Wayne McGregor’s Woolf Works, his first full-length for The Royal Ballet, has been controversial. It’s neither a fairy tale ballet nor an “abstract ballet,” and that can be puzzling. But it does have the McGregor brilliance all the way through—and something more: Alessandra Ferri. Here’s my report from London.

If you could drop the expectation of a linear narrative, you could fully appreciate the dancing, the music by Max Richter, and the astonishing visual elements. You would immerse yourself in light, sound and motion the way Virginia Woolf immersed her readers in words and phrases.

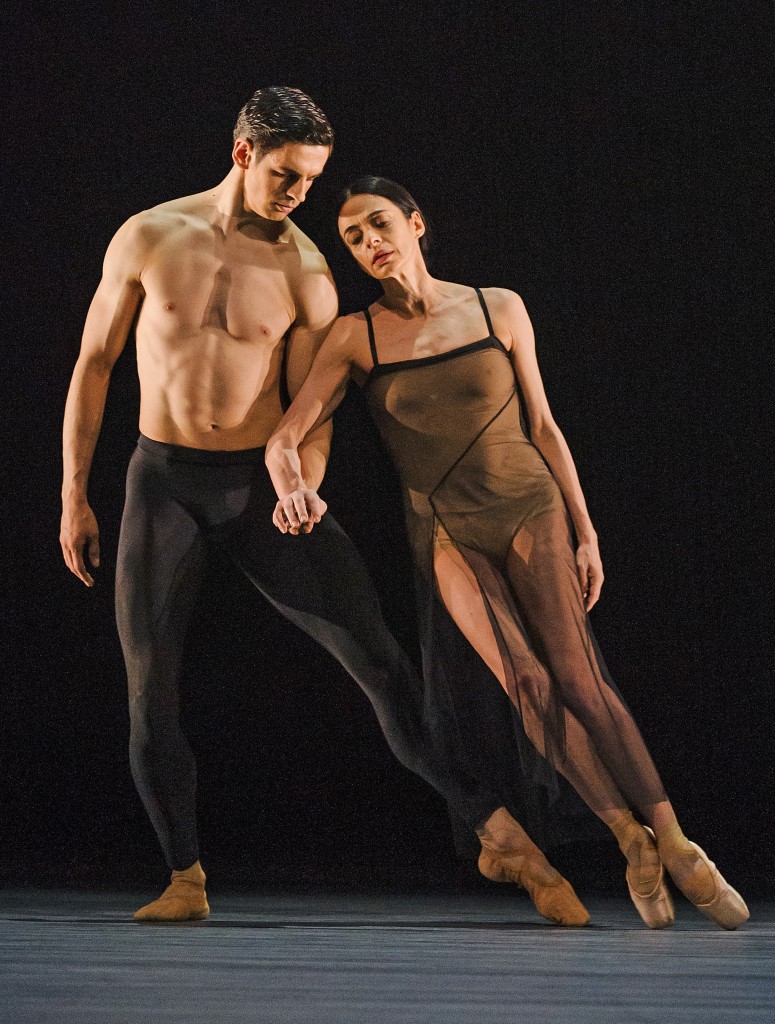

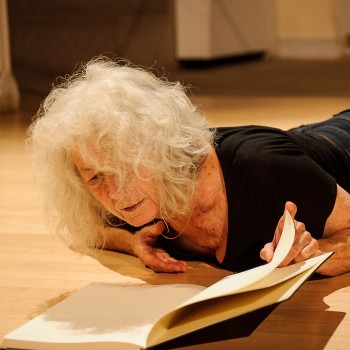

Ferri as Virginia Woolf @ROH, photo by Tristram Kenton

But most of all, you could soak in Alessandra Ferri’s portrayal of this famed British writer. In Dance Magazine’s recent interview with Wayne McGregor about his new full-length story ballet, he said, “She has such a knowing body, that synthesis of amazing acting talent and brilliant physicality.”

First, a brief summary of the ballet: Woolf Works is really three ballets, each based on (or perhaps more accurately “inspired by”) one of Woolf’s novels: Mrs. Dalloway, Orlando, and The Waves. Ferri rules in the first and third sections, and the middle one is pure McGregor, with lashing out kind of dancing between androgynous beings, sans Ferri.

