As a judge in any competition, you are expected to be “objective.” But I think there is no such thing as pure objectivity, since we all come to an event with our own set of past experiences. I am aware of my personal biases and try to move beyond them, but part of the value of my—or anyone’s—feedback is in the passionate personal response. And let’s face it, if we know a person from our past, we see more in their performance than if we never laid eyes on them.

This is why the American College Dance Association requires that its adjudicators be kept away from the participants— “sequestered.” All the planners take pains to keep each choreographer’s name and school hidden from the judges so they/we can form opinions on a level playing field.

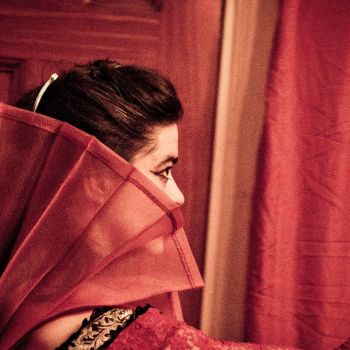

Scotty Hardwig and Breanne Saxton in Eric Handman’s Disappearing Days, photo by Chelsea Rowe

In the West region hosted by Arizona State University, for which I served as adjudicator last week, ACDFA board member Brent Schneider and regional rep Catherine Davalos, as well as ASU organizer Cari Koch, cheerfully accomplished this goal. There were more than 25 schools from California, Arizona, and Utah. I don’t know the West Coast too well, but I do have a number of colleagues at some of these universities. And I admit, if I had known which schools the contestants were from, I might have unconsciously favored them. So I was glad to go into it blind and uphold the frustration of not knowing. (“Endure uncertainty,” wrote Dostoevsky.)

But it does make for a strange situation. First of all, when you’re all staying in the same hotel, you can say hello to the dancers but you are told not to have any more conversation than that. And if they are wearing a sweatshirt with a school name emblazoned on it, you have to avert your eyes. In the feedback sessions, the groups sit together and sometimes it’s obvious what piece they’ve performed.

They are not allowed to ask or answer questions. There’s no discussion, no back-and-forth with the people who showed the work. You can discuss among the two other adjudicators, but you’re all in the dark about identities.

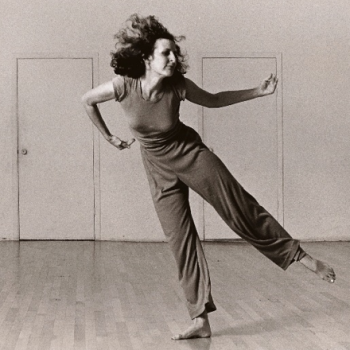

Me, Rachael Leonard, & David Shimotakahara, photo by Lorelie Bayne

The upside of this is that you bond with your fellow adjudicators immediately. You end up hanging out as a threesome and finding connections to each other’s past dance lives. I enjoyed getting to know David Shimotakahara, director of GroundWorks in Cleveland, and Rachael Leonard of Surfscape Contemporary Dance Theatre in Florida. In the feedback sessions, we bounced off each others’ energies. No fireworks in terms of sharp disagreements, but we came to the table with decidedly different slants.

Inevitably, when you finally learn who made which pieces and what school they were from, you realize that some of your hunches were wrong. I thought I recognized a Crystal Pite influence in Disappearing Days and guessed it was made by her former dancer Peter Chu. Lo and behold it was made by Eric Handman, who had danced with me early in his career! Now teaching at the University of Utah, he’s developed an approach called “feral torque” that yields terrifically complex choreography. How did I feel? Surprised and proud.

Another stunner, RUSH, I had figured was the work of a Forsythe disciple, like maybe Helen Pickett, who loves to ricochet between deconstructed épaulement and the ballet vocabulary itself. Wrong again. It was made by Robert Sher-Macherndl for the Dominican University LINES Ballet BFA program. How did I feel? Like I discovered a new program and a new choreographer.

Watching the zany Neanderthal versus Cyborg, I laughed through it while having a lingering feeling that the charismatic female dancer was someone I should know. When she turned out to be Laurel Tentindo, whom I recently danced with in Vicky Shick’s Everything You See, how did I feel? Like I had forgotten what my own home looked like—but also exhilarated to see another side of this magnificent dancer.

And when I learned that the poignant solo-with-talking My Mother and I by Cambodian student Chankethya Chey had been coached by UCLA’s David Rousseve, who has made an art of autobiographical talking solos, how did I feel? Like I should have known all along.

So it’s a guessing game. Frustrating at first but delightful in the end. The payoff wouldn’t have been so filled with surprises if we had known their identities beforehand.

Warming up for the big vote. Photo by David Shimotakahara