Movement in Chicago and alert fellow intellectuals to pay attention to the dancing body as part of their investigations into the black experience.”[83] When she moved to New York in 1939, she lived in Lower Manhattan but often went uptown to visit. “In Harlem I learned the fine points of jitterbugging, which always reminded me of the Jamaican mento or shay-shay,” she recalled. “We danced Cuban rumbas and boleros at the Campo Amor on Lenox Avenue and Lindy Hop at Small’s Paradise.”[84]

Archie Savage, who had danced with Hemsley Winfield in the 1920s, became a leading dancer with the Dunham company the following decade, forging a direct link from the early concert scene in Harlem to the world tours of what became the Dunham juggernaut by the 1940s.

In 1943 dancer/choreographer and African dance advocate Pearl Primus named one of her dances after “The Negro Speaks of Rivers,” the Hughes poem that signaled the dawn of a new consciousness among young Black poets.[85] In this way she honored one of the great figures of the Harlem Renaissance.

And then there’s Bruce Nugent, the dancer/writer who had performed with Winfield and frequented Harlem’s drag balls. He not only created a bridge between the gay scene of the Harlem Renaissance and post-Stonewall culture, he also helped rebuild Harlem’s arts institutions in the 1960s. He was a co-founder of the Harlem Cultural Council (HCC), which funded the DanceMobile and Jazz-Mobile—flatbed trucks that brought dance and music to the inner city.[86] (Interestingly, one of the mainstays of the DanceMobile was Eleo Pomare, whose own style of non-binary strutting anticipated voguing at drag balls.) The HCC procured political support for a new building for the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture (a branch of NY Public Library), which houses many dance archives. Nugent also played a key role in challenging the Metropolitan Museum of Art to redress its customary exclusion of Blacks, resulting in the 1969 exhibition Harlem on My Mind.

In addition, the Harlem Renaissance flowed into the modern dance of today through the friendship between Langston Hughes and Alvin Ailey. As documented in Jennifer Dunning’s excellent biography of Ailey, the two worked together on a number of projects involving the Blues. One of these was the play “Jericho-Jim Crow,” which opened in Greenwich Village in 1964 to positive reviews.[87] Twenty-three years earlier, Hughes had attempted to collaborate with Dunham, but nothing came of it. However, he worked with Anna Sokolow on Kurt Weill’s 1929 production of the operatic Street Scene, writing the lyrics while she did the choreography.[88]

In the realm of dance, Ailey’s transcendent ballet Revelations (1960) in a way fulfills Du Bois’ original vision for the Harlem Renaissance. Performed to some of the same spirituals that were sung by the Fisk Jubilee Singers—the very group that helped inspire his vision—it has been seen by 23 million people in 71 countries, according to the Kennedy Center website. This beloved ballet, which conveys joy overcoming struggle, arouses admiration and respect for Black people all over the world.

Obviously, the Harlem Renaissance did not accomplish Du Bois’ goal of diminishing racism in America. But it remains a vibrant period in history that laid the foundation for African American artists to blossom and thrive. In a less visible way than in literature—and with fewer famous names—dance infused Harlem with its infectious energy. It inspired artists in other disciplines to test their wings and discover their own versions of freedom. At the same time, dance was a catalyst for the growing awareness of the complexities of race and class. The Renaissance eventually led to the swing era, a period in which Black vernacular dance spread like wildfire and merged with white culture to become American culture.

§§§

Special thanks to Peter Kayafas, who helped shape this essay, to Mary Louise Patterson and Jim Siegel for their advice, to Angelina Hoffman for photo research, and to Thomas DeFrantz, who shepherded the first version of this essay, which was published in EmBODYing Liberation: The Black Body in American Dance, edited by Dorothea Fischer-Hornung and Alison D. Goeller for Forecaast, in 2001.

Special thanks to Peter Kayafas, who helped shape this essay, to Mary Louise Patterson and Jim Siegel for their advice, to Angelina Hoffman for photo research, and to Thomas DeFrantz, who shepherded the first version of this essay, which was published in EmBODYing Liberation: The Black Body in American Dance, edited by Dorothea Fischer-Hornung and Alison D. Goeller for Forecaast, in 2001.

NOTES

[1] Arnold Rampersad, “Introduction,” in Alain Locke, ed., The New Negro (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1997 [1925]), p. xxvi.

[2] Locke, The New Negro, p. ix.

