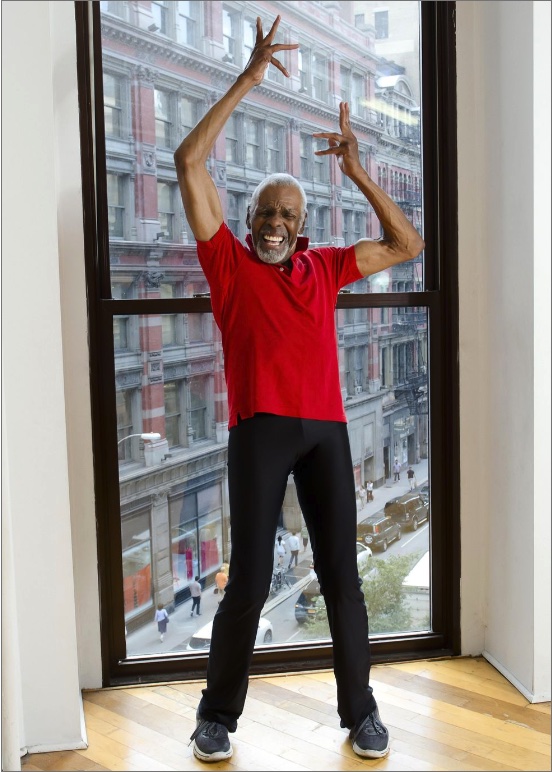

Striking performer. Adventurous choreographer. Unforgettable teacher. Straight-from-the hip-reviewer. Inspiring mentor. Gustave Martinez Solomons jr was all these things and more. With boldly energetic dancing, a Hollywood face, and a ready laugh, Gus seemed comfortable in any dance genre. His fluidity between the largely white postmodern community and various dance communities of color was a healing balm in these times of bifurcation. He was beloved by people in all these factions, so it’s no wonder that, since his passing on August 11, messages of love and gratitude have come pouring in on social media. He’s been called a legend, dreamboat, amazing artist, and earthly angel.

Born in Cambridge, MA, Gus briefly took tap, acrobatics and ballet lessons in a local studio. In high school he performed with the Boston Children’s Theater and other community groups. As an architecture student at Massachusetts Institute of Technology, he moonlighted by studying dance with Jan Veen, the German Expressionist émigré who founded the dance program at Boston Conservatory. When he told one of his professors at MIT that he wanted to be a dancer, the reply was, “Oh no, you’ll be a credit to your race if you become an architect!” (Source: The History Makers.)

Guest artists came to teach at Boston’s Dance Circle, and one of them was Donald McKayle, Remembering Gus from class, McKayle invited him to New York for a musical that was dead on arrival—but Gus’s professional life in dance was born. He quickly picked up gigs not only with McKayle, but also with Pearl Lang, Joyce Trisler, and Paul Sanasardo. And yes, Martha Graham.

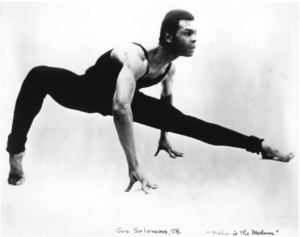

Gus loved to jump and said he could “hang” in the air. McKayle witnessed that skill firsthand in his own work Legendary Landscapes (1963): “There were… phenomenal aerial moments with Gus Solomons jr suspended in space above the female ensemble.” (Source: McKayle’s memoir, Transcending Boundaries)

In the early 1960s Gus was part of a studio-sharing cooperative called Studio 9, with Elizabeth Keen, Phoebe Neville, Cliff Keuter, Elina Mooney, Kenneth King, and others. He attended some of the sessions in experimental dance-making that Robert Dunn led at the Cunningham Studio, and he enjoyed using chance method inspired by John Cage. But he was “too in love with technical dancing” to get involved in the pedestrian aesthetic of Judson Dance Theater, which emerged from Dunn’s workshops. Not to mention he was already getting paid gigs with more established companies.

