A few years ago, as editor at large for Dance Magazine, I was asked to produce short video previews of exciting dance happening in the NYC area. Along with video producer Kelsey Grills, I created 37 “What Wendy’s Watching” from September of 2017 to December of 2018. I had fun with this because I love all the dance houses where we filmed these, and I tried to give a bit of context with each preview. Actually not all were previews. Occasionally I commented on an event that already happened. I am posting the links here because they are hard to find on the Internet. The following are roughly in chronological order:

Dance Now at Joe’s Pub, including clips of works by Jane Comfort and Sara Pearson, Sept. 2017

20 Fall for Dance Companies in 2 Minutes, Sept. 2017

Chatting with the Stars at the Chita Rivera Awards, Al Hirschfeld Theatre, Sept. 2017

Eiko’s Haunting Vision Comes to the Metropolitan Museum, Nov. 2017

Nora Chipaumire Comes to Alliance Française, Sept. 2017

Anne Teresa de Keersmaeker Tackles Coltrane at NYLA, Sept. 2017

Twyla Brings Old and New to the Joyce, Oct. 2017

The 3 Best Moments of NYCB fall season, including Tiler Peck’s debut in Swan Lake

Can The Red Shoes Ever Be Contemporary? NY City Center, Nov. 2017

David Dorfman Portrays Tenderness and Hope at BAM’s Next Wave, NOv. 2017

