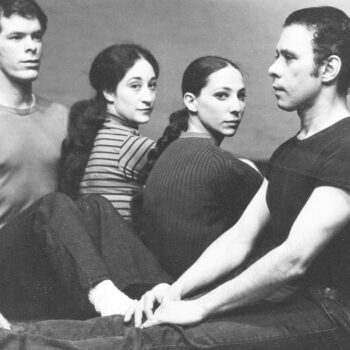

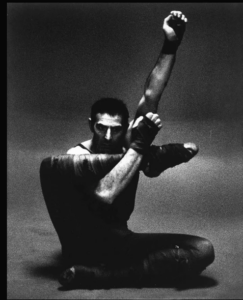

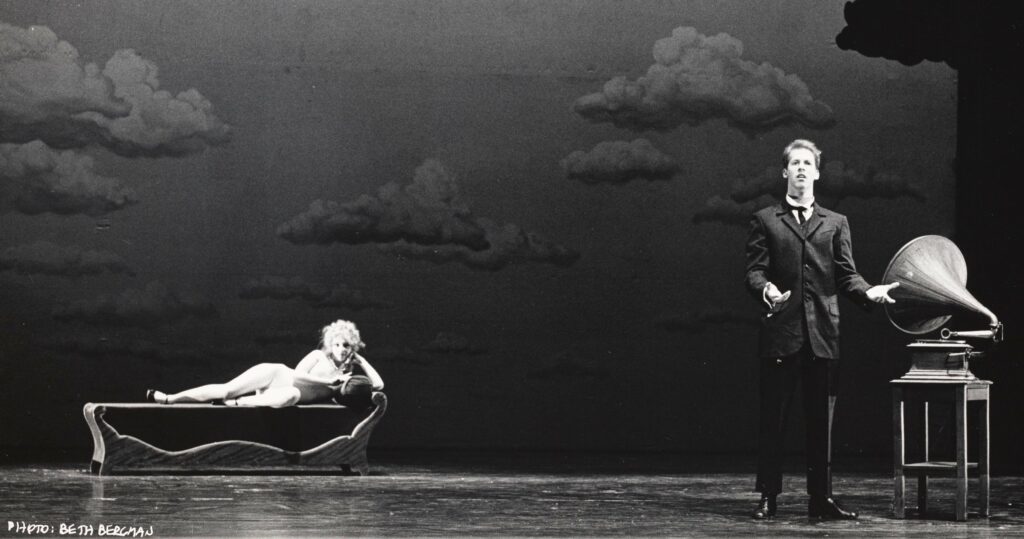

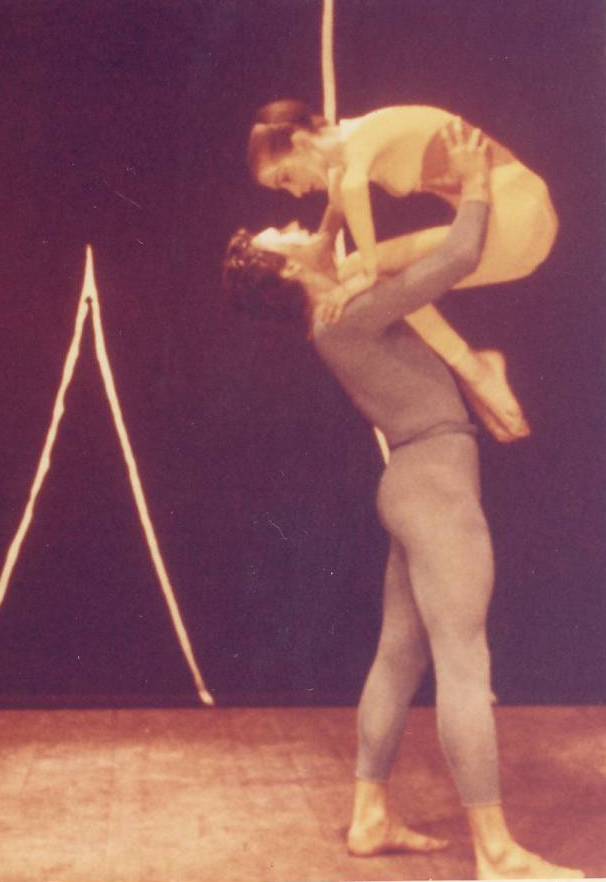

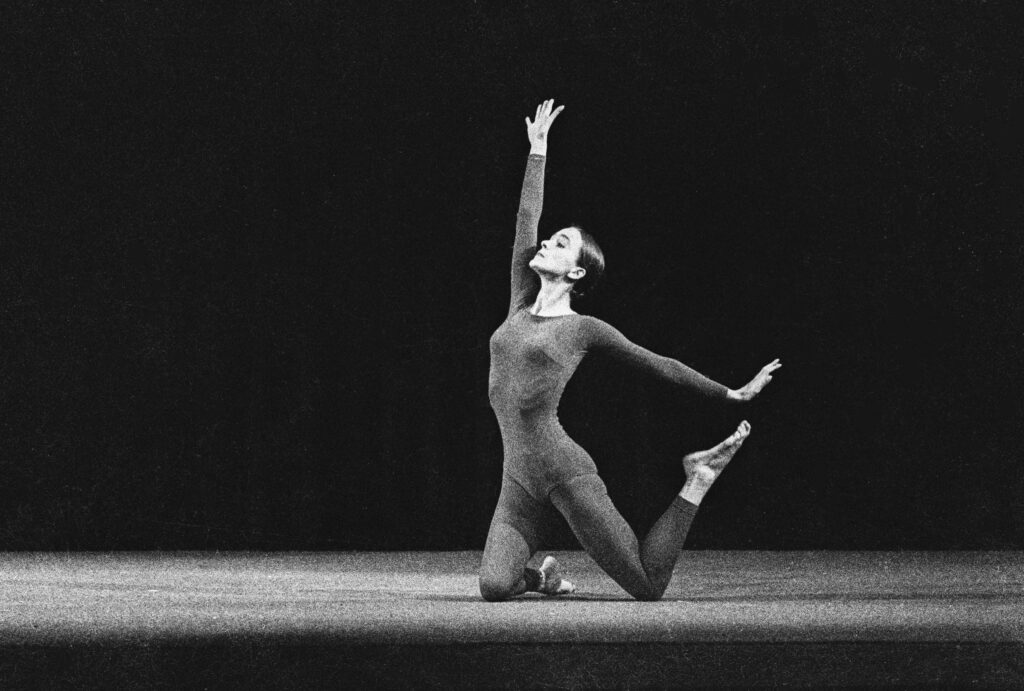

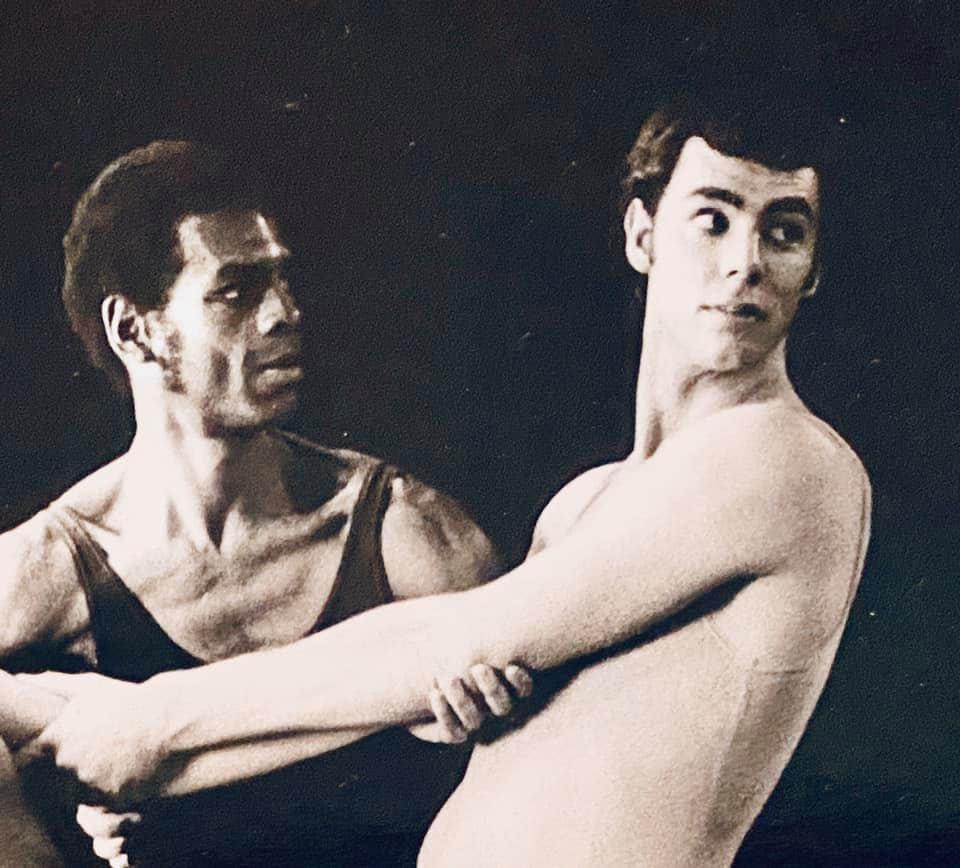

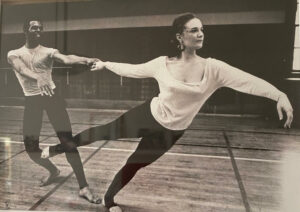

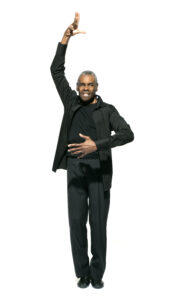

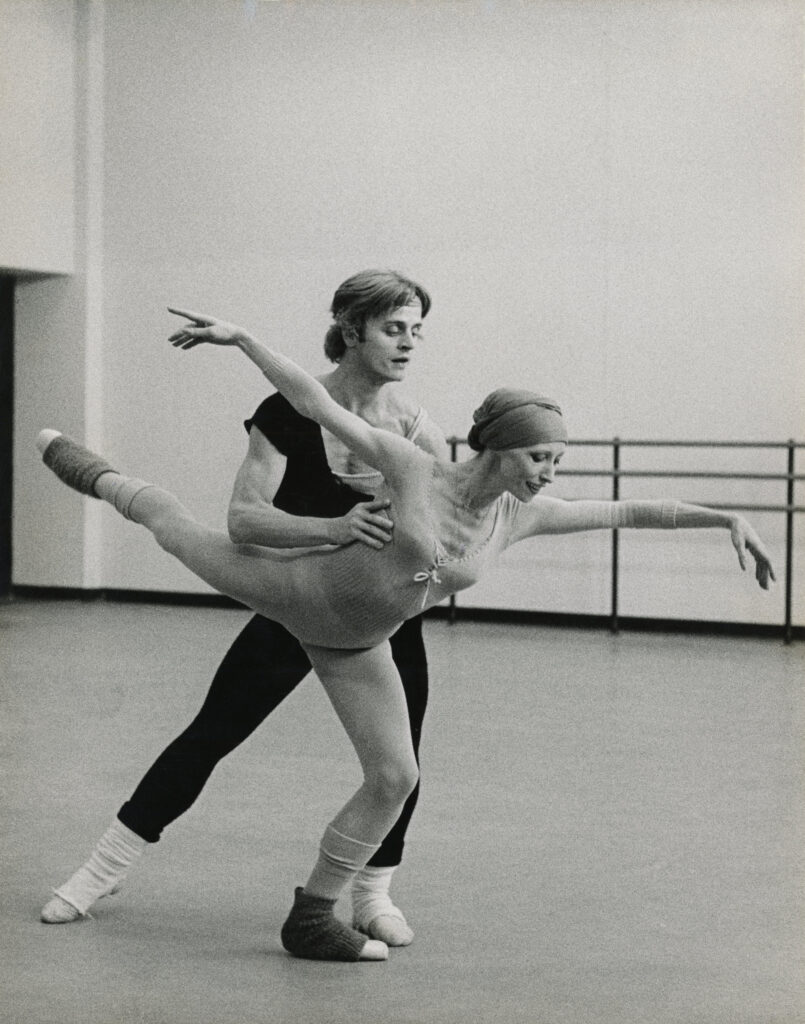

I’m kicking off a new collection of duets in greyscale. For most of these images, I haven’t seen the dance they represent, I’ve just fallen in love with the photo—its composition, its tone, its hint of a relationship. Some of these will look familiar to you, others are more obscure. If you want to know more about a particular photo—or have something to add—please leave a comment below.