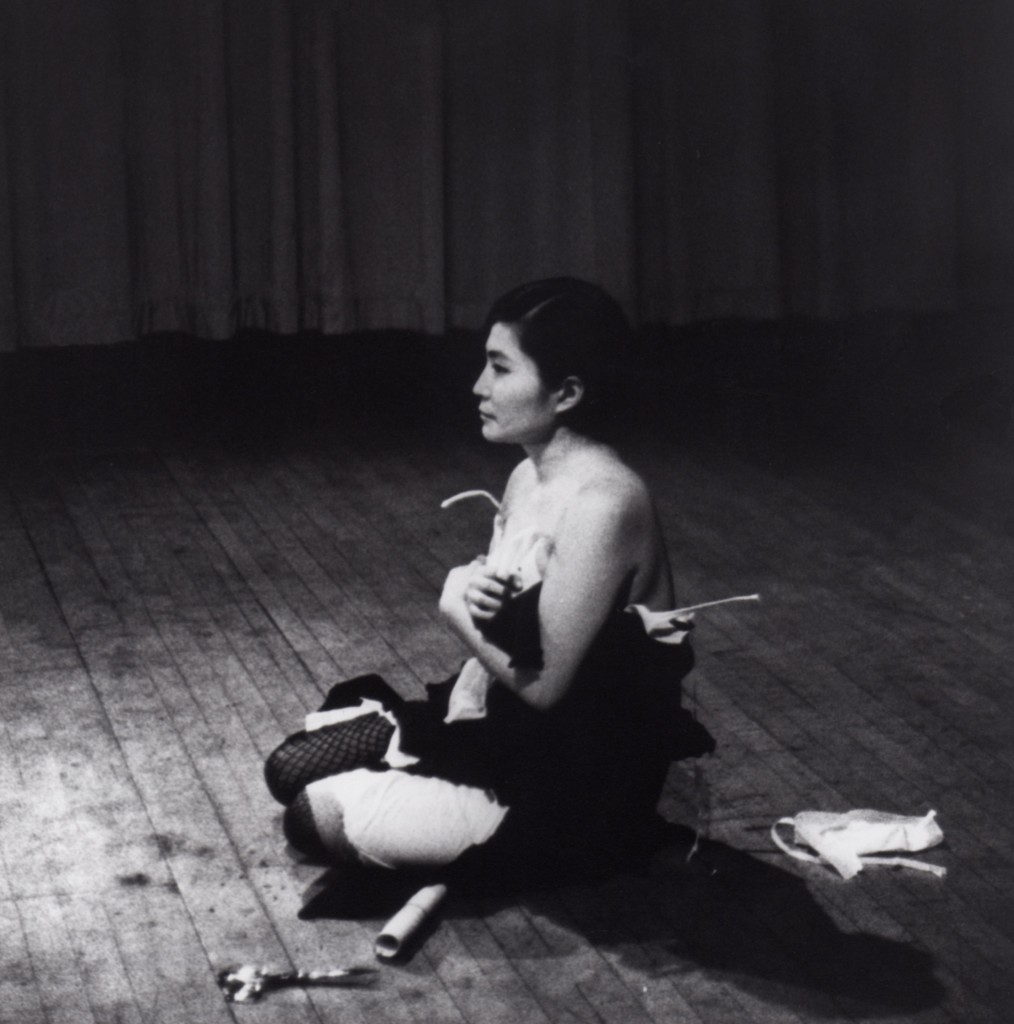

She first appears standing still, center stage. We have just heard Woolf’s voice deliver a treatise on the power of words and seen a scrim full of words flooding in, narrowing into columns and then becoming a fine mist. The scrim lifts and Ferri is revealed, embodying Woolf herself. This section, subtitled “I Now, I Then,” is about her memories; it’s softer in tone than anything I’ve seen of McGregor’s. He is letting Woolf and Ferri lead the way. There is a sweet duet with Federico Bonelli as her husband, and a kiss with a young woman, presumably Vita Sackville-West, with whom she had had an affair. But in general Ferri seems detached from these scenes. [Update 5/26: As you can see from the comment below, I was dead wrong about the characters in this section. I guess I should’ve read up on my Mrs. Dalloway!]