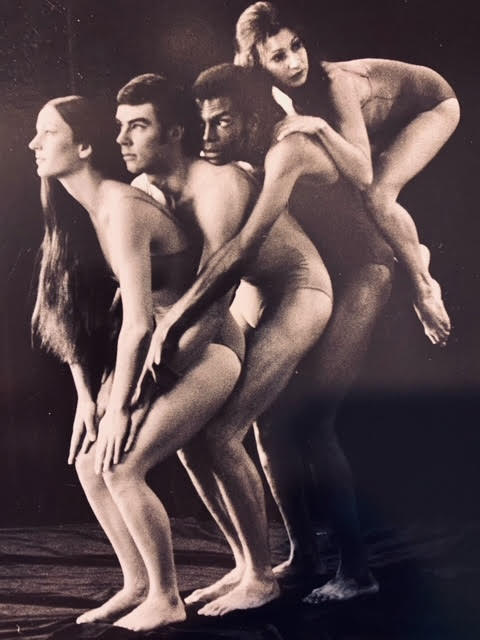

Gus found his aesthetic home in the Merce Cunningham Dance Company, where he danced from 1965 to ’68. There he could just dance—leap, lunge, crawl, pivot, skitter, and extend his space-piercing legs. He originated roles in key Cunningham works: How to Pass Kick Fall and Run, RainForest, Place, Walkaround Time, and Scramble. After three years, a back injury forced him offstage temporarily. (For an excellent interview on his thoughts about Cunningham, see Mondays With Merce #14.)

In the late ’60s, Gus formed his own group, the Solomons Company/Dance, for which he choreographed more than 100 pieces. Taking an analytical approach, as per his architecture training, he made charts, designs, and diagrams and explored alternative spaces. Although many works had no music—or just the invited sounds of the audience coughing and rustling papers, as in Kinesia #5 (1967)—he sometimes collaborated with composers such as Mio Morales or Toby Twining. He embraced the new technology of video, creating an ingenious use of a dual screen for City/Motion/Space/Game in 1968 at WGBH-TV in Boston. His 1986 “interactive dance/sound/video system” titled CON/Text was performed at Just Above Midtown.

Touring in the 1970s gave the Solomons Company/Dance full-time work. Many residencies, funded by the National Endowment for the Arts in conjunction with various artists-in-the-schools programs, required all company members to teach. The group became experts at adapting to all kinds of situations.

A watershed moment came in 1982, when Ishmael Houston-Jones brainstormed Parallels, a series for Black choreographers outside the Black mainstream of modern dance, at Danspace Project in downtown New York. Solomons, along with Ralph Lemon, Bebe Miller, Blondell Cummings, and Harry Sheppard, were invited to show their work. As Gus wrote for the 2012 reprise, he was glad to be included “instead of being criticized for not being ‘black enough’ as I often was back then.”

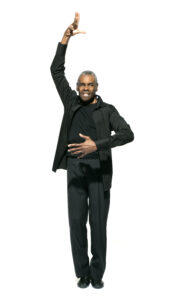

In 1996 Solomons founded Paradigm, a small group celebrating the artistry of older, seasoned dancers. The kickoff was A Thin Frost (1996), a trio Gus made for himself, Carmen de Lavallade, and Dudley Williams. This gem of a dance had moments of solemnity, wistfulness, and hilarity, where all three stars could revel in being themselves before finally reaching for a communal touch. Paradigm commissioned other choreographers, including Kate Weare, Robert Battle, Jonah Bokaer, and Wally Cardona. A glorious example of a guest work is Dwight Rhoden’s It All, for Solomons and de Lavallade. This was a moving, haunting duet to music by Björk, an excerpt of which, happily, is caught on video by Jacob’s Pillow.

Carmen de Lavallade and Gus in It All, by Dwight Rhoden for Paradigm, ph Marta Fodor via Ken Maldonado.

Solomons was a demanding but nurturing educator, teaching at UCLA, UC Santa Cruz, CalArts, Bard, and—for many years—NYU’s Tisch School of the Arts. His studio in Lower Manhattan was abuzz with his own classes as well as with rehearsals of dancers renting the space. In 2004, he received American Dance Festival’s Balasaraswati/Joy Ann Dewey Beinecke Endowed Chair for Distinguished Teaching. And the Bessie Awards honored him with Sustained Achievement in Choreography in 2013. The following year the Jerome Robbins Dance Division at the NY Public Library for the Performing Arts named him a Dance Research Fellow in its inaugural year.