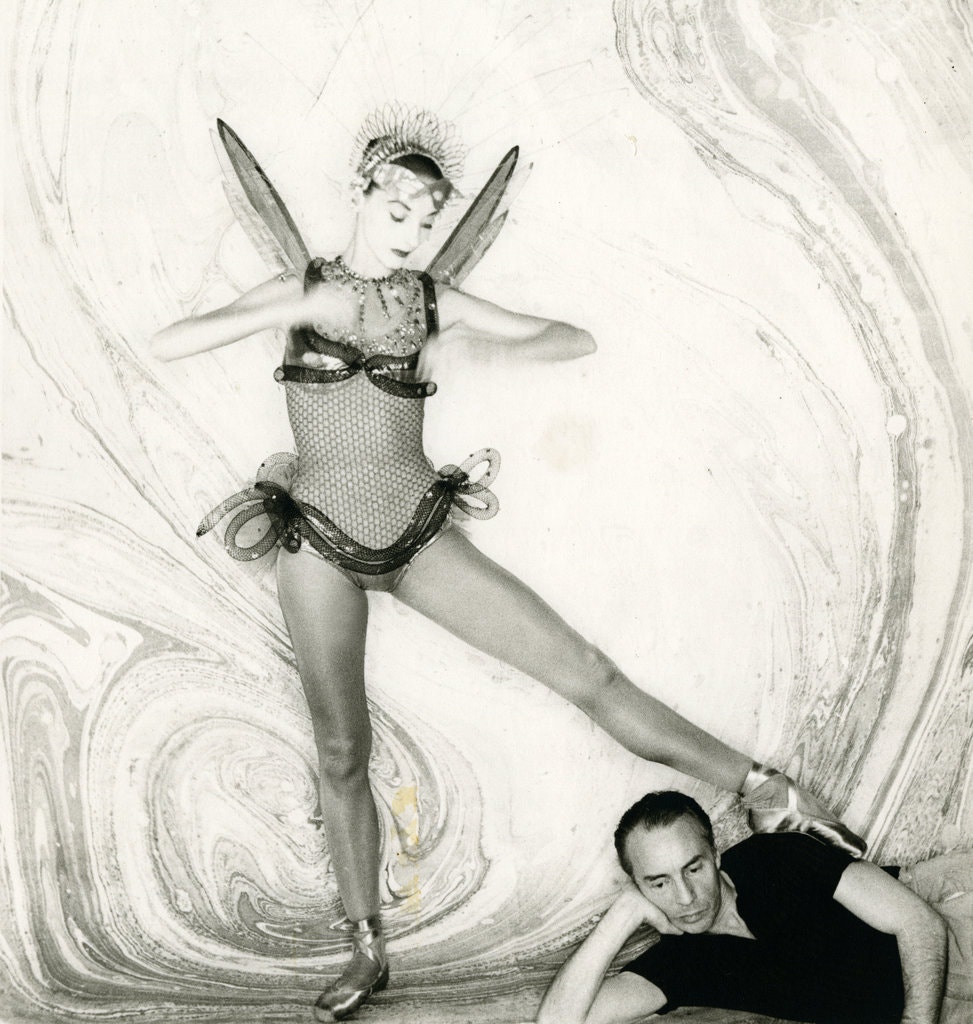

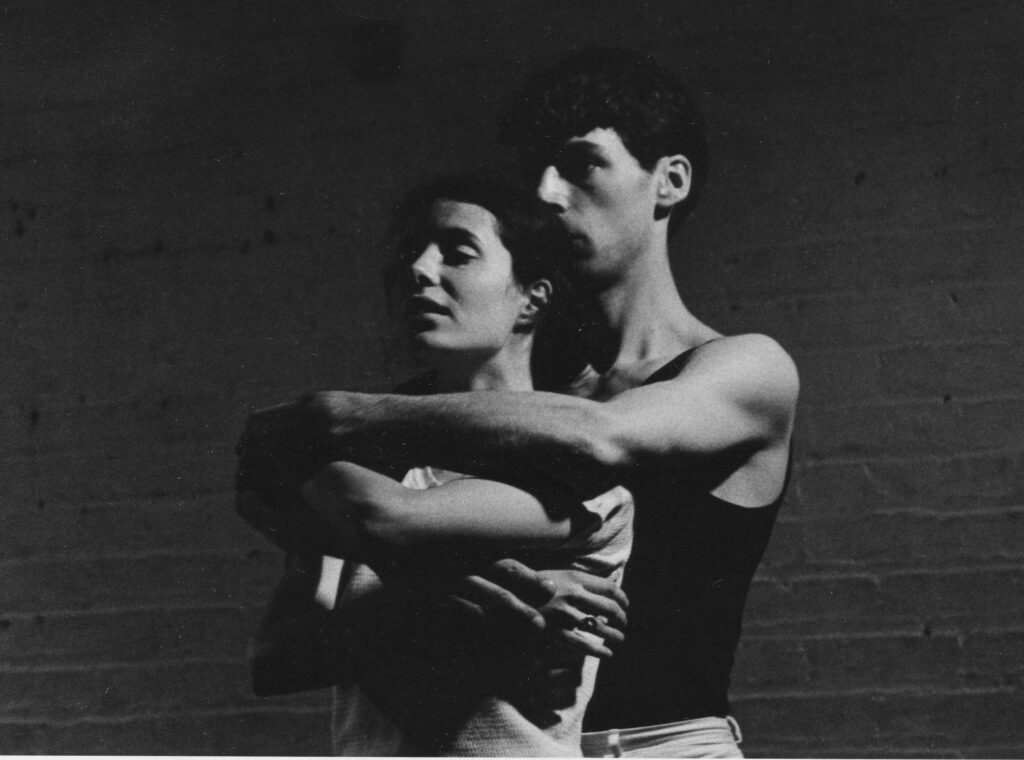

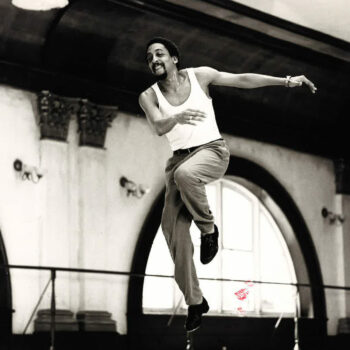

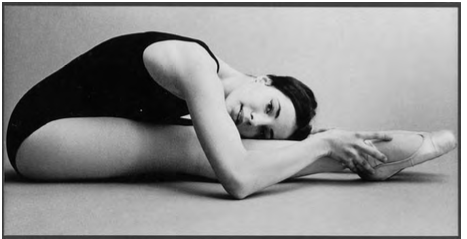

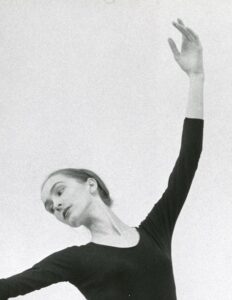

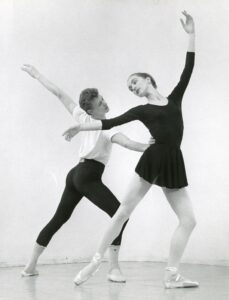

Baryshnikov and Makarova rehearsing Other Dances by Jerome Robbins, 1976, Ph Martha Swope, Billy Rose Theatre Collection