Stepping into Black History with Step Afrika! New Victory Theater

Trisha Brown’s Rarely Performed Works at the Joyce, Dec. 2017

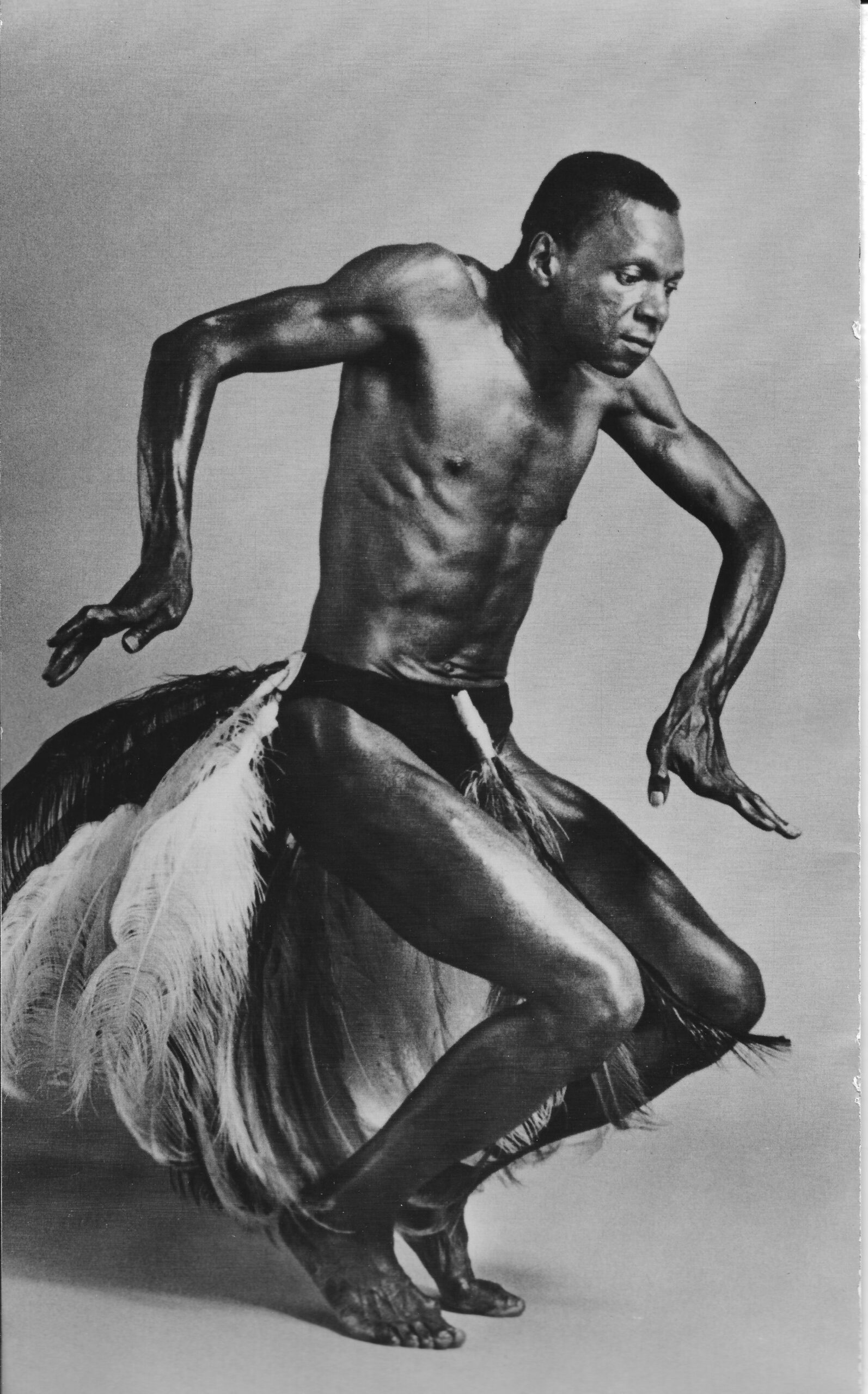

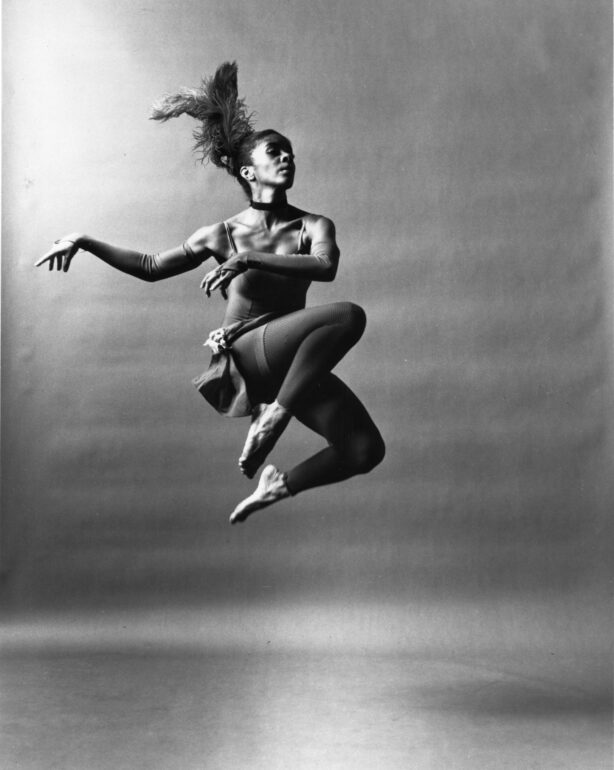

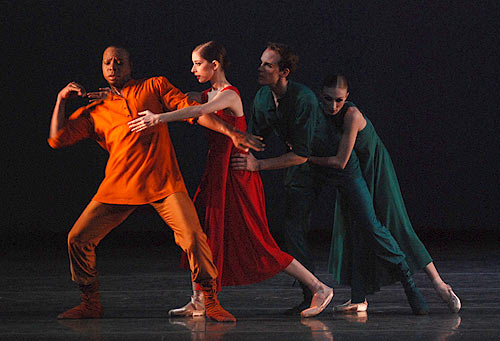

Jamar Roberts’ New Work, Members Don’t Get Weary, for Ailey, Dec. 2017

Kota Yamazaki at Baryshnikov Art Center, with Mina Nishimura, Dec. 2017

Michelle Dorrance Brings New Work to the Joyce, Dec. 2017

Jodi Melnick and Sara Mearns at Works & Process, Jan. 2018

A Blast from Molissa Fenley’s Past at the Kitchen, Jan. 2018

NYCB Reprises Mauro Bigonzetti’s Immigrant Ballet, Oltremare, Jan. 2018

Wayne McGregor’s Genome-Inspired Autobiography, at the Joyce, March 2018

Stephen Petronio Straddles Past and Present at the Joyce, April 2018

The Edgy, Ancient Magic of Meredith Monk, at BAM Harvey Theater, March 2018

Gibney Dance Company at Gibney Space, May 2018

Mark Dendy’s Elvis Everywhere, NY Live Arts, May 2018

What Makes Robbins’ Glass Pieces So Powerful? NYCB, May 2018

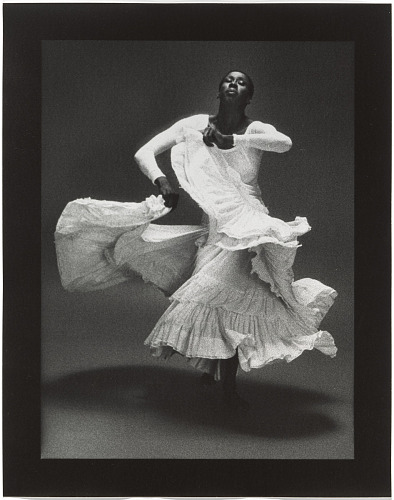

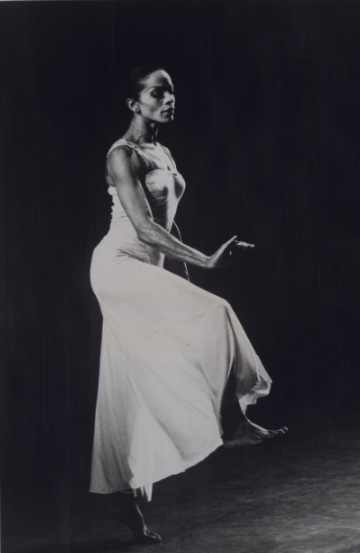

Women Choreographers at Ailey This Week: Jamison and Zollar, June 2018

Ishmael Houston-Jones’ Them, About the Danger and Fears of AIDS, at P.S. NY, June 2018

Tap City’s Rhythm in Motion, Symphony Space, July 2018.