[3] Lynne Fauley Emery, Black Dance: From 1619 to Today (Princeton, NJ: Princeton Book Co., 1988), p. 213.

[4] Ibid., p. 186.

[5] Langston Hughes, The Big Sea (New York: Hill, 1997 (1940), p. 62.

[6] Phyllis Rose, Jazz Cleopatra: Josephine Baker in Her Time (New York: Vintage Books, 1991), p. 55.

[7] Nathan Irvin Huggins, Harlem Renaissance (New York: Oxford University Press, 1971), p. 289.

[8] Jacqui Malone, Steppin’ on the Blues: The Visible Rhythms of African American Dance (Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press, 1996), pp. 75-78.

[9] David Levering Lewis, When Harlem Was in Vogue (New York: Random House, 1991 (1979]). p. 95.

[10] Locke, The New Negro, p. 199.

[11] Emery, Black Dance, p. 224.

[12] “Whiteys Lindy Hoppers…Helzapoppin” (video),

[13] Evelyn Louise Crawford and Mary Louise Patterson, eds., Letters from Langston: From the Harlem Renaissance to the Red Scare and Beyond (Oakland, CA: University of California Press, 2016), p. 238.

[14] Alyn Shipton, Hi-De-Ho: The Life of Cab Calloway (New York: Oxford University Press, 2010), pp. 39-40.

[15] Ibid., p. 60.

[16] Ibid., p. 37.

[17] Hughes, The Big Sea, pp. 224-25.

[18] Richard A. Long, The Black Tradition in American Dance (New York: Rizzoli, 1989), p. 25.

[19] For more on Winfield’s tragically short career, see my essay on him here.

[20] Susan Manning, Modern Dance, Negro Dance: Race in Motion (Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 2004), p. 54.

[21] John O. Perpener III, African American Concert Dance: The Harlem Renaissance and Beyond (Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press, 2001), P. 111

[22] Anthea Kraut, Choreographing the Folk: The Dance Stagings of Zora Neale Hurston (Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 2008), p. 72.

[23] James F. Wilson, Bulldaggers, Pansies, and Chocolate Babies: Performance, Race, and Sexuality in the Harlem Renaissance (Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press, 2010), p. 82.

[24] Ibid., p. 86.

[25] George Chauncey, Gay New York: Gender, Urban Culture, and the Making of the Gay Male World, 1890–1940 (New York: Basic Books, 2019 [1994]), p. 310.

[26] Ibid., p. 245.

[27] Ibid., p. 310.

[28] Ibid., p. 12.

[29] Quoted in Wilson, Bulldaggers, Pansies, and Chocolate Babies, p. 86. This description sounds much like the voguing ballroom scenes in the recent FX series Pose, which focused on New York City’s LGBTQ subculture in the 1980s.

[30] Thomas H. Wirth, ed., Gay Rebel of the Harlem Renaissance: Selections from the Work of Richard Bruce Nugent (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2002), p. 33.

[31] Ibid., p. 100.

[32] Ibid., pp. xi-xii.

[33] Tsione Wolde-Michael, “A Brief History of Voguing.” on Smithsonian website at https://nmaahc.si.edu/explore/stories/brief-history-voguing

[34] Nella Larsen, Quicksand and Passing (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1986 [1928, 1929]), pp. 82-83.

[35] Langston Hughes, The Collected Poems of Langston Hughes (New York: Random House, 1994), p. 334.

[36] Locke, The New Negro, p. 214.

[37] Oral history interview with Bruce Nugent conducted by Jean Blackwell Hutson, 1982. New York Public Library, Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture.

[38] John O. Perpener III, “The Dance Legacy of Zora Neale Hurston.” Dance Chronicle 33.1 (2010), p. 162.

[39] Zora Neale Hurston, “Color Struck: A Play in Four Scenes,” in FIRE!!: A Quarterly Devoted to the Younger Negro Artists (1926), p. 12.

[40] Amy Helene Kirschke, Aaron Douglas: Art, Race, and the Harlem Renaissance (Jackson, MS: University Press of Mississippi, 1995), p. 65.

[41] Matthew Baigell and Julia Williams, eds., Artists Against War and Fascism: Papers of the American Artists’ Congress (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1986 (1936), p. 79.

[42] Kirschke, Aaron Douglas, p. 41.

[43] Malone, Steppin’ on the Blues, p. 101.