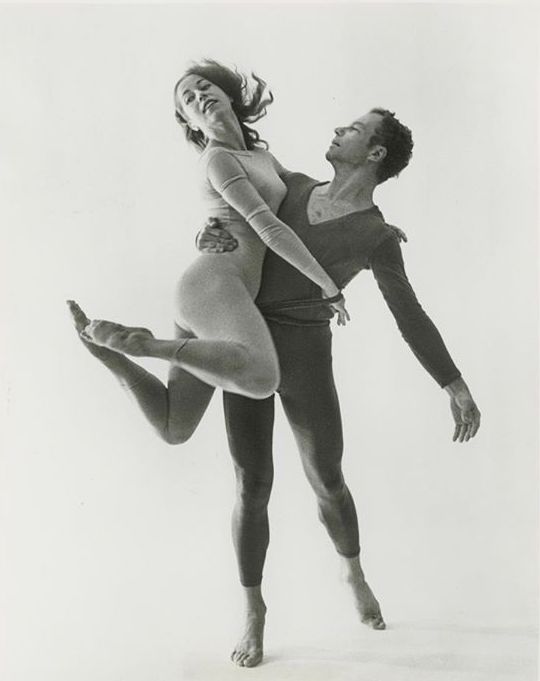

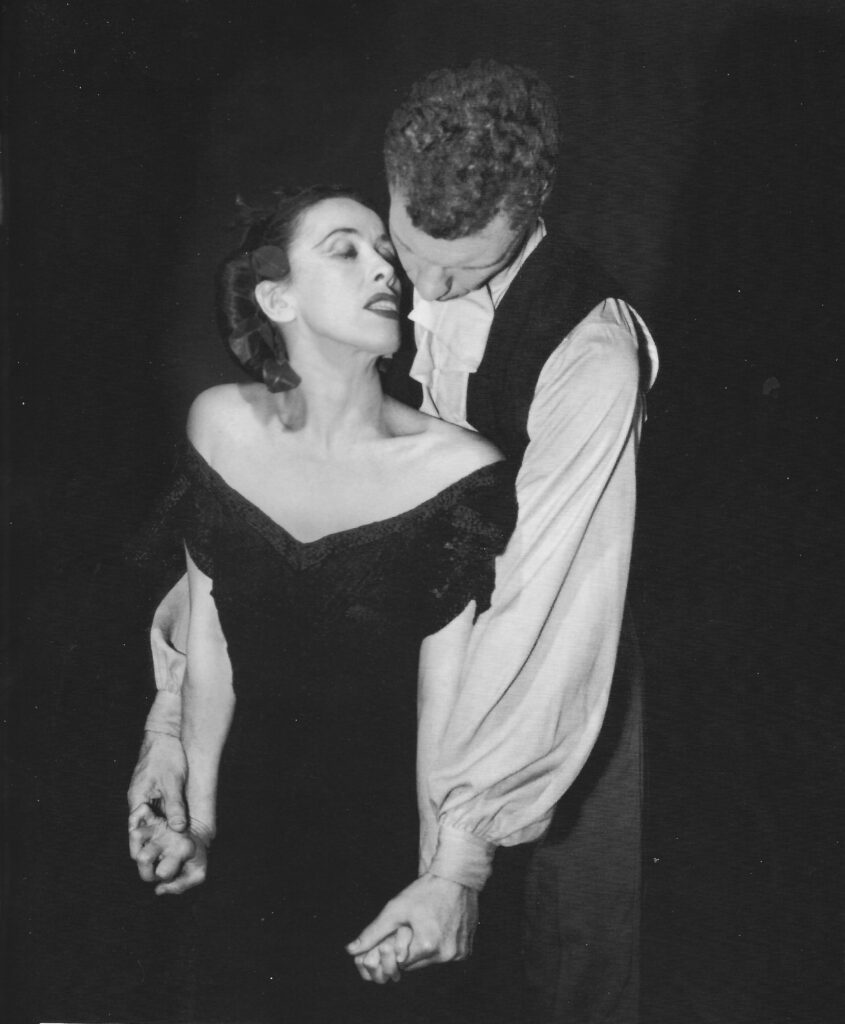

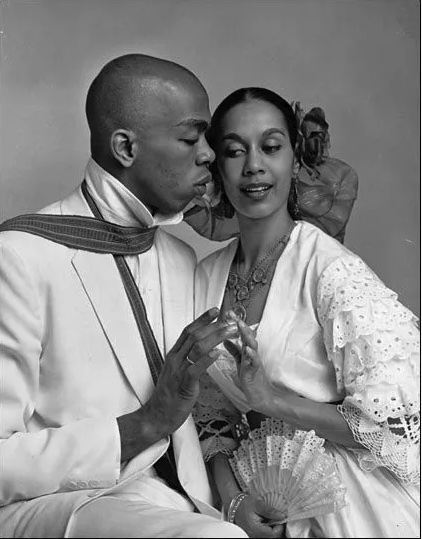

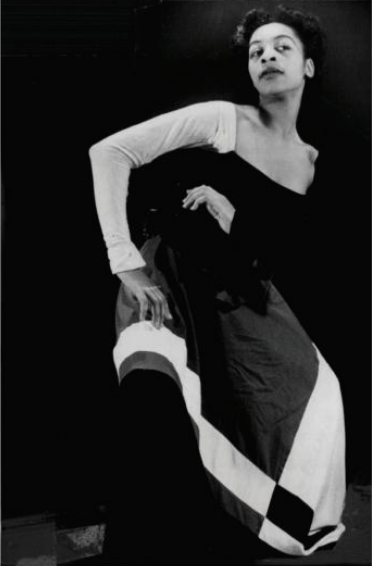

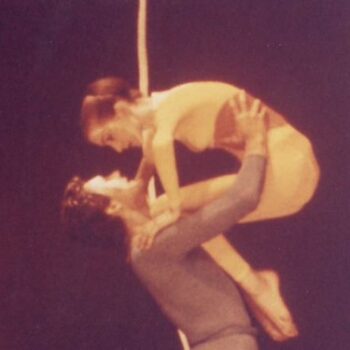