The second section (after a 30-minute intermission, enough time to establish a whole new look) crashes in on us with light beams, thunder, and wild slashing duets. Titled “Becoming,” it takes us through changes of centuries and of genders, with extravagantly gold-hued Elizabethan dresses and ruffs de-composing bit by bit. A projection of fascinatingly etched blue clouds encroaches from stage left while the dancers tilt, twist, push and snake their way through McGregor’s typically aggressive partnering. (My only quibble with the choreography is this: as the music builds, and the costumes drastically deconstruct, and the lights get more preposterously inventive—at one point a huge, tilted sheet of light seems to intrude into the audience—the dancing stays at the same level.)

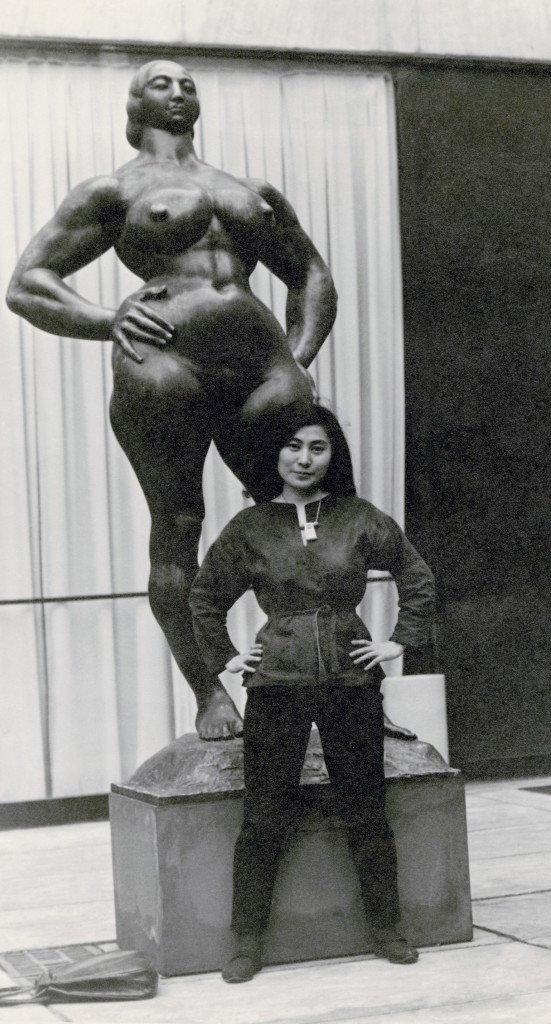

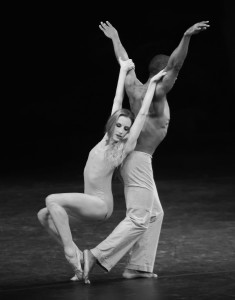

Last section with Camille Bracher, Marcelino Sambé, Sander Blommaert ©ROH, Photo by Tristram-Kenton

By the last section, subtitled “Tuesday,” we are happy to have Ferri back. But it’s clear that we are at the end of Woolf’s life. We hear a voice speak the words of her suicide note. She loves her husband, has had a happy life, but is plagued by her “disease”—which could only mean her suicidal depression. A huge black-and-white photo of waves hangs in the upper reaches of the stage space. But wait—it’s not a still shot but a video of slow-moving waves. We know they will eventually swallow her up, as is her wish. Two by two, the other dancers ebb downstage and flow upstage. The projected waves move a bit faster as Bonelli dances a melancholy duet with Ferri, finally lowering her down, beneath the now roiling waves.

For me, the last section was the most moving because it was emotionally the clearest—and saddest. But in both the first and third sections, Ferri held me in her thrall. The elegant way her head sits atop her spine, looking around with a soft alertness, seemed just right for this literary figure. Although Ferri is known for her outsized passion in roles like Juliet, Manon, and more recently Lea in Martha Clarke’s Cheri, in McGregor’s ballet she plays a woman whose passion is for words—and for death. When she extends that beautiful foot toward the ground, she isn’t displaying her exquisite lower limbs; she’s indicating what she wants to focus on. A simple tendu becomes like a pen set toward paper.

McGregor said, in that same interview, that he chose Ferri because he knew he would learn from her. I think he may have learned about simplicity. With a turn of her head or a leg pointed toward the floor, she expresses a lifetime of experience—her own as well as the character’s. In a ballet that’s more about mood than a clear story line, that’s a lot.

Featured 2