Solomons has served as choreographic mentor at Dance New Amsterdam, The Ailey School, and NYU/Tisch and given informal advice to many others. He’s lent his performing self to younger choreographers, including Donald Byrd, Johannes Wieland, and John Heginbotham.

Always nimble with words, Solomons wrote reviews and features for Dance Magazine, as well as for the Village Voice, Ballet News, Attitude, andThe Chronicle of Higher Education. In recent years, he posted reviews and reflections on his own website, Solomons-Says.

He also used words to advocate for himself. In 1983, Gus was not invited to participate in Dance Black America, the historic gathering at Brooklyn Academy of Music. He felt slighted and wrote this letter to the planners:

I have spent twenty years making dances that stem from my honest experience and my perceptions of dance as an expression of energy-as-motion, not as a vehicle for the expression of racial anger or social oppression, which, fortunately do not happen to be part of my personal background. It saddens me to realize, if indeed it is the case, that my work is apparently being ignored by my Black colleagues because it refuses ethno-cultural categorizing. (Source: The Black Tradition in American Dance by Richard A. Long)

Because Gus’s contribution was so huge, I’ve asked a few dance artists who worked closely with him for their memories:

Douglas Nielsen, member of Solomons Company/Dance, 1973–75, and friend for life

Gus was like a coffee pot that never stopped percolating. He was a source of infinite possibilities. Articulate to the core. He was a director with a purpose. Always prepared, and always in step with the times. His choreography was clear and nonnegotiable: ‘This is what it is. Now do it.’ He often showed it, physically, but he also had prepared a movement score on graph paper for reference.

Gus was a role model. I am 6’4”, and so was he. He taught me how to move fast in space. Not to music, but with an inner non-narrative motivation. We did a duet called Prance Dance (1974), with extremely fast footwork in unison. It was like a race against the clock. I still remember every bit of it. The challenge was to stay focused, be precise, and be in the moment. Gus never gave us notes after a performance. We knew what might’ve gone wrong, and we knew how to correct it.

Gus lived his professional life as a man free of labels. He never defined himself by race, gender, or sexual orientation. When I asked him about that, he simply said he was “oblivious.” Truly an original.

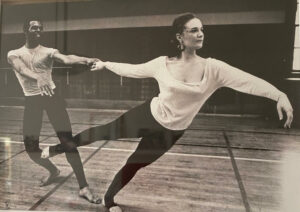

Margaret Jenkins, artistic director, Margaret Jenkins Dance Company

Gus and I started working on simply this fondness in 1964. I had met him when he came to teach a workshop at UCLA. He said, “Come east and let’s work.” I did. His long legs and my long torso became the “subject” of the work—how to find the balance between the two. He pushed me to lean into risk. He taught me how to trust I would be caught. He was fierce in his demand. He was kind with his physical support. There was joy, aways joy, close by.

Larry Keigwin, Artistic director, Keigwin + Company; producer of the short film #sharethemattress—Gus Solomons jr.

Not only was Gus a mentor and friend, but he was also quick to dance for our camera when I asked him to participate in our video project Share The Mattress. It was a delightful and intimate afternoon. Gus gladly invited us into his bedroom and with cheer and vigor improvised for our camera. He didn’t need much direction….his physical instincts and dramatic intentions were spot on. Sensitive and self deprecating (in a good way) he kept us laughing with clever conversation and witty quips. It was pure joy.

Donald Byrd, Artistic director, Spectrum Dance Theater; member of Solomons Company/Dance, 1976–1978

What struck me about Gus was how thin he was, how long his limbs were, and that he was Black in what was often a very “white” context. I felt an affinity. The performance I saw, around 1973 at MIT, was enthralling. While Ailey’s work, which I was also enraptured by, struck me as heart and passion, Gus and his Cunningham-like vocabulary and odd organizing principles seemed to be a very different way of being Black. Its physicality was based on a subtle and ongoing interaction between body and mind, and an unapologetic assertion of the possibility that Blackness could be odd, astringent, and care little for respectability. I saw myself in him. And to some degree I still do.