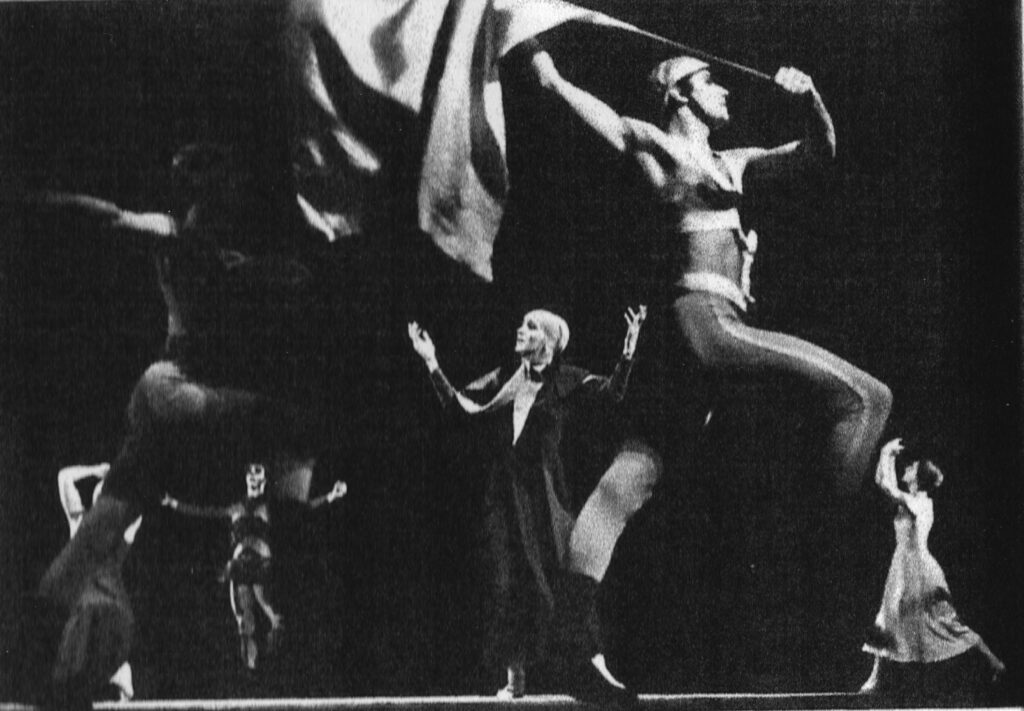

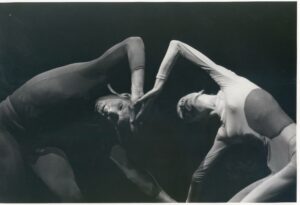

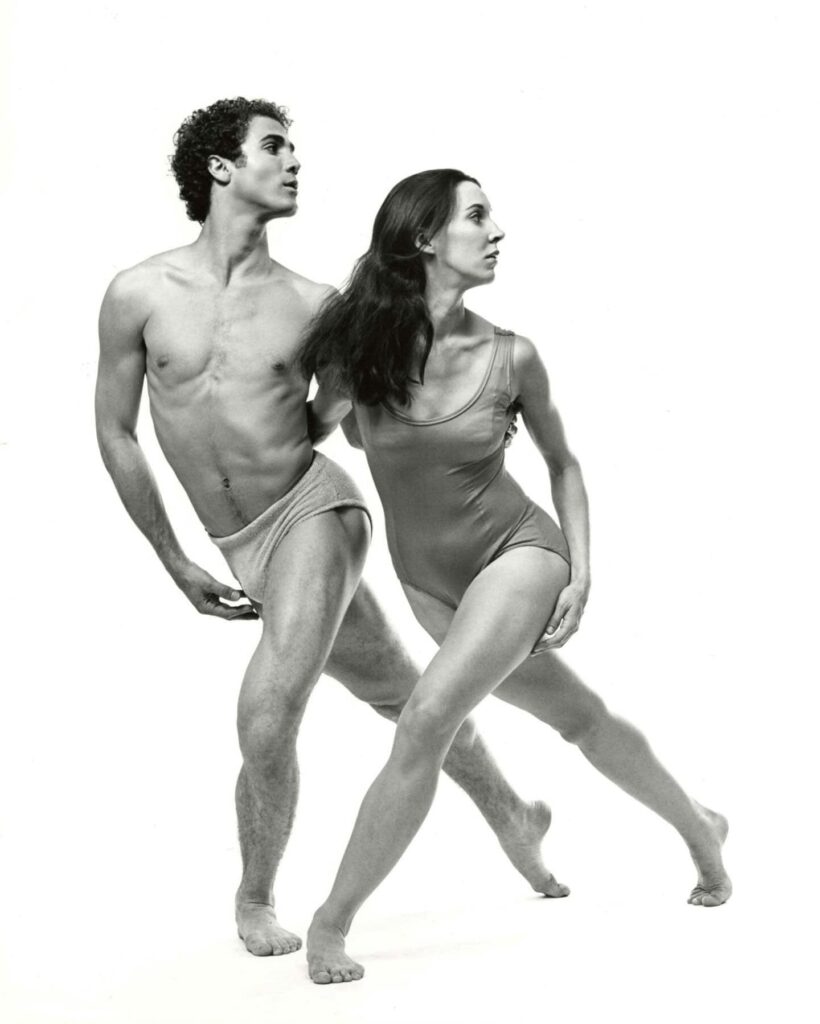

Louis Falco & Sarah Stackhouse in Exiles by Limón, ph Jack Mitchell, Dance Magazine cover, Aug. 1966