Batsheva Youth Ensemble in Naharin’s Virus at the Joyce, July 2018

Sarasota Ballet Brings 2 Ashton Ballets + Marcelo Gomes to the Joyce, Aug. 2018

Bill T. Jones’ 6-Hour, 3-Part Trilogy at the Skirball, Aug. 2018

Boris Charmatz’s 1000 Gestures at the Skirball, Sept. 2018

The Adrenaline Rush of Tharp’s In the Upper Room, Now Returning to ABT, Oct. 2018

James Whiteside Explores His Creepy Side in Arthur Pita’s The Tenant, the Joyce, Nov. 2018

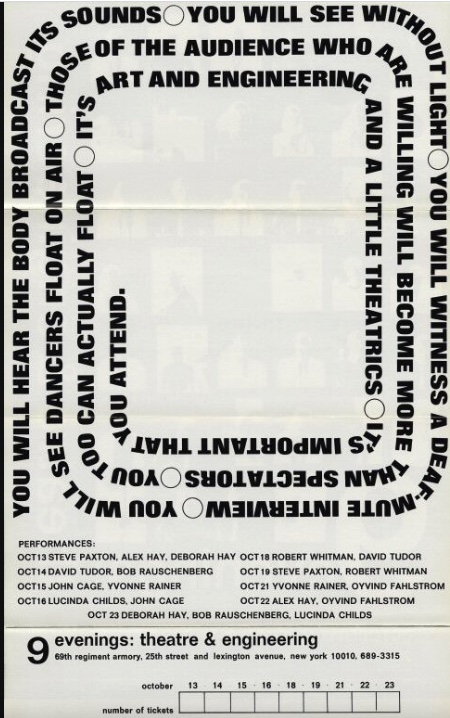

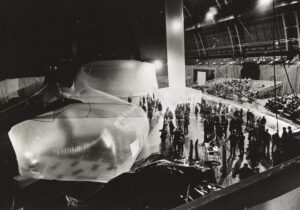

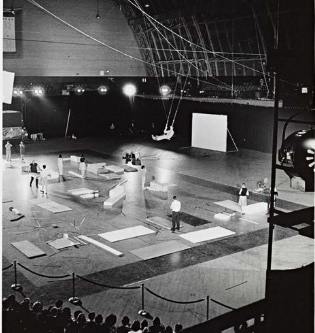

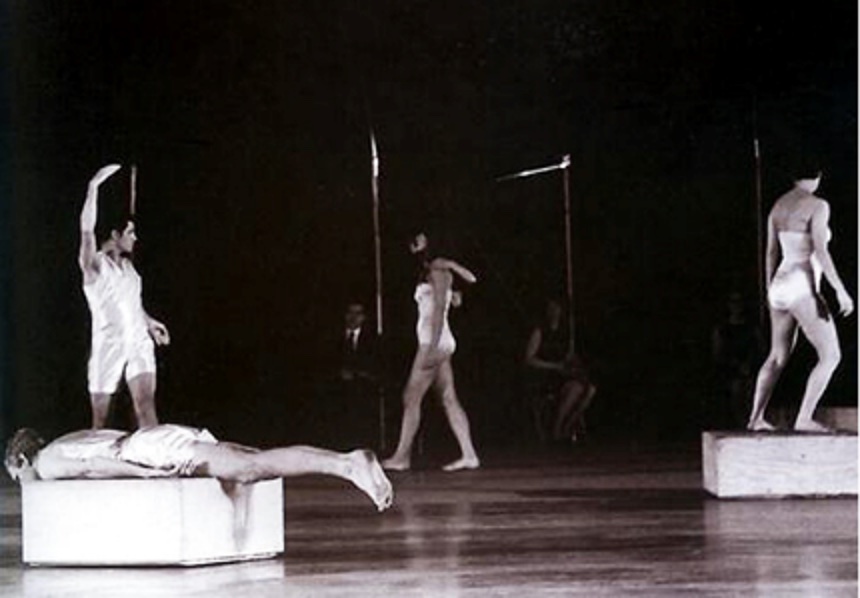

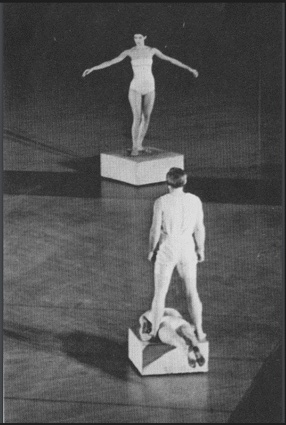

The Judson Revolution Comes to the Museum of Modern Art, Dec 2018–Feb 2019

Featured Uncategorized Leave a comment