Michael Blake, Faculty member, University of Missouri, Kansas City; former member of Paradigm

Puzzles. To work with Gus was a puzzle from the day you committed until the day you completed the task. He would give you a map in words or on paper and say, “Make steps!” I loved that! I loved hearing his voice say that, too! That map was confusing, complex, challenging, and in the end, beautiful to look at and perform. Gus challenged my brain as well as my body and my nervous system.

Courtney Escoyne, senior editor at Dance Magazine; former NYU Tisch student

Gus fundamentally altered the way I look at and talk about dance. Responding to our peers’ movement studies week to week always started in the same way: Gus projecting his warm, resonant voice to ask us, “Now, what did you see?” It was an invitation to not leap immediately to judgments of good or not good, whether what we’d seen was to our taste or not, and instead to analyze what had actually unfolded and what we had taken from it. The word ‘like’ was banned from the room. If we wanted to express appreciation, we had to specify if we were intrigued, moved, made curious. He encouraged us to do the same thing when we attended performances, and reliably listened to, questioned, and supported our conclusions about what did and didn’t work. When he offered his own observations, it was invariably with wit, wisdom, and kindness—and more often than not opened up new angles we hadn’t considered.

A decade later, every time I sit at a keyboard to write about a performance or draw breath to give feedback to a peer, it’s still his voice that I hear first, asking not whether I had liked it, but what I had seen.

¶¶Quotes from Gus’s lips or pen¶¶

¶ On Cunningham technique: “Since the dancing was not ‘about’ anything but the movement itself, absolute clarity was quintessential to its full expression, and you couldn’t mask a wobble with a dramatic flourish.” Dance Magazine, November 2007, “Technique: Move Your feet! Merce Cunningham Technique.”

¶ “In my early preteens… I was practicing a move I had seen Donald O’Connor do…and I flipped backwards off the couch and broke a window in our living room. I wasn’t hurt, but I was punished…because I was dancing!” (Source: Sharon Kinney’s documentary on the first “From the Horse’s Mouth” in 1998, now in posted on Facebook.)

¶ “Studying with Merce Cunningham, learning to dance from stillness, was giving me technical control rather than sheer muscle power, on which I’d been dancing until then.” (Source: Reinventing Dance in the 1960s: Everything Was Possible, ed. Sally Banes)

¶ “When I was in the world of Martha Graham, I was clinging to the world of Merce Cunningham.” (Source: “Choreography in Focus,” 2016)

¶ “I try to write reviews that are both engaging to the readers and instructive to the creators, while respecting the integrity of their efforts—however effective or not they turn out to be.” (Source: “Meet the Press” panel, Dance/NYC, 2012, quoted by me in “A Debate on Snark,” collected in Through the Eyes of a Dancer: Wendy Perron, Selected Writings)

¶ “Paradigm…has reconfirmed my original naive conviction that dance can be a life-long vocation. Age need not be a limitation; it is a resource of life experience and dance craft that enriches performance beyond technical virtuosity.” (Source: AlumWeb Open Door Archive)

¶ “I’m dancing on momentum now. You can do more on momentum than on muscles.” (Source: “Moving Joyfully and Carefully into Old Age,” New York Times, April 2, 2000)

¶ How to watch a Cunningham work: “The idea is to let the movement enter your consciousness without hierarchy and respond to it in that way. And then your experience, your culture, and your needs at the moment will create a hierarchy for you.” (Source: Mondays With Merce, #14, interviewed by Nancy Dalva)

¶ “As I got less depressed…I started involving my dancers more—my dancers’ input into the work—which became a much more fulfilling way to make work.” (Source: Mondays With Merce, #14)

¶ “Architecture and dancing are exactly the same. You design using all the same elements — time, space and structure — except that in dance, time is not fixed.” (Source: Cambridge Black History Project)

¶ About A Thin Frost, his first choreography for Paradigm: “It would change every [night]. Every time we’d come offstage, Carmen would say, ‘Well, who were we tonight? That never happened before!’” (Source: “From the Horse’s Mouth” Celebration of Gus Solomons, Interview with me, 2016, long version)