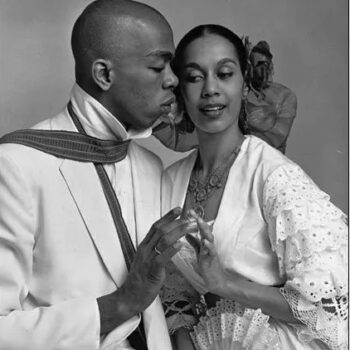

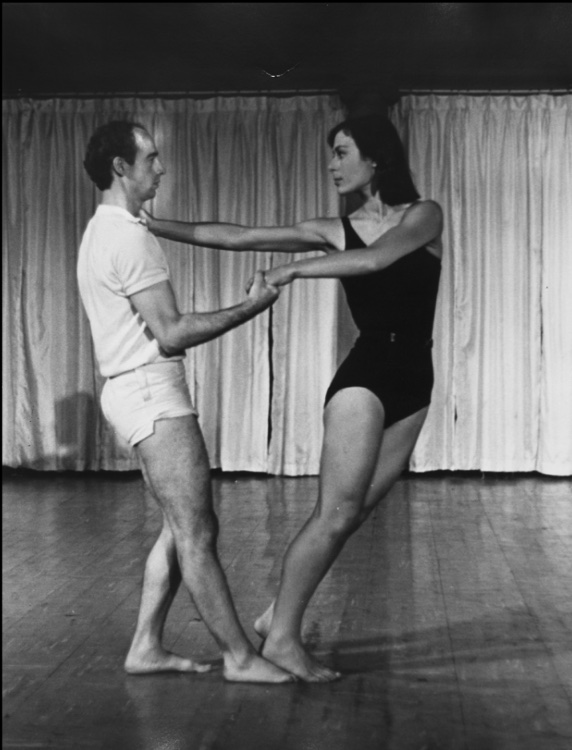

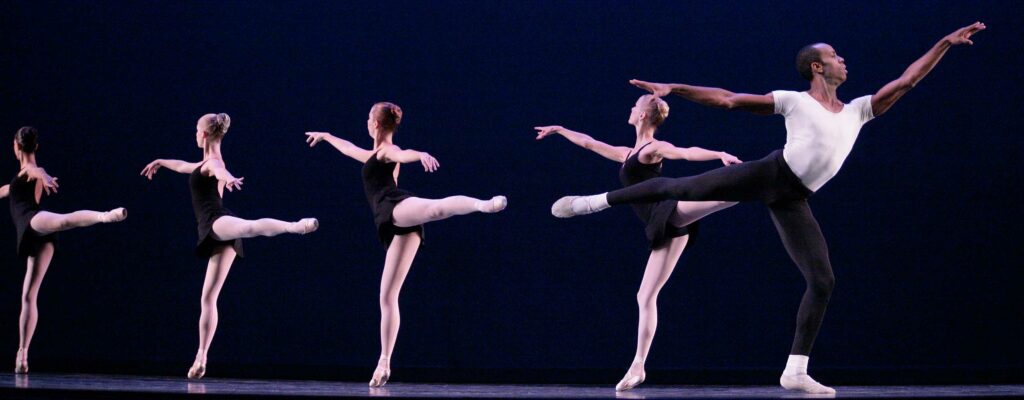

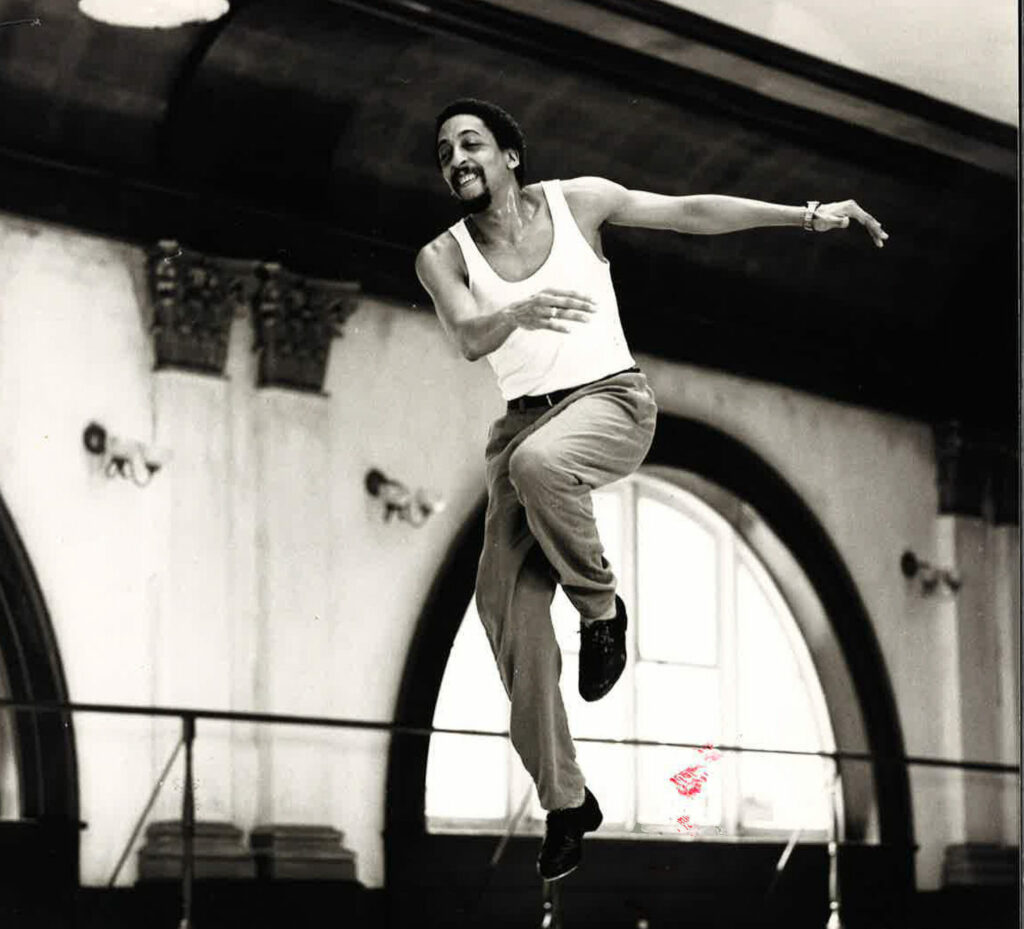

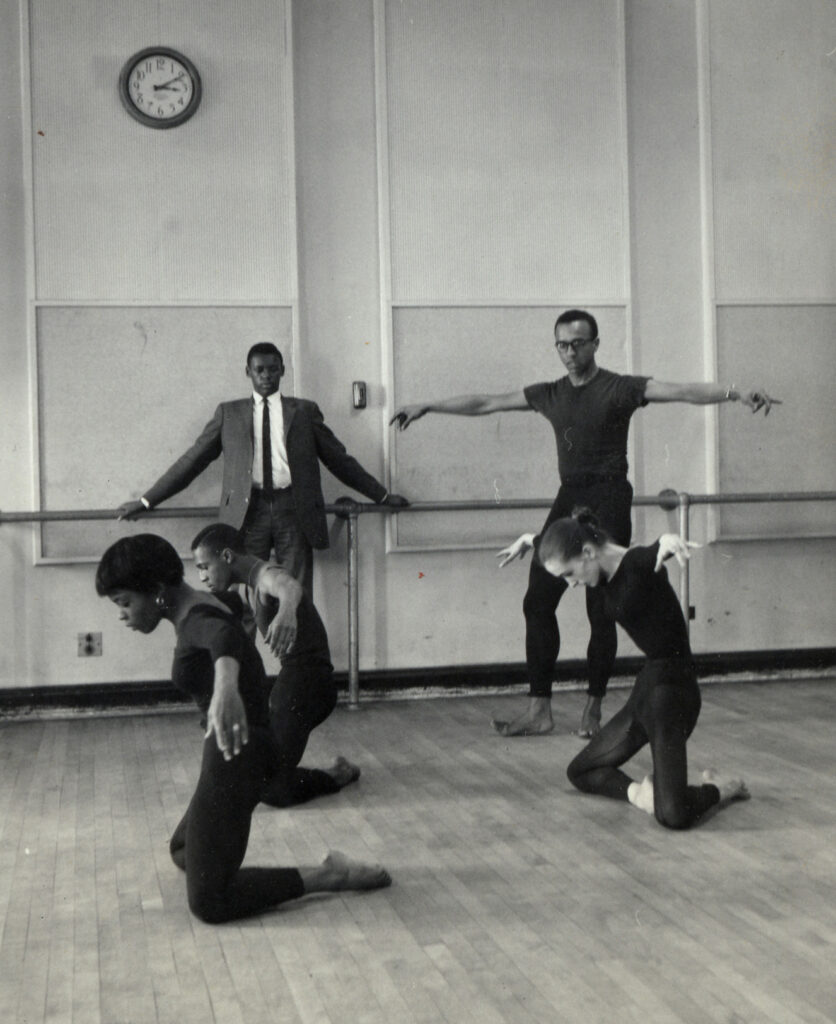