[44] Megan Pugh, American Dancing: From the Cakewalk to the Moonwalk (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2015), pp. 29-83.

[45] Marshall Winslow Stearns and Jean Stearns, Jazz Dance: The Story of American Vernacular Dance (New York: Da Capo Press, 1994 (1968]), p. 156.

[46] Brian Harker, Sportin’ Life: John W. Bubbles, an American Classic (New York: Oxford University Press, 2022), p. 137-138.

[47] Constance Valis Hill, Tap Dancing America: A Cultural History (New York: Oxford University Press, 2010), p. 87.

[48] Rusty E. Frank, Tap! The Greatest Tap Dance Stars and Their Stories, 1900-1955 (New York: Da Capo Press, 1990), p. 42.

[49] Ibid., p. 126.

[50] Steven Watson, The Harlem Renaissance: Hub of African-American Culture, 1920-1930 (New York: Pantheon Books,1995), P. 112.

[51] Harker, Sportin’ Life, p. 71.

[52] Ibid., p. 73.

[53] Ibid., p. 74.

[54] “Buck and Bubbles Varsity Show-1937” (video), https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dCpKx64EivE.

[55] Harker, Sportin’ Life, p. 141.

[56] Ibid., p. 138.

[57] Marian Horosko, “Tap, Tapping, and Tappers.” Dance Magazine (October 1971), pp. 32-37.

[58] Stearns and Stearns, Jazz Dance, p. 146.

[59] Ibid., p. 237.

[60] Hughes, The Big Sea, p. 229.

[61] Frankie Manning and Cynthia R. Millman, Frankie Manning: Ambassador of Lindy Hop (Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press. 2001.

[62] Malone, Steppin’ on the Blues, p. 81.

[63] Stearns and Stearns, Jazz Dance, p. 134.

[64] Rose, Jazz Cleopatra, p. 60.

[65] Kraut, Choreographing the Folk, p. 65.

[66] Danielle Robinson, Modern Moves: Dancing Race during the Ragtime and Jazz Eras (New York: Oxford University Press, 2015), pp. 35-43.

[67] Stearns and Stearns, Jazz Dance, p. 163.

[68] Long, The Black Tradition, p. 85; Stearns and Stearns, Jazz Dance, p. 125; and Hill, Tap Dancing America, p. 45.

[69] Hill, Tap Dancing America, p. 85; and Horosko, “Tap, Tapping, and Tappers,” p. 35.

[70] Stearns and Stearns, Jazz Dance, p. 162.

[71] Horosko, “Tap, Tapping, and Tappers,” p. 35.

[72] Robinson, Modern Moves, pp. 129–148.

[73] Long, The Black Tradition, p. 38; and Pugh, America Dancing, p. 121.

[74] Watson, The Harlem Renaissance, p. 109.

[75] Norma Miller and Evette Jensen, Swingin’ at the Savoy: The Memoir of a Jazz Dancer (Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press, 1996), p. xix.

[76] James Weldon Johnson, Black Manhattan (New York: IG Publishing, 2021 [1930]), p. xiv.

[77] James Weldon Johnson, The Autobiography of an Ex-Colored Man (New York: Compass Circle, 2019 [1912]), p. 53.

[78] Richard A. Long, Grown Deep: Essays on the Harlem Renaissance (Winter Park, FL: Four-G Publishers, 1998), p. 93.

[79] Perpener, “African American Dance,” p. 17.

[80] VèVè A. Clark and Sara E. Johnson, eds., Kaiso! Writings by and about Katherine Dunham (Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press, 2005), p. 109.

[81] Joanna Dee Das, Katherine Dunham: Dance and the African Diaspora (New York: Oxford University Press, 2017), p. 19.

[82] Clark and Johnson, Kaiso!, p. 420.

[83] Das, Katherine Dunham, pp. 36-37.

[84] Katherine Dunham, “Early New York Collaborations,” Clark and Johnson, Kaiso!, p. 136.

[85] Long, The Black Tradition, p. 76.

[86] Wirth, Gay Rebel of the Harlem Renaissance, p. 37.

[87] Jennifer Dunning, Alvin Ailey: A Life in Dance (Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley, 1996), pp. 177-78.

[88] Larry Warren, Anna Sokolow: The Rebellious Spirit (Amsterdam: Harwood Academic Publishers, 1998), pp. 83-84.

Historical Essays Leave a comment