¶ Advice for making dances: “When I watch a dance I don’t want to be able to check out and do my emails. Keep me interested. Keep giving me new information. Take me on a journey. When I finish watching your piece, I want to be in a completely different place than when I started.” (Source: “From the Horse’s Mouth” Celebration of Gus Solomons, Interview with me, 2016, long version)

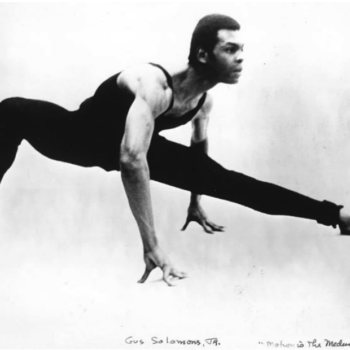

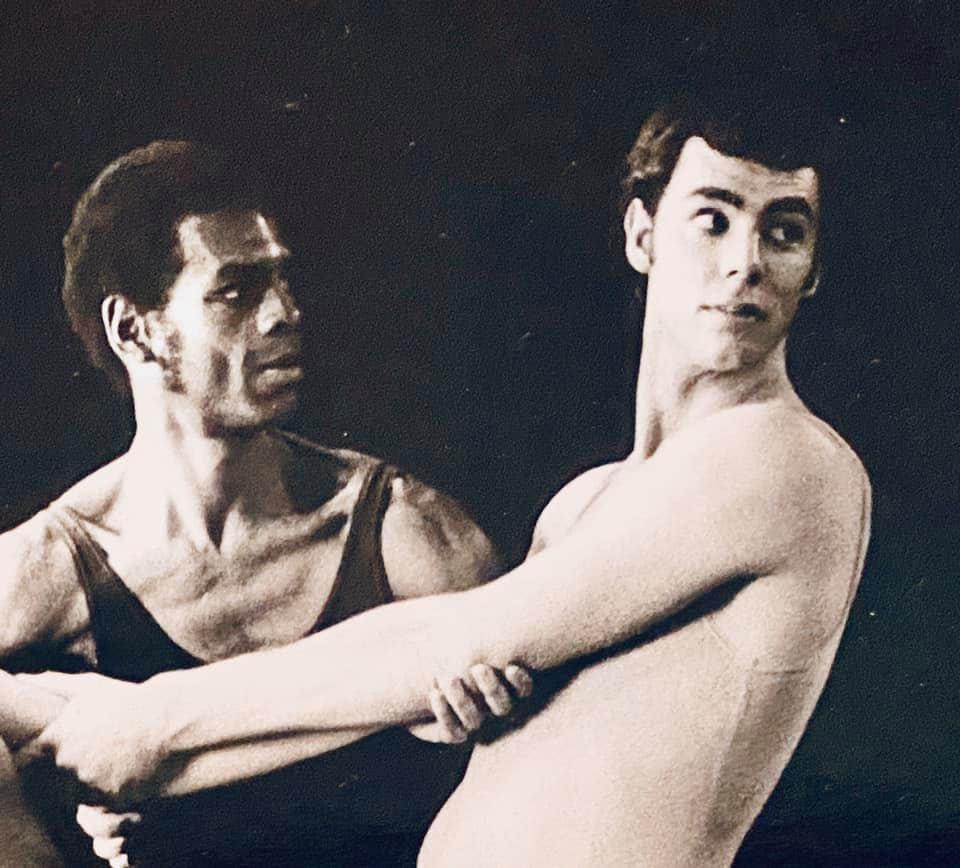

Photographed by MIT electrical engineering professor Harold Edgerton with stroboscopic camera, 1960.

The Gus Solomons Papers are held at the Jerome Robbins Dance Division of The New York Public Library for the Performing Arts.

Last(ing) memory: I visited Gus at Mt. Sinai Morningside Hospital on July 25. He looked vibrant to me, so I did not think this would be the last time I’d see him. When I was leaving, Gus (usually so unsentimental) took my hand and kissed it.

Featured 3