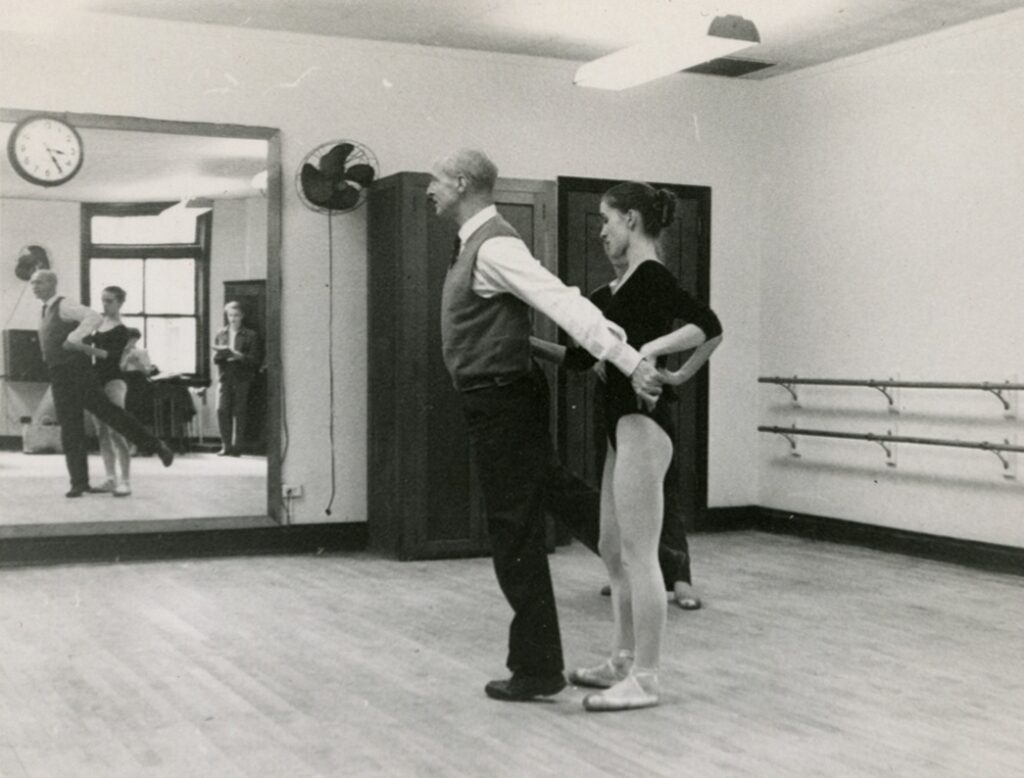

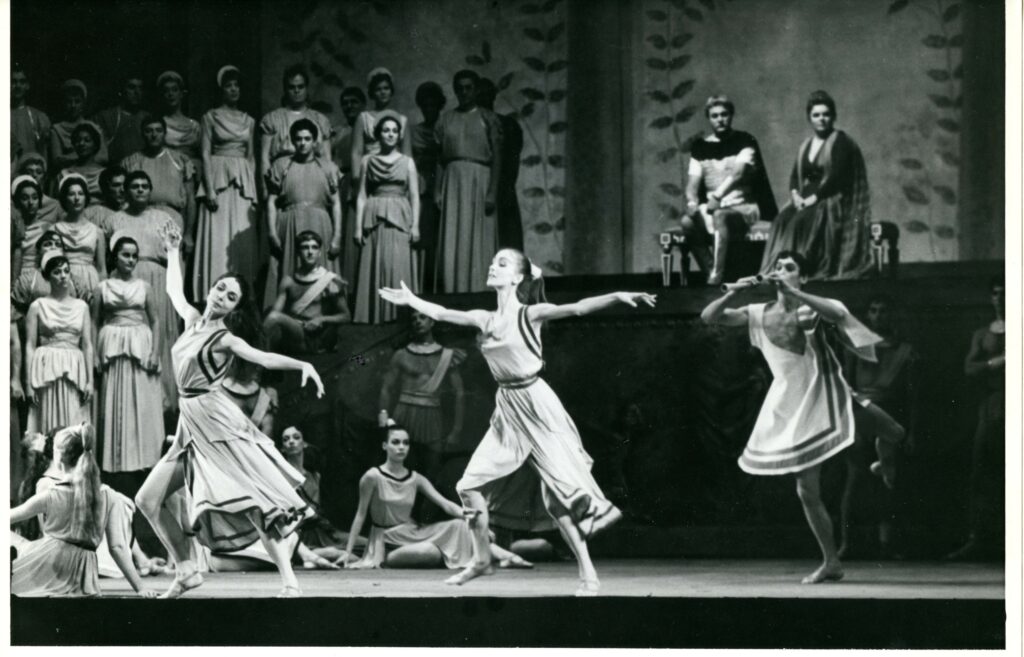

Arthur Mitchell and Diana Adams, Agon by Balanchine, 1957, Ph Martha Swope, Billy Rose Theatre Collection

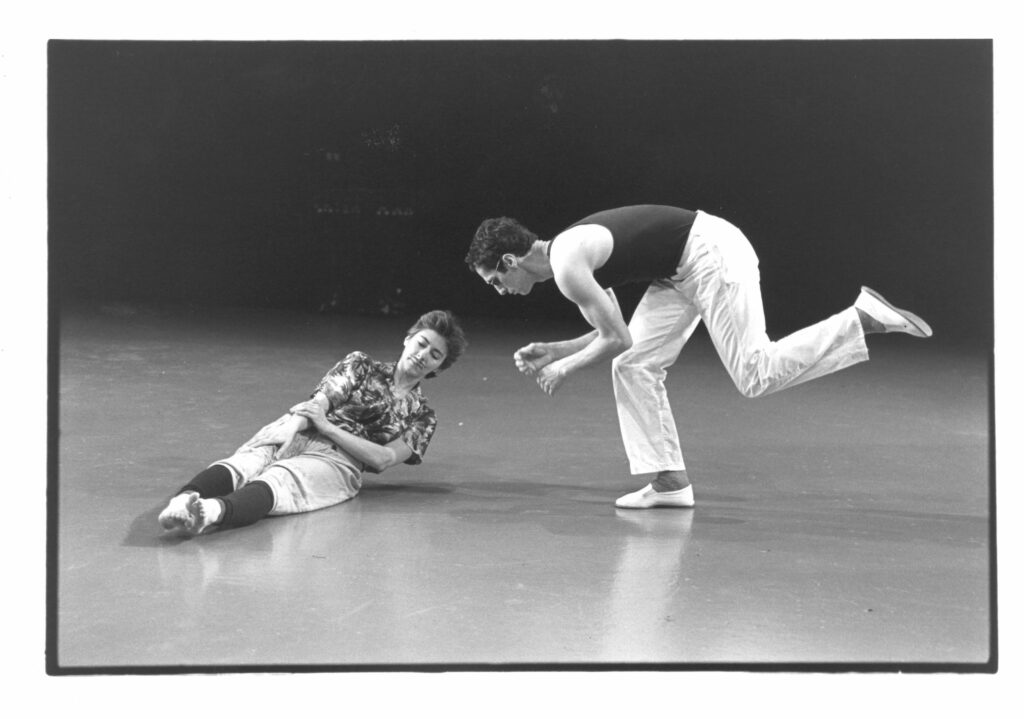

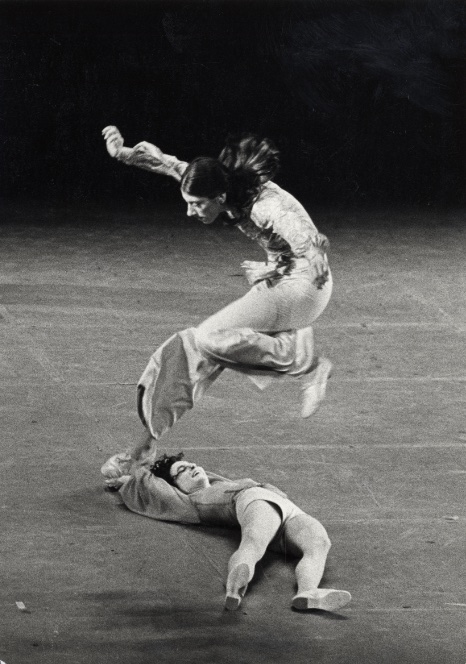

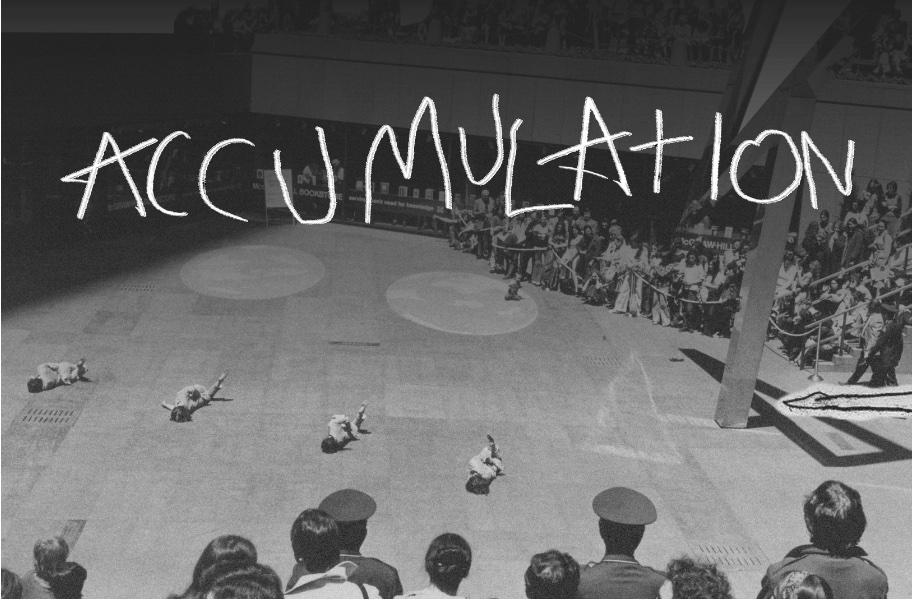

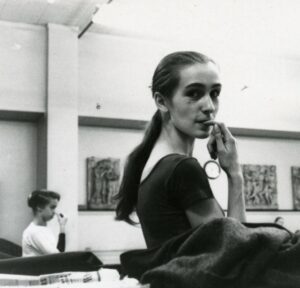

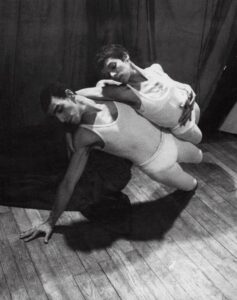

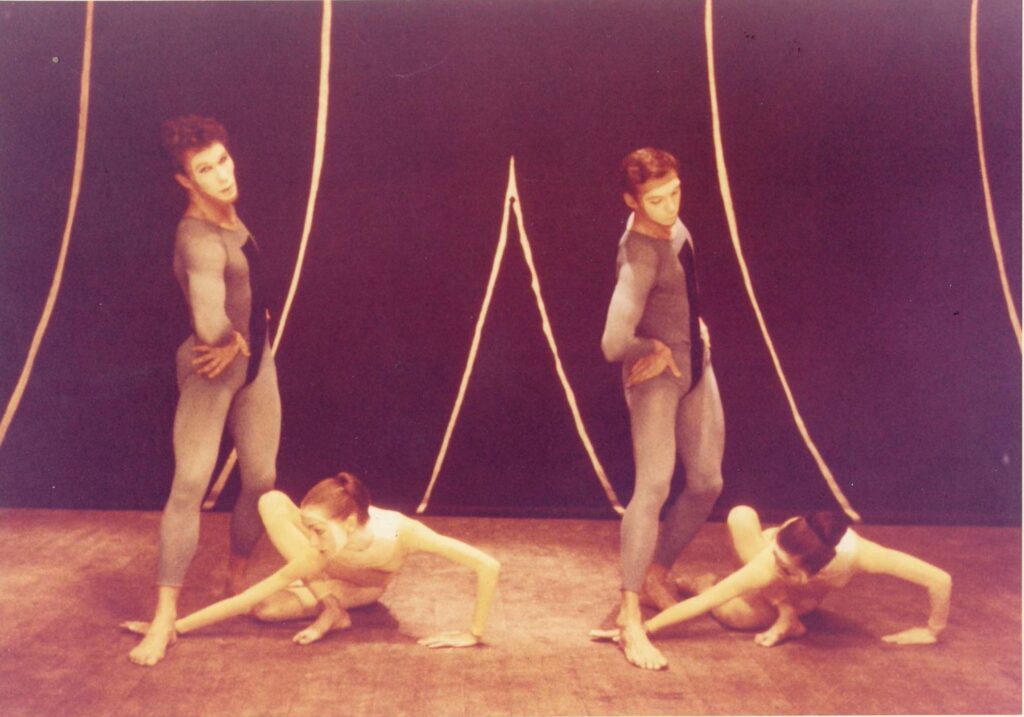

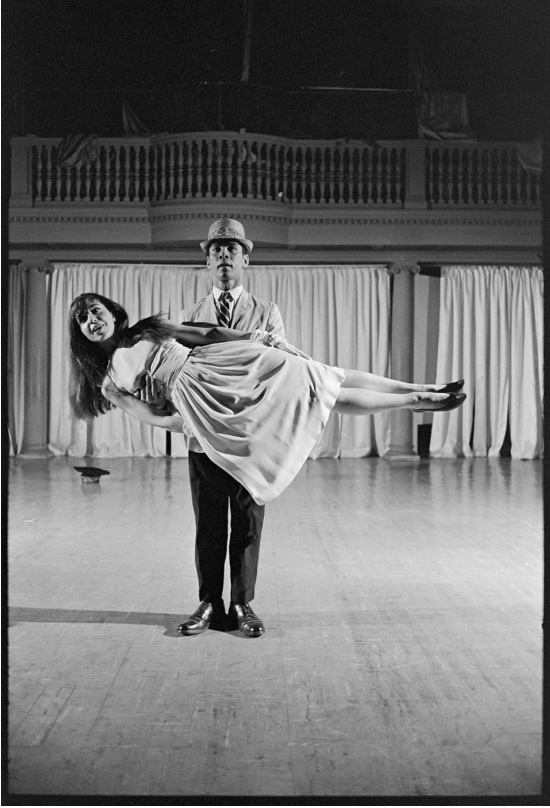

Rudy Perez and Elaine Summers in his Take Your Alligator With You, 1963, Judson Memorial Church, Ph Al Giese

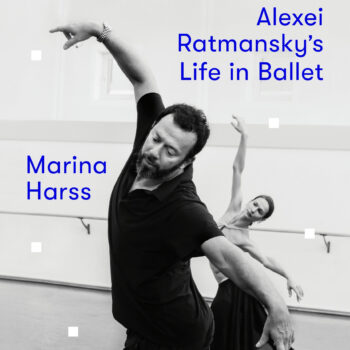

Featured Uncategorized 1